INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the general population. The different structures of the heart, including the interatrial septum and left atrial appendage (LAA), are sites of ischemic stroke or cardioembolism [1]. Although rare, foreign bodies can reach the heart and cause serious complications, including embolic cerebral infarction. They can be removed surgically or percutaneously or managed conservatively [2]. Here, we report a case of recurrent acute stroke in a patient with atrial fibrillation (AF), a patent foramen ovale (PFO), and a foreign body in the right heart chambers.

CASE REPORT

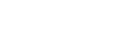

A 68-year-old man was admitted to Neurology Clinic at Severance Hospital because of recurrent stroke. His medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hyperthyroidism. He had undergone a partial gastrectomy for peptic ulcer perforation approximately 30 years previously. One day before admission, he had developed sudden dysarthria and right-sided weakness. He was diagnosed with acute left middle cerebral artery infarction based on magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (Fig. 1A) and referred to the cardiology department for evaluation of the cardiac embolic source of the acute stroke.

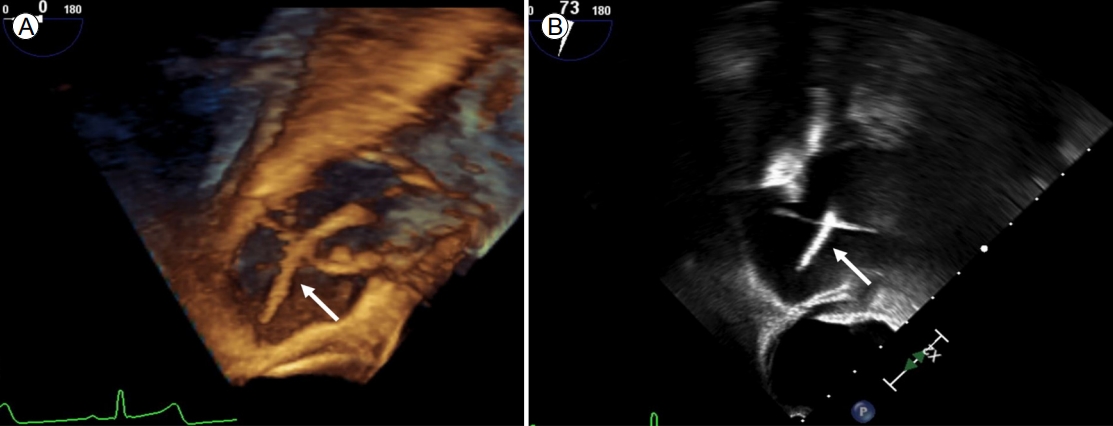

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed linear echogenic material measuring approximately 9.2 cm and spanning from the right ventricular apex to the interatrial septum in the right atrium (Fig. 1B). No spontaneous echo contrast or thrombus was observed in the left atrium or LAA. However, a left-to-right shunt via the PFO with no high-risk features was detected (slit length, 8 mm; slit diameter, 1.6 mm). TEE revealed an LAA ostial diameter of 18 mm, a maximum landing zone width of 15 mm, and a depth of 25 mm. He developed mild tricuspid regurgitation, without pulmonary hypertension or other relevant features. These findings were confirmed by thoracic computed tomography (Fig. 1C).

Suspecting cardioembolic infarction without hemorrhagic transformation, we started anticoagulant therapy. However, despite administering warfarin at a therapeutic dose, the patient experienced a third acute stroke. In addition, while the patient was hospitalized to evaluate the cardiac embolic source, an electrocardiogram showed paroxysmal AF (CHA2DS2-VASc: 5). We discussed the case at a brain-heart team meeting with a neurologist, interventional cardiologist, imaging cardiologist, and radiologist. We decided to perform surgical or percutaneous closure of the PFO and simultaneous LAA occlusion and foreign body removal. When this decision was communicated to the patient and his family, they strongly preferred the percutaneous procedures. Therefore, the patient was transferred to the cardiology department for interventional treatment.

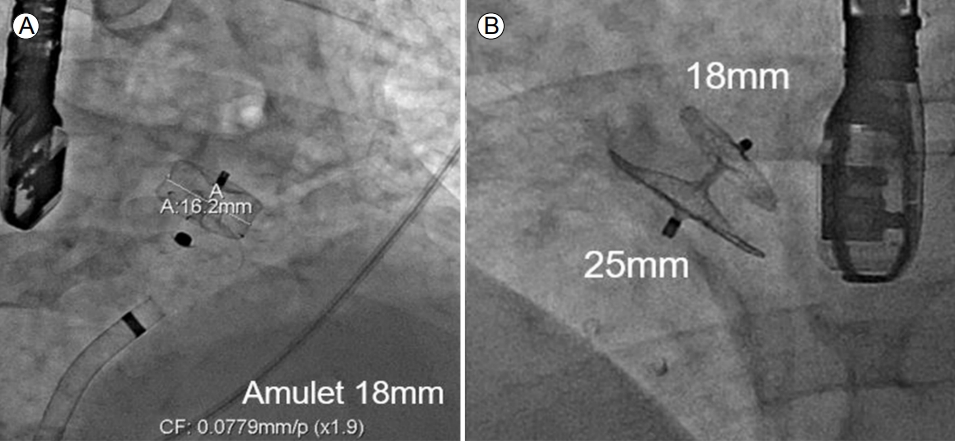

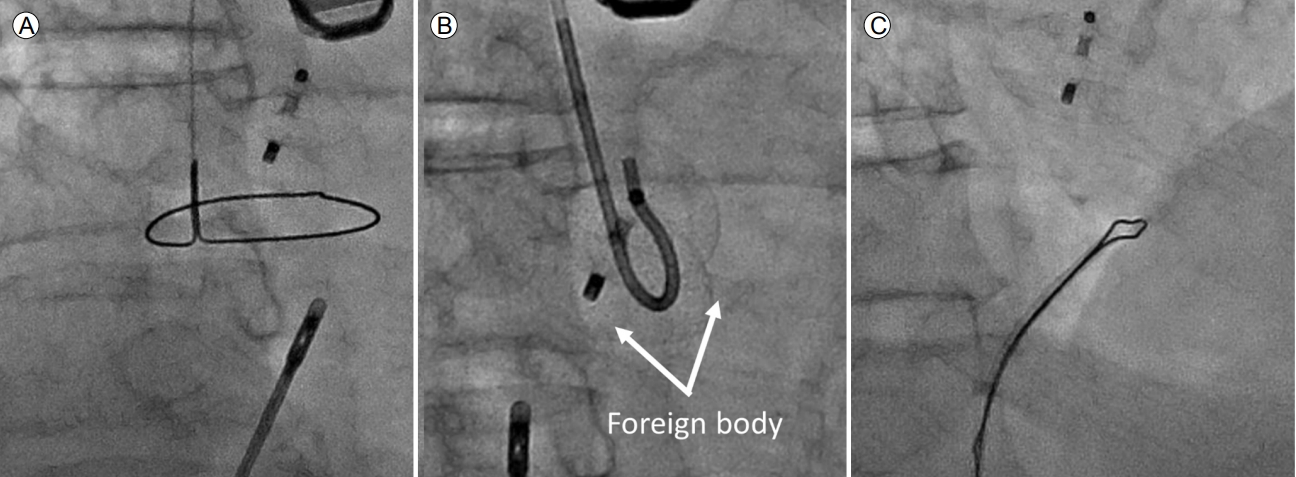

First, LAA occlusion was performed via the right femoral vein using TEE and fluoroscopic guidance under general anesthesia. A transseptal approach was used via the PFO with an 8.5 Fr Swartz trans-septal catheter and a dilator. After placing the catheter in the LAA, contrast was injected via the sheath to demonstrate the anatomy and size of the LAA. An amulet device (AMPLATZER Ōäó amulet 18 mm, Abbott, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was deployed, and a stable position was confirmed angiographically by the tug test, while TEE showed no leakage (Fig. 2A). Then the catheter was replaced with a 13 Fr AMPLATZER TorqVue delivery sheath (St. Jude Medical, Plymouth, MN, USA), and the PFO occlusion device (AMPLATZERŌäó PFO Occluder 25/18 mm, Abbott) was deployed successfully (Fig. 2B). Stability and complete occlusion were confirmed by an intraprocedural TEE. Finally, we attempted to capture the distal end of the foreign body using a snare, although it could not be clearly visualized under fluoroscopy. Initially, a forceps-assisted device was used; however, despite several attempts, the distal end of the foreign body could not be grasped (Fig. 3A, B). Subsequently, we decided to use an OmniŌäó catheter via the right jugular vein. On opening the OmniŌäó catheter with wire advancement, we captured and retrieved the middle portion of the foreign body (Fig. 3C). The foreign body in the right cardiac chamber was repositioned using 3D TEE (Fig. 4). The multipurpose catheter was re-released using a 30 mm snare and recaptured at a distal end. The piece was straightened and easily extracted from the femoral vein sheath along with the foreign body, which appeared to be the tip of a rubber-enclosed intravenous line (Fig. 5) with several, tiny, easily broken particles. The procedure was terminated without complications.

DISCUSSION

Up to 58% of patients with cryptogenic stroke have a right-to-left cardiac shunt or PFO [3,4]. Although the cause of recurrent acute stroke was unclear in our case, it may have resulted from embolization of particles from the foreign body via the PFO. Another potential cause was AF because the patient had a high CHA2DS2-VASc score, which implies an increased risk for stroke [4]. When the patient had a third stroke, the prognosis was poor. Therefore, we attempted to eliminate the possible causes of stroke. We decided to perform LAA occlusion via the PFO, followed by PFO closure and foreign body removal. The patient had an anatomy that allowed LAA occlusion via the PFO [5].

The unique feature of this case was the difficulty of catheter withdrawal, in the initial approach, from the right cardiac chambers because the foreign body was not visualized in fluoroscopy. The foreign body was removed successfully using an OmniŌäó catheter, which allowed slight pull-back of the foreign body with subsequent distal-end exposure and the final retrieval using the snaring technique [6]. Antecedent piece repositioning using the OmniŌäó catheter before snaring, particularly when the tip of the foreign body is not free, has been described with a high technical success rate [6]. The foreign body could be easily pulled back with the OmniŌäó catheter, and its distal end could be turned sufficiently to be snared in a second maneuver.

In conclusion, we report a rare case of recurrent stroke caused by a right-chamber foreign body. We successfully retrieved the foreign body percutaneously and occluded the LAA and PFO.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print