|

|

| Korean J Med > Volume 95(3); 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis is a common respiratory disease that is frequently encountered in daily practice. However, it has been regarded as an orphan lung disease and had been often neglected by the physicians. Fortunately, recent studies have unveiled many important clinical aspects of bronchiectasis. Accordingly, international evidence-based practice guideline such as the European Respiratory Society guideline and the British Thoracic Society (BTS) guideline have been published recently. However, as there is no domestic evidence-based guideline, we introduce clinical approaches to diagnose bronchiectasis and discuss important aspects of bronchiectasis based on most recently published the BTS guideline. In addition, we cover the treatment of bronchiectasis based on the BTS guideline. We hope newly assembled a Korean bronchiectasis study group, name the Korean Multicenter Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (KMBARC) would contribute to publishing Korean bronchiectasis guideline, soon.

비낭포성 섬유증 기관지확장증(non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, 이하 기관지확장증)은 흉부 영상 검사에서 기관지 확장이 관찰되는 질환으로 기침, 객담, 호흡곤란, 반복적인 호흡기 감염이 특징적으로 나타난다[1]. 기관지확장증의 유병률은 지역, 인종, 연구 방법에 따라 매우 다양하게 보고되어 왔지만, 전 세계적으로 증가하고 있는 추세이다[2]. 최근 Choi 등이 시행한 연구에 의하면 국내 기관지확장증의 유병률은 인구 10만 명당 464명으로 유럽이나 미국보다 높은 편이다[3-7]. 유병률이 높은 만큼 국내 기관지확장증의 질병 부담 역시 유럽이나 미국보다 높을 것으로 예상된다.

기관지확장증은 임상의사가 외래에서 흔히 접하는 질환이지만 최근까지 의사들의 관심을 많이 받지 못하는 질환이었다[8]. 하지만 최근 기관지확장증에 대한 국제적 관심이 높아지면서 유럽을 중심으로 활발한 임상 연구가 이루어졌고, 기관지확장증의 진단과 치료에 비약적인 발전이 있었다[9]. 이를 바탕으로 2017년에는 유럽호흡기학회(European Respiratory Society)에서 성인 기관지확장증 진료지침(European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis) [1]을 발간하였으며, 2019년에는 영국흉부학회(British Thoracic Society)에서 성인 기관지확장증 진료지침(British Thoracic Society Guideline for bronchiectasis in adults) [10]을 발간하였다. 안타깝게도 한국 기관지확장증 진료지침은 현재 존재하지 않기 때문에, 가장 최근에 발간된 영국흉부학회 성인 기관지확장증 진료지침을 중심으로 기관지확장증의 임상 접근법을 기술하려고 한다.

기관지확장증의 진단을 위해서는 해부학적으로 기관지의 비정상적인 확장을 증명해야 하며, 기저 기관지확장증의 심한 정도를 파악해야 하기 때문에 기관지확장증이 의심되는 환자에서는 흉부 X선 검사와 흉부 전산화단층촬영(computed tomography, CT)을 시행할 것이 권고된다. 특히 기저 영상 검사는 임상적으로 안정적일 때 시행할 것을 권고하고 있는데, 이는 향후 비교하는 것이 중요하기 때문이다.

기관지확장증의 진단을 위한 전산화단층촬영으로는 고해상 전산화단층촬영(high resolution CT) 뿐만 아니라 체적화 전산화단층촬영(volumetric CT)도 가능하며, 후자를 사용할 경우에는 방사선 용량 감소 기술을 사용할 것을 권고한다. 고해상 전산화단층촬영에 비해 체적화 전산화단층촬영이 기 관지확장증 진단의 감수성(sensitivity)이 높고, 판독자 간 판독 일치율이 높은 것으로 알려져 있다[11,12]. 기관지확장증의 진단을 위한 전산화단층촬영 프로토콜은 표 1과 같다[10].

기관지확장증은 전산화단층촬영에서 기관지의 확장이 관찰되는 것으로 정의되는데, 기관지확장은 다음 3가지 중 1가지 이상으로 정의한다: 1) 기관지와 동맥의 비(안쪽 기관지 내경과 동반하는 폐동맥의 비, bronchoarterial ratio, BAR > 1), 2) 기관지 내경의 점진적 감소가 없는 경우(lack of tapering), 3) 벽측 흉막 1 cm 이내에 기도가 보이거나 또는 종격동 흉막에 기도가 닿는 경우. 하지만 기관지확장증을 진단할 때 BAR > 1이라는 기준을 일률적으로 적용하기는 어렵다는 주장도 있는데, 이는 BAR이 연령과 상관관계가 있기 때문이다. 예로 18세 미만에서는 BAR이 0.8 이상인 경우 임상적으로 기관지확장증 진단이 더 적절하였다는 보고가 있는 반면[13], 65세 이상의 성인에서는 45%가 BAR > 1이었다는 보고도 있다[14]. 이외에도 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)은 폐동맥 수축으로 인한 폐동맥 내경의 감소로 인해 BAR이 증가할 수 있다[15].

기관지확장증은 만성적으로 점액농성(mucopurulent) 또는 화농성(purulent) 객담을 호소하는 환자, 특히 기관지확장증의 위험인자를 가진 경우에 기관지확장증을 의심해야 한다. 기관 지확장증의 여러 위험인자 중 특히 중요한 것은 동반 질환이다. 기관지확장증에 동반될 수 있는 대표적인 폐 외 질환은 만성 부비동염(chronic rhinosinusitis) [16], 결체조직 질환(connective tissue disease) [17,18], 염증성 장질환(inflammatory bowel disease) [19], 인간면역결핍바이러스(human immunodeficiency virus 1) 감염[20,21], 고형 장기 및 골수이식, 림프종과 혈관염 등을 치료하기 위해 면역억제제를 사용한 경우[22] 등이 있고, 폐질환으로는 천식(asthma)과 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환, 과거 호흡기 감염(홍역, 폐렴, 결핵 등) [23] 등이 있다(Table 2). 영국흉부학회 진료지침에서는 폐 외 질환을 가진 환자들이 객담을 동반한 기침이나 반복적인 흉부 감염이 발생하는 경우에 기관지확장증을 의심해야 한다고 언급하고 있다[10]. 천식과 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환과 같은 기도 질환을 가지고 있는 환자에서는 중증의 기도 질환을 가지고 있거나 질환이 잘 조절되지 않고 악화가 잦은 경우에 기관지확장증을 의심할 것을 권유하고 있다[10]. 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환의 경우에는 안정적인 상태에서 병원균, 특히 녹농균(P. aeruginosa)이 배양된 경우도 기관지확장증을 의심해야 한다[10].

기관지확장증 진단을 위한 최적의 진단 패널이 존재하지는 않지만, 기관지확장증의 진단을 위한 진단 패널을 사용할 것을 권고하고 있다. 최근에 출간된 진료지침이나 리뷰에 따라 권고되는 검사 항목은 표 3과 같다. 미국흉부학회에서 2013년에 발간한 축약 종설(concise review) [24]에서 가장 광범위한 검사를 권고한 반면, 2017년에 발간된 유럽호흡기학회 진료지침[1]에서는 최소 번들(minimal bundle)을 권고하였다. 영국흉부학회 지침[10]에서는 자세한 과거력과 동반 질환 확인, 세균 및 항산균 동정, 면역글로불린(immunoglobulin G, A, E), 알레르기성 기관지·폐 아스퍼질러스증(allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, ABPA)에 대한 검사, 폐렴구균 백신에 대한 항체 검사는 꼭 시행할 것을 권고하였고, 자가 항체, 낭포성 섬유증 막횡단 조절 유전자(cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, CFTR), 알파-1 항트립신(alpha-1 antitrypsin) 농도 및 표현형 검사, 일차성 섬모 운동 이상증(primary ciliary dyskinesia) 검사 등은 각 질환의 임상 특징이 있는 경우에 시행할 것을 권고하였다(Table 3).

이러한 권고는 영국의 기관지확장증의 역학 연구 결과에 바탕을 둔 것으로 이를 다른 나라, 특히 결핵과 감염 후 기관지확장증이 더 많은 것으로 생각되는 아시아 국가의 임상 진료에 그대로 반영하기는 어려울 것으로 생각된다. 이러한 제한점을 극복하기 위해 국내 기도 질환 전문가들이 모여 기관지확장증 진단을 위한 공통 권고안을 제시하기도 하였는데,이 제시 안에서는 모든 환자에서 시행할 것을 권고하는 최소 진단 번들과 환자의 임상적 특징에 따른 개별화된 접근법을 강조하였다. 국내 전문가 권고안의 최소 진단 번들은 흉부 전산화 단층촬영, 일반 혈액 검사(complete blood cell count), 적혈구 침강 속도(erythrocyte sedimentation rate), C-반응 단백(C-reactive protein), 세균 및 항산균 객담 배양 검사, 폐기능 검사를 포함한다. 개별화된 진단법은 임상적으로 기관지확장증의 원인이 될 수 있는 특정 질환이 의심이 되는 경우에 검사를 시행할 것을 권고하고 있다(예, 천식이 있는 경우 알레르기성 기관지·폐 아스퍼질러스증 진단을 위해 검사를 시행, 류마티스 관절염이 의심되는 경우 자가 항체 검사 시행, 젊은 연령에서 광범위한 기관지확장증이 관찰되는 경우에 낭포성 섬유증, 일차성 섬모운동 이상증, 면역 결핍증 등 검사) (Table 4). 하지만 이 공통 권고안은 국내 기관지확장증의 역학 연구 결과가 거의 없는 상태에서 전문가들의 의견을 종합한 결과이기 때문에 향후 국내 기관지확장증 연구 결과에 바탕을 둔 진단 패널 제정이 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

천식과 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환에서 질환 중증도를 평가하는 지표들이 있듯이, 기관지확장증의 중증도를 평가하는 대표적인 지표로 기관지확장증 중증도 지표(bronchiectasis severity index, BSI) (Table 5) [25]와 FACED 지표 (Table 6) [26]가 있다. BSI와 FACED 지표 모두 기관지확장증의 예후를 잘 예측하는 것으로 보고되고 있지만 몇 가지 차이점이 있다. FACED 지표는 BSI보다 평가해야 하는 항목이 적고 장기간(> 15년) 사망 위험을 예측하는 근거가 있다는 장점이 있는 반면, BSI는 FACED 지표보다 기관지확장증의 급성 악화, 입원, 사망 위험을 더 잘 예측하는 것으로 알려져 있다[27,28]. FACED 지표가 급성 악화 예측력이 떨어지는 것을 보완하기 위해 최근 E-FACED 지표가 고안되었다[29].

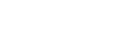

안정 시 기관지확장증 치료의 주된 목표는 1) 호흡기 증상의 완화, 2) 급성 악화의 예방, 3) 삶의 질의 향상, 4) 병의 진행 억제 등이다. 이러한 치료 목표를 위해 영국흉부학회 진료지침에서는 악화 횟수에 근거한 단계적 치료를 권고하고 있다(Fig. 1).

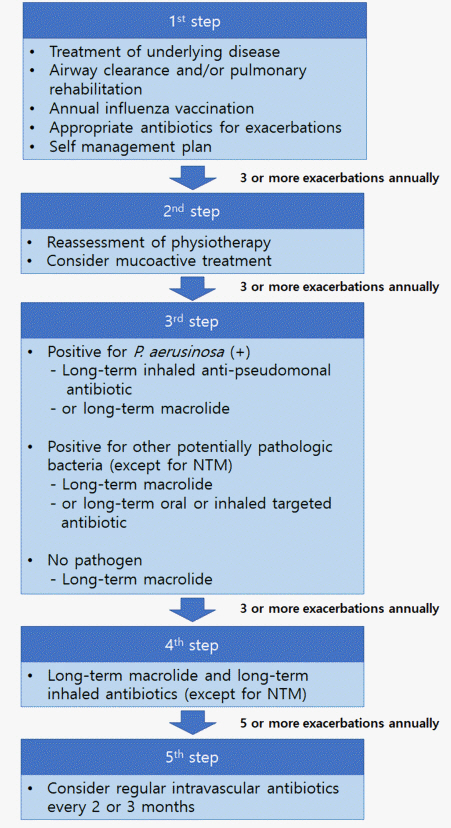

객담 배출 방법을 잘 교육하여 기도에 객담이 고여 있지 않고 청결하게 유지하는 기도 청결법은 기관지확장증의 핵심 치료법이다. 기도 청결법의 목적은 객담의 유동성을 증가시키고 효과적으로 객담을 배출하게 하여 기도 청결을 유지하는 것이다[30]. 기관지확장증이 처음 진단된 환자는 호흡 물리치료사에게 상태를 평가받고 기도 청결법에 대해 적절한 교육을 받아야 한다. 다양한 기도 청결법이 있기 때문에 환자가 어떤 청결법을 선호하는지를 고려하여 기도 청결법을 권고해야 하지만 일반적으로 단계적 물리요법(physiotherapy)이 권고되며(Fig. 2), 가능한 모든 기도 청결법에 강제 호기법(forced expiration technique, huff)을 포함하는 것을 고려해야 한다.

능동적 호흡주기 배액요법(active cycle of breathing technique)은 기관지확장증의 기도 청결을 위해 가장 흔히 사용되는 기도 청결법이다(Fig. 2) [31]. 이와 더불어 전산화단층촬영 결과를 검토하여 기관지확장증이 존재하는 기관지 폐엽을 고려한 체위배액요법(postural drainage)을 시행해야 한다. 금기증이 없다면 중력의 도움을 받는 자세를 취해 기도 청결법의 효과를 강화하는 것이 좋다. 이런 기도 청결법이 효과적이지 않은 환자는 자발배액요법(autogenic drainage) [32], 호기성 양압 기구(positive expiratory pressure) (예, 에어로비카[Aerobika], 에어로제시카[aero JESSICA], 아카펠라[Acapella], 기타) [33], 고진동 흉벽 진동(high frequency chest wall oscillation) [34]과 폐내 타진 환기(intrapulmonary percussion ventilation) [35] 등을 사용해 볼 수 있다. 기도 청결법은 적어도 10분에서 최대 30분까지 수행해야 하며, 환자가 두 번 연속 객담이 없는 헉헉거림(huff) 또는 기침을 하거나 환자가 피로해질 때까지 계속하는 것이 좋다.

국내에는 기도 청결법에 대한 교육자료가 아직 부족한 편이다. 호주와 뉴질랜드 흉부학회(Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand)에서 운영하는 Bronchiectasis Toolbox 사이트(https://bronchiectasis.au/phsiotherapy/techniques)에 방문하면 다양한 기도 청결법에 대한 영상 자료를 볼 수 있다.

유산소운동을 포함한 호흡재활치료로 환자의 운동능력을 개선할 수 있고 삶의 질 개선에도 도움이 될 수 있다. 특히 운동 불내성(exercise intolerance) 및 호흡근이 약해진 환자는 가능한 호흡 재활 프로그램에 참여하여 재활치료를 받는 것이 좋다. 재활 프로그램을 시행할 때에는 환자의 증상, 운동 능력뿐 아니라 환자의 질병 상태를 고려해야 한다.

영국흉부학회 진료지침에서는 modified Medical Research Counsil 1점 이상의 모든 환자들을 재활에 참여시킬 것을 권고하고 있다[10]. 기관지확장증 환자의 재활에는 일반적인 호흡 재활에 호흡기 근육 강화 운동(inspiratory muscle training)을 포함하는 것이 좋다.

객담 배출에 어려움을 겪고 있는 환자에게는 점액작용제 치료를 고려할 수 있다. 기도 청결을 돕기 위해 멸균 증류수 또는 생리식염수 등을 이용하여 가습(humidification)을 시도해 볼 수 있다(Fig. 2) [36,37]. 흡입 점액작용제 치료 후에는 기도 청결법을 시행해야 한다. 흡입 점액작용제, 특히 고장성 용액(예, 만니톨[mannitol], 고장성 생리식염수) 사용 시에는 기도의 과민성이 나타날 수 있기 때문에 첫 사용 시에는 기도 과민성 유발 검사(airway reactivity challenge test)를 시행해 보는 것이 좋다. 특히 천식이나 기관지 과민성이 있거나 1초간 노력성 호기량(forced expiratory volume in one second) 1 L 미만의 중증의 기도 폐쇄가 있는 경우에는 흡입 점 액작용제 사용 전에 기관지확장제를 사용하는 것을 고려해야 한다.

영국에서는 카르보시스테인(carbocysteine)이 가장 흔하게 사용하는 거담제이기 때문에 영국흉부학회 진료지침에는 카르보시스테인을 처방하였을 경우에는 최소 6개월 정도 사용하고 경과를 볼 것을 권고하고 있다[10]. 하지만 기관지확장증의 치료에 카르보시스테인의 효과를 입증한 연구는 없다. 국내에서는 에르도스테인(erdosteine)이 가장 흔히 사용되는 약제이지만 에르도스테인이 기관지확장증 치료에 도움이 된다는 임상적 증거는 미약하다. 최근 중국에서 시행한 한 연구에서 아세틸시스테인(N-acetylcysteine)이 기관지확장증의 악화를 감소시켰다고 보고하였지만[38], 연구의 1차 목표의 정의 등에 문제가 있어 결과를 그대로 신뢰하기는 어렵다. 하지만 많은 의사들이 경구 거담제가 효과는 약하지만 기관지확장증의 치료에 도움이 될 수 있다고 생각하고 있다.

기관지확장증에서 흡입 스테로이드의 치료 효과를 분석하기 위해 7개의 무작위 배정 연구를 메타 분석한 한 연구에 의하면, 6개월 이내로 흡입 스테로이드의 사용은 폐기능과 악화에 유의한 영향을 미치지 못하였다[39]. 6개월 이상 흡입 스테로이드의 사용 역시 폐기능, 삶의 질, 악화에 유의한 변화를 일으키지 못하였다. 한 연구에서 흡입 스테로이드의 사용이 객담 양과 호흡곤란을 감소시킬 수 있다고 보고를 하기도 하였지만[40], 흡입 스테로이드의 사용에 의한 국소 또는 전신 부작용의 발생을 조심해야 한다. 경구 스테로이드의 기관지확장증의 안정 시와 악화 시 효과에 대해 연구한 무작위 배정 연구는 없다. 또한 phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor (PDE4 억제제)나 methylxanthine이 기관지확장증에 효과적인지 연구한 임상 연구 또한 존재하지 않는다. 이러한 연구 결과를 바탕으로 천식, 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환, 염증성 장질환, 알레르기성 기관지·폐 아스퍼질러스증 등의 질환이 없는 경우에는 흡입 스테로이드나 경구 스테로이드를 사용하지 않을 것을 권고하고 있다. PDE4 억제제나 methylxanthine 또한 권고되지 않는다.

영국흉부학회 진료지침은 1년에 3번 이상 악화를 경험하는 환자에게는 장기간 흡입 항생제를 사용하는 것을 권고하고 있으나(Fig. 1) [10], 국내에서는 거의 사용되고 있지 않다. 장기 항생제 흡입치료 효과로 기도에 세균을 제거하여 악화를 줄일 수 있으나 그 효과가 마크로라이드(macrolide) 장기 치료보다는 약하며 비용이 매우 비싸며 국내 의료보험 적응증을 받지 못하였다.

영국흉부학회 진료지침에서는 녹농균이 배양된 경우에는 흡입 항녹농균 항생제를, 녹농균이 배양되지 않는 경우에는 마크로라이드 장기요법을 먼저 고려할 것을 권고하고 있다[10]. 하지만 최근 메타 분석에 의하면 마크로라이드는 전체 기관지확장증 환자에서 악화의 빈도를 약 50% 감소(adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.49)시켰는데, 이 효과는 특히 객담에서 녹농균이 배양이 된 환자에서 효과가 더 좋았다(adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.36) [41]. 흡입 항생제가 악화의 빈도를 약 20% (rate ratio, 0.81)를 감소시키고 그 효과가 객담에서 녹농균의 배양 여부에 따라 차이가 없다는 점을 고려한다면[42], 이러한 권고 사항은 향후 수정될 것으로 예상된다.

1년 또는 그 이상 마크로라이드(아지스로마이신, 에리스로마이신 등)를 투여하면 기관지확장증의 악화를 예방할 수 있다는 사실은 무작위 임상시험을 통해서 그 효과가 잘 입증되었다[41]. 하지만 부작용으로 내성균 출현, 청력 감소, 심전도 변화(예, QT prolongation) 등이 생길 수 있어서 모든 기관지확장증 환자를 마크로라이드로 장기간 치료할 것은 아니고 연간 3회 이상 잦은 악화를 경험한 환자나 입원이 필요하였던 중증 악화를 경험한 환자가 마크로라이드 장기간 치료의 대상이 된다. 하지만 마크로라이드 단독 치료가 마크로라이드 내성 비결핵항산균 폐질환(non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease)의 위험인자임을 고려할 때[43], 기관지확장증 환자에게 마크로라이드를 장기간 투여하는 치료는 신중하게 고려해야 할 것으로 생각된다. 향후 기관지확 장증 환자의 마크로라이드 장기간 치료에 대한 국내 지침이 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

기관지확장증 환자의 상당수가 기류 제한(airflow limitation)이 있고, 약 60%의 환자가 호흡곤란을 호소하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 호흡곤란과 폐기능 저하가 있는 경우, 흡입 기관지확장제(inhaled bronchodilator)를 사용할 수 있다. 이런 경우는 경구보다는 흡입 지속성 무스카린 길항제(long-acting muscarinic antagonist) 및 지속성 베타2 항진제(long-acting beta-2 agonist)를 사용한다. 국내에서 시행된 한 후향적 연구는 기류 제한을 동반한 기관지확장증 환자에게 3-6개월 동안 흡입 기관지 확장제 치료를 한 결과, 의미 있는 폐기능의 개선이 있었다고 보고하기도 하였다[44]. 하지만 기관지확장증에서 흡입 항생제의 효과를 입증한 무작위 임상 시험이 없기 때문에 이에 대해서는 향후 연구가 필요하다.

국내 기관지확장증의 유병률은 유럽이나 미국 등 서양 국가들에 비해 높은 편이다. 하지만 국내 연구의 부족으로 인하여 기관지확장증의 주요 원인 등에 대해서는 아직 알려져 있지 않다. 다행히도 국내 다기관 기관지확장증 연구회(Korean Multicenter Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration, KMBARC)가 결성되어 2017년부터 활발히 활동을 하고 있으며, 대한결핵및호흡기학회 산하 기관지확장증 연구회가 2020년부터 활동을 시작하였으므로 조만간 국내 기관지확장증 환자를 대상으로 많은 연구 결과가 나올 것으로 생각된다[46,47]. 이러한 연구 결과를 토대로 국내 실정에 맞는 기관지확장증 진료지침이 제정되면 국내 기관지확장증 환자의 진단에 큰 도움을 줄 것이다.

본고에서는 최근 개정된 영국흉부학회의 성인 기관지확장증 진료지침을 중심으로 기관지확장증의 임상 접근법 및 치료에 대해서 살펴보았다. 기관지확장증은 만성적인 객담을 호소하는 환자에서 의심을 해야 하는 질환으로 특히 기관지확장증의 위험이 있는 환자에서는 반드시 조사가 필요하다. 천식, 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환과 같은 기도 질환의 중증도가 높거나 악화가 잦은 경우에는 기관지확장증이 동반되었는지 확인해야 하며, 결체조직 질환, 염증성 장질환, 면역결핍 등과 같은 질환을 가진 환자가 만성적인 객담을 호소한다면 기관지확장증에 대한 검사가 필요하다. 기관지확장증 진단을 위한 최선의 진단 패널은 존재하지 않기 때문에 국내 연구를 바탕으로 한 진단 패널 개발이 필요할 것으로 생각된다. 기관지확장증 치료의 핵심은 기도 청결이며 객담이 고이지 않게 배출하는 방법을 환자가 잘 숙지하는 것이 필요하며 점액작용제가 도움이 될 수 있다. 또한 악화 및 폐렴을 예방하기 위해서 폐렴 구균 백신과 독감 백신을 꼭 처방해야 하며, 환자 중 악화가 잦거나 악화가 심한 경우에는 마크로라이드 장기간 치료를 고려해 볼 수 있겠지만, 비결핵항산균 폐질환이 동반되었거나 의심이 되는 경우 마크로라이드 단독 치료는 내성균을 유발할 수 있기 때문에 주의를 기울여야 한다.

REFERENCES

1. Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1700629.

2. Chandrasekaran R, Mac Aogáin M, Chalmers JD, Elborn SJ, Chotirmall SH. Geographic variation in the aetiology, epidemiology and microbiology of bronchiectasis. BMC Pulm Med 2018;18:83.

3. Weycker D, Hansen GL, Seifer FD. Prevalence and incidence of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis among US adults in 2013. Chron Respir Dis 2017;14:377–384.

4. Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Diel R, Hohmann D, Welte T, Rademacher J. Bronchiectasis in Germany: a population-based estimation of disease prevalence. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1805–1807.

5. Sánchez-Muñoz G, López de Andrés A, Jiménez-García R, et al. Time trends in hospital admissions for bronchiectasis: analysis of the Spanish national hospital discharge data (2004 to 2013). PLoS One 2016;11:e0162282.

6. Quint JK, Millett ER, Joshi M, et al. Changes in the incidence, prevalence and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016;47:186–193.

7. Choi H, Yang B, Nam H, et al. Population-based prevalence of bronchiectasis and associated comorbidities in South Korea. Eur Respir J 2019;54:1900194.

8. Goeminne PC, De Soyza A. Bronchiectasis: how to be an orphan with many parents? Eur Respir J 2016;47:10.

10. Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax 2019;74(Suppl 1):1–69.

11. Lucidarme O, Grenier P, Coche E, Lenoir S, Aubert B, Beigelman C. Bronchiectasis: comparative assessment with thin-section CT and helical CT. Radiology 1996;200:673–679.

12. van der Bruggen-Bogaarts BA, van der Bruggen HM, van Waes PF, Lammers JW. Assessment of bronchiectasis: comparison of HRCT and spiral volumetric CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1996;20:15–19.

13. Brody A, Chang A. The imaging definition of bronchiectasis in children: is it time for a change? Pediatr Pulmonol 2018;53:6–7.

14. Kim SJ, Im JG, Kim IO, et al. Normal bronchial and pulmonary arterial diameters measured by thin section CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995;19:365–369.

15. Chalmers JD, Chang AB, Chotirmall SH, Dhar R, McShane PJ. Bronchiectasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4:45.

16. Shoemark A, Ozerovitch L, Wilson R. Aetiology in adult patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med 2007;101:1163–1170.

17. Skare TL, Nakano I, Escuissiato DL, Batistetti R, Rodrigues Tde O, Silva MB. Pulmonary changes on high-resolution computed tomography of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their association with clinical, demographic, serological and therapeutic variables. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51:325–330.

18. Tsuchiya Y, Takayanagi N, Sugiura H, et al. Lung diseases directly associated with rheumatoid arthritis and their relationship to outcome. Eur Respir J 2011;37:1411–1417.

19. Black H, Mendoza M, Murin S. Thoracic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Chest 2007;131:524–532.

20. Clausen E, Wittman C, Gingo M, et al. Chest computed tomography findings in HIV-infected individuals in the era of antiretroviral therapy. PloS one 2014;9:e112237.

21. Honarbakhsh S, Taylor GP. High prevalence of bronchiectasis is linked to HTLV-1-associated inflammatory disease. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:258.

22. José RJ, Hall J, Brown JS. De novo bronchiectasis in haematological malignancies: patient characteristics, risk factors and survival. ERJ Open Res 2019;5:00166–02019.

23. Dhar R, Singh S, Talwar D, et al. Bronchiectasis in India: results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and respiratory research network of India registry. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e1269–e1279.

24. McShane PJ, Naureckas ET, Tino G, Strek ME. Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:647–656.

25. Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:576–585.

26. Martínez-García MÁ, de Gracia J, Vendrell Relat M, et al. Multidimensional approach to non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the FACED score. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1357–1367.

27. Ellis HC, Cowman S, Fernandes M, Wilson R, Loebinger MR. Predicting mortality in bronchiectasis using bronchiectasis severity index and FACED scores: a 19-year cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016;47:482–489.

28. Guan WJ, Chen RC, Zhong NS. The bronchiectasis severity index and FACED score for bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2016;47:382–384.

29. Martinez-Garcia MA, Athanazio RA, Girón R, et al. Predicting high risk of exacerbations in bronchiectasis: the E-FACED score. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:275–284.

30. Murray MP, Pentland JL, Hill AT. A randomised crossover trial of chest physiotherapy in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2009;34:1086–1092.

31. O'Neill B, Bradley JM, McArdle N, MacMahon J. The current physiotherapy management of patients with bronchiectasis: a UK survey. Int J Clin Pract 2002;56:34–35.

32. Herrero-Cortina B, Vilaró J, Martí D, et al. Short-term effects of three slow expiratory airway clearance techniques in patients with bronchiectasis: a randomised crossover trial. Physiotherapy 2016;102:357–364.

33. Eaton T, Young P, Zeng I, Kolbe J. A randomized evaluation of the acute efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of flutter and active cycle of breathing with and without postural drainage in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Chron Respir Dis 2007;4:23–30.

34. Nicolini A, Cardini F, Landucci N, Lanata S, Ferrari-Bravo M, Barlascini C. Effectiveness of treatment with high-frequency chest wall oscillation in patients with bronchiectasis. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:21.

35. Paneroni M, Clini E, Simonelli C, Bianchi L, Degli Antoni F, Vitacca M. Safety and efficacy of short-term intrapulmonary percussive ventilation in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Care 2011;56:984–988.

36. Nicolson CH, Stirling RG, Borg BM, Button BM, Wilson JW, Holland AE. The long term effect of inhaled hypertonic saline 6% in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respir Med 2012;106:661–667.

37. Bilton D, Tino G, Barker AF, et al. Inhaled mannitol for non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a randomised, controlled trial. Thorax 2014;69:1073–1079.

38. Qi Q, Ailiyaer Y, Liu R, et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on exacerbations of bronchiectasis (BENE): a randomized controlled trial. Respir Res 2019;20:73.

39. Kapur N, Petsky HL, Bell S, Kolbe J, Chang AB. Inhaled corticosteroids for bronchiectasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;5:CD000996.

40. Elborn JS, Johnston B, Allen F, Clarke J, McGarry J, Varghese G. Inhaled steroids in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med 1992;86:121–124.

41. Chalmers JD, Boersma W, Lonergan M, et al. Long-term macrolide antibiotics for the treatment of bronchiectasis in adults: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:845–854.

42. Laska IF, Crichton ML, Shoemark A, Chalmers JD. The efficacy and safety of inhaled antibiotics for the treatment of bronchiectasis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:855–869.

43. Griffith DE, Brown-Elliott BA, Langsjoen B, et al. Clinical and molecular analysis of macrolide resistance in Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:928–934.

44. Jeong HJ, Lee H, Carriere KC, et al. Effects of long-term bronchodilators in bronchiectasis patients with airflow limitation based on bronchodilator response at baseline. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:2757–2764.

45. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Adult immunization schedule recommended 2019 [Internet]. Seoul (KR): Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, c2019 [cited 2020 May 15]. Available from: http://www.ksid.or.kr/file/2019_vaccine.pdf

Table 1.

CT imaging parameters for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis

| Imaging parameters | |

|---|---|

| Slice thickness | ≤ 1 mm |

| Reconstruction algorithm | High spatial frequency |

| kVp | 100–140 |

| mAs (or effective mAs) | 100–200 |

| Gantry rotation time | < 0.5 second |

Table 2.

Investigation for causes of bronchiectasis according to comorbidities

Table 3.

Comparison of the diagnostic panels for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis

| British Thoracic Society guideline (2019) | European Respiratory Society guideline (2017) | American Thoracic Society (2013)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive assessment of history and comorbidities | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Bacterial and mycobacterial culture | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| IgG, A, and E | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Test for ABPA (including IgE) | ○ | ○ | |

| Antibody titers to pneumococcal vaccine | ○ | ○ | |

| Auto-antibodies (e.g., ANA, RF, anti-CCP, SSA, SSB Ab, ANCA) | Patients with suspected connective tissue disease | ○ | |

| CFTR genetic mutation analysis | Patients with suspected cystic fibrosis | ○ | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin level and phenotype | Patients with suspected Alpha-1 anti-trypsinase deficiency | ○ | |

| Test for primary ciliary dyskinesia | Patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia | Patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia |

Table 4.

A consensus diagnostic testing panel for bronchiectasis by Korean experts

Table 5.

Bronchiectasis severity index

Table 6.

FACED/E-FACED score

| Points | FEV1, %predicted | Age (years) | P. aeruginosa colonization | Extension (radiologic severity) | Dyspnea (mMRC dyspnea scale) | At least one severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the previous yeara |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ≥ 50% | < 70 | No | 1-2 lobes | 0-2 | No |

| 1 | Yes | ≥ 3 lobes | ≥ 3 | |||

| 2 | < 50 | ≥ 70 | Yes |

The FACED index is classified into mild (0-2 points), moderate (3-4 points) and severe (5-7 points). The E-FACED score is classified into mild (0-3 points), moderate (4-6 points) and severe (7-9 points).

FACED, FEV1, age, colonization, extension, dyspnea; E-FACED, exacerbation-FACED; mMRC, modified medical research council, FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 10,802 View

- 1,035 Download

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print