|

|

| Korean J Med > Volume 94(2); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease characterized by worsening lung function and dyspnea. The prognosis of IPF patients is poor, as median survival is approximately 3 years. However, recently developed IPF-specific therapies have shown improved efficacies in terms of reducing lung function decline and mortality. Therefore, the early recognition and accurate diagnosis of IPF are crucial. In 2018, new guidelines for the diagnosis of IPF were published by the Fleischner Society and by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Latin American Thoracic Society (ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT). Both guidelines emphasize the need for a thorough history taking and physical examination to exclude an alternative diagnosis, such as exposure-related or connective tissue disease. The most informative initial examination is high-resolution computed tomography, the results of which can indicate the need for bronchoalveolar lavage or surgical lung biopsy, based on a multidisciplinary discussion of the findings and the patientŌĆÖs clinical condition. A multidisciplinary discussion of the clinico-radiologic-pathologic findings is currently the gold standard in the diagnoisis of IPF and will allow the more effective and timely treatment of these patients.

Ļ░äņ¦łņä▒ ĒÅÉņ¦łĒÖś(interstitial lung disease, ILD)ņØĆ ĒÅÉņŗżņ¦łņØä ņ╣©ļ▓öĒĢśļŖö ļ╣äĻ░ÉņŚ╝ņä▒, ļ╣äņóģņ¢æņä▒ ņ¦łĒÖśņ£╝ļĪ£ņä£ ĒÅÉĒż ņé¼ņØ┤ Ļ│ĄĻ░äņØĖ Ļ░äņ¦ł(interstitium)ņŚÉ ņäĖĒżņØś ņ”ØņŗØĻ│╝ ļČäĒÖö, ļ¦īņä▒ņĀüņØĖ ņŚ╝ņ”Ø ļ░Å ņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖö ļō▒ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ļ│æļ”¼ ĻĖ░ņĀäņØ┤ ļö░ļĪ£ Ēś╣ņØĆ ļÅÖņŗ£ņŚÉ ļéśĒāĆļéśļŖö ņ¦łĒÖśĻĄ░ņØä ĒåĄņ╣ŁĒĢ£ļŗż[1]. ņØ┤ ņżæ Ļ░äņ¦łņØś ņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖöĻ░Ć Ļ░Ćņן ĒØöĒĢ£ Ēæ£ĒśäĒśĢ(phenotype)ņ£╝ļĪ£, ņØ┤ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ĒÅÉĒÖ£ļ¤ēņØś Ļ░Éņåī ļ░Å Ļ░ĆņŖż ĻĄÉĒÖśņØś ņןņĢĀļź╝ Ļ▓ĮĒŚśĒĢśļ®░ ņŗ¼ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ĒśĖĒØĪ ļČĆņĀä ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņØ┤ļź┤Ļ▓ī ļÉ£ļŗż. ņĢĮļ¼╝, ņ£ĀĻĖ░ Ēś╣ņØĆ ļ¼┤ĻĖ░ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļģĖņČ£, ļ░®ņé¼ņäĀ ņ╣śļŻī, Ļ▓░ņ▓┤ņĪ░ņ¦üņ¦łĒÖś ļō▒ ņ£Āļ░£ ņøÉņØĖņØä ņĢī ņłś ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ņ׳Ļ│Ā, ņ×ÉņäĖĒĢ£ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ļ░£ļ│æ ņøÉņØĖņØ┤ ļ░ØĒśĆņ¦Ćņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØä ļĢīļÅä ņ׳ļŖöļŹ░, ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļź╝ ĒŖ╣ļ░£ņä▒ Ļ░äņ¦łņä▒ ĒÅÉļĀ┤(idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, IIP)ņØ┤ļØ╝ ņ¦Ćņ╣ŁĒĢśļ®░ ĻĘĖņżæ Ļ░Ćņן ņśłĒøäĻ░Ć ļČłļ¤ēĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĒŖ╣ļ░£ņä▒ ĒÅÉņä¼ņ£Āņ”Ø(idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF)ņØ┤ļŗż[2]. IPFļŖö 65ņäĖ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļģĖņØĖņŚÉņä£ ĒśĖļ░£ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņłśĻ░£ņøöņŚÉņä£ ņłśļģäņŚÉ Ļ▒Ėņ│É ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢśļŖö ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│żļ×Ć, ļ¦łļźĖ ĻĖ░ņ╣© ļ░Å ņ▓Łņ¦äņŗ£ ņ¢æņĖĪ ĒÅÉĒĢśļČĆņØś ĒØĪĻĖ░ ņłśĒżņØīņØä ĒŖ╣ņ¦Ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢśļ®░, ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ņżæĻ░ä ņāØņĪ┤ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØĆ ņ¦äļŗ© Ēøä 3-5ļģäņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[3]. ĒØĪņŚ░ņØĆ IPFņØś ņל ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŖö ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉļĪ£, ĻĘĖ ļ░¢ņŚÉ ņ£ä-ņŗØļÅäņŚŁļźś, Epstein Barr virusļéś Hepatitis C virus ļō▒ņØś Ļ░ÉņŚ╝ ļ░Å ņ£ĀņĀäņ×É ļ│ĆņØ┤ ļō▒ļÅä ņ¦łļ│æ ļ░£ņāØĻ│╝ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż.

2000ļģä IPFņØś ņ¦äļŗ©Ļ│╝ ņ╣śļŻīņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░Ć ņØśĻ▓¼ņØä ĻĖ░ļ░śņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ ņ▓½ ĻĄŁņĀ£ ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ņØ┤Ēøä[4], ņ×äņāü ņ”Øņāü, ļ░£ļ│æ ĻĖ░ņĀä, ņ×ÉņŚ░ Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļōżņØä ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ 2011ļģäņŚÉ ņ¦äļŗ©Ļ│╝ ņ╣śļŻīņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ņżæņŗ¼(evidence-based)ņØś ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż[5]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØ┤Ēøä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņØś ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ņŗżņĀ£ ņ¦äļŻīņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņä£ņØś ņĀüņÜ®ņŚÉ ĒĢ£Ļ│äļź╝ ļ│┤ņ×äņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝[6,7], ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņØś IPFņØś ņ¦äļŗ© ĻĖ░ņżĆņØä ļ│┤ņÖäĒĢ£ ņāłļĪ£ņÜ┤ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ 2018ļģäņŚÉ ņä£ļĪ£ ļŗżļźĖ ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņŚÉņä£ ņĀ£ņŗ£ļÉśņŚłļŗż[3,8].

IPFņØś ļČłļ¤ēĒĢ£ ņśłĒøäļź╝ Ļ░ÉņĢłĒĢśļ®┤, ņ×äņāü ņØśņé¼Ļ░Ć ņĪ░ĻĖ░ņŚÉ ņĀĢĒÖĢĒĢ£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ļé┤ļ”¼ļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ IPF ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņśłĒøäņŚÉ ļ¦żņÜ░ ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ļŹ░, ņØ┤ļŖö pirfenidone [7], nintedanib [9]Ļ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņ¦łļ│æ ņ¦äĒ¢ē ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņŚÉ ņ£ĀĒÜ©ĒĢ£ ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØś Ļ░£ļ░£ļĪ£ ĻĘĖ ņżæņÜöņä▒ņØ┤ ļŹöņÜ▒ Ļ░ĢņĪ░ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļ│Ė ņóģņäżņØĆ ņāłļĪ£ņÜ┤ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ IPFņØś ņ¦äļŗ© Ļ│╝ņĀĢņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢśĻ│Āņ×É ĒĢ£ļŗż.

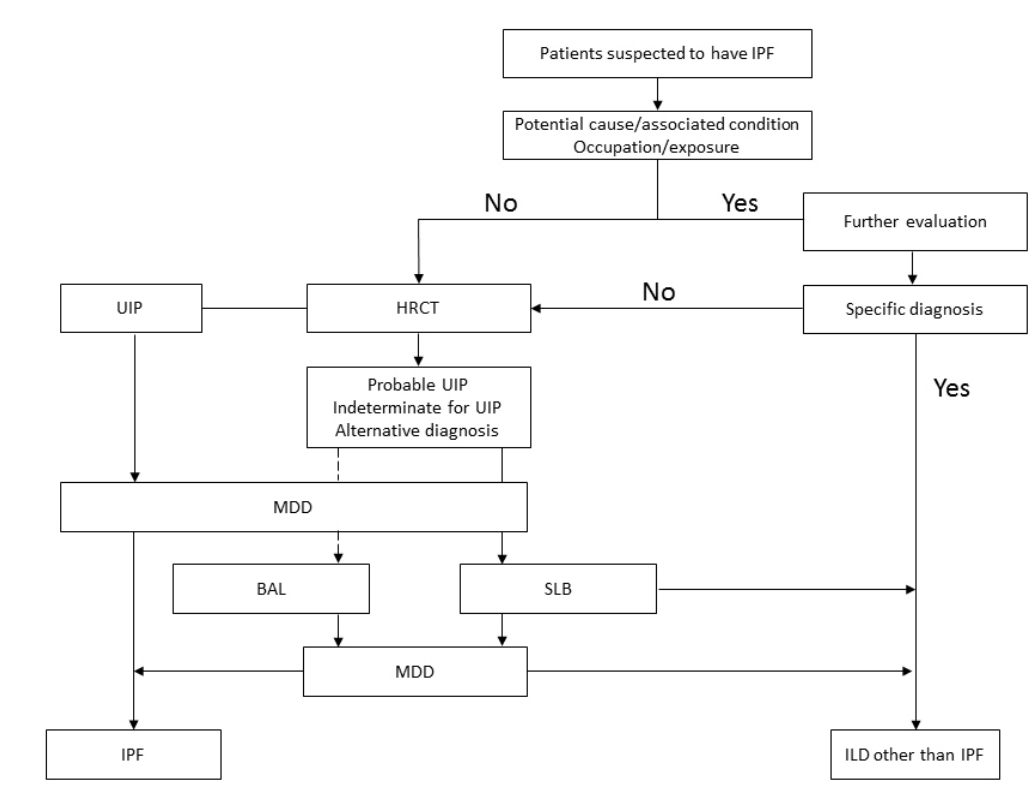

IPFĻ░Ć ņØśņŗ¼ļÉśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļ│æļĀź ņ▓ŁņĘ©ņÖĆ ņØ┤ĒĢÖņĀü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦üņŚģņä▒ ĒÅÉņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ļéś Ļ▓░ņ▓┤ņĪ░ņ¦üņ¦łĒÖś ļō▒ ņøÉņØĖ Ļ░Éļ│äņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņ¦łĒÖś ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ ĒīÉļŗ©ĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ│ĀĒĢ┤ņāüļÅä ĒØēļČĆ ņĀäņé░ĒÖöļŗ©ņĖĄņ┤¼ņśü(high resolution computed tomography, HRCT)ņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ┤Ēøä ļŗżĒĢÖņĀ£ ĒåĀļĪĀ(multidisciplinary discussion, MDD)ņØä ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦ĆĒÅÉĒżņäĖņ▓Ö Ļ▓Ćņé¼(bronchoalveolar lavage, BAL)ļéś ņÖĖĻ│╝ņĀü ĒÅÉņāØĻ▓Ć(surgical lung biopsy, SLB) ļō▒ņØś ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ£ļŗż. ĒŖ╣ņ¦ĢņĀüņØĖ IPFņØś HRCT ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░(ĒåĄņāüĒśĢ Ļ░äņ¦łņä▒ ĒÅÉļĀ┤[usual interstitial pneumonia, UIP]ĒśĢ)ļŖö ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņŚåņØ┤ļÅä IPFļź╝ ņ¦äļŗ©ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļéś, ĻĘĖļĀćņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ļō▒ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ Ēøä ļŗżņŗ£ MDDļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĄ£ņóģņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ IPF ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉ£ļŗż(Fig. 1).

Ļ│ĀļĀ╣ņ×É(ĒŖ╣Ē׳ 60ņäĖ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļé©ņ×É)Ļ░Ć 6Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ņāü ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉśļŖö ĒśĖĒØĪĻ│żļ×ĆņØ┤ļéś ļ¦łļźĖ ĻĖ░ņ╣©ņØä ĒśĖņåīĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņŗĀņ▓┤ ņ¦äņ░░ņŚÉņä£ Ļ│żļ┤ēņ¦Ć(clubbing) Ēś╣ņØĆ ĒØĪĻĖ░ņŗ£ ņłśĒżņØīņØ┤ ļōżļ”¼Ļ▒░ļéś, ĒØēļČĆ X-rayņŚÉņä£ ņ¢æĒÅÉĒĢśļČĆņØś ņ”ØĻ░ĆļÉ£ ņØīņśüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ IPFļź╝ ņØśņŗ¼ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļéśņØ┤Ļ░Ć 40-60ņäĖļĪ£ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņĀŖņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļÅä ĒÅÉņä¼ņ£Āņ”ØņØś Ļ░ĆņĪ▒ļĀźņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗżļ®┤ IPFņØś Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņØä ņŚ╝ļæÉņŚÉ ļæÉĻ│Ā ņ×ÉņäĖĒĢ£ ļ│æļĀź ņ▓ŁņĘ©Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ĒØĪņŚ░ļĀźĻ│╝ ņ¦üņŚģņä▒ ĒÅÉņ¦łĒÖśņØś ļ░░ņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦üņŚģļĀźņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņ×ÉņäĖĒĢ£ ļ¼Ėņ¦äņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśĻ│Ā, Ļ│╝ļ»╝ņä▒ĒÅÉņןņŚ╝ ļō▒ņØś Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ│┤(Ļ▒░ņŻ╝ĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ĻĘ╝ļ¼┤ĒĢśļŖö Ļ││ņŚÉņä£ Ļ│░ĒīĪņØ┤ļéś ņāłņÖĆ ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ņĀæņ┤ēĒĢśņśĆļŖöņ¦Ć ļō▒)ļź╝ ņ¢╗ņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØ┤ļéś ļ░®ņé¼ņäĀ ņ╣śļŻī ņŚ¼ļČĆ ļō▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļÅä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ▓░ņ▓┤ņĪ░ņ¦üņ¦łĒÖś(connective tissue disease)ņØś ļÅÖļ░ś Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ┤ĆņĀł ļ░Å Ēö╝ļČĆ ļō▒ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņ”ØņāüņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ│æļĀź ņ▓ŁņĘ©Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśĻ│Ā, Ļ┤ĆņĀł ļō▒ ĒÅÉ ņÖĖ ņ”Øņāü ņŚåņØ┤ ILDĻ░Ć ņäĀĒ¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£ ļ¼┤ņ”ØņāüņØ┤ļØ╝ļÅä ĒĢŁĒĢĄĒĢŁņ▓┤(antinuclear antibody)ļéś ļźśļ¦łĒŗ░ņŖż ņØĖņ×É(rheumatoid factor) ļō▒ ņ×ÉĻ░ĆĒĢŁņ▓┤ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ļŗż[3].

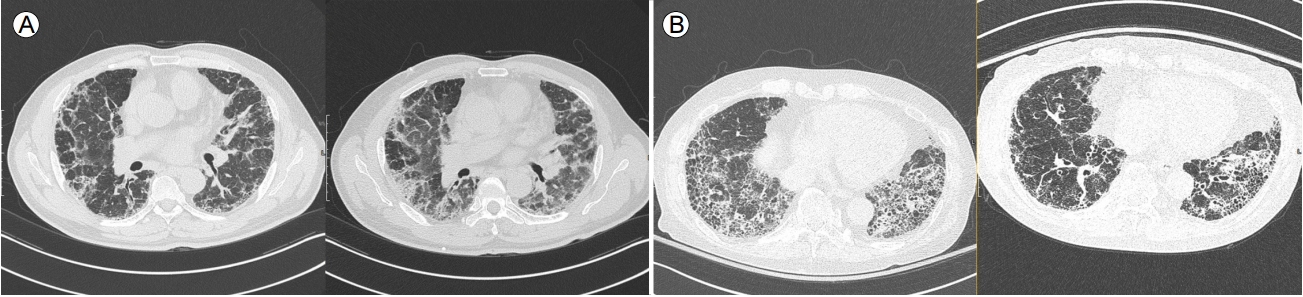

HRCTļŖö 2 mm ņØ┤ĒĢśņØś ņ¢ćņØĆ ļæÉĻ╗ś(thickeness)ļź╝ Ļ░¢ļŖö ņśüņāüņØä 1-2 cm Ļ░äĻ▓®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ┤¼ņśüĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÅÉņŗżņ¦łņØś ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ļ»╝Ļ░ÉĒĢśĻ▓ī ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö CT ņ┤¼ņśüĻĖ░ļ▓ĢņØ┤ļŗż[10]. Ļ│ĄĻĖ░Ļ▒Ėļ”╝(air trapping)ņØ┤ļéś ĒÅÉĒŚłĒāł(atelectasis) ļō▒ņØś ļÅÖļ░ś ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒØĪĻĖ░ ļ¦É ņśüņāü ņÖĖņŚÉ ĒśĖĻĖ░ ļ¦ÉĻ│╝ ļ│ĄņÖĆņ£ä ņ×ÉņäĖ(prone position)ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņ┤¼ņśüĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ļŗżļźĖ ILDļéś Ļ░Ćņä▒ļ│æņåī(pseudolesion) Ļ░Éļ│äņŚÉ ļÅäņøĆņØ┤ ļÉ£ļŗż[3] (Fig. 2).

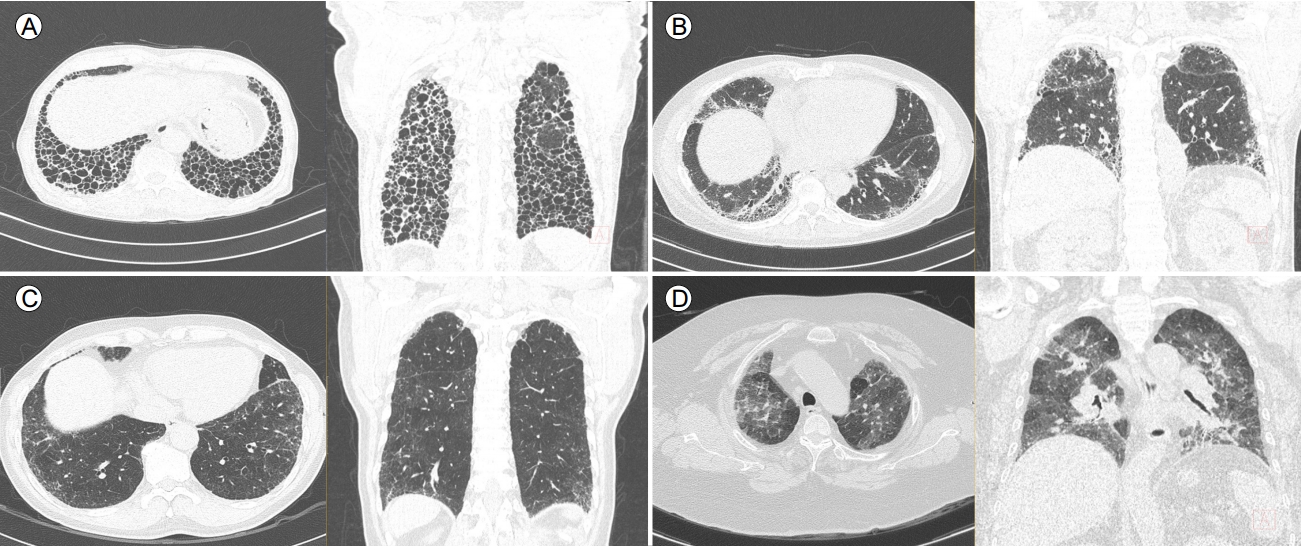

2011ļģäņŚÉ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ IPF ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņ▓ĀņĀĆĒĢ£ ļ│æļĀź ņ▓ŁņĘ©, ņ×ÉĻ░ĆĒĢŁņ▓┤ ļō▒ņØś Ļ▓Ćņé¼ņŚÉņä£ ņøÉņØĖņØ┤ ļ░ØĒśĆņ¦Ćņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ IIP ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ HRCTļź╝ ļ©╝ņĀĆ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ĻĘĖ ņåīĻ▓¼ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ 3Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņ£ĀĒśĢ(UIP pattern, possible UIP pattern, inconsistent UIP pattern)ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢśņŚ¼, UIP patternņØĖ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļź╝ ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢśĻ│ĀļŖö SLBļź╝ ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż[5]. HRCT ņāü ĒÅÉĒĢśļČĆ, ļ│ĆņŚ░ļČĆ ņÜ░ņäĖņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ┤ēņÖĆņ¢æĒÅÉ(honeycombing)ņÖĆ ļ¦ØņāüņØīņśü(reticular abnormality)ņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļŗżļźĖ ņ¦łĒÖśņØä ņŗ£ņé¼ĒĢśļŖö ņåīĻ▓¼(ņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖö ļ│æļ│Ćļ│┤ļŗż ļ▓öņ£äĻ░Ć ļŹö ļäōņØĆ Ļ░äņ£Āļ”¼ņØīņśü[ground glass opacity], ĒÅÉĻ▓ĮĻ▓░[consolidation], ņżæ-ņāüņŚĮ ņ╣©ļ▓ö ļō▒)ņØ┤ ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ņśüņāüņØśĒĢÖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ UIP patternņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ│æļ”¼ ņåīĻ▓¼ņāü UIP patternĻ│╝ ņØ╝ņ╣śļÅäĻ░Ć ļ¦żņÜ░ ļåÆņØĆ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłļŗż[11]. ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņØś ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĢ×ņä£ņé┤ĒÄ┤ļ│Ė UIP patternņØś 4Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ĒŖ╣ņ¦Ģ(ĒÅÉĒĢśļČĆ/ļ│ĆņŚ░ļČĆ ņÜ░ņäĖņä▒, ļ┤ēņÖĆņ¢æĒÅÉ, ļ¦ØņāüņØīņśü, ļŗżļźĖ ņ¦łĒÖśņØä ņŗ£ņé¼ĒĢśļŖö ņåīĻ▓¼ņØ┤ ņŚåņØī) ņżæ ļ┤ēņÖĆņ¢æĒÅÉļź╝ ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ ļéśļ©Ėņ¦Ć 3Ļ░Ćņ¦Ćļź╝ ļ¦īņĪ▒ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļź╝ possible UIP patternņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀĢņØśĒĢśņśĆļŖöļŹ░, Chung ļō▒[12]ņØĆ possible UIP patternņØä ņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖöņØś ņĀĢļÅäļĪ£ ļéśļłäņ¢┤ probable UIP (ĒÅÉĒĢśļČĆ, ļ│ĆņŚ░ļČĆ ņÜ░ņäĖņä▒, ļ¦ØņāüņØīņśü ņĪ┤ņ×¼, ļŗżļźĖ ņ¦łĒÖśņØä ņŗ£ņé¼ĒĢśļŖö ņåīĻ▓¼ņØ┤ ņŚåņØī)ņÖĆ indeterminate UIP pattern (CT ņāü ĒÅÉņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖöĻ░Ć ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļéś definite, probable Ēś╣ņØĆ inconsistent with UIPļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢĀ ņĀĢļÅäļĪ£ ĒŖ╣ņ¦ĢņĀüņØ┤ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░)ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśļłäņ¢┤ ļ│æļ”¼ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, probable UIP patternņŚÉņä£ ļ│æļ”¼ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ņāü UIP patternņØ┤ ļŹö ņ×ÉņŻ╝ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ļÉ©ņØä ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż(82.4% vs. 54.2%; p= 0.01). ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ 2018ļģä Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒØēļČĆ HRCT ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä UIP, probable UIP, indeterminate for UIP, alternative diagnosisņØś 4Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Table 1, Fig. 3) [3,8].

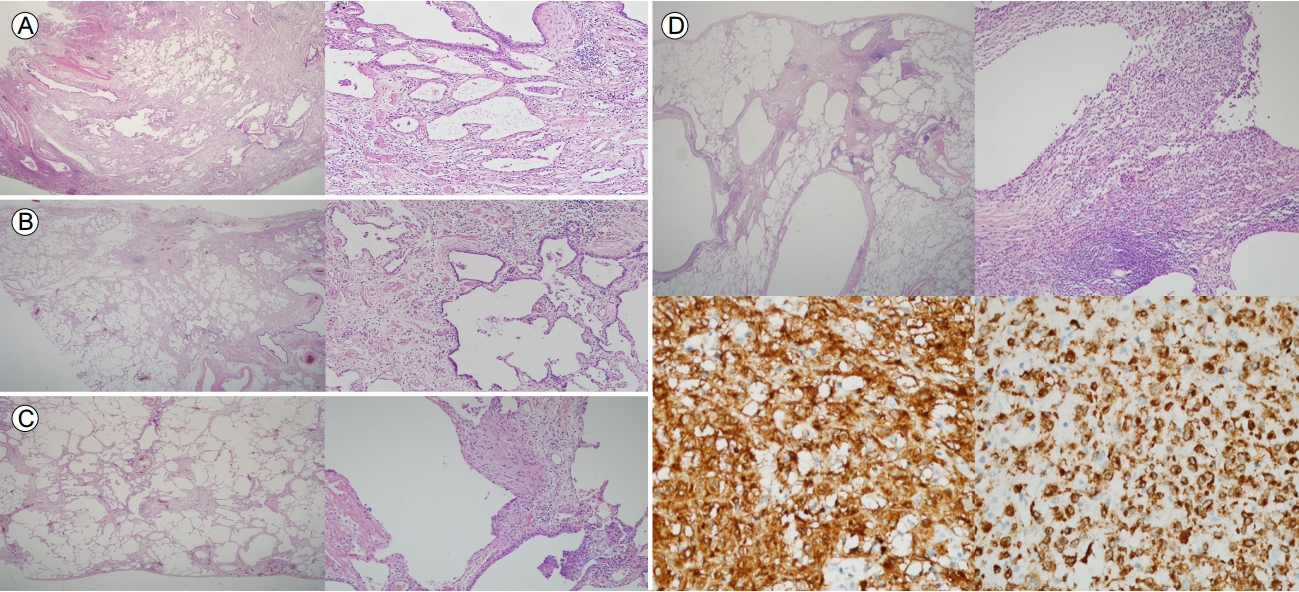

2018ļģä Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉ ļö░ļź┤ļ®┤ ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņåīĻ▓¼ļÅä ņśüņāüĻ│╝ ļ¦łņ░¼Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļĪ£ UIP, probable UIP, indeterminate for UIP, alternative diagnosisņØś 4Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Table 2, Fig. 4). Ļ░ÖņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņä£ļĪ£ ļŗżļźĖ ļæÉ ņŚĮņŚÉņä£ ļŗżļźĖ ņĪ░ņ¦üĒśĢņØ┤ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ(discordant UIP; ņ”ē ĒĢ£ ņŚĮņŚÉņä£ļŖö UIP pattern, ļŗżļźĖ ņŚĮņŚÉņä£ļŖö nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern), SLB ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŗ£ ņĄ£ņåī 2Ļ││ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ĒÅÉņŚĮņŚÉņä£ ņĪ░ņ¦üņØä ņ¢╗ņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[3].

ĒÅÉņāØĻ▓Ć Ēøä ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”Øņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ĻĖēņä▒ņĢģĒÖö(6.1%), ņ¦ĆņåŹņĀüņØĖ Ļ│ĄĻĖ░ ļłäņČ£(6-12%), Ļ░ÉņŚ╝(6.5%), ņČ£Ēśł(0.2-0.8%) ļō▒ņØ┤ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[13]. Hutchinson ļō▒[14]ņØĆ 11ļģäĻ░ä 32,022ļ¬ģņØś SLBļź╝ ļ░øņØĆ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ļ¦ØĻ│╝ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ņØĖņ×Éļź╝ ļČäņäØĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā ļé©ņ×É, Ļ│ĀļĀ╣, ĻĖ░ņĀĆ ņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ ļ¦ÄņØäņłśļĪØ ņé¼ļ¦ØņØ┤ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢ©ņØä ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ 75ņäĖ ņØ┤ņāüņØĆ 45ņäĖ ļ»Ėļ¦īņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ 4.5ļ░░ ņé¼ļ¦Ø ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļśÉ ņĢłņĀĢņŗ£ Ēś╣ņØĆ ņÜ┤ļÅÖņŗ£ ņé░ņåīļź╝ ĒĢäņÜöļĪ£ ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņé¼ļ¦Ø, ĒÅÉļĀ┤, ņ¦ĆņåŹņĀüņØĖ Ļ│ĄĻĖ░ ļłäņČ£ ļō▒ņØś ņŻ╝ņÜö ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”ØņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ĒÖĢļźĀņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢ£ļŗż. LoCicero [15]ņØś ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ĒÅÉņāØĻ▓Ćņŗ£ ņé░ņåī ņÜöĻĄ¼ļ¤ēņØ┤ ņŚåņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØĆ 4%, ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņé░ņåīĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö 6% ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā ĒśĖĒØĪļČĆņĀäņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻĖ░Ļ│ä ĒÖśĻĖ░Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö 75%ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ĒĢĀ ļŗ╣ņŗ£ ĻĖēņä▒ņĢģĒÖöņØś ļ│æļĀźļÅä ņĢīļĀżņ¦ä ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉļĪ£ņä£, Park ļō▒[16]ņØĆ SLBļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļ░øņØĆ 200ļ¬ģņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ĻĖēņä▒ņĢģĒÖöņŗ£ ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ļ░øņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀ(28.6%)ņØ┤ ĻĘĖļĀćņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░(3.0%)ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśĻ│Ā, ĒÅÉĒÖĢņé░ļŖź(diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide)ņØ┤ ļé«ņØäņłśļĪØ ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ Ēøä ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”ØņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØī(odds ratio, 0.959; 95% confidence interval, 0.930-0.989; p= 0.007)ņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż. ĻĘĖ ņÖĖņŚÉ Ļ│ĀļĀ╣, ļ®┤ņŚŁņĀĆĒĢś ņāüĒā£, ņżæņ”ØņØś ĒÅÉĻ│ĀĒśłņĢĢņØ┤ ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŻ╝ņØśĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[15,17-19].

2011ļģä ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ SLBņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ ļ╣äļööņśż ĒØēĻ░ĢĻ▓Į ņłśņłĀ(video assisted thoracic surgery, VATS)Ļ│╝ Ļ░£ĒØēņłĀ(open lung thoracotomy, OLB)ņØä Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņłśņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ņåīĻ░£ĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļéś, Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö VATSļź╝ ņČöņ▓£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. 41ļ¬ģņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ VATSņÖĆ OLBņØś ĒÜ©ņÜ®ņä▒ņØä ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£, VATS ņŗ£Ē¢ēņŗ£ ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£Ļ░ä(45.3 ┬▒ 12.2ļČä vs. 55.6 ┬▒ 11.2ļČä)Ļ│╝ ņ×ģņøÉ ĻĖ░Ļ░ä(5.5 ┬▒ 1.3ņØ╝ vs. 7.1 ┬▒ 2.3ņØ╝)ņØ┤ OLBņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņżäņ¢┤ļōżņŚłņØīņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłĻ│Ā[20], ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀļÅä ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ļé«ņĢśļŗż(1.18% vs. 2.29%, p< 0.001) [14].

ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦Ć ļé┤ņŗ£Ļ▓ĮņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ļāēļÅÖĒÅÉņāØĻ▓Ć(bronchoscopic lung cryobiopsy) ņŗ£ņłĀņØ┤ ILDņØś ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ļ░®ļ▓Ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£ļÅäļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[21,22]. 117ļ¬ģņØś ILD ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļāēļÅÖĒÅÉņāØĻ▓ĆĻ│╝ VATSļź╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£, ņĪ░ņ¦üņØś ņĀüĒĢ®ņä▒(100% vs. 100%)ņØ┤ļéś ILDņØś ņ¦äļŗ©ņ£©(91% vs. 98%, p= 0.71) ļ░Å ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀ(1.7% vs. 3.4%)ņØ┤ ļæÉ ļ░®ļ▓Ģ Ļ░ä ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłļŗż[22]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī Ļ░ü ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćļ│äļĪ£ ņłÖļĀ©ļÅäĻ░Ć ļŗżļź┤Ļ│Ā, ņŗ£ņłĀ Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØ┤ Ēæ£ņżĆĒÖöļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĢäņ¦ü ILDļź╝ ņ¦äļŗ©ĒĢśļŖö ļ░®ļ▓Ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż[3].

2011 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS)/Latin American Thoracic Society (ALAT) ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©Ļ│╝ ļÅÖņØ╝ĒĢśĻ▓ī 2018ļģä ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļÅä HRCT ņāü ņĀäĒśĢņĀüņØĖ UIPĒśĢņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö SLBļź╝ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś 2011ļģä ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ņØ┤Ēøä HRCTņÖĆ ņĪ░ņ¦ü ņåīĻ▓¼ņØś ņØ╝ņ╣śņ£©ņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņØ┤ ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā, ĒØēļČĆ HRCT ņāü ļ┤ēņÖĆņ¢æĒÅÉĻ░Ć ņŚåļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ĒØēļ¦ēĒĢśņŚÉ ļ¦ØņāüņØīņśüĻ│╝ Ļ▓¼ņØĖņä▒ ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦ĆĒÖĢņןņ”ØņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ņŚÉņä£ UIPĻ░Ć ņ¦äļŗ©ļÉĀ ĒÖĢļźĀņØ┤ ļåÆņØī(82-94%)ņØ┤ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż[11,12]. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ 60ņäĖ ņØ┤ņāü ļé©ņ×É, ĒØĪņŚ░ļĀź ļō▒ņØś ņ×äņāüņ¢æņāüņØä ļ¦īņĪ▒ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ņØ╝ņ╣śļÅäĻ░Ć ļŹö ļåÆņĢäņ¦ÉņØä ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ļĪ£[23], 2018ļģä Fleishner ĻĘĖļŻ╣ņŚÉņä£ļŖö IPFņØś ņ×äņāüņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ĒØēļČĆ CT ņāü probable UIPĒśĢņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ SLB ņŚåņØ┤ļÅä IPFļź╝ ņ¦äļŗ©ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżĻ│Ā ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż[8]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØ┤ņ¢┤ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ 2018ļģä ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒØēļČĆ CT Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņāü probable UIP ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ SLBļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīņ£ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż(conditional recommendation) [3]. ļ╣äļĪØ Ēæ£ļ®┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ĒØēļČĆ CT ņāü probable UIP ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ ļæÉ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØś Ļ▓¼ĒĢ┤Ļ░Ć ļŗżļźĖ Ļ▓āņ▓śļ¤╝ ļ│┤ņØ┤ņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ conditional recommendationņ£╝ļĪ£ņä£, HRCTņŚÉņä£ probable UIP ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ļŗżņłś(Ōēź 50%)ļŖö SLBĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØ╝ļČĆ(<50%) ĒÖśņ×É(ņśłļź╝ ļōżļ®┤ ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ IPFņØ╝ Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ)ņŚÉņä£ļŖö SLBĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØä ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļØ╝Ļ│Ā ĒĢ┤ņäØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņŚÉņä£ ļæÉ ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ņØśļÅäĒĢśļŖö ļ░öļŖö ļÅÖņØ╝ĒĢśļŗżĻ│Ā ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[24,25].

ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦ĆĒÅÉĒżņäĖņ▓Ö Ļ▓Ćņé¼(BAL)ļŖö ĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦Ć ļé┤ņŗ£Ļ▓ĮņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĖ░ļÅäļé┤ ņ┤Ø 100-300 mLņØś ņāØļ”¼ņŗØņŚ╝ņłśļź╝ 3-5ĒÜī ļéśļłäņ¢┤ ņŻ╝ņ×ģ Ēøä ĒÜīņłśĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ¦Éņ┤ł ĻĖ░ļÅäņÖĆ ĒÅÉĒżņŚÉņä£ Ļ▓Ćņ▓┤ļź╝ ņ¢╗ļŖö Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ļŗż[26]. ĒÜīņłśļÉ£ ņäĖņ▓ÖņĢĪņØĆ ņŻ╝ņ×ģļÉ£ ņ¢æņØś ņĄ£ņåī 30% ņØ┤ņāüņØ┤ ļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ĻĘĖ ņØ┤ĒĢśņØ╝ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņäĖĒż ļČäņ£©(differential counts)ņØä ĒĢ┤ņäØĒĢśļŖöļŹ░ ņŻ╝ņØśĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

IPFņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ BAL ņäĖņ▓ÖņĢĪ ņåīĻ▓¼ņØĆ ņĀĢņāüņØĖ Ēś╣ņØĆ ļŗżļźĖ ĒÅÉņ¦łĒÖśņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒśĖņżæĻĄ¼ņØś ļ╣äņ£©ņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, Ļ▓░ņ▓┤ņĪ░ņ¦üĻ┤ĆļĀ© ĒÅÉņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ļéś ļŗżļźĖ ņ¦łĒÖśņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢ£ ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ│┤ņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ņ¢┤, 2011ļģä ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö IPF ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ BALņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż[5]. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś IPFĻ░Ć ņĢäļŗī ļŗżļźĖ ņ¦łĒÖśņØä Ļ░Éļ│äĒĢśļŖöļŹ░ ļÅäņøĆņØ┤ ļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖöļŹ░, BAL ņäĖĒżļČäĒÜŹņŚÉņä£ ĒśĖņé░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć 25% ņØ┤ņāüņØ┤ļ®┤ ĒśĖņé░ĻĄ¼ņä▒ ĒÅÉļĀ┤(eosinophilic pneumonia)ņŚÉ ņ¦äļŗ©ņĀüņØ┤Ļ│Ā[26], ņ£Āņ£Īņóģņ”Ø(sarcoidosis)ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ│┤ĒåĄ ļ”╝ĒöäĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć 15% ņØ┤ņāüņØ┤Ļ│Ā CD4/CD8 ļ╣äņ£©ņØ┤ 4 ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåÆļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ĒØēļČĆ CTņŚÉņä£ UIP patternņØ┤ ņĢäļŗī Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņāüĻĖ░ ņ¦łĒÖś ļō▒ņØä Ļ░Éļ│äĒĢĀ ļ¬®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ BAL ņäĖĒżļČäĒÜŹĻ│╝ CD4/CD8 ļ╣äņ£©ņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīĻ│Ā ņé¼ĒĢŁņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāłļĪŁĻ▓ī ņČöĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ļÉśņŚłļŗż[3].

IPF ņ¦äļŗ©ņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņØĆ ļŗżĒĢÖņĀ£ ĒåĀļĪĀņØä ĒåĄĒĢ£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ļŗż[3]. Flaherty ļō▒[27]ņØĆ IIPņØś ņ¦äļŗ© Ļ│╝ņĀĢņŚÉņä£ ņ×äņāü, ļ│æļ”¼, ņśüņāü ņĀĢļ│┤ņØś ĒåĄĒĢ®Ļ│╝ Ļ░ü ļČäņĢ╝ ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░Ć Ļ░ä ĒåĀļĪĀņØä ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØś ņØ╝ņ╣śļÅä(interobserver agreement)ņÖĆ ņŗĀļó░ļÅäļź╝ ļåÆņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ņØīņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż. Chaudhuri ļō▒[28]ņØĆ ņ¦ĆņŚŁ ļ│æņøÉņØś ĒśĖĒØĪĻĖ░ ņĀäļ¼ĖņØśļĪ£ļČĆĒä░ MDDļź╝ ņØśļó░ļ░øņØĆ 318ļ¬ģņØś ILD ņ”ØļĪĆļź╝ ļČäņäØĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£, ņĄ£ņ┤ł ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ IPFņśĆļŹś 107ļ¬ģ ņżæ ņĀłļ░śņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ MDD Ēøä ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, IPFļź╝ ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ ļŗżļźĖ ILD ĒÖśņ×É 136ļ¬ģļÅä 33%ņŚÉņä£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮļÉśņŚłņØīņØä ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. Jo ļō▒[29]ļÅä ĒśĖĒØĪĻĖ░ ņĀäļ¼ĖņØśļĪ£ļČĆĒä░ ņØśļó░ļ░øņØĆ 90ļ¬ģņØś ILD ĒÖśņ×É ņżæ MDDļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ 53%ņŚÉņä£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØ┤ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā, ņ╣śļŻī ļ░®ņ╣©ņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņä£ļÅä ĒĢŁņä¼ņ£ĀĒÖöņĀ£ņØś ņé¼ņÜ®(3% vs. 21%, p< 0.01)ņØ┤ļéś ņé░ņåī ņ╣śļŻī(6% vs. 10%, p= 0.046) ļō▒ņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ£ ļ│ĆĒÖöĻ░Ć ņ׳ņØīņØä ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļōżņØĆ MDDĻ░Ć ņ×äņāü ņ¦äļŻīņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņä£, ņ¦äļŗ©ļ┐Éļ¦ī ņĢäļŗłļØ╝ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņ╣śļŻī ļ░®ņ╣©ņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśĻ│Ā ņśłĒøäļź╝ ĒīÉļŗ©ĒĢśļŖö ļŹ░ņŚÉļÅä ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ņżīņØä ņŗ£ņé¼ĒĢ┤ ņżĆļŗż.

2018ļģä Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö MDDņØś ņżæņÜöņä▒ņØä ļŹöņÜ▒ Ļ░ĢņĪ░ĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒØēļČĆ HRCT ņĀĢļ│┤ļź╝ ņ¢╗ņØĆ Ēøä MDDļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņŚ¼ BALņØ┤ļéś SLB ļō▒ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņāüĻĖ░ Ļ▓Ćņé¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļōżņØä ĒåĀļīĆļĪ£ ļŗżņŗ£ ĒĢ£ļ▓ł MDDļź╝ ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīņ£ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Fig. 1). ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņĀäĒśĢņĀüņØĖ IPFņØś ņ×äņāü-ņśüņāüņāüņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ MDDĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśņ¦ĆļŖö ņĢŖļŗż[3]. Fleischner ĻĘĖļŻ╣ļÅä ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś, ņĪ░ņ¦ü Ļ▓Ćņé¼ Ēøä ņ×äņāü/ņśüņāü/ļ│æļ”¼ ņåīĻ▓¼ņØä ļ”¼ļĘ░ĒĢĀ ļĢī, ņ¦łļ│æņØś Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝Ļ░Ć ņĢīļĀżņ¦ä Ļ▓āĻ│╝ ļŗ¼ļØ╝ ņ×¼ĒÅēĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉ MDDļź╝ ņČöņ▓£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż[8]. MDDņØś ĻĄ¼ņä▒ņØĆ Ļ▓ĮĒŚśņØ┤ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņ×äņāü, ņśüņāü, ļ│æļ”¼ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░Ćļź╝ ĻĖ░ļ│Ėņ£╝ļĪ£, ĒĢäņÜöņŗ£ ĒÖśĻ▓Į, ņ£ĀņĀä, ļźśļ¦łĒŗ░ņŖżņ¦łĒÖś ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ņ░ĖņŚ¼ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīĻ│ĀļÉ£ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņ░ĖņŚ¼ ņØĖņøÉņØä ņ¢┤ļ¢╗Ļ▓ī ĻĄ¼ņä▒ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØĖņ¦Ć, ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā MDD ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŻ╝ĻĖ░ ļō▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ▓░ņĀĢņØĆ Ļ░ü ņä╝Ēä░ņØś ņ¦äļŻī ņŚ¼Ļ▒┤ņŚÉ ļ¦×Ļ▓ī ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż.

IPFļŖö ņ¦äļŗ© Ēøä ņ¦ĆņåŹņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢśņŚ¼ ļåÆņØĆ ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö ņ¦łĒÖśņ£╝ļĪ£, IPFĻ░Ć ņØśņŗ¼ļÉśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ļ░£Ļ▓¼Ļ│╝ ņĀĢĒÖĢĒĢ£ ņ¦äļŗ© ļ░Å ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņ╣śļŻīĻ░Ć ļ¦żņÜ░ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. Ļ░£ņĀĢļÉ£ IPF ņ¦äļŗ© ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ĒØēļČĆ HRCT ņåīĻ▓¼ņāü UIPĒśĢņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņÖĖņŚÉļÅä, ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ IPFĻ░Ć ņØśņŗ¼ļÉśļŖö ĒÖśņ×É(working diagnosis of IPF)ņŚÉņä£ SLB ņŚåņØ┤ļÅä IPFļź╝ ņ¦äļŗ©ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņŚ¼ņ¦Ćļź╝ ļæÉņŚłļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņØśņé¼Ļ▓░ņĀĢņØĆ MDDļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ņØ┤ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ╣©ņŖĄņĀü ņ¦äļŗ© ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ņäĀļ│äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļČłĒĢäņÜöĒĢśĻ▓ī ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņłśņłĀ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”ØņØä ņżäņØ┤Ļ│Ā ņĀĢĒÖĢĒĢ£ ņ¦äļŗ©ņØä ļé┤ļ”¼ļŖöļŹ░ ĻĖ░ņŚ¼ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņśłņāüĒĢ£ļŗż.

REFERENCES

2. Barratt SL, Creamer A, Hayton C, Chaudhuri N. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): an overview. J Clin Med 2018;7:E201.

3. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198:e44ŌĆōe68.

4. American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment: International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:646ŌĆō664.

5. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788ŌĆō824.

6. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network, Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1968ŌĆō1977.

7. King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2083ŌĆō2092.

8. Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:138ŌĆō153.

9. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2071ŌĆō2082.

10. Mayo JR. CT evaluation of diffuse infiltrative lung disease: dose considerations and optimal technique. J Thorac Imaging 2009;24:252ŌĆō259.

11. Raghu G, Lynch D, Godwin JD, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with high-resolution CT in patients with little or no radiological evidence of honeycombing: secondary analysis of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:277ŌĆō284.

12. Chung JH, Chawla A, Peljto AL, et al. CT scan findings of probable usual interstitial pneumonitis have a high predictive value for histologic usual interstitial pneumonitis. Chest 2015;147:450ŌĆō459.

13. Kaarteenaho R. The current position of surgical lung biopsy in the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2013;14:43.

14. Hutchinson JP, Fogarty AW, McKeever TM, Hubbard RB. In-hospital mortality after surgical lung biopsy for interstitial lung disease in the United States. 2000 to 2011. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:1161ŌĆō1167.

15. LoCicero J 3rd. Does every patient with enigmatic lung disease deserve a lung biopsy? The continuing dilemma. Chest 1994;106:706ŌĆō708.

16. Park JH, Kim DK, Kim DS, et al. Mortality and risk factors for surgical lung biopsy in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:1115ŌĆō1119.

17. Raj R, Raparia K, Lynch DA, Brown KK. Surgical lung biopsy for interstitial lung diseases. Chest 2017;151:1131ŌĆō1140.

18. Kayatta MO, Ahmed S, Hammel JA, et al. Surgical biopsy of suspected interstitial lung disease is superior to radiographic diagnosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:399ŌĆō401.

19. Kreider ME, Hansen-Flaschen J, Ahmad NN, et al. Complications of video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy in patients with interstitial lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1140ŌĆō1144.

20. Mouroux J, Clary-Meinesz C, Padovani B, et al. Efficacy and safety of videothoracoscopic lung biopsy in the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;11:22ŌĆō24; , 25-26.

21. Ravaglia C, Bonifazi M, Wells AU, et al. Safety and diagnostic yield of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases: a comparative study versus video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy and a systematic review of the literature. Respiration 2016;91:215ŌĆō227.

22. Tomassetti S, Wells AU, Costabel U, et al. Bronchoscopic lung cryobiopsy increases diagnostic confidence in the multidisciplinary diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:745ŌĆō752.

23. Brownell R, Moua T, Henry TS, et al. The use of pretest probability increases the value of high-resolution CT in diagnosing usual interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2017;72:424ŌĆō429.

24. Richeldi L, Wilson KC, Raghu G. Diagnosing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in 2018: bridging recommendations made by experts serving different societies. Eur Respir J 2018;52:1801485.

26. Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1004ŌĆō1014.

27. Flaherty KR, King TE Jr, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:904ŌĆō910.

Diagnostic approach for IPF. IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; MDD, multidisciplinary discussion; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; SLB, surgical lung biopsy; ILD, interstitial lung disease.

Figure┬Ā1.

High-resolution computed tomography scan images demonstrating (A) air-trapping from an expiratory phase scan (right) compared to inspiratory phase (left) and (B) change of dependent opacity on prone (right) position from supine (left) position.

Figure┬Ā2.

High-resolution computed tomography images demonstrating (A) UIP pattern, (B) probable UIP, (C) indeterminate for UIP,

and (D) alternative diagnosis (multiple air-trapping) according to the 2018 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT guidelines. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; JRS, Japanese Respiratory Society; ALAT, Latin American Thoracic Society.

Figure┬Ā3.

Histopathologic patterns demonstrating (A) Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). In low power field (left, ├Ś12.5), lung parenchyma is involved by extensive interstitial fibrous thickening, which is centered in subpleural or interlobular septal region. The central lung parenchyma is relatively uninvolved. In high power field (right, ├Ś100), several fibroblastic foci and old mature fibrosis are mixed up with each other. Mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltration is also noted, but it is scarce. (B) Probable UIP. In low power field (left, ├Ś12.5), lung parenchyma is involved by subpleural and interlobular septal patchy interstitial fibrosis. However, the fibrosis extent is relatively scarce. No microscopic honeycomb change is shown. In high power field (right, ├Ś100), several fibroblastic foci intermixed with old mature fibrosis is observed, which indicates temporal heterogeneity. (C) Indeterminate for UIP. In low power field (left, ├Ś12.5), patchy interstitial fibrosis located in subpleural and centrilobular region is noted. In high power field (right, ├Ś100), old mature fibrosis with fibroblastic foci is identified. These features possibly represent UIP, but chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis can be suspected because a significant amount of centrilobular fibrosis component is shown. (D) Alternative diagnosis. In low power field (left upper, ├Ś12.5), well-defined, stellate-shaped subpleural lung fibrosis with adjacent parenchymal cystic change is noted. In high power field (right upper, ├Ś100), a large amount of mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, mononuclear cell and eosinophil-predominated, is shown. On immunohistochemistry, these mononuclear cells are diffuse and strongly immunoreactive for anti-CD1a (left lower, ├Ś400) and langerin (right lower, ├Ś400) antibodies. These features are consistent with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; JRS, Japanese Respiratory Society; ALAT, Latin American Thoracic Society.

Figure┬Ā4.

Table┬Ā1.

High-resolution computed tomography scanning patterns

Table┬Ā2.

Histopathology pattern and features

UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; JRS, Japanese Respiratory Society; ALAT, Latin American Thoracic Society; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IIP, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; HP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis; PCLH, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis; LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 17,515 View

- 1,222 Download

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print