|

|

| Korean J Med > Volume 97(3); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

The prevalence of ischemic heart disease is steadily growing as populations age. Antithrombotic treatment is a key therapeutic modality for the prevention of secondary cerebro-cardiovascular disease. Patients with acute coronary syndrome or who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention must be treated with dual antiplatelet therapy for a mandatory period. The optimal perioperative antithrombotic regimen remains debatable; antithrombotics can cause bleeding. Inadequate antithrombotic regimens are associated with perioperative ischemic events, but continuation of therapy may increase the risks of perioperative hemorrhagic complications (including mortality). Many guidelines on the perioperative management of antithrombotic agents have been established by academic societies. However, the existing guidelines do not cover all specialties, nor do they describe the thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks associated with various surgical interventions. Moreover, few practical recommendations on the modification of antithrombotic regimens in patients who require non-deferrable interventions/surgeries or procedures associated with a high risk of hemorrhage have appeared. Therefore, cardiologists, specialists performing invasive procedures, surgeons, dentists, and anesthesiologists have not come to a consensus on optimal perioperative antithrombotic regimens. The Korean Platelet-Thrombosis Research Group presented a positioning paper on perioperative antithrombotic management. We here discuss commonly encountered clinical scenarios and engage in evidence-based discussion to assist individualized, perioperative antithrombotic management in clinical practice.

Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņ¦łĒÖśņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×Éļōż ņżæ ņĢĮ 10%ļŖö ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 1ļģä ļé┤ņŚÉ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņä▒ ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[1,2]. ņØ┤ļōż ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒĢäņŚ░ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤Ćņ¦łĒÖś ļ░£ņāØņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ņāüņŖ╣ĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉśļ»ĆļĪ£ ņŻ╝ņØśļź╝ ņÜöĒĢ£ļŗż[3-5]. ņØ┤ļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņżæļŗ©ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļ░śļÅÖ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝(rebound effect)ņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚś(thrombotic risk) ņ”ØĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ņŻ╝ ņøÉņØĖņØ┤ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņłśņłĀ ņ×Éņ▓┤ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ£ ņŖżĒŖĖļĀłņŖżļéś ĻĄÉĻ░ÉņŗĀĻ▓ĮņØś ĒĢŁņ¦ä, ĒśłĻ┤Ć Ļ▓ĮļĀ© ļ░Å ņŻĮņāüĻ▓ĮĒÖöļ░śņŚÉ Ļ░ĆĒĢ┤ņ¦ĆļŖö ņĀäļŗ© ņØæļĀź(shear stress) ļō▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ┤ ĒśłņĀä ļ░£ņāØņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ļåÆņĢäņ¦äļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ņłśņłĀ ņ×Éņ▓┤ļÅä ņŚ╝ņ”ØņØś ļ░£ņāØņØ┤ļéś ņØæĻ│ĀĻ│äņØś ĒÖ£ņä▒ĒÖöļź╝ ņĪ░ņןĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉśļ»ĆļĪ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖĻ░Ć ņéĮņ×ģļÉ£ ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│╝ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖĻ░Ć ņéĮņ×ģļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ ĒśłĻ┤Ć ļ¬©ļæÉņŚÉņä£ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤(thrombotic event)ņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉ£ļŗż[6-8].

Ēśäņ×¼ ĻĄŁĻ░Ćļ│ä ļ░Å ņ£ĀĻ┤Ć ĒĢÖĒÜī ļ│äļĪ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉļōżņØś ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņä▒ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļŗżņØīĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż[9-14]. ņ▓½ņ¦Ė, ņŗ¼ņןļé┤Ļ│╝ņØś, ņÖĖĻ│╝ņØś ļ░Å ļ¦łņĘ©Ļ│╝ņØś ļ¬©ļæÉņØś Ļ│ĄĒåĄļÉ£ ņØśĻ▓¼ņØ┤ ļ░śņśüļÉ£ Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņĢäļŗłļ»ĆļĪ£ ņĀäĻ│ĄļČäņĢ╝ ļ│äļĪ£ ņ╣śļŻīņØś ĒåĄņØ╝ņØä ņØ┤ļŻ©ĻĖ░ Ēלļōżļŗż. ļæśņ¦Ė, ņłśņłĀ ņóģļ│äļĪ£ Ēæ£ņżĆĒÖöļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ņģŗņ¦Ė, ĒÖśņ×É Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚś(bleeding risk)ņØä Ēæ£ņżĆĒÖöĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ļäĘņ¦Ė, ņłśņłĀņØä ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢĀ ņłś ņŚåņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļéś ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ē ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņĪ░ņĀłņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłņØ┤ ņŚåļŗż.

ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ļōżņØĆ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀ ņŗ£ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņżæļŗ©ņŚåņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīņ£ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņŗżņĀ£ ņ×äņāüņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØś ņżæļŗ©ņØ┤ ļ╣łļ▓łĒ׳ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[15]. ļśÉĒĢ£ perioperative ischemic evaluation 2 (POISE-2) ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ¦łĒÖśņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņŻ╝ņÜöņŗ¼ņןņé¼Ļ▒┤(major adverse cardiovascular event, MACE)ņØś Ļ░Éņåī ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ ņŚåņØ┤ ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤(bleeding event)ļ¦ī ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé©ļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż[16]. ļ░śļ®┤ņŚÉ, ņØ┤ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ĒĢśņ£ä ļČäņäØņŚÉņä£ļŖö Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ ļ│æļĀźņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņŗ¼ĻĘ╝Ļ▓Įņāēņ”Ø ļ░£ņāØņØä ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņżäņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļéś ņŻ╝ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņÖĆļŖö ņāüļ░śļÉ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝Ļ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[17]. ļśÉĒĢ£, ĒĢśļéś ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×Éļź╝ Ļ░Ćņ¦ä 220ļ¬ģņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņ£äņĢĮĻĄ░Ļ│╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢĀ ļĢī MACE ļ░£ņāØņØś ņāüļīĆņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ 80% Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£ĒéżļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼Ļ│Ā ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØĆ ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēéżņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż[18]. ņĢ×ņä£ ņ¢ĖĻĖēĒĢ£ ņāüļ░śļÉ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļōżļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ┤ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņ¦łĒÖśņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØä ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļŖöņ¦ĆņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņŚ¼ņĀäĒ׳ ļģ╝ļ×ĆņØ┤ ņ¦ĆņåŹļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż.

ļīĆĒĢ£ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤Ćņżæņ×¼ĒĢÖĒÜī ņé░ĒĢś ĒśłņåīĒīÉ-ĒśłņĀä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ĒÜīņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņ×äņāüņŚÉņä£ ļ¦łņŻ╝ņ╣śĻ▓ī ļÉśļŖö ļ│Ąņ×ĪĒĢ£ ņāüĒÖ®ņŚÉ ļÅäņøĆņØä ņŻ╝ĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ ņĢĮņĀ£ ņĪ░ņĀłņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ņĄ£ņŗĀ ņ¦ĆĻ▓¼Ļ│╝ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ĒÜīņØś ņ×ģņןņØä ļīĆĒæ£ņĀüņØĖ ņ×äņāü ņ”ØļĪĆņÖĆ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢśļĀż ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļ╣äņŖżĒģīļĪ£ņØ┤ļō£ ņåīņŚ╝ņĀ£ļź╝ ļ╣äļĪ»ĒĢ£ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļōżņØ┤ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒśłņĀä ļ░Å ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣śņ¦Ćļ¦ī Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ņČ®ļČäĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä ļ│Ė ĒĢ®ņØśļ¼ĖņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņāØļץĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢśĻ▓Āļŗż.

ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØĆ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļé£ĒĢ┤ĒĢ£ ņØ╝ņØ┤ļ®░ ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ© ļśÉļŖö ņ¦ĆņåŹņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņŗ¼ņןļé┤Ļ│╝ņØśņÖĆ ņÖĖĻ│╝ņØś Ļ░äņØś ņØśĻ▓¼ ļČłņØ╝ņ╣śĻ░Ć ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦Äļŗż. ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĢĮņĀ£ ņżæļŗ©ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ£ ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņØś ņ”ØĻ░Ć, ņłśņłĀņØä ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢī ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņ£äĒŚśļÅä, ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢī ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ļŗżļ®┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ ņŗ¼ņןļé┤Ļ│╝ņØś, ņÖĖĻ│╝ņØś ļ░Å ļ¦łņĘ©Ļ│╝ņØś Ļ░äņØś ļŗżĒĢÖ ņĀ£ņ¦äļŻīļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņ╣śļŻī ņĀäļץņØä ņłśļ”ĮĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. Ēśäņ×¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØś ļīĆļץņĀüņØĖ ņøÉņ╣ÖņØĆ ļŗżņØīĻ│╝ Ļ░Öļŗż[10,13]. ņ▓½ņ¦Ė, ņØ┤ņżæĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņÜöļ▓Ģ(dual antiplatelet therapy, DAPT)ņØś ĒĢäņłś ņé¼ņÜ®ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢł ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀ(elective surgery)ņØĆ ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļæśņ¦Ė, ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņ¦ĆĒśłņØ┤ ĒלļōĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņÖĖņŚÉļŖö ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØĆ ņżæļŗ©ņŚåņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņģŗņ¦Ė, ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ĒÖśņ×É Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ĒśłņĀä ļ░Å ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØä ļŗżĻ░üņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ¦×ņČżĒśĢ ņ╣śļŻī ņĀäļץņØä ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ® ņøÉņ╣ÖņØĆ ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£äņŗ£ĒŚśņØä ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ņ”Øļ¬ģĒĢśĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ņĀ£ņĢĮņØ┤ ļ¦ÄņĢä Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļéś ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░ĆņØś ņØśĻ▓¼ņØä ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ļĪ£ ņłśļ”ĮļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░ ņĀäĻ│Ą ņśüņŚŁļ│äļĪ£ ņāüņØ┤ĒĢ£ ņ×ģņןņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤Ļ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣© ņłśĒ¢ēļźĀļÅä ļåÆņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż[9-14].

ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉņØś ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚś ĒÅēĻ░Ć Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØĆ ļŗżņØīĻ│╝ Ļ░Öļŗż. ņ▓½ņ¦Ė, ĒÖśņ×É Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ņ×äņāüņĀü ĒŖ╣ņä▒ ļśÉļŖö Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØ┤ Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ņØś ņä▒ņāüņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖöņ¦Ć ĒīīņĢģĒĢ£ļŗż (Table 1) [10,13]. ļæśņ¦Ė, ņŗ£ņłĀ ļ░®ļ▓ĢĻ│╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņóģļźś ļ░Å Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀĻ╣īņ¦ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØä ņóģĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£ ĒśłņĀäņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢ£ļŗż(Table 2) [10,13]. ņģŗņ¦Ė, ņłśņłĀ ņóģļ│äļĪ£ Ļ▓░ņĀĢļÉ£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśĻ│╝ ņĢ×ņä£ ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØä ņóģĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŗ£ĻĖ░ņÖĆ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ© ļ░Å ņ×¼Ļ░£ ņŗ£ĻĖ░ļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ£ļŗż (Table 3; Supplementary Table 1) [10,13]. ņāüĻĖ░ Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ņóĆ ļŹö ņäĖļ░ĆĒĢśĻ▓ī ņĀ£Ļ│ĄĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ņןņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ņ£╝ļéś ņŗżņĀ£ ņ×äņāüņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ļ▓łĻ▒░ļĪ£ņÜ┤ ņĀÉņØ┤ ļ¦ÄĻ│Ā ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØä ļ¬©ļōĀ ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ Ļ░ĢņĀ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņÖĖĻ│╝ņØśļōżņØś ņĀĆĒĢŁļÅä ņāüļŗ╣ĒĢśļŗż.

ņłśņłĀĻ│╝ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØĆ ņłśņłĀ Ēøä 30ņØ╝ ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö MACEņØś ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØä ĻĖ░ņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀĆņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░(< 1%), ņżæļō▒ļÅäņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░(1-5%), ļ░Å Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░(Ōēź 5%)ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäļźśļÉ£ļŗż[14]. ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö MACEļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņ×äņāüņĀü ĒŖ╣ņä▒, Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒, ņŗ£ņłĀņØś ļ│Ąņ×ĪļÅä, ņØæĻ│ĀĻ│äņØś ĒÖ£ņä▒ļÅä ļ░Å ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņóģļźś ļō▒ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņøÉņØĖņØś ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ░øĻ▓ī ļÉśļ»ĆļĪ£ Ēæ£ņżĆĒÖöļÉ£ ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ņĀ£Ļ│ĄĒĢśĻĖ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦żņÜ░ Ēלļōżļŗż[19]. ņāüĻĖ░ ņøÉņØĖļōż ņżæ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀļČĆĒä░ ņłśņłĀĻ╣īņ¦Ć Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļ░Å ņłśņłĀ ņĀä DAPTņØś ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ņżæļŗ© ņŚ¼ļČĆĻ░Ć ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ ļ░£ņāØņŚÉ Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņÜöņØĖņØ┤ļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£ĻĖ░ņÖĆ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä DAPTņØś ņżæļŗ© ņŚ¼ļČĆļŖö ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖ ņé¼ņÜ® ņŚ¼ļČĆ, ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņóģļźś, ņ×äņāüņĀü ļ░Å Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņ¦Ģ ļō▒ņØä ņóģĒĢ®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ£ Ēøä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ļéśņØ┤, ļŗ╣ļć©ļ│æ, ņŗĀļČĆņĀä, ņŗ¼ļČĆņĀä ļ░Å ņóīņŗ¼ņŗżĻĄ¼ĒśłļźĀ ļō▒ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉĻ░Ć ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ļ░£ņāØņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣śļ®░ ĻĖēņä▒Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņ”ØĒøäĻĄ░ņØś ļ│æļĀź, ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖĒśłņĀäņ”ØņØś ļ│æļĀź, ņŗ¼ĻĘ╝Ļ▓Įņāēņ”ØņØś ņ×¼ļ░£ ļ│æļĀź ļō▒ļÅä ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉļōżņØ┤ļŗż(Table 1) [10,13]. ņāüĻĖ░ņØś ņ×äņāü ņ¢æņāüļōżĻ│╝ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒Ļ│╝ ņŗ£ņłĀņØś ļ│Ąņ×ĪļÅä ļśÉĒĢ£ ņČ®ļČäĒ׳ Ļ│ĀļĀż Ēøä ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ© ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ ĒīÉļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż(Table 1). ļ│æļ│ĆņØś ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ┤ 3Ļ░£ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖĻ░Ć ņéĮņ×ģļÉśņŚłĻ▒░ļéś 3ĻĄ░ļŹ░ ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļ│æļ│ĆņØä ņ╣śļŻīĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ░Å ļČäņ¦Ćļ│æļ│ĆņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļō▒ņØĆ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņāüņŖ╣ĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņŻ╝ņØśļź╝ ņÜöĒĢ£ļŗż[10,13]. ļśÉĒĢ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņóīņŻ╝Ļ░äļČĆ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļ®┤ ņ╣śļ¬ģņĀüņØĖ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ┤łļלĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ļ│æļ│ĆņŚÉ ņŗ£ņłĀņØä ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ©ņØä Ēö╝ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀ ĒøäļČĆĒä░ ņłśņłĀĻ╣īņ¦Ć Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØĆ DAPT ņżæļŗ©ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ ļ░£ņāØņØś Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņøÉņØĖ ņżæ ĒĢśļéśņØ┤ļŗż. ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØĆ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀ ĒøäļČĆĒä░ ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉśĻĖ░Ļ╣īņ¦ĆņØś ņŗ£Ļ░äĻ│╝ ļ░ĆņĀæĒĢ£ Ļ┤ĆĻ│äĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĻĘĖ ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░Ļ░Ć ļÉśļŖö ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņØ┤ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĖ░ņłĀņØä ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśĻ▓ī ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ņØś ņ¦ĆņåŹ ļśÉļŖö ņżæļŗ©Ļ│╝ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ ļ░£ņāØ ņé¼ņØ┤ņØś ņØĖĻ│╝Ļ┤ĆĻ│äļź╝ ĻĘ£ņĀĢĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ¢┤ļĀżņÜ┤ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦Äļŗż[20-23].

ņłśņłĀņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļŖö ņ▓½ 1ļģä ļÅÖņĢł ņāüņŖ╣ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĻĘĖ ņØ┤ĒøäņŚÉļŖö ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņÖĆ ļÅÖņØ╝ĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ĒśäĒ¢ē Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀ Ēøä 1ļģä ļé┤ņŚÉ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņä▒ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ņśłņĖĪņŚÉ ņŻ╝ņĢłņĀÉņØä ļæÉĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[12,14]. ļŹ┤ļ¦łĒü¼ņŚÉņä£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļ░®ņČ£ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖ(drug eluting stent, DES)ļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģ Ēøä 1Ļ░£ņøöņØ┤ ņ¦Ćļéśļ®┤ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ ņŚåļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņÖĆ ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢ£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ņŗ¼ĻĘ╝Ļ▓Įņāēņ”Ø ļ░£ņāØļźĀĻ│╝ ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļéś ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 1-3Ļ░£ņøöņØ┤ ņ¦Ćļéśļ®┤ Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ņØś ņ×äņāü ņ¢æņāüņØ┤ ņŚåĻ│Ā ļ│Ąņ×ĪĒĢ£ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņĢłņĀäĒĢśĻ▓ī ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż[6]. ļŗżļźĖ ļ¦ÄņØĆ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņłśņłĀĻ│╝ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ņ”ØĻ░ĆļŖö 3-6Ļ░£ņøö ĒøäļČĆĒä░ ņĢłņĀĢĒÖöļÉ£ļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[21,24]. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņżæņ×¼ņłĀ Ēøä ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀņØĆ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ 6Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ĒøäļĪ£ ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņāüĻĖ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ļōżņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ® ņŚ¼ļČĆņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ĒśłņĀä ļ░Å ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļČäņäØ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņĀ£ņŗ£ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀņØä ņ¢ĖņĀ£Ļ╣īņ¦Ć ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØĖĻ░ĆņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĖ░ņżĆņØĆ ņ£Āļ¤ĮĻ│╝ ļ»ĖĻĄŁņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉļÅä ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż[12,14]. ņ£Āļ¤Įņŗ¼ņןĒĢÖĒÜīņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļ®┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņŚÉ ņāüĻ┤ĆņŚåņØ┤ ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 1Ļ░£ņøöņØ┤ ņ¦Ćļéśļ®┤ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļŖö ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳Ļ│Ā ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀļÅä Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[14]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĻĖēņä▒Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņ”ØĒøäĻĄ░ņØ┤ļéś ļ│Ąņ×ĪĒĢ£ ņŗ£ņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ 6Ļ░£ņøö ļÅÖņĢł DAPTļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśĻ│Ā ņłśņłĀ ļśÉĒĢ£ ņØ┤ ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢłņØĆ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[14]. ļ»ĖĻĄŁņŗ¼ņןĒĢÖĒÜīņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņØ╝ļ░śĻĖłņåŹņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖ(bare metal stent, BMS)ļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ 30ņØ╝ņØ┤ Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ĒĢśļ®┤ ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳Ļ│Ā DESļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ 3Ļ░£ņøöĻ░äņØĆ ņØæĻĖē ņāüĒÖ®ņØä ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ ņłśņłĀņØĆ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[12]. ļ¦īņĢĮ, DAPT ņżæļŗ©Ļ│╝ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśļ│┤ļŗż ņłśņłĀņØä ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢī ņśłņāüļÉśļŖö ņ¦łĒÖśņØś ņ¦äĒ¢ē ļśÉļŖö ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”Ø ļ░£ņāØņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ļŹö ļåÆļŗżļ®┤ DESļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģĒĢśņśĆļŹöļØ╝ļÅä 3-6Ļ░£ņøöņŚÉ ņŗ£Ē¢ēņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[12].

ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖ ņĀ£ņ×æ ĻĖ░ņłĀņØś ļ░£ņĀäĻ│╝ ļŹöļČłņ¢┤ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ĒÜŹĻĖ░ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļŖö DAPT ņé¼ņÜ® ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļŗ©ņČĢņØś ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░Ļ░Ć ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[24-27]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņŗ£ņłĀ ĒśłĻ┤ĆņØś ĻĖ░ļŖź ĒÜīļ│ĄĻ│╝ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖĻ░Ć ņéĮņ×ģļÉ£ ĒśłĻ┤ĆņØś ņ×¼ņāüĒö╝ĒÖöĻ░Ć ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉśļŖö ņłśĻ░£ņøö ļÅÖņĢł ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØä ņśłļ░®ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ DAPTļź╝ ņØ╝ņĀĢ ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[12,14]. ĒÆŹņäĀņä▒ĒśĢņłĀļ¦īņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ╣śļŻīĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØä ļåÆņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņ×äņāü ņ¢æņāüņØ┤ļéś Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØ┤ ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 2ņŻ╝Ļ░Ć Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ĒĢśļ®┤ DAPTņØś ņżæļŗ©ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ ļ│╝ ņłś ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĒÆŹņäĀņä▒ĒśĢņłĀļ¦īņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ╣śļŻīĒĢśļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņ×äņāüņĀü ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĄ£ņåī 1Ļ░£ņøö ļÅÖņĢłņØĆ DAPTļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż(Table 2) [12].

ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņóģļźśņÖĆ ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀ Ēøä ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ ļ░£ņāØ ņé¼ņØ┤ņØś ņŚ░Ļ┤Ćņä▒ņØĆ ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż. 1ņäĖļīĆ DESņÖĆ BMS ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ Ontario stent registryņŚÉņä£ļŖö BMSļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö 46-180ņØ╝ ņé¼ņØ┤ņŚÉ, 1ņäĖļīĆ DESļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö 180ņØ╝ ņØ┤ĒøäņŚÉ ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņĀüĒĢ®ĒĢśļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż[28]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļśÉ ļŗżļźĖ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 6Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ĒøäņŚÉ ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņóģļźśļŖö ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ļ░£ņāØĻ│╝ ļ¼┤Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż[15,29]. Ēśäņ×¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö DESļŖö 1ņäĖļīĆ DESļ│┤ļŗż ņÜ░ņłśĒĢ£ ņĢłņĀĢņä▒ņØä ĒÖĢļ│┤ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņéĮņ×ģ ļÉ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņóģļźśļ│┤ļŗżļŖö ņŗ£ņłĀņØś ļ│Ąņ×Īņä▒(ņ╣śļŻīĒĢ£ ĒśłĻ┤Ć ņłś, ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖņØś ņ┤Ø ņłśņÖĆ ņ┤Ø ĻĖĖņØ┤, ļ│æļ│ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒)ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ DAPT ņé¼ņÜ® ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļ░Å ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØś ņŗ£ĻĖ░ļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ļŹö ņĀüņĀłĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉśļéś Ē¢źĒøä ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ£ ņ”Øļ¬ģņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[30].

ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤Ćņ¦łĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀ ņżĆļ╣ä ņżæ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņ¦ĆņåŹ ļśÉļŖö ņżæļŗ©ņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ ļĢī ĒśłņĀä ļ░Å ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØä ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ╣śļŻī ņĀäļץņØä ņłśļ”ĮĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØĆ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņĀĆņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░, ņżæļō▒ļÅäņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ ļ░Å Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäļźśļÉśĻ│Ā ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļŖö ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ļ░£ņāØ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļ│┤ļŗżļŖö ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņ¦ĆĒśłņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ņ¦ĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢļÉ£ļŗż[10,12-14].

ļ»ĖĻĄŁĻ│╝ ņ£Āļ¤ĮņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņĢĮ 250Ļ░£ņØś ņłśņłĀņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ĻĘ£ņĀĢĒĢ┤ ļåōĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ ņØ┤ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņČ£Ēśł ņä▒Ē¢źņØ┤ļéś ļé┤ņ×¼ņĀü ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļ│┤ļŗżļŖö ņłśņłĀ ņ×Éņ▓┤ņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ĻĖ░ļ░śņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ×æņä▒ļÉśņŚłļŗż(Supplementary Table 1) [10,12-14]. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ļČäļźśļŖö ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ņĢäļŗī Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļéś ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░ĆņØś ņØśĻ▓¼ņØä ļ░öĒāĢņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀ£ņĀĢļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ļŗ©ņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳Ļ│Ā ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņä▒Ļ│ĄņĀüņØĖ ņ¦ĆĒśł ņŚ¼ļČĆļŖö ņ¦æļÅäņØśņØś ņłÖļĀ©ļÅäņÖĆ ņ¦üņĀæņĀüņØĖ ņŚ░Ļ┤Ćņä▒ņØ┤ ņ׳ņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£ ņ¦æļÅäņØśļéś ņØśļŻīĻĖ░Ļ┤Ć Ļ░äņØś ņ¦äļŻīņØś ĒÄĖņ░©Ļ░Ć ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö ņŻ╝ņÜöĒĢ£ ņøÉņØĖņØ┤ ļÉ£ļŗż[10,12-14].

Ēśäņ×¼ ļ»ĖĻĄŁ ļ░Å ņ£Āļ¤ĮņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ¦äļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņøÉņ╣ÖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ļé«ņØĆ(ņĀĆņ£äĒŚśļÅä) ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøäņŚÉ DAPTļź╝ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīņ£ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ ņżæļō▒ļÅä ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņØś ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØĆ ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśĻ│Ā P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļŖö Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīņ£ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[10,12-14]. ļśÉĒĢ£, ĒśłĻ┤Ćņ×¼Ļ▒┤ņłĀ, ļ│Ąņ×ĪĒĢ£ ļé┤ņן ņłśņłĀ, ņŗĀĻ▓ĮņÖĖĻ│╝ņĀü ņłśņłĀ ļ░Å Ļ▓ĮĻĖ░Ļ┤Ćņ¦Ć ņłśņłĀĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ Ļ│ĀņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļÅä ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņŗ£ĻĖ░ņŚÉ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż(Table 3; Supplementary Table 1) [12,14]. ĒÖśņ×É Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ ņä▒ļ│ä, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ļ░Å ļÅÖļ░ś ņ¦łĒÖśņØä ļ░öĒāĢņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ¬ć Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ĒÅēĻ░ĆļÅäĻĄ¼ļōżņØ┤ Ļ░£ļ░£ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉ ĒŖ╣ĒÖöļÉ£ ļÅäĻĄ¼ļōżņØĆ ņĢäļŗłļŗż[31-33].

ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņ¦ĆĒśłņØ┤ ņČ®ļČäĒ׳ ļÉśņŚłļŗżĻ│Ā ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉśļ®┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ļ╣©ļ”¼ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ļź╝ ņ×¼Ļ░£ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØśļ»Ė ņ׳ļŖö ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņ×¼ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ņ¦ĆĒśłņØ┤ ņČ®ļČäĒ׳ ļÉĀ ļĢīĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļåÆņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņśłņāüļÉĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ│ĄĻ░ĢĻ▓Į ņłśņłĀ, ļĪ£ļ┤ć ņłśņłĀ ļśÉļŖö ļĀłņØ┤ņĀĆ ņłśņłĀ ļō▒ņØś ņĄ£ņåī ņ╣©ņŖĄ ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āļÅä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[10,13].

ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØĆ ĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ņłśņłĀņØä ļ»ĖļŻ░ ņłś ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉ ņØ╝ņŗ£ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ĒśĢ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ļīĆņŗĀ ņ×æņÜ® ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ņ¦¦ņØĆ ņĀĢļ¦źņŻ╝ņé¼ĒśĢ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ĻĄÉņ▓┤ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ļ¦ÉĒĢ£ļŗż[10]. ņĢäņ¦ü Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ļ¦Äņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀüņØæ ņ”ØņØ┤ ĒÖĢļ”ĮļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż. ņ£Āļ¤Įņŗ¼ņןĒĢÖĒÜī Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņżæņ×¼ņŗ£ņłĀ ņŗ£Ē¢ē Ēøä 1Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ ļ│╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżĻ│Ā ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[14].

Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņŚÉ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņĀĢļ¦źņŻ╝ņé¼ĒśĢ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļĪ£ļŖö ņ╣ĖĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼(cangrelor), Ēŗ░ļĪ£Ēö╝ļ░ś(tirofiban), ņĢ▒Ēŗ░Ēö╝ļ░öĒāĆņØ┤ļō£(eptifibatide) ļō▒ņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ĒŚżĒīīļ”░(heparin)Ļ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļŖö ņśżĒ׳ļĀż ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņØæņ¦æņØä ņĪ░ņןĒĢśĻ│Ā ĒśłņĀä ņāØņä▒Ļ│╝ ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ņ£äĒŚśņä▒ņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż[34]. ņĢäņ¦ü ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ¢┤ļĀżņÜ░ļéś ņ╣ĖĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļŖö Ēŗ░ļĪ£Ēö╝ļ░śņØ┤ļéś ņĢ▒Ēŗ░Ēö╝ļ░öĒāĆņØ┤ļō£ņÖĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņןņĀÉņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ņ╣ĖĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļŖö ņäĖ ņĢĮņĀ£ ņżæ ņ£ĀņØ╝ĒĢśĻ▓ī P2Y12ļź╝ ĒŖ╣ņØ┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņŗĀņןņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ░░ņäżļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņĪ░ņĀłĒĢĀ ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņŚåņ£╝ļ®░, Ļ░Ćņן ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░Ļ░Ć ņ¦¦Ļ│Ā(3-5ļČä) ņŻ╝ņ×ģ ņóģļŻī 1ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ĻĖ░ļŖźņØ┤ ĒÜīļ│ĄļÉ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, Ļ┤ĆļÅÖļ¦źņÜ░ĒÜīņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼(BRIDGE, bridging antiplatelet therapy with cangrelor in patients undergoing cardiac surgery)ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś ņ”ØĻ░ĆņŚåņØ┤ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņØæņ¦æ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż[35]. ņ╣ĖĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņØś ļ╣äņÜ®Ļ│╝ Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØś ņ¦ĆņåŹ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉ(prasugrel) ņżæļŗ© 3-4ņØ╝ ņØ┤Ēøä, Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ (ticagrelor) ļ░Å Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉ(clopidogrel) ņżæļŗ© 2-3ņØ╝ ņØ┤Ēøä ņĢĮņĀ£ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ļź╝ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśņŚ¼ ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£ņ×æ 1-6ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[36]. ņłśņłĀ Ēøä Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ļ░Ć Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ┤ņ¦Ćļ®┤ Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļéś ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉļ│┤ļŗżļŖö Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚś Ļ░Éņåīļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ┤ ņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ│Ā ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ņ×¼Ļ░£ ņŗ£ ļČĆĒĢś ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ Ēøä ņ£Āņ¦Ć ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢ£ļŗż[36].

Ēŗ░ļĪ£Ēö╝ļ░śĻ│╝ ņĢ▒Ēŗ░Ēö╝ļ░öĒāĆņØ┤ļō£ļŖö glycoprotein IIb/IIIa ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļĪ£ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ļź╝ ņ¦üņĀæņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņ£╝ļ®░ ņ×æņÜ® ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ļéś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. Ēŗ░ļĪ£Ēö╝ļ░śņØĆ 0.1 ╬╝g/kg/min, ņĢ▒Ēŗ░Ēö╝ļ░öĒāĆņØ┤ļō£ļŖö 2.0 ╬╝g/kg/minļź╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśļ®░ Ēü¼ļĀłņĢäĒŗ░ļŗī ņ▓Łņåīņ£©(creatinine clearance)ņØ┤ 50 mL/min ņØ┤ĒĢśņØ╝ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĀłļ░śņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśņŚ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ£ļŗż(Fig. 1). Ēł¼ņŚ¼ ņŗ£ņ×æņĀÉņØĆ ņ╣ĖĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņÖĆ ļÅÖņØ╝ĒĢśļ®░ ņłśņłĀ ņŗ£ņ×æ 4-6ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢś ņåīĻ▓¼ņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗżļ®┤ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ļŹö ļ╣©ļ”¼ ņżæļŗ©(8-12ņŗ£Ļ░ä)ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[10]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņØ┤ ņĢĮņĀ£ļōżņØś ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ”Øļ¬ģĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ ņłśņżĆņØ┤ ņĢĮĒĢ£ ņåīĻĘ£ļ¬© ņĀäĒ¢źņĀü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼, ĒøäĒ¢źņĀü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ļśÉļŖö ļ®öĒāĆņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļ░¢ņŚÉļŖö ņŚåņ¢┤ Ēśäņ×¼ Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░Ć ĻČīĻ│Āņé¼ĒĢŁ ņĀĢļÅäņØś ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ ņłśņżĆļ¦ī ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[10].

ņłśņłĀņØś ņóģļźśļéś ņŖżĒģÉĒŖĖ ņéĮņ×ģņłĀ ļŗ╣ņŗ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņāüĒÖ®ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ļ│ĆņłśĻ░Ć ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ® ļ░Å ņżæļŗ©ņØä Ļ░äļŗ©Ē׳ ņĀĢņØśĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØĆ ļ¦żņÜ░ Ēלļōżļŗż. ļīĆĻ░£ļŖö ņłśņłĀņØä ļ»ĖļŻ░ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļ®┤ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņØä ņĀĢļÅäļĪ£ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļé«ņĢäņ¦ä Ēøä ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ņłśņłĀĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗļŗż[14]. Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØ┤ļéś ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ņŚÉ ļ╣ä Ļ░ĆņŚŁņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓░ĒĢ®ĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ ņĢĮņĀ£Ļ░Ć Ļ▓░ĒĢ®ĒĢ£ ĒśłņåīĒīÉņØś ņłśļ¬ģņØ┤ ļŗż ĒĢĀ ļĢīĻ╣īņ¦Ć ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ĻĖ░ļŖź ņ¢ĄņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņ£Āņ¦ĆļÉ£ļŗż. Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ 5-7ņØ╝, ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ 7-10ņØ╝ ņĀĢļÅäņØś ņżæļŗ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļŖö P2Y12 ņłśņÜ®ņ▓┤ņŚÉ Ļ░ĆņŚŁņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓░ĒĢ®ĒĢśĻ│Ā ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░Ļ░Ć ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¦¦ņĢä(6-12ņŗ£Ļ░ä), Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØ┤ļéś ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉļ│┤ļŗż ļ╣Āļź┤Ļ▓ī ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņé¼ļØ╝ņ¦äļŗż(3-5ņØ╝) [36]. ņ£Āļ¤Įņŗ¼ņןĒĢÖĒÜī Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ P2Y12 ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØś ņĄ£ņåī ņżæļŗ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļŖö 3ņØ╝, Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ 5ņØ╝, ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ 7ņØ╝ļĪ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[14]. ļ░śļ®┤, ņØ┤Ēāłļ”¼ņĢäņŚÉņä£ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłņŚÉņä£ļŖö Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉĻ│╝ Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļŖö 5ņØ╝, ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØĆ 7ņØ╝ ņĀĢļÅäņØś ņżæļŗ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[10]. Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ņŚÉļŖö ļæÉĻ░£ļé┤ ļśÉļŖö ņ▓ÖņłśĻ░Ģļé┤ ņŗĀĻ▓ĮņÖĖĻ│╝ ņłśņłĀņØ┤ļéś ņÜöļÅäļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ£ ņĀäļ”ĮņäĀņĀłņĀ£ņłĀĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļåÆņØĆ ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ļ¦ī ņśłņÖĖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ ņżæļŗ©ņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśņśĆņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļ│┤ļŗż ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ ņżæļŗ©ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżĻ│Ā ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Supplementary Table 2) [37,38]. ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ļŖö DAPTļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņł£ņ£ĀĒĢ┤ ņ×äņāüņé¼ Ļ▒┤(net adverse clinical event)ņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēéżņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņןĻĖ░Ļ░ä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ MACEņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż[39,40]. ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ DAPT ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉņØś ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ņĢĮņĀ£ ņĪ░ņĀłņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ░£ņÜöļŖö ĻĘĖļ”╝ 2ņŚÉ ļéśĒāĆļé┤ņŚłļŗż.

ņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀ(urgent surgery)ņØĆ 48ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļé┤ņŚÉ ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļź╝ ņØśļ»ĖĒĢ£ļŗż. DAPTļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņØ┤ ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢł ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ļé©ņĢäņ׳ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ Ļ│╝ļÅäĒĢ£ ņČ£ĒśłņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļīĆļ╣äĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. Ēśäņ×¼ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ņ×æņÜ®ņØä ņŚŁņĀäņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņĢĮņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņŚåĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņłśĒśłņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ ļ│╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØä ņśłļ░®ĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ĻĖ░ļŖźņØä ĒÜīļ│ĄĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņłśĒśłļ¤ēņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ņ×ÉļŻīļŖö ļČĆņĪ▒ĒĢśļŗż[10]. ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņłśĒśłļÉ£ ĒśłņåīĒīÉņØś ĻĖ░ļŖźļÅä ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņłśĒśłņØĆ ļÉśļÅäļĪØ ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ĒÖ£ņä▒ ļīĆņé¼ ņé░ļ¼╝ (active metabolites)ņØ┤ ĒśłņżæņŚÉ ņ×öļźśĒĢśļŖö ļÅÖņĢłņØĆ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗļŗż. Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉĻ│╝ ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØś ĒÖ£ņä▒ ļīĆņé¼ ņé░ļ¼╝ņØĆ 6ņŗ£Ļ░ä, Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö 10-12ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢł ĒśłņżæņŚÉ ņ×öļźśĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØ┤ļéś ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ļ¦łņ¦Ćļ¦ē ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņäŁņĘ© Ēøä 4-6ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤Ēøä, Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö 10-12ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ĒøäņŚÉ ĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņłśĒśłņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[10].

ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ ņóģļŻī Ēøä ņ”ēņŗ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņ×¼Ļ░£ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ ĻĄŁļé┤ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö DESļź╝ ņéĮņ×ģ Ēøä ļ╣äņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ 8ņØ╝ ņØ┤ņāü ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņ×äņāü Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ļź╝ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ņĢģĒÖöņŗ£ĒéżļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśĒāĆļé¼ļŗż[38]. ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņĪ░ĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĒöäļØ╝ņłśĻĘĖļĀÉņØ┤ ļéś Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ļ│┤ļŗżļŖö Ēü┤ļĪ£Ēö╝ļÅäĻĘĖļĀÉņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ņłśņłĀ Ēøä 24-72ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ ņŗ¼ĒĢ£ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņŚåļŗżļ®┤ ļČĆĒĢśņÜ®ļ¤ē(600 mg)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ×¼Ļ░£ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢ£ļŗż[35]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŻ╝ņØśļź╝ ņÜöĒĢśļŖö ņČ£ĒśłņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņåī ĒīÉņĀ£ņØś ņ×¼Ļ░£ļź╝ ļ»ĖļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[10].

Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ĒśĢ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļŖö ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£(vitamin K antagonist, VKA)ņÖĆ ĒŖ╣ņĀĢ ņØæĻ│ĀņØĖņ×Éļź╝ ņäĀĒāØņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢśļŖö non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOAC)ļĪ£ ļČäļźśļÉ£ļŗż. NOACņØĆ direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), target-specific oral anticoagulant (TSOC) ļō▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ļÅä ļČłļ”░ļŗż. ĒŖĖļĪ¼ļ╣ł(thrombin)ņØä ņŻ╝ Ēæ£ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢśļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć(dabigatran)Ļ│╝ 10ļ▓ł ņØæĻ│ĀņØĖņ×É(Factor Xa)ļź╝ Ēæ£ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢśļŖö Xa ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØĖ ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś(rivaroxaban), ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś (apixaban) ļ░Å ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś(edoxaban) ļō▒ņØ┤ Ēśäņ×¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ņÖĆĒīīļ”░(warfarin)ņØĆ ļīĆĒæ£ņĀüņØĖ VKAļĪ£ ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ļŖö 36ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ļ®░ ļ╣ä ņŗ¼ņןņłśņłĀņØ┤ Ļ│äĒÜŹļÉ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ 5ņØ╝ ņĀä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[41]. Vitamin K ņØśņĪ┤ĒśĢ ņ×æņÜ® ĻĖ░ņĀäņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņĀĢļ¦źņŻ╝ņé¼ĒśĢ vitamin KĻ░Ć ņŚŁņĀäņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ļŗż. NOACņØś ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØ┤ 12-17ņŗ£Ļ░äņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Ćņן ĻĖĖĻ│Ā ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░śņØ┤ 5-9ņŗ£Ļ░äņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░Ćņן ņ¦¦ļŗż[42]. NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉļōżņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņÖĆ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņżæļŗ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ£ļŗż(Fig. 3). ņŗĀņןņ£╝ļĪ£ 80% ņØ┤ņāü ļ░░ņČ£ļÉśļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØĆ Ēü¼ļĀłņĢäĒŗ░ļŗī ņ▓Łņåīņ£© 50 mL/minļź╝ ĻĖ░ņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ļŗżļźĖ NOACņØĆ 30 mL/minļź╝ ĻĖ░ņżĆņ£╝ ļĪ£ ņżæļŗ© ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢ£ļŗż(Fig. 3) [41].

VKAļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢ£ļŗż. ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ international normalized ratio (INR) Ōēż 1.5ņØ┤ļ®┤ ņłśņłĀņØä ņĢłņĀäĒĢśĻ▓ī ņłśĒ¢ēĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[41,42]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĒśłņĀäņāēņĀäņ”ØņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ņĢäļלņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņŚÉņä£ VKAņØś ņżæļŗ©ņØĆ ņ£äĒŚśĒĢśļ®░ ļ╣äļČäĒÜŹ ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ (unfractionated heparin, UFH) ļśÉļŖö ņ╣śļŻī ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś ņĀĆļČäņ×Éļ¤ē ĒŚżĒīīļ”░(low molecular weight heparin, LMWH)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[43].

1. CHA2DS2-VASc ņĀÉņłśĻ░Ć 4ņĀÉ ņØ┤ņāüņØĖ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ

2. ĻĖ░Ļ│ä ņŗ¼ņןĒīÉļ¦ē, ņāłļĪ£ ņéĮņ×ģļÉ£ ņāØņ▓┤ ņŗ¼ņןĒīÉļ¦ē ņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×É

3. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ 3Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ļé┤ ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉņ×¼Ļ▒┤ņłĀņØä ļ░øņØĆ ĒÖśņ×É

4. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ 3Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ļé┤ ņĀĢļ¦źĒśłņĀäņāēņĀäņ”ØņØ┤ ļ░£ņāØĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×É

5. ĒśłņĀäņä▒Ē¢źņ”Ø(thrombophilia) ĒÖśņ×É

Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ĒśłņĀäņāēņĀäņ”Ø ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ĒĢśļŻ© 2ĒÜī ņ╣śļŻī ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś LMWH ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĻČīņןļÉśĻ│Ā ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļé«ņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ¦żņØ╝ 1ĒÜī ņśłļ░® ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[10,13]. LMWHņØś ļ¦łņ¦Ćļ¦ē ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØĆ ņłśņłĀ 12ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ņĀäņŚÉ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░ ņżæļō▒ļÅä ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņŗĀņן ĻĖ░ļŖź ņןņĢĀĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö Ēł¼ņŚ¼ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś ņĪ░ņĀĢņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[44]. VKA ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä 3-5ņØ╝Ļ░ä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļ®░ INR Ōēż 1.5ņŚÉ ļÅäļŗ¼ĒĢĀ ļĢīĻ╣īņ¦Ć ļ¦żņØ╝ INRņØä ņĖĪņĀĢĒĢśĻ│Ā, VKA ņżæļŗ© Ēøä 24ņŗ£Ļ░ä Ēøä ļśÉļŖö INR < 2.0ņØ┤ ļÉśļŖö ņ”ēņŗ£ LMWH ļśÉļŖö UFH ņÜöļ▓ĢņØä ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ļŗż[10,13].

VKAļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņāüļŗ╣Ē׳ ļåÆņ£╝ļ®░ ņ¦ĆĒśł Ļ│╝ņĀĢņŚÉļÅä ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣śĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉśļŖö ņłśņłĀņØ┤ļéś ņŗ£ņłĀņØś ņ£ĀĒśĢņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓Ģ ņĀüņÜ® ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ ĒīÉļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ņłśņłĀņØ╝ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ© ļ░Å LMWHļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīĻ│ĀļÉśļéś ļ░▒ļé┤ņן ļśÉļŖö Ļ▓Įļ»ĖĒĢ£ Ēö╝ļČĆ ņłśņłĀĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļé«ņØĆ ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ļŖö Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ļŗż[44]. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļÅä INRņØĆ ļé«ņØĆ ņ╣śļŻī ļ▓öņ£äļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ļ░öļ×īņ¦üĒĢśļŗż[44].

ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×Éļōż ņżæ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņłśĻ░Ć ņżæņ×¼ņŗ£ņłĀ ļśÉļŖö ņłśņłĀļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ┤ ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņØ╝ņŗ£ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņ£ĀĻ┤Ć ĒĢÖĒÜīļōżņØ┤ NOACņØś ņé¼ņÜ®Ļ│╝ ņżæļŗ©ņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ļ│äļÅäņØś Ēæ£ņżĆņ╣śļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[10,13,45]. ņłśņłĀ ņóģļźśņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļŗżļź┤ļ»ĆļĪ£ ņłśņłĀņØś ņóģļźś ļ░Å ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒(ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ļō▒)ņØä ņóģĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØś ņżæļŗ© ņŗ£ņĀÉņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[45]. NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉņØś ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ņĢĮņĀ£ ņĪ░ņĀĢņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ░£ņÜöļŖö ĻĘĖļ”╝ 3ņŚÉ ļéśĒāĆļé┤ņŚłļŗż.

ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ Ļ▓Įļ»ĖĒĢ£(minor bleeding risk) ņłśņłĀņØ┤ļéś ņŗ£ņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ņłśņłĀ ļśÉļŖö ņŗ£ņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[45]. ļ░£ņ╣ś, ņ╣śņŻ╝ņłśņłĀ, ļ░▒ļé┤ņןņØ┤ļéś ļģ╣ļé┤ņןņłśņłĀ, ņĪ░ņ¦üĻ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö ļé┤ņŗ£Ļ▓ĮĻ▓Ćņé¼ ļō▒ņØ┤ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ Ļ▓Įļ»ĖĒĢ£ ņłśņłĀņŚÉ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉ£ļŗż(Supplementary Table 3). ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņłśņłĀ ļ░Å ņŗ£ņłĀņØĆ ļ¦łņ¦Ćļ¦ē NOACņØä ļ│ĄņÜ® Ēøä 12-24 ņŗ£Ļ░ä ĒøäņŚÉ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ņ╣śļŻī Ēøä 6ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ĒĢśļ®┤ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņ×¼Ļ░£ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[45].

ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļé«ņØĆ(low bleeding risk) ņłśņłĀņØ┤ļéś ņŗ£ņłĀņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØ┤ ņĀĢņāüņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö 24ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀäņŚÉ NOACņØä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņŗĀņןĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ņØ┤ņāüņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņØ┤ļ│┤ļŗż ļŹö ņØ┤ļźĖ ņŗ£Ļ░ä(48ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀä)ņŚÉ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗļŗż[45]. ņĪ░ņ¦üĻ▓Ćņé¼ļź╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢśļŖö ļé┤ņŗ£Ļ▓Į ņŗ£ņłĀ, ņĀäļ”ĮņäĀņØ┤ļéś ļ░®Ļ┤æ ņĪ░ņ¦üĻ▓Ćņé¼, ļ░ĢļÅÖĻĖ░ Ēś╣ņØĆ ICD ņéĮņ×ģņłĀ ļō▒ņØ┤ ņØ┤ņŚÉ ņåŹĒĢ£ļŗż(Supplementary Table 3; Fig. 3) [45].

ļ¦łņ¦Ćļ¦ēņ£╝ļĪ£, ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ(high bleeding risk) ņŗ£ņłĀņØ┤ļéś ņłśņłĀņØä ņ¦äĒ¢ēĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņłśņłĀ 48ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀäņŚÉ NOAC ņżæļŗ©ņØä ņČöņ▓£ĒĢśļ®░ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØä ņé¼ņÜ® ņżæņØĖ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņןņĢĀ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö 48ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ņāü NOACņØä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś ļ│ĄĻ░Ģ ļé┤ ņłśņłĀ, ĒØēĻ░Ģ ļé┤ ņłśņłĀ, ņ▓ÖņČö ļ¦łņĘ© ĒĢś ņŗ£ņłĀ ļō▒ņØ┤ ņØ┤ņŚÉ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉ£ļŗż(Supplementary Table 3) [45]. NOACņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņŚÉĻ▓īļŖö ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØĆ ņČöņ▓£ļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż. ņØ┤ļŖö NOACņØś ņśłņĖĪ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņĢĮļĀźĒĢÖņĀü ĒŖ╣ņä▒, ņ¦¦ņØĆ ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ ļ░Å ļ╣ĀļźĖ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀĒÜ©Ļ│╝ ņŚŁņĀä ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļō▒ņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż. NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņ×ÉļōżņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēļÉ£ ņ×äņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØĆ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļ¦ī ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé¼ ļ┐É ĒśłņĀä ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØĆ ņżäņØ┤ņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśņśĆļŗż[46].

ņłśņłĀ Ēøä VKAļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņÜöļ▓ĢņØś ņ×¼Ļ░£ Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØĆ ļŗżņØīĻ│╝ Ļ░Öļŗż. LMWH ļśÉļŖö UFHļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņ¦ĆĒśł ņāüĒā£ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņłśņłĀ Ēøä 1-2ņØ╝ ĒøäņŚÉ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŹś ņÜ®ļ¤ēņ£╝ļĪ£ ļŗżņŗ£ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢ£ļŗż. VKA ļŖö ņ▓śņØī 2ņØ╝ ļÅÖņĢłņØĆ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņ£Āņ¦Ć ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś 1.5ļ░░ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ Ēøä ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņ£Āņ¦Ć ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. INRņØ┤ ņ╣śļŻī ņłśņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÜīļ│ĄļÉĀ ļĢīĻ╣īņ¦Ć LMWH ļśÉļŖö UFHļź╝ Ļ│äņåŹ ļ│æņÜ® Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņłśņłĀ Ēøä ņÖäņĀäĒĢ£ ņ¦ĆĒśłņØ┤ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĪīļŗżļ®┤ NOACņØĆ ņŗ£ņłĀ Ēøä 6-8ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤Ēøä ņé¼ņÜ® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņØ╝ļČĆ ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņłśņłĀ ņØ┤Ēøä 48-72ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ NOACņØä ņ×¼Ļ░£ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņāüņŖ╣ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ ļ¦łļ╣äņä▒ ņןĒÅÉņćä ļō▒ņØś ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”Øņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ņĢĮņĀ£ Ēł¼ņŚ¼Ļ░Ć ļČłĻ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļÅä ļ░£ņāØĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņāüĒÖ®ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ ļō▒ņØś ļ╣äĻ▓ĮĻĄ¼ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ ņśłļ░®ņÜöļ▓ĢņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ ĒøäņŚÉ NOACņØä ļŗżņŗ£ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ░ü ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│äļĪ£ ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ņĢĮņĀ£ ņżæļŗ© ņŗ£ņĀÉĻ│╝ ņ×¼Ļ░£ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØĆ Fig. 4ņŚÉ ļéśĒāĆļé┤ ņŚłļŗż[45].

ņłś ļČäļé┤ņŚÉ ņłśņłĀņØś Ļ▓░ņĀĢņØ┤ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĀĖņĢ╝ ĒĢśļŖö ņ”ēĻ░üņłśņłĀ(ņśł, ņ”ēĻ░üņĀüņØĖ ņāØļ¬ģ/ņé¼ņ¦Ć/ņןĻĖ░ļź╝ ĻĄ¼ĒĢśļŖö ņłśņłĀ, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņŗ¼ņן/ĒśłĻ┤Ć/ņŗĀĻ▓Į ņÖĖĻ│╝ņĀü ņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀ)ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņåīņŗżļÉĀ ļĢīĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņłśņłĀņØä ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢĀ ņłś ņŚåļŗż. ņżæļō▒ļÅä-ņżæņ”ØņØś ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö ņłśņłĀņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņłśņłĀ ņĀä ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś ņŚŁņĀäņĀ£ņØĖ ņØ┤ļŗżļŻ©ņŗ£ņŻ╝ļ¦Ö (idarucizumab)ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[47]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, Xa ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØś ņŚŁņĀäņĀ£ņØĖ ņĢłļŹ▒ņé¼ļäżņØ┤ĒŖĖ-ņĢīĒīī(andexanate-╬▒)ļŖö ņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ĒÜ©ņÜ®ņä▒ņØ┤ ĒÖĢļ”ĮļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņ£╝ļ®░, ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņØ┤ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņĢäņ¦ü ņ×äņāüņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņŚåļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņÖĆ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ļŖö ļČĆņĪ▒ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļ╣äĒŖ╣ņØ┤ņĀü ņØæĻ│ĀņØĖņ×É ļåŹņČĢļ¼╝(prothrombin complex concentrate, PCC) Ēł¼ņŚ¼ļź╝ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ļ│╝ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļéś ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉļŖö Ēśäņ×¼ PCCĻ░Ć ĒŚłĻ░ĆļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņŚåļŗż[45].

ņłśņłĀņØ┤ Ļ▓░ņĀĢļÉ£ Ēøä ņłś ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉ ņŗżĒ¢ēņØ┤ ņÜöĻĄ¼ļÉśļŖö ĻĖ┤ĻĖē ņłśņłĀ(ņśł, ņ×Āņ×¼ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØļ¬ģņØä ņ£äĒśæĒĢśļŖö ņāüĒā£ņØś ĻĖēņä▒ ļ░£ļ│æ ļśÉļŖö ņ×äņāüņĀü ņĢģĒÖöņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ņżæņ×¼ņĀü ņłśņłĀ, ņé¼ņ¦Ć/ņןĻĖ░ņØś ņāØņĪ┤ ļ░Å Ļ│©ņĀłņØś ĻĄÉņĀĢ, ĒåĄņ”Ø ņÖäĒÖö ļśÉļŖö ĻĖ░ĒāĆ ņ”ØņāüņØä ņ£äĒśæĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņāüĒā£)ņØĆ ņłśņłĀ ļśÉļŖö ņŗ£ņłĀņØä ņĀüņ¢┤ļÅä 12ņŗ£Ļ░ä(Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗżļ®┤ ļ¦łņ¦Ćļ¦ē NOAC Ēł¼ņŚ¼ Ēøä 24ņŗ£Ļ░ä) ņĀĢļÅä ņŚ░ĻĖ░ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīņןļÉ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, ņŚŁņĀäņĀ£ ļśÉļŖö PCCņØś ņé¼ņÜ® ņŚ¼ļČĆļź╝ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒśłņĢĪņØæĻ│Ā Ļ▓Ćņé¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝(prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT], anti-FXa assay, diluted thrombin time [dTT] ļō▒)ļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢ┤ ļæÉļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņóŗļŗż[45].

ņłśņłĀ Ļ▓░ņĀĢ Ēøä ņłśņØ╝ ļé┤ņŚÉ ņŗżĒ¢ēņØ┤ ņÜöĻĄ¼ļÉśļŖö ņŗĀņåŹņłśņłĀ(ņāØļ¬ģ/ņé¼ņ¦Ć/ņןĻĖ░ ņāØņĪ┤ņŚÉ ņ£äĒśæņØ┤ ļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö ņĪ░ĻĖ░ ņ╣śļŻīĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░)ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ NOACņØś ņżæļŗ© ņŚ¼ļČĆļŖö ļ╣äņØæĻĖēņłśņłĀņØś ĻĖ░ņżĆņØä ļö░ļźĖļŗż[45].

ņłśņłĀ ļ░Å ņŗ£ņłĀ ņŗ£ ĒĢŁĒśłņĀäņĀ£ņØś ņĪ░ņĀłņØĆ ņłśņłĀņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņÖĆ ņłśņłĀ ņĀäĒøä ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļź╝ ņóģĒĢ®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś ņłśņłĀ ļ░Å ņŗ£ņłĀ ņŗ£Ē¢ē ņŗ£ ņĢäņŖżĒö╝ļ”░ņØĆ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņøÉņ╣ÖņØ┤ļŗż. DAPTļź╝ ņżæļŗ©ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĒśłņĀä ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ ņłśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĀĢļ¦źņŻ╝ņé¼ĒśĢ ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ░ĆĻĄÉņÜöļ▓ĢņØä ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. VKAļŖö ņłśņłĀ 5ņØ╝ ņĀä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░ NOACņØĆ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņłśņłĀ 24-48ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņøÉņ╣ÖņØ┤ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņāüĻĖ░ ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØĆ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ Ļ┤ĆļĀ© ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ĒÖĢļ”ĮļÉ£ Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņĢäļŗłļ»ĆļĪ£ Ē¢źĒøä ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ┤ ĒåĄņØ╝ļÉ£ ņ╣śļŻīņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØä ļ¦łļĀ©ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ£ ļģĖļĀźņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary┬ĀTable┬Ā2.

Interventional or surgical procedures that should be accompanied by aspirin discontinuation in patients at low thrombotic riska

Supplementary┬ĀTable┬Ā3.

Classification of surgeries/interventions in terms of bleeding risk

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YP and ESS, as a first author and a corresponding author, contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. HKK and JYM wrote drafts of the antiplatelet section and the anticoagulant section respectively. YBS drew figures. All other authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The document has achieved endorsement and consent from the clinical practice guideline committee of the Korean Society of Cardiology consisting of the deputies from the Korean Society of Cardiology, the Korean Society of Hypertension, the Korean Heart Rhythm Society, the Korean Society of Heart Failure, the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology, the Korean Association of Clinical Cardiology, the Korean Society of Cardiometabolic Syndrome, the Korean Society of Echocardiography, and the Korean Society of lipid and atherosclerosis.

REFERENCES

1. Tokushige A, Shiomi H, Morimoto T, et al. Incidence and outcome of surgical procedures after coronary bare-metal and drug-eluting stent implantation: a report from the CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort-2. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:237ŌĆō246.

2. Capodanno D, Angiolillo DJ. Management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease requiring cardiac and noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2013;128:2785ŌĆō2798.

3. Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2667ŌĆō2674.

4. Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative acute myocardial infarction associated with non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2409ŌĆō2417.

5. Rossini R, Angiolillo DJ, Musumeci G, et al. Antiplatelet therapy and outcome in patients undergoing surgery following coronary stenting: Results of the surgery after stenting registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017;89:E13ŌĆōE25.

6. Egholm G, Kristensen SD, Thim T, et al. Risk associated with surgery within 12 months after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:2622ŌĆō2632.

7. Rajagopalan S, Ford I, Bachoo P, et al. Platelet activation, myocardial ischemic events and postoperative non-response to aspirin in patients undergoing major vascular surgery. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:2028ŌĆō2035.

8. Priebe HJ. Triggers of perioperative myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Br J Anaesth 2004;93:9ŌĆō20.

9. Oprea AD, Popescu WM. Perioperative management of antiplatelet therapy. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(Suppl 1):i3ŌĆōi17.

10. Rossini R, Tarantini G, Musumeci G, et al. A multidisciplinary approach on the perioperative antithrombotic management of patients with coronary stents undergoing surgery: surgery after stenting 2. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:417ŌĆō434.

11. Stawiarski K, Kataria R, Bravo CA, et al. Dual-antiplatelet therapy guidelines and implications for perioperative management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018;32:1072ŌĆō1080.

12. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/ AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation 2016;134:e123ŌĆōe155.

13. Rossini R, Musumeci G, Visconti LO, et al. Perioperative management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary stents undergoing cardiac and non-cardiac surgery: a consensus document from Italian cardiological, surgical and anaesthesiological societies. EuroIntervention 2014;10:38ŌĆō46.

14. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2018;39:213ŌĆō260.

15. Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. JAMA 2013;310:1462ŌĆō1472.

16. Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1494ŌĆō1503.

17. Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:237ŌĆō244.

18. Oscarsson A, Gupta A, Fredrikson M, et al. To continue or discontinue aspirin in the perioperative period: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2010;104:305ŌĆō312.

19. Rossini R, Musumeci G, Capodanno D, et al. Perioperative management of oral antiplatelet therapy and clinical outcomes in coronary stent patients undergoing surgery. Results of a multicentre registry. Thromb Haemost 2015;113:272ŌĆō282.

20. Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JR, et al. The incidence and timing of noncardiac surgery after cardiac stent implantation. J Am Coll Surg 2012;214:658ŌĆō667.

21. Mehran R, Baber U, Steg PG, et al. Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PARIS): 2 year results from a prospective observational study. Lancet 2013;382:1714ŌĆō1722.

22. Wilson SH, Fasseas P, Orford JL, et al. Clinical outcome of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in the two months following coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:234ŌĆō240.

23. Cruden NL, Harding SA, Flapan AD, et al. Previous coronary stent implantation and cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3:236ŌĆō242.

24. Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, R├╝cker G. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention - cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation - review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med 2005;257:399ŌĆō414.

25. Colombo A, Chieffo A, Frasheri A, et al. Second-generation drug-eluting stent implantation followed by 6- versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy: the SECURITY randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2086ŌĆō2097.

26. Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Park KW, et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents: the efficacy of xience/promus versus cypher to reduce late loss after stenting (EXCELLENT) randomized, multicenter study. Circulation 2012;125:505ŌĆō513.

27. Feres F, Costa RA, Abizaid A, et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents: the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:2510ŌĆō2522.

28. Wijeysundera DN, Wijeysundera HC, Yun L, et al. Risk of elective major noncardiac surgery after coronary stent insertion: a population-based study. Circulation 2012;126:1355ŌĆō1362.

29. Holcomb CN, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Maddox TM, Hawn MT. The incremental risk of coronary stents on postoperative adverse events: a matched cohort study. Ann Surg 2016;263:924ŌĆō930.

30. Giustino G, Chieffo A, Palmerini T, et al. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy after complex PCI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1851ŌĆō1864.

31. Subherwal S, Bach RG, Chen AY, et al. Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) bleeding score. Circulation 2009;119:1873ŌĆō1882.

32. Mehran R, Pocock SJ, Nikolsky E, et al. A risk score to predict bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2556ŌĆō2566.

33. Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093ŌĆō1100.

34. Capodanno D, Musumeci G, Lettieri C, et al. Impact of bridging with perioperative low-molecular-weight heparin on cardiac and bleeding outcomes of stented patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Thromb Haemost 2015;114:423ŌĆō431.

35. Angiolillo DJ, Firstenberg MS, Price MJ, et al. Bridging antiplatelet therapy with cangrelor in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;307:265ŌĆō274.

36. Angiolillo DJ, Rollini F, Storey RF, et al. International expert consensus on switching platelet P2Y12 receptor-inhibiting therapies. Circulation 2017;136:1955ŌĆō1975.

37. Banerjee S, Angiolillo DJ, Boden WE, et al. Use of antiplatelet therapy/DAPT for post-PCI patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1861ŌĆō1870.

38. Hong SJ, Kim MJ, Kim JS, et al. Effect of perioperative antiplatelet therapy on outcomes in patients with drug-eluting stents undergoing elective noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:1414ŌĆō1421.

39. Kim BK, Yoon JH, Shin DH, et al. Prospective and systematic analysis of unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures during the first year after drug-eluting stent implantation. Yonsei Med J 2014;55:345ŌĆō352.

40. Kim C, Kim JS, Kim H, et al. Patterns of antiplatelet therapy during noncardiac surgery in patients with second-generation drug-eluting stents. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016218.

41. Keeling D, Tait RC, Watson H; British Committee of Standards for Haematology. Peri-operative management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. Br J Haematol 2016;175:602ŌĆō613.

42. Raval AN, Cigarroa JE, Chung MK, et al. Management of patients on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in the acute care and periprocedural setting: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e604ŌĆōe633.

43. Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, et al. 2014 ESC/ESA guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: the joint task force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2383ŌĆō2431.

44. Pengo V, Cucchini U, Denas G, et al. Standardized low-molecular-weight heparin bridging regimen in outpatients on oral anticoagulants undergoing invasive procedure or surgery: an inception cohort management study. Circulation 2009;119:2920ŌĆō2927.

45. Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1330ŌĆō1393.

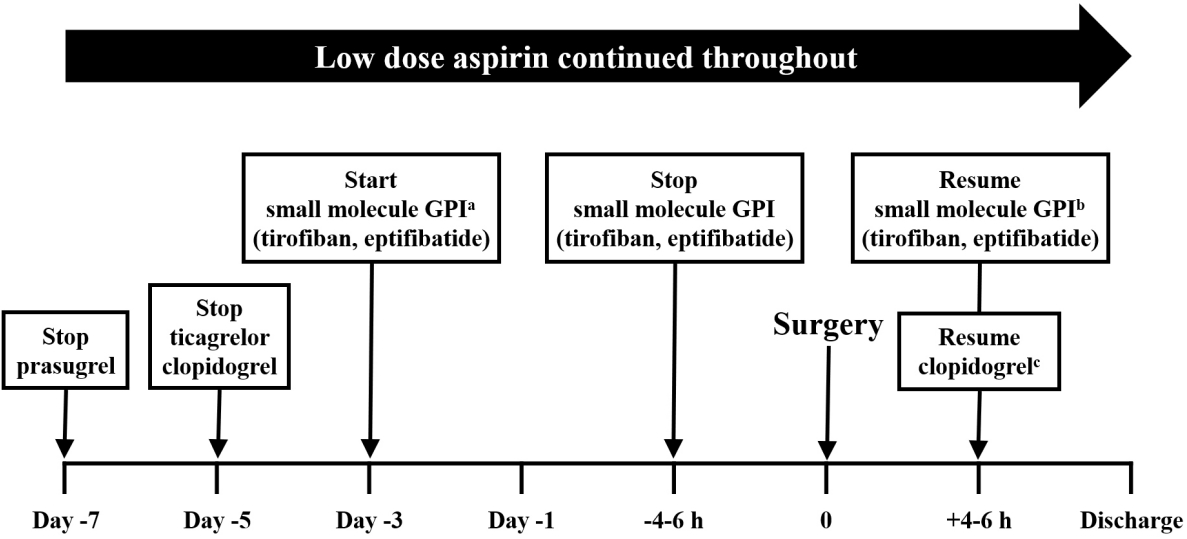

Bridging antiplatelet agent therapy [2]. Clopidogrel and ticagrelor should be discontinued for 5 days and prasugrel for 7 days. Bridging with tirofiban or eptifibatide using a maintenance-dose regimen (no bolus) should be initiated 72 hours before surgery and continued for 4-6 hours after surgery. In patients with renal impairment, a dose reduction is warranted and earlier suspension (8-12 hours) should be considered. After surgery, clopidogrel (not prasugrel or ticagrelor) should be resumed (a loading dose) as soon as oral administration is possible and the risk of severe bleeding is under control. If an oral P2Y12 inhibitor is inappropriate, post-surgery bridging might be considered. GPI, glycoprotein IIb or IIIa inhibitor. aTirofiban: 0.1 ╬╝g/kg/min; if the creatinine clearance is < 50 mL/min, adjust to 0.05 ╬╝g/kg/min. Eptifibatide: 2.0 ╬╝g/kg/min; if the creatinine clearance is < 50 mL/min, adjust to 1.0 ╬╝g/kg/min. bIf oral administration is not possible; cA 300-600 mg loading dose as soon as oral administration is possible. Neither prasugrel nor ticagrelor is recommended.

Figure┬Ā1.

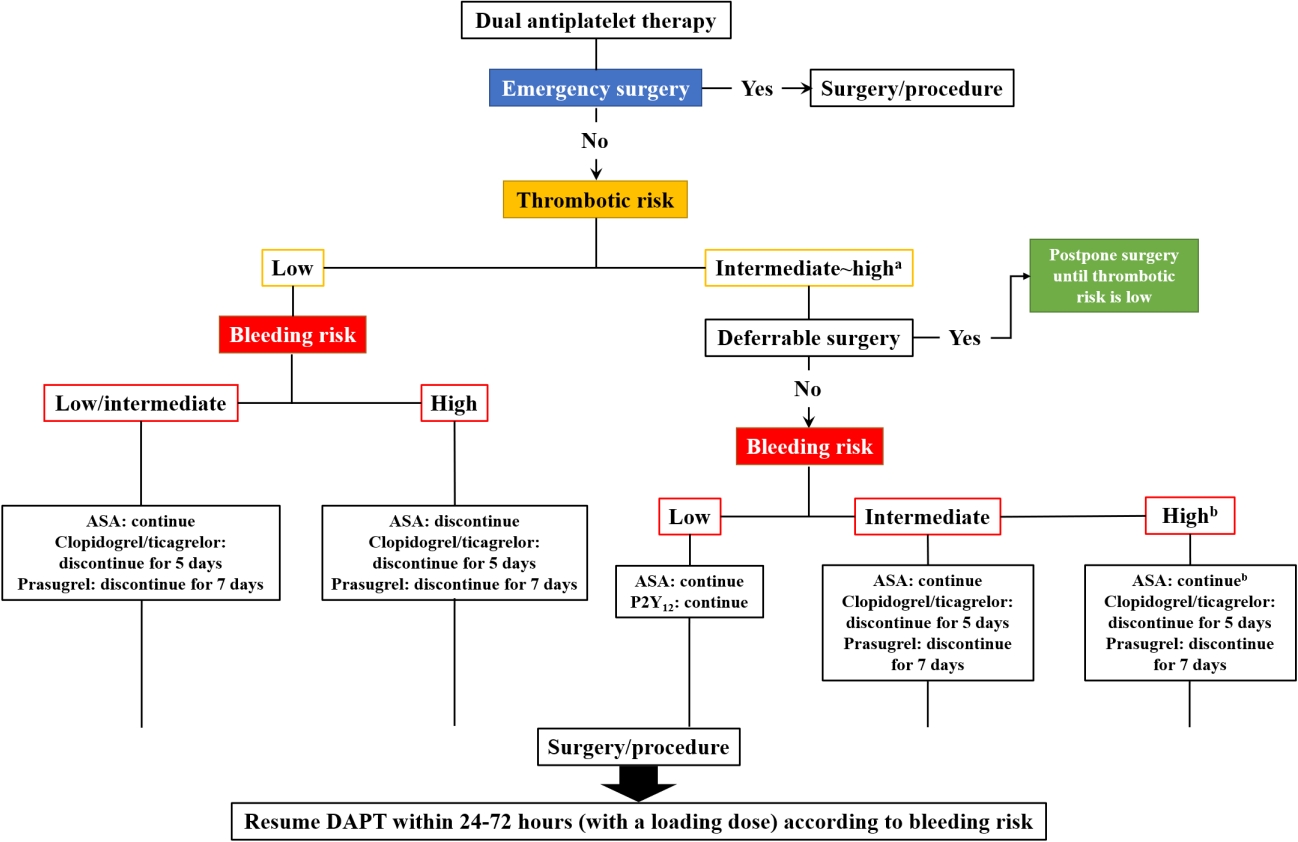

Perioperative management of dual antiplatelet therapy. ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; DAPT, dual antithrombotic therapy. aConsider bridge therapy; bContinue unless contraindicated.

Figure┬Ā2.

Perioperative management of oral anticoagulants. VKA, vitamin K antagonist; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist (oral anticoagulants); INR, international normalized ratio.

Figure┬Ā3.

Cessation and re-initiation of non-vitamin K antagonist, oral anticoagulant therapy in patients undergoing elective surgery [43]. aCreatinine clearance Ōēź 30 mL/min; bCreatinine clearance Ōēź 30 mL/min; cHighest-risk neurosurgery/cardiac surgery, severe renal insufficiency, and a combination of factors predisposing to higher, non-vitamin K antagonist, oral anticoagulant levels.

Figure┬Ā4.

Table┬Ā1.

Clinical and angiographic features associated with thrombotic risk [10]

Table┬Ā2.

Thrombotic risk by the timing of elective surgery [10]

|

Clinical or angiographic risk factors (+)a |

Clinical or angiographic risk factors (-)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POBA | BMS | 2G DES | BVS | POBA | BMS | 2G DES | BVS | |

| < 1 month | High | High | High | High | High (< 2 weeks)/intermediate | High | High | High |

| 1-3 months | Intermediate | High | High | High | Low | Intermediate | Intermediate | High |

| 3-6 months | Intermediate | High | High | High | Low | Low/intermediate | Low/intermediate | High |

| 6-12 months | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | High | Low | Low | Low | High |

| > 12 months | Low | Low | Low | UD | Low | Low | Low | UD |

Table┬Ā3.

General principles to be considered when discontinuing antiplatelet therapy during the perioperative period [10]

| Bleeding risk | Antithrombotics |

Thrombotic risk |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | ||

| Low | ASA | Continue | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone |

| Nondeferrable surgery: continue | Nondeferrable surgery: continue | |||

| P2Y12 inhibitor | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone | |

| Resume within 24-72 hours (with a LD) | Nondeferrable surgery: continue | Nondeferrable surgery: continue | ||

| NOAC | Discontinue at least 24-96 hours beforeb; Resume within 48-72 hoursc | |||

| Intermediate | ASA | Continue | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone |

| Nondeferrable surgery: continue | Nondeferrable surgery: continue | |||

| P2Y12 inhibitor | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone | |

| Nondeferrable surgery: | Nondeferrable surgery: | |||

| Resume within 24-72 hours (with a LD) | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | ||

| Resume within 24-72 hours (with a LD) | Resume within 24-72 hoursa (with a LD) | |||

| Consider bridge therapy | ||||

| NOAC | Discontinue at least 24-96 hours beforeb; Resume within 48-72 hoursc | |||

| High | ASA | Discontinue | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone |

| Nondeferrable surgery: continue | Nondeferrable surgery: continue | |||

| P2Y12 inhibitor | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | Elective surgery: postpone | Elective surgery: postpone | |

| Nondeferrable surgery: | Nondeferrable surgery: | |||

| Resume within 24-72 hours (with a LD) | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | Discontinue 5 days before for clopidogrel/ticagrelor, 7 days before for prasugrel | ||

| Resume within 24-72 hours (with a LD) | Resume within 24-72 hoursa (with a LD) | |||

| Consider bridge therapy | ||||

| NOAC | Discontinue at least 24-96 hours beforeb; Resume within 48-72 hoursc | |||

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print