1. Austin MA, Hutter CM, Zimmern RL, Humphries SE. Genetic causes of monogenic heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: a HuGE prevalence review. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:407вҖ“420.

2. Benn M, Watts GF, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Mutations causative of familial hypercholesterolaemia: screening of 98 098 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study estimated a prevalence of 1 in 217. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1384вҖ“1394.

3. Lee SJ, Kwark JK, Koh KA, Choi WH, Park WK, Kim SW. A case of familial hypercholesterolemia combined with diabetes mellitus. Korean J Med 1989;37:558вҖ“565.

4. You JH, Kil HR, Seo JJ, Chung YH. A case of familial hypercholesterolemia. J Korean Pediatr Soc 1989;32:1288вҖ“1294.

5. Authors/Task Force Members; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); ESC National Cardiac Societies. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 2019;290:140вҖ“205.

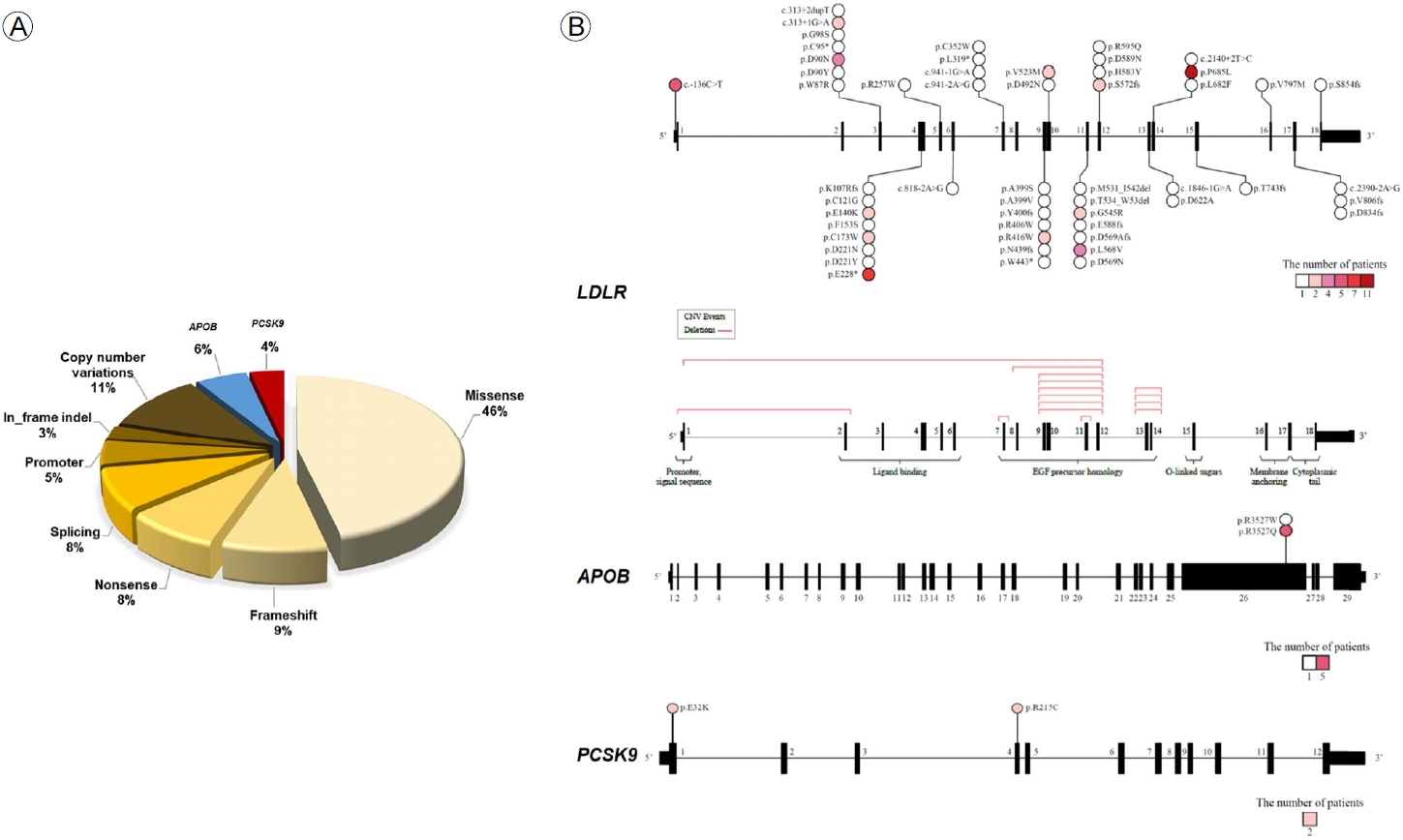

7. Kim H, Lee CJ, Kim SH, et al. Phenotypic and genetic analyses of Korean patients with familial hypercholesterolemia: results from the KFH Registry 2020. J Atheroscler Thromb 2022;29:1176вҖ“1187.

9. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3478вҖ“3490.

10. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889вҖ“2934.

11. Perez de Isla L, Alonso R, Mata N, et al. Predicting cardiovascular events in familial hypercholesterolemia: the SAFEHEART Registry (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study). Circulation 2017;135:2133вҖ“2144.

12. Shin DG, Han SM, Kim DI, et al. Clinical features of familial hypercholesterolemia in Korea: predictors of pathogenic mutations and coronary artery disease: a study supported by the Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015;243:53вҖ“58.

13. Schmidt EB, Hedegaard BS, Retterstol K. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: history, diagnosis, screening, management and challenges. Heart 2020;106:1940вҖ“1946.

14. Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Okamura T, et al. Multicenter study to determine the diagnosis criteria of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb 2012;19:1019вҖ“1026.

15. Brunham LR, Ruel I, Aljenedil S, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on familial hypercholesterolemia: update 2018. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:1553вҖ“1563.

16. Starr B, Hadfield SG, Hutten BA, et al. Development of sensitive and specific age- and gender-specific low-density lipoprotein cholesterol cutoffs for diagnosis of first-degree relatives with familial hypercholesterolaemia in cascade testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:791вҖ“803.

17. Sturm AC, Knowles JW, Gidding SS, et al. Clinical genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:662вҖ“680.

18. Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Nohara A, Inazu A, Mabuchi H, Yamagishi M. Impact of clinical signs and genetic diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia on the prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with severe hypercholesterolaemia. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1573вҖ“1579.

19. Chora JR, Iacocca MA, Tichy L, et al. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) Familial Hypercholesterolemia Variant Curation Expert Panel consensus guidelines for

LDLR variant classification. Genet Med 2022;24:293вҖ“306.

24. Brahm AJ, Hegele RA. Combined hyperlipidemia: familial but not (usually) monogenic. Curr Opin Lipidol 2016;27:131вҖ“140.

26. Representatives of the Global Familial Hypercholesterolemia Community, Wilemon KA, Patel J, et al. Reducing the clinical and public health burden of familial hypercholesterolemia: a global call to action. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:217вҖ“229.

28. Raal FJ, Hovingh GK, Catapano AL. Familial hypercholesterolemia treatments: guidelines and new therapies. Atherosclerosis 2018;277:483вҖ“492.

29. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/ AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/N LA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:e285вҖ“e350.

33. Besseling J, Hovingh GK, Huijgen R, Kastelein JJ, Hutten BA. Statins in familial hypercholesterolemia: consequences for coronary artery disease and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:252вҖ“260.

35. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2387вҖ“2397.

36. Tsujita K, Sugiyama S, Sumida H, et al. Impact of dual lipid-lowering strategy with ezetimibe and atorvastatin on coronary plaque regression in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: the multicenter randomized controlled PRECISE-IVUS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:495вҖ“507.

38. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1713вҖ“1722.

39. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2097вҖ“2107.

40. Landmesser U, Chapman MJ, Stock JK, et al. 2017 Update of ESC/EAS Task Force on practical clinical guidance for proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibition in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1131вҖ“1143.

41. Nohara A, Ohmura H, Okazaki H, et al. Statement for appropriate clinical use of

PCSK9 inhibitors. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018;25:747вҖ“750.

42. Raal FJ, Santos RD, Blom DJ, et al. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, for lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:998вҖ“1006.

43. Cuchel M, Meagher EA, du Toit Theron H, et al. Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2013;381:40вҖ“46.

44. Raal FJ, Kallend D, Ray KK, et al. Inclisiran for the treatment of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1520вҖ“1530.

45. Rosenson RS, Burgess LJ, Ebenbichler CF, et al. Evinacumab in patients with refractory hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2307вҖ“2319.

46. Raal FJ, Rosenson RS, Reeskamp LF, et al. Evinacumab for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020;383:711вҖ“720.

47. EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC). Global perspective of familial hypercholesterolaemia: a cross-sectional study from the EAS Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Studies Collaboration (FHSC). Lancet 2021;398:1713вҖ“1725.

48. Santos RD, Gidding SS, Hegele RA, et al. Defining severe familial hypercholesterolaemia and the implications for clinical management: a consensus statement from the International Atherosclerosis Society Severe Familial Hypercholesterolemia Panel. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016;4:850вҖ“861.

49. Gidding SS, Champagne MA, de Ferranti SD, et al. The agenda for familial hypercholesterolemia: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;132:2167вҖ“2192.

51. Santos RD, Ruzza A, Hovingh GK, et al. Evolocumab in pediatric heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1317вҖ“1327.

52. Graham DF, Raal FJ. Management of familial hypercholesterolemia in pregnancy. Curr Opin Lipidol 2021;32:370вҖ“377.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print