|

|

| Korean J Med > Volume 94(1); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are alternatives to vitamin K antagonists to prevent stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) and have emerged as the preferred choice. The use of NOACs is rapidly increasing in Korea after coverage by insurance since 2015. However, the rate of prescribing anticoagulants in Korean patients with AF remains low compared to other countries. Most of the NOAC anticoagulant prescriptions are issued at hospitals. As the prevalence rate of AF in Korea is expected to increase rapidly with the increase in the elderly population, the need to prescribe NOACs in primary care clinics will also increase. Therefore, The Korean Heart Rhythm Society organized the Korean Atrial Fibrillation Management Guideline Committee and analyzed all available studies based on the 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of NOACs for managing AF, as well as studies on Korean patients. The authors would like to introduce practical guidelines for NOAC prescriptions in Korean patients with AF.

ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļ╣ä-ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£(non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant, NOAC)ļŖö ĒÖ£ļ░£ĒĢśĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳Ļ│Ā, ĻĘĖ ņ▓śļ░®ņØ┤ ļŹö ļŖśņ¢┤ļéĀ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņśłņāüļÉ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļ¦×ņČöņ¢┤ ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜīņŚÉņä£ļŖö NOAC ņ▓śļ░®ņØś ņŗ£ņ×æĻ│╝ ņ£Āņ¦Ćņŗ£ ņŻ╝ņØśĒĢĀ ņĀÉņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņäżļ¬ģĒĢśĻ│Āņ×É ĒĢ£ļŗż.

Ēśäņ×¼ ĻĄŁļé┤ ļ░Å ņÖĖĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś, ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś ļō▒ņØś NOACĻ░Ć ļ╣äĒīÉļ¦ēņä▒ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņŚÉņä£ ļćīņĪĖņżæ ņśłļ░®ņØä ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒŚłĻ░ĆļÉśņ¢┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. NOACļŖö ņØĖĻ│Ą ĻĖ░Ļ│ä ĒīÉļ¦ē ļśÉļŖö ņżæļō▒ļÅä ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ Ēśæņ░®ņ”ØņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļ¦ī ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ×ģņ”ØļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ NOACļŖö ĻĘĖ ņÖĖ ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒīÉļ¦ē ņ¦łĒÖśņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗż(Table 1) [1-3]. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ 2016 European Society of Cardiology ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ŌĆśļ╣äĒīÉļ¦ēņä▒ŌĆÖņØ┤ļØ╝ļŖö ņÜ®ņ¢┤Ļ░Ć ņéŁņĀ£ļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░, ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜī ņŗżņÜ® ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļÅä Ēś╝ļÅÖņØä Ēö╝ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ŌĆ£ļ╣äĒīÉļ¦ēņä▒ŌĆØņØ┤ļ×Ć ņÜ®ņ¢┤ļź╝ ņéŁņĀ£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż[1,3]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØ┤ ņÜ®ņ¢┤ļŖö ņ×äņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ņĀ£ņÖĖ ĻĖ░ņżĆņŚÉ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉ£ ņĄ£ņ┤łņØś ļŗ©ņ¢┤ņØ┤ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ Ļ░ü NOACņØś ņĀ£ĒÆł ĒŖ╣ņä▒ ņÜöņĢĮņŚÉ ĻĖ░ņłĀļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż.

ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ņŚÉļŖö ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£(vitamin K antagonist; ļīĆĒĢ£ļ»╝ĻĄŁņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ļ¦īņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£, ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢ©)ņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ĒīÉļ¦ē ņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ evaluated heat valves, rheumatic or artificial (EHRA) 1ĒśĢ, ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā NOAC ļ░Å ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ ņāüņÜ®ņØ┤ ļ¬©ļæÉ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ EHRA 2ĒśĢņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČäļźśĒĢśĻĖ░ļÅä ĒĢ£ļŗż[3]. EHRA 2ĒśĢņØĆ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ ļśÉļŖö NOACļĪ£ ĒśłņĀäņāēņĀäņ”Ø ņśłļ░®ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØ┤ļ®░, ņżæļō▒ļÅä ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ Ēśæņ░®ņØä ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ ļ¬©ļōĀ ĒīÉļ¦ē ņ¦łĒÖś, ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ ņä▒ĒśĢņłĀ, ņĪ░ņ¦ü ĒīÉļ¦ē ņ╣śĒÖś ļśÉļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒö╝ņĀü ļīĆļÅÖļ¦ź ĒīÉļ¦ē ņżæņ×¼ņłĀ(trans-catheter aortic valve implantation)ņØä ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢ£ļŗż[3]. EHRA 2ĒśĢ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņØĆ NOAC ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳Ļ│Ā, ņÖĆĒīīļ”░Ļ│╝ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢ£ ĒÜ©ļŖź ļ░Å ņĢłņĀĢņä▒ņØä ļ│┤ņśĆĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ[3-9], ņØ┤ļōż ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö NOACĻ░Ć ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż(Table 1) [1,3,10]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņĪ░ņ¦üĒīÉļ¦ē ņ╣śĒÖśņłĀ ļśÉļŖö ĒīÉļ¦ē ņä▒ĒśĢņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēļ░øņØĆ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņ╣śļŻīņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ļģ╝ļ×ĆņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż[3,6,7,11]. ĒīÉļ¦ē ņ╣śĒÖśņłĀ ņ×Éņ▓┤ļĪ£ ņןĻĖ░Ļ░äņØś Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ ņ╣śļŻīĻ░Ć ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļÅÖļ░śļÉ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņØś ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ NOACņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ĒāĆļŗ╣ĒĢ£ ņ╣śļŻī ņśĄņģśņØ┤ļŗż. ļźśļ¦łĒŗ░ņŖżņä▒ ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ Ēśæņ░®ņ”ØņŚÉ ņĪ░ņ¦üĒīÉļ¦ē ņ╣śĒÖśņłĀņØä ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ņśłņÖĖņŚÉ ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņŚÉņä£ ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ ņ╣śĒÖśņłĀ Ēøä ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ ĒśłļźśļŖö ņĀĢņāüĒÖöļÉśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņŗ¼ļ░®ņØĆ ņŚ¼ņĀäĒ׳ ĒÖĢņןļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳Ļ│Ā ļ╣äņĀĢņāüņĀüņØ┤ļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØ┤ ņäĀĒśĖļÉśļŖö ņśĄņģśņØ┤ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņČöĻ░Ć ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż.

Ļ▓ĮĒö╝ņĀü ļīĆļÅÖļ¦ź ĒīÉļ¦ē ņŗ£ņłĀ ņØ┤Ēøä NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀäĒ¢źņĀüņØĖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ņŚåĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ļōż ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ ļŗ©ļÅģ ļśÉļŖö ļ│ĄĒĢ® ņÜöļ▓ĢņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[2]. Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØś ņČöĻ░ĆļŖö ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņØä ņāüņŖ╣ņŗ£ĒéżĻ│Ā ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņĪ░ĒĢ® ļ░Å ĻĖ░Ļ░äņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņ¦äĒ¢ē ņżæņØĖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĻĖ░ļŗżļĀż ļ│┤ņĢäņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ļ╣äĒøäņä▒ ņŗ¼ĻĘ╝ņ”Ø ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņØĆ ĒśłņĀäņāēņĀäņ”ØņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉņØ┤ļŗż[12,13]. ĻĖ░Ļ│ä ĒīÉļ¦ē ļśÉļŖö ļźśļ¦łĒŗ░ņŖżņä▒ ņŖ╣ļ¬©ĒīÉ Ēśæņ░®ņ”ØĻ│╝ ļŗ¼ļ”¼ NOACĻ░Ć ņÖĆĒīīļ”░Ļ│╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŚ┤ļō▒ĒĢśļŗżĻ│Ā ņČöļĪĀĒĢĀ ļ¦īĒĢ£ ĒĢ®ļ”¼ņĀüņØĆ ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░Ļ░Ć ņŚåļŗż. ļ░śļīĆļĪ£ ļ╣äĒøäņä▒ ņŗ¼ĻĘ╝ļ│æņ”ØņŚÉ ļÅÖļ░śļÉ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņØĆ ņóīņŗ¼ņŗż ĻĄ¼ĒśłļźĀņØ┤ ņ£Āņ¦ĆļÉ£ ņŗ¼ļČĆņĀä ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ņØś ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖĻ│╝ ļ¦ÄņØĆ ņ£Āņé¼ņä▒ņØ┤ ņ׳Ļ│Ā, ļåÆņØĆ CHA2DS2-VASC ņĀÉņłś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ NOACņØś ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ”Øļ¬ģļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£, NOAC ņ╣śļŻīļŖö ņĀüņĀłĒĢśļŗżĻ│Ā ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[14-16].

ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ņ╣śļŻī ņĀüņØæņØ┤ ļÉśļŖö ĒÖśņ×É ņäĀņĀĢ ļ░Å ņÖĆĒīīļ”░Ļ│╝ NOACņØś ņäĀĒāØņØĆ ņŻ╝ņØśĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļ®░ ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØ┤ ļÅäņøĆņØ┤ ļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ļ¬©ļōĀ NOACļŖö ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśĻ│Ā ņŗ¼ĒĢ£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĻĖłņ¦ĆļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ│┤Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ Ļ░ü ņĢĮņĀ£ļ¦łļŗż ļ│┤ņ£ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö Ļ│Āņ£ĀņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒, ĒÖśņ×É Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ņ×äņāü ņÜöņØĖ, ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņäĀĒśĖļÅä ļ¬©ļæÉĻ░Ć Ļ│ĀļĀżļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[17-19].

ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜī ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ Ļ░ĆņØ┤ļō£ļØ╝ņØĖņØĆ ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ļćīņĪĖņżæ ņśłļ░®ņØä ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, NOACņØś ņóģĒĢ®ņĀüņØĖ ņ×äņāüņĀü ņØ┤ļōØņŚÉ ļ░öĒāĢĒĢśņŚ¼, NOACņØś ĒŖ╣ļ│äĒĢ£ ĻĖłĻĖ░ņ”ØņØ┤ ņŚåļŖö ĒĢ£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ļ│┤ļŗż NOACļź╝ ņäĀĒśĖĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż(class I, level of evidence A) [20].

ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć, ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś ļō▒ ņĀä ņäĖĻ│äņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£ĒīÉļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö ļäż Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ļ¬©ļōĀ NOACĻ░Ć ņ▓śļ░® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśĻ│Ā, Ļ░üĻ░üņØś ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░Éļ¤ē ĻĖ░ņżĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ▓śļ░® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗż. ĻĄŁļé┤ ļ│┤ĒŚś ĻĖ░ņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö CHA2DS2-VASc ņĀÉņłśĻ░Ć 2ņĀÉ ņØ┤ņāüņØĖ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ĻĖēņŚ¼ ņØĖņĀĢņØ┤ ļÉ£ļŗż. ļäż Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć NOAC ļ¬©ļæÉ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņ×äņāü ņŗ£ĒŚśņŚÉņä£ ĒÜ©ļŖźĻ│╝ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ņØ┤ ņ×ģņ”ØļÉśņŚłļŗż. Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś)Ļ│╝ ROCKET-AF (ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś) ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĻĖ░ļ│ĖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØ┤ ņŻ╝ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļÉśĻ│Ā ĒÖśņ×É ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ņäżĻ│äļÉśņŚłļŗż[21,22]. ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļ░śĒĢśņŚ¼ randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY, ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć)ņÖĆ Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation (ENGAGE-AF, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś) ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö Ļ│ĀņÜ®ļ¤ē, ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ĻĄ░ņŚÉ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×É ņłśļź╝ ļ░░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ņäżĻ│äļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö Ļ│ĀņÜ®ļ¤ē, ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ĻĄ░ ļé┤ņŚÉņä£ ĒŖ╣ņĀĢ ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ņäżĻ│äļÉśņŚłļŗż[23,24]. Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ Ēæ£ņżĆ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś NOACļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņØĆ ŌĆś2018 ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜī ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØś ņĀüĒĢ®ĒĢ£ ņäĀĒāØ ļ░Å ņÜ®ļ¤ē ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłŌĆÖņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ£ļŗż[25]. ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö ņĢĮņĀ£ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĆĒåĀĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļ®░ ņĢĮņĀ£ Ļ░ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ļÅä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ļéśņØ┤, ņ▓┤ņżæ, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź, ļŗżļźĖ ļÅÖļ░ś ņ¦łĒÖśļÅä Ļ│ĀļĀżļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ│╝Ļ▒░ ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņČ£ĒśłņØ┤ļéś ĻČżņ¢æņØ┤ ņ׳ņŚłļŹś ĒÖśņ×Éļéś ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ļ│ĄņĢĮņØ┤ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ņ£äņןĻ┤Ć ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśļÅä Ļ░Éņåīļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒöäļĪ£Ēåż ĒÄīĒöä ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£(proton pump inhibitor, PPI) ļ│ĄņÜ®ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ£ļŗż[26,27]. PPIņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØ┤ļéś ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉ ņĢĮņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉņä£ ņ£äņן ļ│┤ĒśĖ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ”Øļ¬ģļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļéś, NOACņŚÉņä£ņØś ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ļŖö ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀüņØ┤ļŗż[28-31]. ĒÖśņ×Éļ│ä ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ NOAC ņóģļźś ņäĀĒāØņŚÉ ļÅäņøĆņØä ņŻ╝ļŖö ņ¦äļŻī ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØä ņ░ĖĻ│ĀĒĢśĻĖ░ ļ░öļ×Ćļŗż[32-35].

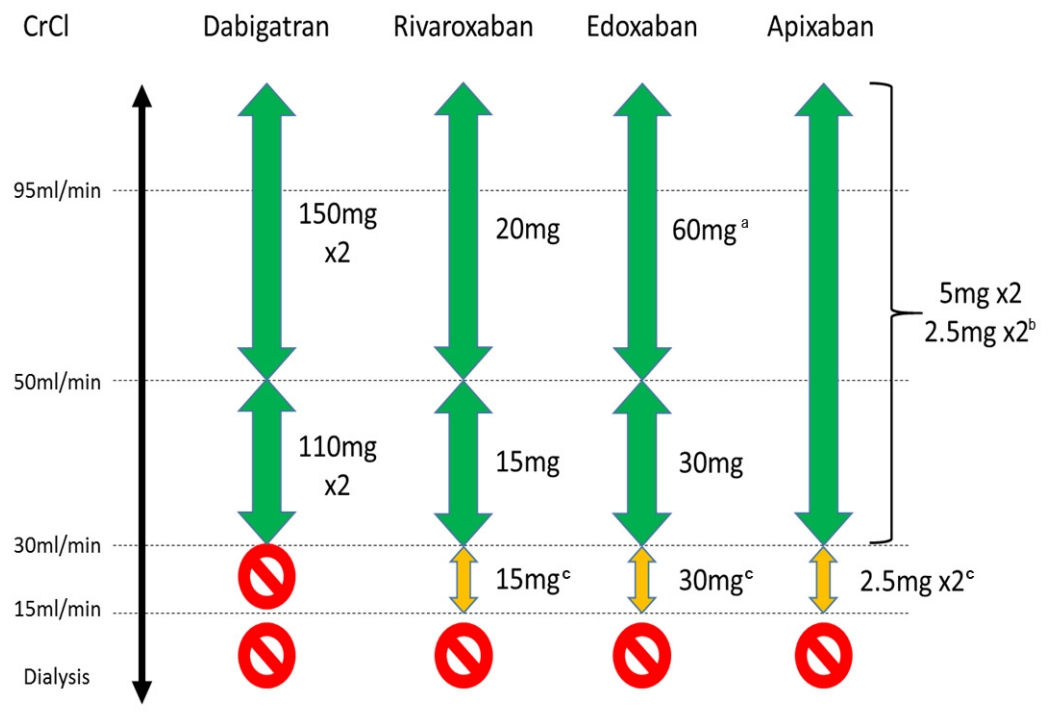

ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØä ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżĻ│╝ ļ¦łņ░¼Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļĪ£ NOACļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżļÅä ņ╣śļŻīņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņāüņäĖĒĢ£ ĻĄÉņ£ĪņØĆ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜīņŚÉņä£ ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśļŖö ĒåĄņØ╝ļÉ£ NOAC ĒÖśņ×É Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ ņ╣┤ļō£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØä ņČöņ▓£ĒĢ£ļŗż(Figs. 1 and 2).

ļ¦ż ņ¦äļŻīļ¦łļŗż ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ļ│ĄņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØä ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖņØ┤ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ņĢĮņØä Ļ╣£ļ░ĢĒĢśĻ│Ā ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢī ņ¢┤ļ¢╗Ļ▓ī ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļŖöņ¦Ć ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ņŚ¼Ē¢ēņŗ£ņŚÉ ņĢĮņØä ĒĢŁņāü ņ¦Ćņ░ĖĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä Ļ░ĢņĪ░ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. NOAC ĒÖśņ×É Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ ņ╣┤ļō£ņŚÉ ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņŻ╝ņÜö ņé¼ĒĢŁļōżņØ┤ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ņ×ÉņäĖĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×É ĻĄÉņ£ĪņØä ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļŗżņØīņØś ņ░ĖĻ│Āļ¼ĖĒŚīņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳Ļ▓Āļŗż[17,19,36,37].

ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ļ░øļŖö ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņäĖņŗ¼ĒĢ£ ņĀĢĻĖ░ņĀü ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņČ£ĒśłņØ┤ ņĪ░ņןļÉĀ ņłśļÅä Ēś╣ņØĆ ļćīņĪĖņżæņØä ņśłļ░®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć Ļ░ÉņåīļÉĀ ņłśļÅä ņ׳ļŗż. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć Ļ│ĀļĀ╣ņØ┤Ļ▒░ļéś ĒŚłņĢĮĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ░£ņāØ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”ØņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒĢŁņāü ņŻ╝ņØśĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢ£ ņØ┤Ēøä ĒĢ£ ļŗ¼ ļÆż ņĀĢĻĖ░ ļ░®ļ¼ĖņØä ņČöņ▓£ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņØ┤ĒøäļČĆĒä░ļŖö ņĀüņ¢┤ļÅä 3Ļ░£ņøöņŚÉ ĒĢ£ ļ▓ł ņĀĢĻĖ░ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ¦äļŻīĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ņČöņ▓£ĒĢ£ļŗż. NOAC ņ▓śļ░® Ļ▓ĮĒŚśņØ┤ ņīōņØ┤ļ®┤ ĒÖśņ×É ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØ┤ļéś ņ¦äļŻī ĻĖ░Ļ┤ĆņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĀĢĻĖ░ņĀü ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä ļŹö ĻĖĖĻ▓ī ņäżņĀĢĒĢĀ ņłśļÅä ņ׳Ļ▓Āļŗż(Fig. 3) [38,39].

Ēæ£ 2ņÖĆ ĻĘĖļ”╝ 3ņŚÉ ņāüĒÖ®ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŗ£ņĀÉņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĖ░ņłĀĒĢśņśĆļŗż. Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņĀÉņØĆ ĒÖśņ×É ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ│ĀļĀżņØ┤ļŗż. ņśłļź╝ ļōżņ¢┤, Ļ│ĀļĀ╣ņØ┤Ļ▒░ļéś(75ņäĖ ņØ┤ņāü), ĒŚłņĢĮĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×É, Ļ░äĻĖ░ļŖźņØ┤ļéś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ļÅÖļ░śļÉ£ Ļ░ÉņŚ╝ņØ┤ļéś ņĢöņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØä ņóĆ ļŹö ņ×ÉņŻ╝ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[40,41]. ļśÉĒĢ£ ļćīņĪĖņżæ ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļŖö ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ņ¦Ćļé©ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļ│ĆĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĒÖśņ×É ļ░®ļ¼Ėņŗ£ ļ¦łļŗż ņ×¼ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[42]. ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļÅä ļ¦łņ░¼Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆļĪ£ ņóģĒĢ®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÅēĻ░ĆļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż[43-47]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļåÆņØĆ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ņ×Éņ▓┤Ļ░Ć ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ņ╣śļŻīņØś ĻĖłĻĖ░ņ”ØņØĆ ņĢäļŗłļŗż. ĻĘĖ ņØ┤ņ£ĀļŖö ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņŚÉ ļ╣äļĪĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļćīņĪĖņżæ ņ£äĒŚśļÅäļÅä ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż[17,48]. ņØ╝ļŗ© ĻĄÉņĀĢ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×Éļź╝ ņĄ£ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĄÉņĀĢĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņČöņ▓£ļÉ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ļģĖņćĀĒĢ©ņØ┤ļéś ļéÖņāü ņ£äĒŚśņØĆ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ņØś ĻĖłĻĖ░ņ”ØņØ┤ ņĢäļŗłļ®░, ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņĀüĒĢ®ĒĢ£ ņĄ£ņāüņØś ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ ņóģļźś ļ░Å ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņäĀĒāØĒĢśņŚ¼ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×É ĻĄÉņ£Ī ļ░Å ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ņØä ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņČöņ▓£ļÉ£ļŗż.

ņ¦¦ņØĆ ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ļź╝ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢī NOACņØś ļ│ĄņÜ® ņł£ņØæļÅäļŖö ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļŖöļŹ░ ĒĢäņłśņĀüņØ┤ļŗż[49]. ņÖ£ļāÉĒĢśļ®┤, ļ│ĄņĢĮ 12-24ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļé┤ņŚÉ ņĀÉņ░©ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż. NOAC ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅä ĒÅēĻ░Ćļź╝ ņĢĮņĀ£ Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļéś ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņØĖ ņØæĻ│Ā Ļ▓Ćņé¼ļĪ£ ņŗ£Ē¢ēĒĢ©ņØĆ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņĀüĒĢ®ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ļÅÖļ░ś ņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ ļ¦ÄĻ▒░ļéś Ļ│ĀļĀ╣ņØ┤Ļ▒░ļéś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśĻ░Ć ņ׳Ļ▒░ļéś ļģĖņćĀĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ NOACļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŹöļØ╝ļÅä ņĀĢĻĖ░ņĀü ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ņØ┤ ĒĢäņłśņĀüņØ┤ļŗż.

ņŗżņĀ£ ņ¦äļŻī ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņŚÉņä£ NOAC ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļŖö 38%ņŚÉņä£ 99%ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉ£ļŗż[50-61]. NOAC ļ│ĄņÜ®ņØś ļé«ņØĆ ņł£ņØæļÅäļŖö ņ╣śļŻīļĪ£ ņ¢╗ņØä ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņØ┤ļōØņØä ņŗ¼ĒĢśĻ▓ī Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£Ēé©ļŗż. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ŌĆśņŗżņĀ£ ņ¦äļŻī ĒÖśĻ▓ĮŌĆÖ ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ ļČäņäØ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ņŚÉņä£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ NOACņØś ņØ┤ļōØņØ┤ ņ×äņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ ņØ╝Ļ┤ĆļÉśĻ▓ī ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ»ĖļŻ©ņ¢┤, ņŗżņĀ£ ņ¦äļŻī ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņŚÉņä£ņØś ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäĻ░Ć ņÜ░ļĀżĒĢśņśĆļŹś ļ¦īĒü╝ ļ¦żņÜ░ ļé«ņ¦Ć ņĢŖĻ│Ā, ļīĆļץ ņĀüņĀłĒĢśņśĆņØīņØä ņČöņĀĢĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[56,62-81]. ĻĘĖļ¤╝ņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņżæļŗ©ņ£©ņØĆ NOAC ĒÖśņ×É Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņä£ ņŚ¼ņĀäĒ׳ ļ¼ĖņĀ£ņØ┤ļŗż[51,59,60,67,78,82-89]. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, NOAC ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ ņ”Øņ¦äņŗ£ĒéżĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ļ¬©ļōĀ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØä ļ¬©ļæÉ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśļ®░, ņĢäļלņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢ£ļŗż.

1) ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Āņ╣śļŻīļź╝ ļ░øļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņØĖ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĻ│╝ ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäņØś ņżæņÜöņä▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĄÉņ£ĪņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż[18,19,36,37,90,91]. 2) ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś Ļ░ĆņĪ▒ļōżļÅä ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäņØś ņżæņÜöņä▒ņØä ņØ┤ĒĢ┤ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļÅäļĪØ ĒĢśĻ│Ā ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļÅäņÜĖ ņłś ņ׳ļÅäļĪØ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢ£ļŗż. 3) NOACļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŖżņ╝ĆņżäņØä Ļ│äĒÜŹĒĢśĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ļź╝ ĒÖśņ×É Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆņŚ¼ĒĢśļŖö ļŗżļźĖ ņĀäļ¼ĖĻ░Ćļōż(ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ļŗ┤ļŗ╣ĒĢśļŖö ņŗ¼ņןļé┤Ļ│╝ ņØśņé¼, ņØ╝ļ░śņØś, ņĢĮņé¼, Ļ░äĒśĖņé¼, ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā Ēü┤ļ”¼ļŗē, ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ņ¦äļŻīĒĢśļŖö ĒāĆĻ│╝ ņØśļŻīņ¦ä ļō▒)Ļ│╝ļÅä Ļ│Ąņ£ĀĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ĒÖśņ×É Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ņŚÉ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ ļ¬©ļōĀ ņØśļŻīņ¦äņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäņŚÉ ņ▒ģņ×äņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. 4) ņØ╝ļČĆ ĻĄŁĻ░ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĢĮĻĄŁņØś ņĪ░ņĀ£ ņĀĢļ│┤ņØś ļäżĒŖĖņøīĒü¼Ļ░Ć ņל ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĀĖ ņ׳ņ¢┤ Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņ▓śļ░®ļÉśļŖö NOACņØś ņłśļź╝ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņČöņĀüĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤░ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĢĮņé¼Ļ░Ć ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅä ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üņŚÉ ņĀüĻĘ╣ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░£ņ×ģļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░ ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ│┤ļŖö ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņ▓śļ░® ļ░Å ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņØś ļīĆņĪ░ Ļ▓ĆĒåĀņŚÉ ņØ┤ņÜ®ļÉĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ╝ļČĆ ĻĄŁĻ░ĆņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĢĮņé¼ņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ņČöņĀü Ļ┤Ćņ░░Ļ│╝ ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅä ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üņØś ņ”ØĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ Ē¢źņāüņŗ£ņ╝░ļŗż[92]. 5) ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ Ē¢źņāüņŗ£ĒéżĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ£ ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ĒśĢĒā£ņØś ļ¦ÄņØĆ ĻĖ░ņłĀņĀüņØĖ ļÅäņøĆ ņןņ╣śļōżņØ┤ Ļ░£ļ░£ļÉśĻ│Ā ņĀüņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż. ĒŖ╣ņłśĒĢ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ ĒżņןņÜ®ĻĖ░ Ēś╣ņØĆ ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│┤Ļ┤Ć ņāüņ×É(ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ ļ░®ņŗØ ļśÉļŖö ļ│ĄņĢĮņØ┤ ĻĖ░ļĪØļÉśļŖö ņĀäņ×É ņןņ╣śņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ│äļÉ£ ļ░®ņŗØ) ĒśĢĒā£Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņ¢┤ņÖöĻ│Ā, ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ņŚÉļŖö ņŖżļ¦łĒŖĖĒÅ░ ņ¢┤Ēöīļ”¼ņ╝ĆņØ┤ņģśņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØä ņĢīļĀżņŻ╝ļŖö ĒśĢĒā£ņØś ļÅäņøĆ ņןņ╣śļōżļÅä ņ׳ļŗż[93]. 6) ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤Ć ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓Ģļ│┤ļŗż ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäĻ░Ć ļåÆļŗż[94-97]. ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś NOAC ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉ ņØśĒĢśļ®┤, 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ļé©ņØĆ ņĢīņĢĮ ņłś ņĖĪļ®┤ņŚÉņä£ ļŹö ņÜ░ņłśĒĢśņśĆļŗż[51,54-57,78,97-100]. ĒśłņĀä ņāēņĀäņ”Ø ņśłļ░® ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņÖĆ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ ļ│┤ņןņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ¢┤ļ¢ż ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ļŹö ņÜ░ņłśĒĢ£ņ¦ĆļŖö ļČłļČäļ¬ģĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļé«ņØĆ ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļŖö ļéśņü£ ņ×äņāüņĀü Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ļŗż[66-69,73-78,101-104]. 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņŚÉņä£ ĒĢ£ļ▓ł ļ│ĄņĢĮņØä ļåōņ╣śļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņŚÉņä£ ļæÉ ļ▓ł ļ│ĄņĢĮņØä ļåōņ╣śļŖö Ļ▓āļ│┤ļŗż ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ņ×æņÜ®ņØś ļ│ĆļÅÖņä▒ņØ┤ ļŹö Ēü┤ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī[105], ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ļ│ĆļÅÖņä▒ņØ┤ Ļ░¢ļŖö ņ×äņāüņĀü ņØśļ»ĖļŖö ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż[106]. 7) ļé«ņØĆ ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäĻ░Ć ņØśņŗ¼ļÉĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĀäņ×É ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņÜ® Ēī©Ēä┤ņŚÉ Ļ┤ĆĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ│┤ļź╝ ņ¢╗Ļ│Ā, ĒÖśņ×Éļź╝ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢśļŖöļŹ░ ļÅäņøĆņØä ņ¢╗ņØä ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņĀäņ×ÉņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņÜ® ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üņØĆ ņøÉĻ▓® ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦ü ņä£ļ╣äņŖżņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ│äļÉĀ ņłśļÅä ņ׳Ļ│Ā ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņóĆ ļŹö ļ╣ĀļźĖ Ēö╝ļō£ļ░▒ņØä ņĀ£Ļ│ĄĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[107]. 8) ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦ü ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö NOACļ│┤ļŗżļŖö INR ļ¬©ļŗłĒä░ļ¦üņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØä ņäĀĒśĖĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżļÅä ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤░ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉĻ▓īļÅä NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│Ā ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ£Āņ¦ĆļÉśļŖö ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ĻĄ░Ļ│╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ļÅä ļæÉĻ░£ļé┤ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØä ĒśäņĀĆĒ׳ ņżäņØ┤ļŖö ļō▒ņØś ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ņØś ņ×äņāüņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż[18,36]. 9) ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ĻĄÉņ£ĪĻ│╝ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ļÅäĻĄ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉļÅä ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäĻ░Ć ļé«ņØĆ NOAC ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØĆ ļŗżņŗ£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀäĒÖśņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļé«ņØĆ ļ│ĄņĢĮ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØĆ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉļÅä ņŚŁņŗ£ Ēü░ INR ļ│ĆļÅÖĒÅŁņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļ®░ ņØ┤ļŖö ļéśņü£ ņ×äņāü Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ņÖĆ ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ļŗż.

ļŗżļźĖ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļĪ£ ĻĄÉņ▓┤ĒĢĀ ļĢīļŖö ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØś ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ¦ĆņåŹņŗ£Ēéżļ®┤ņä£ ņČ£Ēśł ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØä ņżäņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ░£ļ│ä ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ņĢĮņŚŁļÅÖĒĢÖņØä Ļ░£Ļ░£ņØĖņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ▓ī ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

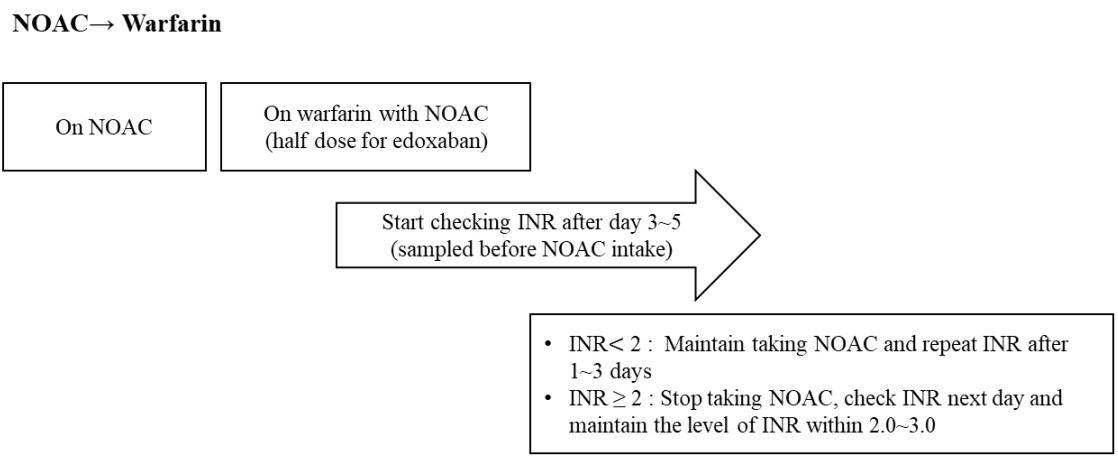

INR ņłśņ╣śĻ░Ć ņ╣śļŻī ļ¬®Ēæ£ņ╣śņØĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ NOACļĪ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņĀäĒÖśĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, NOACņØś Ēł¼ņĢĮ ņŗ£ņĀÉņØĆ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØä ņżæļŗ©ĒĢ£ Ēøä INR ņłśņ╣śņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ļŗżņØīņØś ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłņØä ļö░ļźĖļŗż(Fig. 4). ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØś ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ļŖö 36-48ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ļ»ĆļĪ£, ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņĢĮņŚŁļÅÖĒĢÖņĀü ņ¦ĆņŗØņØä ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ļĪ£ ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĢĮņĀ£ ņżæļŗ© Ēøä INRņØä ļŗżņŗ£ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢĀ ņŗ£ņĀÉņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØĆ ņ×æņÜ® ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ļŖ”ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ, ņ╣śļŻī ļ¬®Ēæ£ņØś INRņŚÉ ļÅäļŗ¼ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö 5-10ņØ╝ ņĀĢļÅäņØś ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØ┤ ņåīņÜöļÉ£ļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ NOACņŚÉņä£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņāüļŗ╣ĒĢ£ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļ®░, NOAC ņżæļŗ© ņŗ£ņĀÉņØä ņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ▓ī Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņŚÉņä£ NOACļĪ£ņØś ņĢĮņĀ£ ņĀäĒÖśņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ ĒØÉļ”äļÅäļź╝ ĻĘĖļ”╝ 5ņŚÉ ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļČĆĒĢś ņÜ®ļ¤ē(loading dose)ņØĆ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ĒĢäņÜöĻ░Ć ņŚåļŗż.

NOACļŖö INRņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ»ĆļĪ£, NOAC ļ│ĄņÜ® ņ¦üņĀäņŚÉ INRņØä ņĖĪņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņØä ņ£ĀļģÉĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ NOACņŚÉņä£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮņØä ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢ£ņ¦Ć 1Ļ░£ņøö ņØ┤ļé┤ņŚÉļŖö ņ▓ĀņĀĆĒĢśĻ▓ī INRņØä ņĖĪņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ENGAGE-AF ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ NOACņŚÉņä£ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀäĒÖśņØ┤ ņÖäļŻīļÉśļŖö ļŹ░ņŚÉļŖö ļīĆļץ 14ņØ╝ Ļ░Ćļ¤ēņØś ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØ┤ ņÜöĻĄ¼ļÉśņŚłļŗż[108]. ņĢĮņĀ£ ņĀäĒÖśņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ ĒØÉļ”äļÅäļź╝ ņżĆņłśĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢīļŖö ļćīĻ▓ĮņāēņØ┤ļéś ļćīņČ£ĒśłĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņĀüņŚłļŹś ļ░śļ®┤[108], ņżĆņłśĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒÖĢņŚ░ĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż[109,110].

NOAC ņżæļŗ© Ēøä ļÅÖņØ╝ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ļŗżņØīņŚÉ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņŗ£ņĀÉņŚÉ ļ╣äĻ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ņØĖ ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ņØä Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ļ╣äļČäĒÜŹ ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ ņżæļŗ© Ēøä 2-4ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ Ļ▓ĮĻ│╝ĒĢ£ ļÆż NOACļź╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņĀĆ ļČäņ×Éļ¤ē ĒŚżĒīīļ”░ņØĆ ņżæļŗ© Ēøä ļŗżņØī Ēł¼ņŚ¼ ņŗ£ņĀÉņŚÉ NOACļź╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņØīņŗØĻ│╝ ņĢĮņĀ£ Ļ░ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØä ņŗĀņżæĒ׳ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. NOACļŖö ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀüņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ ļÅÖļ░ś ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ░Å ĻĖ░ņĀĆ ņ¦łĒÖśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. Ļ░üĻ░ü ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ĒŖ╣ņä▒ņŚÉ ļ¦×ļŖö ņ▓śļ░®ņØä ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņØĖņ×Éļōż Ļ░äņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļÅä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀĢļ│┤Ļ░Ć ņĀÉņ░© ļ¦ÄņĢä ņ¦ÉņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ē¢źĒøäņŚÉļŖö ņāłļĪ£ņÜ┤ ņĀĢļ│┤ļōżņØ┤ Ēśäņ×¼ņØś ĻČīĻ│ĀņĢłņØä ļ│ĆĻ▓Įņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłśļÅä ņ׳ļŗż.

ļīĆļČĆļČä NOACņÖĆņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņŚÉļŖö ņ£äņןĻ┤ĆņØä ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒØĪņłśļÉ£ ļÆż P-glycoprotein (P-gp)ņØä ĒåĄĒĢ£ ņ×¼ļČäļ╣ä Ļ│╝ņĀĢņØ┤ Ļ┤ĆņŚ¼ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņØ┤ Ļ│╝ņĀĢņŚÉņä£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļōż Ļ░äņØś Ļ▓Įņ¤üņĀüņØĖ ņ¢ĄņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅä ņ”ØĻ░Ćļź╝ ņØ╝ņ£╝Ēé©ļŗż. P-gpļŖö ņŗĀņן ļ░░ņäżĻ│╝ļÅä ņŚ░Ļ┤ĆļÉ£ļŗż[111]. ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ņĢĮņĀ£ļōż ņżæ ņāüļŗ╣ņłśĻ░Ć P-gp ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØ┤ļŗż(ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░Ć, ļō£ļĪ£ļäżļŗżļĪĀ, ņĢäļ»ĖņśżļŗżļĪĀ, ĒĆ┤ļŗłļöś ļō▒). ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░śĻ│╝ ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļīĆņé¼ļŖö CYP3A4 typeņØś Cytochrome P450ņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦äļŗż[112]. Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ CYP3A4 ņ¢ĄņĀ£ļéś ņ£ĀļÅäĻ░Ć ņØ┤ļōż ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś ļ╣äļīĆņé¼ņĀü ņĀ£Ļ▒░ļŖö ļŗżņ¢æĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ×Āņ×¼ņĀüņØĖ ņĢĮļ¼╝ Ļ░ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņāüļīĆņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀüļŗż[113]. ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£, Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ P-gp Ēś╣ņØĆ CYP3A4 ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØä NOACņÖĆ ļ│æņÜ®ņØĆ ĻČīĻ│ĀļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż. ļ░śļīĆļĪ£ Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ P-gp Ēś╣ņØĆ CYP3A4 ņ£ĀļÅä ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, NOAC ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ ĒśäņĀĆĒ׳ ņĀĆĒĢśņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņĢĮņĀ£ņÖĆņØś ļ│æņÜ®ņØĆ ĻĖłĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ņŻ╝ņØś Ļ╣ŖĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

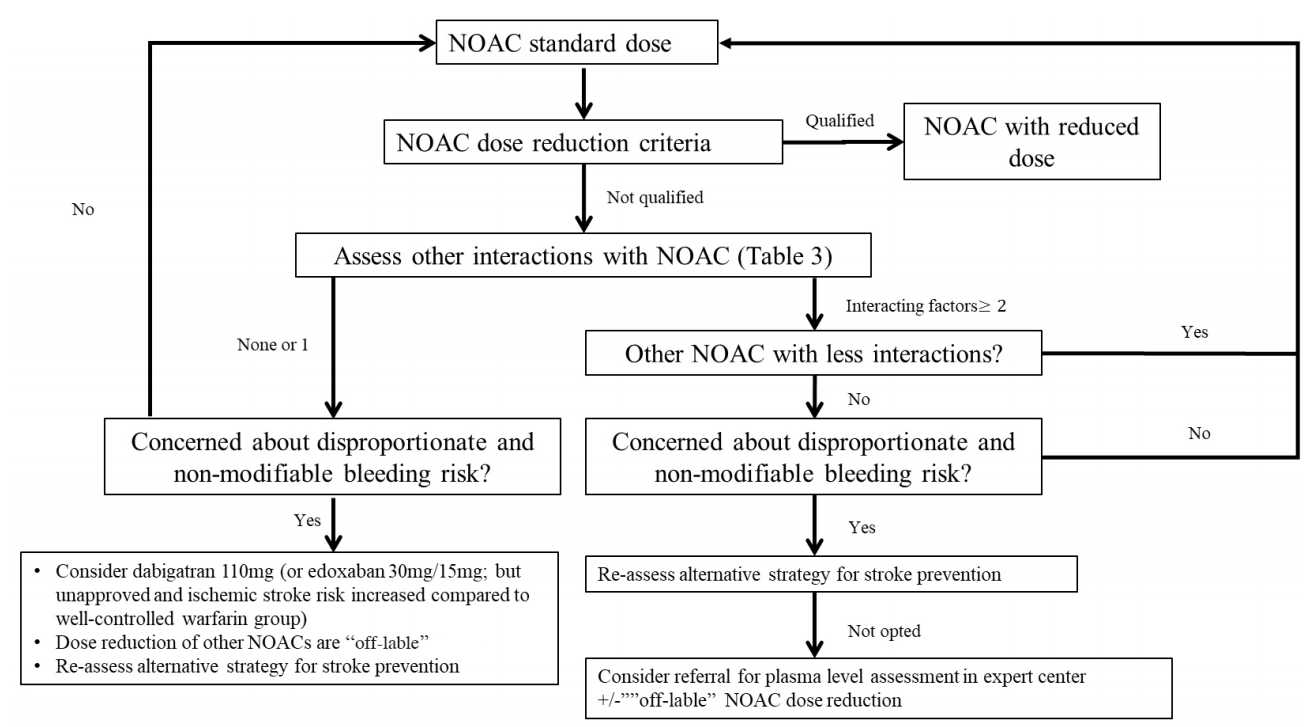

ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ NOACņØś ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĢīĻ│Āļ”¼ņ”śņØ┤ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© 3ņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ĒÅēĻ░ĆļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā, ĻĘĖ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņÖĆ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ņØ┤ ņ”Øļ¬ģļÉśņŚłļŗż. ENGAGE-AF ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļ¦ī ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░Éņåī ĻĖ░ņżĆņŚÉ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢśņŚ¼ ļČäņäØĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņŚÉ ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░Éņåī ĻĖ░ņżĆņŚÉ ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśĻ│Ā, ļÉśļÅäļĪØ ņĀĢĒĢ┤ņ¦ä ĻČīĻ│Ā ņÜ®ļ¤ēņŚÉ ļ¦×Ļ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīņןļÉ£ļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś ņČ£Ēśł ņä▒Ē¢źņØ┤ ļåÆĻ▒░ļéś ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņØĖņ×ÉļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ Ēśłņżæ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ļåÆņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņśłņāüļÉśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņŚÉņä£ļŖö NOAC ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░Éļ¤ēņØ┤ ņśżĒ׳ļĀż ĒĢ®ļ”¼ņĀüņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[17,114-117]. ņĀĆ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś NOACņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀäĒ¢źņĀü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć 110 mg ĒĢśļŻ© 2ĒÜīņÖĆ ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś 30/15 mg ĒĢśļŻ© 1ĒÜī ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļ¦ī ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć 110 mg ĒĢśļŻ© 2ĒÜī ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ņÖĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņŚ¼ ļćīņĪĖņżæ ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØĆ ļ╣äņŖĘĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā ņŻ╝ņÜö ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØĆ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢśņśĆļŗż[23]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņØ┤ļŖö ļČłĒŖ╣ņĀĢĒĢ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØ┤ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ, ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆļÉ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ņØś ņŻ╝ņÜö ņČ£Ēśł ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØś Ļ░Éņåī ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļŖö ņŚåņØä ņłśļÅä ņ׳ļŗż[115,118]. ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś 30/15 mg ĒĢśļŻ© 1ĒÜī ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņל ņĪ░ņĀłļÉśļŖö ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĻĄ░ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒŚłĒśłņä▒ ļćīņĪĖņżæņØ┤ 41% ņ”ØĻ░ĆļÉśņŚłĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ņŖ╣ņØĖļ░øņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśņśĆļŗż[24,116]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĻĄ░Ļ│╝ ļīĆļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŻ╝ņÜö ņČ£Ēśł, ņŗ¼ĒśłĻ┤ĆĻ│ä ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā ļ¬©ļōĀ ņøÉņØĖņØś ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØĆ ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś ņé¼ņÜ®ĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ Ļ░ÉņåīļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē NOAC ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļćīņĪĖņżæ ņśłļ░® ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļ¦ī ĒĢ┤ņäØņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļŗż[23,34]. ļ░śļ®┤, ROCKET-AFļéś ARISTOTLE ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ēĻĄ░ņØ┤ ĒżĒĢ©ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢä Ļ░Éļ¤ēļÉ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņĀĢļ│┤Ļ░Ć ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀüņØ┤ļŗż[119]. ļīĆļŗżņłśņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ŌĆ£off-lableŌĆØļĪ£ ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ņ▓śļ░®ņØĆ ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņØ┤ņ£ĀņŚÉņä£ ņ¦Ćņ¢æļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņŗżņĀ£ļĪ£, ņČ£Ēśł Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØä ļåÆņØ┤ļŖö ņØĖņ×ÉļōżņØ┤ ļćīņĪĖņżæņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉņØĖ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦ÄņĢä(Ļ│ĀļĀ╣, ļģĖņćĀĒĢ© ļō▒) ļČĆņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ▓ī Ļ░Éļ¤ēļÉ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ļćīņĪĖņżæņØś ņśłļ░® ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņČ®ļČäņ╣ś ļ¬╗ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[120]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ĒŖ╣ņĀĢĒĢ£ ņĢĮļ¼╝ Ļ░ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ® Ēś╣ņØĆ ĒŖ╣ņłśĒĢ£ ĻĖ░ņĀĆ ņ¦łĒÖśņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö ĒÖśņ×É(ņןĻĖ░ ņØ┤ņŗØ ĒÖśņ×É, HIV ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ņżæņØĖ ĒÖśņ×É)ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļō£ļ¼╝Ļ▓ī NOACņØś Ļ░Éļ¤ē Ēś╣ņØĆ ņżæļŗ© ļō▒ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż(Fig. 6). ņØ┤ļ¤░ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ĒŖ╣ņłśĒĢ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ļéś NOACņØś Ļ▓ĮĒŚśņØ┤ ĒÆŹļČĆĒĢ£ ņØśļŻī ĻĖ░Ļ┤ĆņŚÉņä£ Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņÜöņĢĮĒĢśņ×Éļ®┤, NOACņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ņżä ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņĢĮļ¼╝ Ļ░äņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ļéś ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ĒŖ╣ņłśĒĢ£ ņ×äņāü ņāüĒÖ®Ļ│╝ ļÅÖļ░śļÉ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉļ¦×ņČ░ņä£ NOACļź╝ ņĀüņĀłĒ׳ ņ▓śļ░®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ļŗżņØīņØś Ēæ£ 3ņØĆ NOACņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣Ā ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņĢĮņĀ£ļōżņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĀĢļ”¼ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņØĖņ×ÉļōżĻ│╝ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļōżņØä ļ░öĒāĢņ£╝ļĪ£ NOACņØś ņäĀĒāØ ļ░Å ĻĘĖ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤╝ņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņŗżņĀ£ļĪ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśļŖö ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņāüļŗ╣ņłśņØś ņĢĮņĀ£ļōżņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņĀĢļ│┤Ļ░Ć ļ»Ėļ»ĖĒĢśļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņØä ņŚ╝ļæÉĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś 15 mg/20 mgņØĆ ļŗżļźĖ NOACņÖĆ ļŗ¼ļ”¼ ņØīņŗØļ¼╝Ļ│╝ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ņäŁņĘ©ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, PPIļéś H2 blockerņÖĆ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļ®┤ ņāØņ▓┤ ņØ┤ņÜ®ļźĀņØ┤ ņĢĮĻ░ä Ļ░ÉņåīļÉśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņ×äņāüņĀü ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņŚÉļŖö ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņŚåļŗż[121,122]. ļŗżļźĖ NOACņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņĀ£ņé░ņĀ£ņÖĆņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØĆ ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[123-125]. Fish oilĻ│╝ņØś ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖņĀü ņ×ÉļŻīļŖö ņŚåņ£╝ļéś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØĆ ņŚåņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØĻ░üļÉ£ļŗż. ļ╣äņ£äĻ┤ĆņØä ĒåĄĒĢ£ ļČäļ¦É ĒśĢĒā£ Ēł¼ņĢĮņØĆ ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś, ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņŚÉņä£ ņāØņ▓┤ ņØ┤ņÜ®ļźĀņŚÉ ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņŚåļŗż[126-128]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØĆ ņ║ĪņŖÉņØä ņĀ£Ļ▒░ĒĢśĻ│Ā Ļ░ĆļŻ©ļź╝ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØĆ ņāØņ▓┤ ņØ┤ņÜ®ļźĀņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż.

Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØĆ Ēæ£ 3ņŚÉ ļ¬ģņŗ£ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░ĆņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś P-gp ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļŖö ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░ĆņØś ņä▒ņāüņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢśļŗż. ņ”ēĒÜ©ĒśĢņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ćļ│┤ļŗż ĒĢ£ ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņĀäņŚÉ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļ®┤ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ 180%ļĪ£ ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤░ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĢĮ Ēł¼ņĢĮ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØä ļæÉ ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢśļ®┤ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØĆ ņŚåņ¢┤ņ¦äļŗż. ņä£ļ░®ĒśĢ ņĀ£ņĀ£ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć ļåŹļÅäņØś 60%ļź╝ ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż.

RE-LY ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░ĆņØä ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ĒÅēĻĘĀ 23% ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢ£ļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā[129], ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░Ć ļ│ĄņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļÅäļĪØ ĻČīĒĢ£ļŗż. ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śļÅä ņ┤łĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØĻ░üļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļéś[130], 3ņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ļČäņäØ ĒøäņŚÉļŖö ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØśļ»ĖĻ░Ć ņŚåņØīņØ┤ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņ¢┤, ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░ÉņåīļŖö ĻČīņןļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś ļŗżļźĖ ņÜöņØĖļōżĻ│╝ņØś ņāüĻ┤Ć Ļ┤ĆĻ│äĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖöņ¦Ć ņŻ╝ņØśļź╝ ĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØ┤ļéś ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░śņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░ĆņØś ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖņĀüņØĖ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØĆ ņĢīļĀżņ¦ä ļ░öĻ░Ć ņŚåļŗż.

ļö£Ēŗ░ņĢäņĀ¼ņØĆ P-gp ņ¢ĄņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ļé«ņĢä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņĀüļŗżĻ│Ā ņĢīļĀżņĪīņØīņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā[129], ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ 40% ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé©ļŗż[131]. ņĀĢņāü ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņĢäļ»ĖņśżļŗżļĪĀņØĆ ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś AUCļź╝ 40% ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé©ļŗż[132]. 3ņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śĻ│╝ ņĢäļ»ĖņśżļŗżļĪĀ Ļ░äņŚÉļŖö ņāüļŗ╣ĒĢ£ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ׳ņ¢┤ Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöņŚÉļÅä ņśüĒ¢źņØ┤ ņ׳ņØä ņłś ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØĻ░üļÉ£ļŗż[133]. ĻĘĖļ¤╝ņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā, ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ņ▓śļ░®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļÅä ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś Ļ░ÉņåīļŖö ĻČīņןļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż.

ļō£ļĪ£ļäżļŗżļĪĀņØĆ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäņŚÉ Ēü░ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ»Ėņ╣śļ»ĆļĪ£, ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØĆ ĻĖłĻĖ░ņØ┤ļŗż. ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļÅä ņżæļō▒ļÅäņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņ׳ņ¢┤ ļō£ļĪ£ļäżļŗżļĪĀņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ENGAGE-AFņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņżäņØ┤ļŖö ĻĖ░ņżĆņØ┤ ļÉ£ļŗż[24]. ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░śĻ│╝ ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņ¦ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņŚåņ£╝ļéś, P-gpņÖĆ CYP3A4 ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØä ĻĘ╝Ļ▒░ļĪ£ ņŻ╝ņØśļź╝ ņÜöĒĢ£ļŗż[134]. ĒØźļ»ĖļĪŁĻ▓īļÅä ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ NOAC ļ│ĄņÜ® ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņłśņłĀņĀü ņ╣śļŻī ņĀä, ļ▓ĀļØ╝Ēīīļ░Ć, ļō£ļĪ£ļäżļŗżļĪĀ ļśÉļŖö ņĢäļ»ĖņśżļŗżļĪĀņØä ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, NOACņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ļåÆņĢśļŗż[135].

ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ NOACļŖö CYPļéś P-gp/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)ņØä ņ£ĀļÅäĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż. ņØ┤ļōż ļīĆņé¼ļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ļ»ĖļŗżņĪĖļ×ī(CYP3A4), ļööĻ│ĪņŗĀ(P-gp), ņĢäĒåĀļ░öņŖżĒāĆĒŗ┤(P-gp, CYP3A4)Ļ│╝ņØś ļ│æņÜ® Ēł¼ņĢĮņØ┤ ņØ┤ļōż ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśĻ▓ī ļ│ĆĒÖöņŗ£Ēéżņ¦ĆļŖö ņĢŖļŖöļŗż.

ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ņØĖ Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼(ticagrelor)ļŖö P-gp ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ņØ┤ļŗż. ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć 110 mgĻ│╝ Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņØś ļ│æņÜ® Ēł¼ņĢĮņØĆ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć ļŗ©ļÅģ Ēł¼ņĢĮņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Cmaxļź╝ 65%Ļ╣īņ¦Ć ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé©ļŗż. ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć Ēł¼ņŚ¼ Ēøä ļæÉ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØś Ēł¼ņĢĮ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØä ļæÉĻ│Ā Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ 180 mgņØä Ēł¼ņĢĮĒĢśņśĆņØä ļĢīņŚÉļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś CmaxņÖĆ AUC ņ”ØĻ░ĆĻ░Ć Ļ░üĻ░ü 23%ņÖĆ 27%ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż[136]. Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņØś ļČĆĒĢś ņÜ®ļ¤ē ļ│ĄņÜ®ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢĀ ļĢīļŖö ņØ┤ņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ Ēł¼ņĢĮ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØä ĻĖĖĻ▓ī ĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĒĢ£ļŗż. Ēŗ░ņ╣┤ĻĘĖļĀÉļ¤¼ņÖĆ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć 110 mgņØä ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć ļŗ©ļÅģ ļ│ĄņÜ®ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś AUCņÖĆ CmaxĻ░Ć Ļ░üĻ░ü 26%, 29% ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņØ┤ļŖö RE-DUAL PCIņŚÉņä£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż. ĻĘĖ ņÖĖ ņĢĮņ┤łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ Ļ│╝ņåī ĒÅēĻ░ĆļÉśļŖö Ļ▓ĮĒ¢źņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. St. JohnŌĆÖs wortļŖö Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ CYP3A4Ļ│╝ P-gp ņ£ĀļÅäņĀ£ņØ┤ļ®░, NOAC ļåŹļÅäļź╝ Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£Ēé¼ Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼[137] NOACņÖĆņØś ļ│æņÜ® ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ĻČīņןļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż.

ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖņĀü ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®Ļ│╝ ņāüĻ┤Ć ņŚåņØ┤ ļŗżļźĖ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£, ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£, NSAIDsņØś ļ│æņÜ®ņØĆ ņČ£ĒśłņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£Ēé©ļŗż[138-140]. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£, ņØ┤ļ¤░ ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ļ│æņÜ®ņØĆ ņØ┤ļōØņØ┤ ņČ£Ēśłļ│┤ļŗż ļåÆļŗżĻ│Ā ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņŻ╝ņØśĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĀĖņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. NOACņÖĆ ļæÉ Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆņØś ĒĢŁĒśłņåīĒīÉņĀ£ļź╝ ļ│æņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö 3ņĀ£ ņÜöļ▓Ģ ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØĆ ņĄ£ļīĆĒĢ£ ĻĖ░Ļ░äņØä ņżäņØ┤ļŖö ļō▒ņØś ņĪ░ņ£©ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż.

ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņÜ®ņØĆ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢ£ ļČĆņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņל ņāØĻĖ░ļŖö ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉņØ┤ļŗż[141-143]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ROCKET-AFņÖĆ ARISTOTLEņŚÉņä£, 5Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć Ēś╣ņØĆ 9Ļ░Ćņ¦Ć ņØ┤ņāüņØś ļŗżņĢĮņĀ£ļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×Éļōż ņŚŁņŗ£ NOACļŖö ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ņÖĆ ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢ£ ņ×äņāü Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż[142,143]. ņØ┤ļ¤░ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ĒĢ┤ņäØņŚÉ ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ņé¼Ēøä ļČäņäØņŚÉņä£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłĻ│Ā, ļŗżņĢĮņĀ£ ņżæņŚÉņä£ļÅä Ļ░ĢļĀźĒĢ£ CYP3A4 ņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£(ketoconazole, ritonavir) ļśÉļŖö ņ£ĀļÅäņĀ£(phenytoin, rifampicin)ņÖĆņØś ļ│æņÜ®ņØĆ ĻĖłĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ļŗżņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņÜ® ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņ×äņāü ņé¼Ļ▒┤ņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņśĆļŖöļŹ░ ņØ┤ļŖö ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ļ┐Éļ¦ī ņĢäļŗłļØ╝, ņØ┤ļ¤░ ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØ┤ ĻĖ░ļ│ĖņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ņØ┤ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ĻĖ░ļÅä ĒĢśļŗż. ļŗżņĢĮņĀ£ ļ│ĄņÜ®ļĀźņØ┤ NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņØś ĻĖłĻĖ░ļŖö ņĢäļŗłņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņØ┤ļ¤░ Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĒŖ╣ļ│äĒ׳ ņŻ╝ņØśĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż.

ņŗĀņן ļ░Å Ļ░ä ĻĖ░ļŖźņØĆ NOACņØś ļīĆņé¼ ļ░Å ļ░░ņäżņŚÉ ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņŚŁĒĢĀņØä ĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ NOAC ņé¼ņÜ® ļ░Å ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ▓░ņĀĢņŚÉ ļ░śļō£ņŗ£ Ļ│ĀļĀżļÉśņ¢┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņØĆ ļ¦īņä▒ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖśņØś ļ░£ņāØĻ│╝ ņ¦äĒ¢ēņØä ņ£Āļ░£ĒĢśļ®░, ļ¦īņä▒ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØ┤ ņĀĆĒĢśļÉĀņłśļĪØ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖņØś ņ£Āļ│æļźĀ ļ░Å ļ░£ņāØļźĀņØ┤ ņāüņŖ╣ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[144-147]. ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖśņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö ņāēņĀäņ”Ø ļ░Å ņŗ¼Ļ░üĒĢ£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ļ¬©ļæÉĻ░Ć ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØ┤ĒÖśņ£© ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£ĒéżĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ņśłņĖĪ ļ░Å ņ╣śļŻīĻ░Ć ņēĮņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż[148,149]. ĒśäņĪ┤ĒĢśļŖö 4Ļ░£ņØś NOAC ļ¬©ļæÉ ņØ╝ņĀĢ ļČĆļČä ņŗĀņןņØä ĒåĄĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░░ņäżļÉśļŖöļŹ░, ĻĘĖ ļ╣äņ£©ņØĆ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć(80%), ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś(50%), ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś(35%), ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś(27%) ņł£ņØ┤ļŗż(Table 4).

ļ¦īņä▒ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖśņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī Ļ▓ĮĻĄ¼ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ļź╝ ņ▓śļ░®ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņĀä ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØś ĒÅēĻ░ĆņŚÉļŖö ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ Ļ│ĄņŗØņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖöļŹ░, Ļ░üĻ░üņØś Ļ│ĄņŗØļ¦łļŗż ņןņĀÉĻ│╝ ļŗ©ņĀÉļōżņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. CKD-EPI Ļ│ĄņŗØņØĆ National Kidney FoundationņŚÉņä£ ĻČīņןĒĢśļŖö Ļ│ĄņŗØņ£╝ļĪ£, ļ¬©ļōĀ ļ▓öņ£äņØś ļ¦īņä▒ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ļŗ©Ļ│äņŚÉņä£ ņŗĀļó░ļÅäĻ░Ć ļåÆņØĆ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[150]. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ņ׳ņ¢┤ņä£ļŖö Cockcroft-Gault ļ░®ņŗØņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź Ļ│äņé░(creatinine clearance, CrCl)ņØä ņŻ╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉśļŖöļŹ░, ņØ┤ļŖö ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś NOAC 3ņāü ļīĆĒæ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ ņØ┤ ļ░®ņŗØņØ┤ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśņŚłĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļ¼┤ņŚćļ│┤ļŗż ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņĀÉņØĆ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØś Ļ│äņé░ņØ┤ ņ¢┤ļ¢ż Ļ│ĄņŗØņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦ĆļŖöņ¦Ć ļ│┤ļŗż ĻĖēņä▒ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö ņāüĒā£Ļ░Ć ņĢäļŗī ņĢłņĀĢņĀüņØĖ ņāüĒā£ņŚÉņä£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØś ĒÅēĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĀĖņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņØ┤ļŗż.

ļśÉĒĢ£ NOACļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØĆ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĪ░ĻĖ░ Ļ░Éņ¦Ćļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĄ£ņåīĒĢ£ 1ļģä Ļ░äĻ▓®ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĒÅēĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņĀĖņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļ¦īņĢĮ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśĻ░Ć ņØ┤ļ»Ė ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░(CrCl < 60 mL/min)ņŚÉļŖö ļŹö ņ¦¦ņØĆ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ĒÅēĻ░ĆĻ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ļŹ░, ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś CrClļź╝ 10ņ£╝ļĪ£ ļéśļłł Ļ░ÆņØ┤ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź Ļ▓Ćņé¼ņØś Ļ░äĻ▓®(Ļ░£ņøö)ņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻČīņןļÉ£ļŗż(ņśł: CrCl 30 mL/minņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ 3Ļ░£ņøöņŚÉ ĒĢ£ ļ▓łņö® Ļ▓Ćņé¼ ĻČīņן). ļśÉĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻ░Ć Ļ│ĀļĀ╣, ļģĖņćĀ, ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ļÅÖļ░ś ņ¦łĒÖś ļō▒ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ņ£äĒŚśņØĖņ×ÉļōżņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆĻ│Ā ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ņŻ╝ņØś ļ░Å ņ¦¦ņØĆ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź Ļ▓Ćņé¼Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņŗĀņן ļ░░ņäż ļ╣äņ£©ņØ┤ ļåÆĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ Ļ░üļ│äĒĢ£ ņŻ╝ņØśĻ░Ć ņÜöĻĄ¼ļÉ£ļŗż.

ĻĘĖ ņÖĆļŖö ļ░śļīĆļĪ£, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņØ┤ ĒÅēĻĘĀ ņØ┤ņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåÆņØĆ ĒÖśņ×É(CrCl > 95 mL/min)ņŚÉņä£ ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░ś(60 mg 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī)ņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ĻĘĖ ĒÜ©ļŖźņØ┤ Ļ░ÉņåīĒĢ£ļŗżļŖö Ļ┤Ćņ░░ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņŻ╝ņØśĻ░Ć ņÜöĻĄ¼ļÉśļ®░, ļ»ĖĻĄŁ Food and Drug Administration (FDA)ņŚÉņä£ļŖö 2015ļģä ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØä CrClņØ┤ ļåÆņØĆ(> 95 mL/min) ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļŗżļźĖ NOACļĪ£ ļ│ĆĻ▓ĮĒĢśņŚ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ļŗż[24]. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĒØźļ»ĖļĪŁĻ▓īļÅä ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś[151]ņØ┤ļéś ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś[152]Ļ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ Factor Xa inhibitor Ļ│äņŚ┤ņØś NOACļōżņŚÉņä£ ļ¬©ļæÉ ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢśĻ▓ī ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ Ē¢źĒøä ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤╝ņŚÉļÅä ļČłĻĄ¼ĒĢśĻ│Ā ENGAGE AF ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ņé¼Ēøä ļČäņäØņŚÉ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś ņĢłņĀäņä▒ ļ░Å ņĀäļ░śņĀüņØĖ ņ×äņāü Ēś£ĒāØ(net clinical benefit)ņØĆ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ņØ╝Ļ┤ĆņĀüņØĖ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗżļŖö ņĀÉ[153], ĻĄŁļé┤ļź╝ ļ╣äļĪ»ĒĢ£ ņĢäņŗ£ņĢä ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØś ņ▓┤Ļ▓® ļ░Å CrClņØ┤ ņä£ĻĄ¼ņÖĆļŖö ņāüļŗ╣ĒĢ£ ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņĢ×ņä£ ņ¢ĖĻĖēĒĢ£ ņä£ĻĄ¼ņØś ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉ ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢśĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ļ¼┤ļ”¼Ļ░Ć ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢĀ ļĢī ĻĄŁļé┤ ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ļź╝ ĻĖ░ļ░śņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļåÆņØĆ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ĻČīĻ│Ā ņé¼ĒĢŁņØĆ ņĢäņ¦ü ņŚåļŗż.

ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£Ļ░Ć Ļ▓ĮļÅä ļ░Å ņżæņ”ØļÅäņØś ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖśņØä ļÅÖļ░śĒĢ£ ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ļćīĻ▓Įņāē ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£Ēé©ļŗżļŖö Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ņØ┤ļ»Ė ņל ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż[154-157]. ņØ┤ņÖĆ ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢśĻ▓ī 4Ļ░£ņØś NOAC ļ¬©ļæÉ 3ņāü ņ×äņāü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ Ļ▓ĮļÅä ļ░Å ņżæņ”ØļÅäņØś ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ņØ╝Ļ┤ĆņĀüņØĖ ĒÜ©ļŖź ļ░Å ņĢłņĀäņä▒ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤Ļ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż[153,158-161]. ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ARISTOTLE ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś ļČäņäØ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ņŚÉņä£ļŖö CrCl Ļ░ÆņØ┤ ļé«ņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ļćīĻ▓Įņāē Ļ░Éņåī ĒÜ©ļŖźņØĆ ņ£Āņ¦ĆļÉśļ®┤ņä£ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅä Ļ░ÉņåīņØś ņĀĢļÅäĻ░Ć ļŹö ļæÉļō£ļ¤¼ņ¦ĆļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉ£ļŗż[149,161]. ļ░śļ®┤ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć 110 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņŚÉņä£ ļ│┤ņśĆļŹś ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśļÅäņØś Ļ░ÉņåīļŖö CrCl < 50 mL/min ļ»Ėļ¦īņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉ£ļŗż[160].

ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś, ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ░üĻ░üņØś 3ņāü ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļīĆņĪ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśņśĆļŹś Ļ▓āņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś ņ×äņāüņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØĖ RE-LY ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ Ļ░Éļ¤ē ņŚåņØ┤ 150 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢĻ│╝ 110 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØä ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļ░░ņĀĢĒĢśņŚ¼ ĻĘĖ ņ×äņāü Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļ®░, Ēśäņ×¼ ņĢĮĒÆł ņ▓śļ░® ņäżļ¬ģņä£ņŚÉņä£ļŖö CrCl < 50 mL/minņØ┤ļ®┤ņä£ ņČ£ĒśłņØś Ļ│Āņ£äĒŚśĻĄ░ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ļŖö 110 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØä ĻČīņןĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļź╝ ļ░śņśüĒĢśņŚ¼ ļīĆĒĢ£ļČĆņĀĢļ¦źĒĢÖĒÜī ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒĢŁņØæĻ│ĀņĀ£ ņäĀĒāØ ļ░Å ņÜ®ļ¤ē ĻČīĻ│Ā ņ¦Ćņ╣©ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ 110 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØä ĻČīĻ│ĀĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŗż(Fig. 7).

ĒĢ£ĒÄĖ ņĀüņĀłņ╣ś ļ¬╗ĒĢ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØś NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© ŌĆśreal-worldŌĆÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ņóŗņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ ņśłĒøäļź╝ ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśĻ░Ć ļ¬ģĒÖĢĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ņĀüņĀłņ╣ś ļ¬╗ĒĢ£ ņĀĆņÜ®ļ¤ē NOACņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņŗ£ ņČ£Ēśł Ļ░ÉņåīņØś ņןņĀÉņØĆ ļÜ£ļĀĘĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņ£╝ļ®┤ņä£ ļćīĻ▓Įņāē ņ£äĒŚśņä▒ļ¦ī ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ▓░ņĀĢņØĆ ņ×äņāüņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ¦żņÜ░ ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņé¼ņĢłņØ┤ļØ╝ ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳Ļ▓Āļŗż[162].

ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś NOAC ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļīĆņĪ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ļŖö CrCl < 30 mL/min ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ļōżņØä ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢśņśĆĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ(ļŗ©, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņåīņłśņØś CrCl 25-30 mL/min ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ ĒżĒĢ©) ņØ┤ ĻĄ¼Ļ░äņØś ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢśļź╝ Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļīĆņĪ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░ļŖö ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖöļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£, ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļśÉĒĢ£ ņØ┤ ĻĄ¼Ļ░äņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ņĀäĒ¢źņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉ£ ļ░öļŖö ņŚåļŖö ņāüĒā£ņØ┤ļŗż. ņØ┤ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ ĻĖłĻĖ░ņØ┤ļ®░, ņØ┤ļź╝ ņĀ£ņÖĖĒĢ£ ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśņŚ¼ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņŖ╣ņØĖļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż(Fig. 6). Ļ░ü ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ņĢĮļĀźĒĢÖ/ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖ ļ░Å ņŗĀļ░░ņäż ļ╣äņ£©, ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ņĀĆĒĢś ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉ£ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ņØä Ļ│ĀļĀżĒĢĀ ļĢī ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ļŖö ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś ļśÉļŖö ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØ┤ ņäĀĒśĖļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļéś ņČöĻ░ĆņĀüņØĖ ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļīĆņĪ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż.

ļ¦ÉĻĖ░ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖśņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ņŗ¼ļ░®ņäĖļÅÖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ņØś ĒÜ©ļŖźĻ│╝ ņ×äņāüņĀü ņØ┤ņØĄņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ņĢäņ¦üĻ╣īņ¦Ć ļģ╝ļ×ĆņØ┤ ļ¦ÄņØĆļŹ░, ņØ┤ļŖö ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ņØś ļćīĻ▓Įņāē Ļ░Éņåī ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļŖö ļČäļ¬ģĒĢśļéś ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņä▒ņØ┤ ĻĖēĻ▓®Ē׳ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņØ┤ļŗż[154,155,157]. Ēł¼ņäØņØä ļ░øļŖö ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ņØś ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ņØś ĒÜ©ņÜ®ņä▒ņØä ņĪ░ņé¼ĒĢ£ ņ£ĀņØ╝ĒĢ£ ļō▒ļĪØ Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀ ļō▒ņØä ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĀäļ░śņĀüņØĖ ņ×äņāü Ēś£ĒāØ(net clinical benefit)ņØ┤ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśļŗż[154]. ļ¦ÉĻĖ░ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢ┤ņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ ņé¼ņŗżņØĆ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£Ļ░Ć ļ¦Éņ┤łļÅÖļ¦ź ļō▒ ĒśłĻ┤ĆņŚÉ ņäØĒÜīĒÖöļź╝ ņ£Āļ░£ĒĢśļŖö ņ╣śļ¬ģņĀüņØĖ ĒĢ®ļ│æņ”ØņØä ņ£Āļ░£ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗżļŖö ņĀÉņØ┤ļŗż[163-165].

ĒĢ£ĒÄĖ, ļ¦ÉĻĖ░ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ļ░Å Ēł¼ņäØ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ņØś NOACņØś ĒÜ©ļŖźĻ│╝ ņĢłņĀäņä▒ ņŚŁņŗ£ ņ×ģņ”ØļÉśņ¦Ć ņĢŖņĢśņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ NOACņØś ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ ĻĖłĻĖ░ņØ┤ļŗż. ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ Ēł¼ņäØ ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī(FDA ņŖ╣ņØĖ ņŚåņØ┤) ņ▓śļ░®ļÉ£ ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś ļ░Å ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä ņ×ģņøÉņ£© ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä ņ”ØĻ░Ćņŗ£ĒéżļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ļŗż[166].

ļ░śļ®┤ ļ»ĖĻĄŁ(ņ£Āļ¤ĮņØĆ ĒĢ┤ļŗ╣ ņŚåņØī)ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ņĢĮļĀźĒĢÖ/ņĢĮļÅÖĒĢÖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ░ĖĻ│ĀĒĢśņŚ¼ ņŗĀļ░░ņäż ļ╣äņ£©ņØ┤ Ļ░Ćņן ņĀüņØĆ NOACņØĖ ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØś 5 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ Ēśäņ×¼ Ēł¼ņäØ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉņä£ ļ»ĖĻĄŁ FDAņØś ĒŚłĻ░Ćļź╝ ļ░øņØĆ ņāüĒā£ņØ┤ļŗż. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļéś 5 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ 2.5 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ļŹö Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäĻ░Ć ĒĢ®ļŗ╣ĒĢśļŗżļŖö ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ׳ļŗż[167]. ļ░śļ®┤ ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ņŚÉļŖö 5 mg 1ņØ╝ 2ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓ĢņØ┤ ļćīĻ▓Įņāē/ņĀäņŗĀņāēņĀäņ”Ø ņ£äĒŚśļÅä ļ░Å ņé¼ļ¦ØļźĀņØä ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ ļīĆļ╣ä Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£Ēé©ļŗżļŖö ĒøäĒ¢źņĀü ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ļ░£Ēæ£ļÉ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ņ¢┤[168], ņĢäņ¦üĻ╣īņ¦Ć ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļŗĄņØĆ ņŚåļŗż. ļŗżļźĖ NOACņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░, ļ¦ÉĻĖ░ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉņä£ņØś ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅäļź╝ ļ│┤ņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņĢĮļ¼╝ņØś ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ 15 mg 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī, ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö 10 mg 1ņØ╝ 1ĒÜī ņÜ®ļ▓Ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż[169,170].

ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņĀÉņØĆ Ēśłņżæ ļåŹļÅä ļ░Å Ļ┤Ćņ░░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ņ░ĖĻ│Ā ņ×ÉļŻīņŚÉ ļČłĻ│╝ ĒĢśļ®░, NOACļź╝ ļ¦ÉĻĖ░ ņŗĀņ¦łĒÖś ĒÖśņ×ÉņŚÉĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ┤ņä£ļŖö ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļź╝ ĒåĄĒĢ£ ņ×äņāüņĀü ņØ┤ļōØņØ┤ ļ░ØĒśĆņĀĖņĢ╝ ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØ┤ļØ╝ļŖö ņĀÉņØ┤ļŗż. Ēśäņ×¼ ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░śņØä ļīĆņāüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ 2Ļ░£ņØś ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ņ¦äĒ¢ē ņżæņØ┤ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĻĘĖ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņŻ╝ļ¬®ļÉ£ļŗż.

ņŗĀņØ┤ņŗØņØä ļ░øņØĆ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉņä£ņØś NOAC ņé¼ņÜ®ņØĆ Ēśäņ×¼Ļ╣īņ¦Ć ļŹ░ņØ┤Ēä░Ļ░Ć ņŚåņ£╝ļ®░, ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░ņŚÉĻ▓ī NOACļź╝ ņ▓śļ░®ĒĢĀ ļĢīņŚÉļŖö ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźņŚÉ ļ¦×ņČöņ¢┤ ņÜ®ļ¤ēņØä Ļ▓░ņĀĢĒĢśļÉś ļīĆļČĆļČäņØś ĒÖśņ×ÉļōżņØ┤ ļ®┤ņŚŁņ¢ĄņĀ£ņĀ£ļź╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳ĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņĢĮņĀ£ Ļ░ä ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņŚÉ ņŻ╝ņØśĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉ£ Ļ░äņ¦łĒÖśņØĆ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņä▒ņØä ļåÆņØ╝ļ┐É ņĢäļŗłļØ╝ ĒśłņĀä ņāØņä▒ņØä ņ┤ēņ¦äņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[171]. ļśÉĒĢ£ Ļ░ä ļ░░ņäż ļ░Å ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļīĆņé¼ņŚÉ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ņŻ╝ņ¢┤ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ļ░śņØæņØä ļ│ĆĒÖöņŗ£Ēéżļ®░ ņĢĮļ¼╝ ņ£Āļ░£ Ļ░ä ņåÉņāüņØä ņ£Āļ░£ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż[172]. ļśÉĒĢ£ ņ¦äĒ¢ēļÉ£ Ļ░äņ¦łĒÖś ļ░Å ņØæĻ│Ā ņןņĢĀļź╝ Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉļŖö INR ņłśņ╣śĻ░Ć ņ×Éņ▓┤ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāüņŖ╣ļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦ÄņĢä ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ļź╝ ņ▓śļ░®ĒĢĀ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņĀüņĀłĒĢ£ ņÜ®ļ¤ē ņĪ░ņĀłņØ┤ ņēĮņ¦Ć ņĢŖņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦Äļŗż[173]. ļ¬ģļ░▒ĒĢ£ ĒÖ£ļÅÖņä▒ Ļ░äņ¦łĒÖśņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä ĒÖśņ×ÉĻĄ░, ņ”ē Ļ░äĻ▓Įļ│ĆņØ┤ ņ׳Ļ▒░ļéś ņ¦ĆņåŹņĀüņØĖ Ļ░äņłśņ╣ś ļ░Å ĒÖ®ļŗ¼ ņłśņ╣śņØś ņāüņŖ╣ņØä ļ│┤ņØ┤ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļīĆĻĘ£ļ¬© NAOC 3ņāü ļ¼┤ņ×æņ£ä ļīĆņĪ░ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ ņĀ£ņÖĖļÉśņŚłļŗż[21,23,24,174]. ĻĘĖļ¤¼ļ»ĆļĪ£ 4Ļ░£ņØś NOAC ļ¬©ļæÉ Child-Truscott-Pugh CņØś Ļ░äĻ▓Įļ│Ć ļō▒ ņØæĻ│Ā ņןņĢĀ ļ░Å ļåÆņØĆ ņČ£Ēśł ņ£äĒŚśņä▒ņØä Ļ░Ćņ¦ä Ļ░äņ¦łĒÖśņŚÉņä£ļŖö ĻĖłĻĖ░ņØ┤ļŗż(Table 5). Child B Ļ░äĻ▓Įļ│Ć ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ”¼ļ░öļĪØņé¼ļ░ś ņé¼ņÜ®ņ£╝ļĪ£ Ļ░ä ņłśņ╣ś ņāüņŖ╣ņØ┤ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĻĖłĻĖ░ņØ┤ļ®░[175], ļŗżļ╣äĻ░ĆĒŖĖļ×Ć, ņĢäĒöĮņé¼ļ░ś ĻĘĖļ”¼Ļ│Ā ņŚÉļÅģņé¼ļ░śņØś Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ļŖö ņŻ╝ņØś ĒĢśņŚÉ Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśņŚ¼ Ēł¼ņŚ¼ĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņØ┤ ĻČīĻ│ĀļÉ£ļŗż. 2006ļģäņŚÉ Ļ░ä ļÅģņä▒ņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ ximelagatranņØ┤ ņŗ£ņןņŚÉņä£ Ēć┤ņČ£ļÉśņŚłĻĖ░ņŚÉ NOACņØś Ļ░ä ļÅģņä▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņÜ░ļĀżĻ░Ć ņ׳ņŚłņ£╝ļéś[176], NOAC ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņŚÉņä£ Ļ░ä ļÅģņä▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļŖö ņŚåņŚłĻĖ░ņŚÉ ņŗżņĀ£ņĀüņØĖ NOACņØś Ļ░ä ļÅģņä▒ņØĆ ļ╣äĒāĆļ»╝ K ĻĖĖĒĢŁņĀ£ļ│┤ļŗż ļé«ņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņāØĻ░üļÉ£ļŗż[177,178].

NOACļŖö ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ņēĮĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŗż. ĒĢśņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ļÅäņøĆņØ┤ ļÉśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņØĖņ¦Ć ņÜ░ņäĀ ņĀüņØæņ”ØņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĒÖĢņØĖņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. Ēśäņ×¼ ĻĄŁļé┤ņŚÉņä£ļŖö ļäż Ļ░Ćņ¦ĆņØś NOACĻ░Ć ņ▓śļ░® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśļ®░ ļéśņØ┤, ņ▓┤ņżæ ļ░Å ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖźĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņ×äņāü ņÜöņØĖĻ│╝ ļ│ĄņÜ®ļ░®ļ▓ĢņŚÉ ļö░ļźĖ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ņäĀĒśĖļÅä ļō▒ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ņĢīļ¦×ņØĆ NOACļź╝ ņäĀĒāØĒĢśĻ│Ā Ļ░üĻ░üņØś ņÜ®ļ¤ē Ļ░Éļ¤ē ĻĖ░ņżĆņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ļ░Éļ¤ēĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż. ļŗżļźĖ ņĢĮņĀ£ņÖĆņØś ņāüĒśĖņ×æņÜ®ņØ┤ ņÖĆĒīīļ”░ļ│┤ļŗżļŖö ņĀüņ¦Ćļ¦ī ņĪ┤ņ×¼ĒĢśļ»ĆļĪ£ NOACņØś ņ▓śļ░®ņØä ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢĀ ļĢī Ēśäņ×¼ ļ│ĄņÜ®ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņ׳Ļ▒░ļéś ņāłļĪŁĻ▓ī ņČöĻ░ĆļÉ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ĒÖĢņØĖņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢśļŗż. NOACļŖö ņÖĆĒīīļ”░Ļ│╝ ļŗ¼ļ”¼ ņ¦¦ņØĆ ļ░śĻ░ÉĻĖ░ļź╝ Ļ░Ćņ¦Ćļ»ĆļĪ£ ņ▓śļ░®ņØä ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢĀ ļĢī ņĢĮņĀ£ ņł£ņØæļÅäļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņØ┤ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ņØ┤ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒÖśņ×ÉņØś ĻĄÉņ£Ī ļō▒ Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ļ¬©ļōĀ ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØä ņĀüņĀłĒĢśĻ▓ī ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢśĻ▓Āļŗż. ĻĘĖ ņÖĖ ņŗĀĻĖ░ļŖź ļśÉļŖö Ļ░äĻĖ░ļŖź ņןņĢĀĻ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ņé¼ņÜ®ņŚÉ ņ£ĀņØśĒĢśņŚ¼ņĢ╝ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

Acknowledgements

ņ×ÉļŻī ņłśņ¦æņŚÉ ļÅäņøĆņØä ņŻ╝ņŗĀ ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ļ╣äņŚĀņŚÉņŖż ņĀ£ņĢĮ ņ▒äņåĪĒÖö, ļ░öņØ┤ņŚś ņĮöļ”¼ņĢä ņĄ£ņóģņøÉ, ļ│┤ļĀ╣ ņĀ£ņĢĮ ņØ┤ņŖ╣ņŚ░, ĒĢ£ĻĄŁ ļŗżņØ┤ņ░ī ņé░ņ┐ä ļ░ĢņøÉļŗśĻ╗ś Ļ░Éņé¼ļź╝ ļō£ļ”Įļŗłļŗż.

REFERENCES

1. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace 2016;18:1609ŌĆō1678.

2. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739ŌĆō2791.

3. Lip GYH, Collet JP, Caterina R, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease: a joint consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease, Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), South African Heart (SA Heart) Association and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulaci├│n Card├Łaca y Electrofisiolog├Ła (SOLEACE). Europace 2017;19:1757ŌĆō1758.

4. Avezum A, Lopes RD, Schulte PJ, et al. Apixaban in comparison with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: findings From the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial. Circulation 2015;132:624ŌĆō632.

5. Ezekowitz MD, Nagarakanti R, Noack H, et al. Comparison of dabigatran and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: the RE-LY trial (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulant Therapy). Circulation 2016;134:589ŌĆō598.

6. Breithardt G, Baumgartner H, Berkowitz SD, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes with rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation but underlying native mitral and aortic valve disease participating in the ROCKET AF trial. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3377ŌĆō3385.

7. De Caterina R, Renda G, Carnicelli AP, et al. Valvular heart disease patients on edoxaban or warfarin in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1372ŌĆō1382.

8. Pan KL, Singer DE, Ovbiagele B, Wu YL, Ahmed MA, Lee M. Effects of non-vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:pii: e005835.

9. Renda G, Ricci F, Giugliano RP, De Caterina R. Non-vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1363ŌĆō1371.

10. Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Shah ND, Gersh BJ. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2016;209:181ŌĆō183.

11. Barnes GD, Ageno W, Ansell J, Kaatz S. Recommendation on the nomenclature for oral anticoagulants: communication from the SSC of the ISTH: reply. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:2132ŌĆō2133.

12. Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Shah ND, Gersh BJ. Stroke and bleeding risks in NOAC- and warfarin-treated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:3020ŌĆō3021.

13. Dominguez F, Climent V, Zorio E, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2017;248:232ŌĆō238.

14. van Diepen S, Hellkamp AS, Patel MR, et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: insights from ROCKET AF. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:740ŌĆō747.

15. McMurray JJ, Ezekowitz JA, Lewis BS, et al. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, heart failure, and the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:451ŌĆō460.

16. Magnani G, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: insights from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:1153ŌĆō1161.

17. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893ŌĆō2962.

18. Lane DA, Aguinaga L, Blomstr├Čm-Lundqvist C, et al. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias and patient values and preferences for their management: the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and Sociedad Latinoamericana Estimulaci├│n Card├Łaca y Electrofisiolog├Ła (SOLEACE). Europace 2015;17:1747ŌĆō1769.

19. Heidbuchel H, Berti D, Campos M, et al. Implementation of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in daily practice: the need for comprehensive education for professionals and patients. Thromb J 2015;13:22.

20. Lee JM, Joung B, Cha MJ, et al. 2018 KHRS guidelines for stroke prevention therapy in Korean patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Korean J Med 2018;93:87ŌĆō109.

21. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883ŌĆō891.

22. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981ŌĆō992.

23. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139ŌĆō1151.

24. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2093ŌĆō2104.

25. Lee KH, Joung B, Lee SR, et al. 2018 KHRS expert consensus recommendation for oral anticoagulants choice and appropriate doses: specific situation and high risk patients. Korean J Med 2018;93:110ŌĆō132.

26. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018;53:34ŌĆō78.

27. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2017;39:119ŌĆō177.

28. Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, Blandizzi C; SIF-AIGOFIMMG Group; Italian Society of Pharmacology the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists; Italian Federation of General Practitioners. Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseasesŌĆōa position paper addressing benefits and potential harms of acid suppression. BMC Med 2016;14:179.

29. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with reduced risk of warfarin-related serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1105ŌĆō1112; e1110.

30. Di Minno A, Spadarella G, Spadarella E, Tremoli E, Di Minno G. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving oral anticoagulation: current treatment and pharmacological perspectives. Thromb Res 2015;136:1074ŌĆō1081.

31. Chan EW, Lau WC, Leung WK, et al. Prevention of dabigatran-related gastrointestinal bleeding with gastroprotective agents: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 2015;149:586ŌĆō595; e3.

32. Shields A, Lip GY. Choosing the right drug to fit the patient when selecting oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Intern Med 2015;278:1ŌĆō18.

33. Okumura K, Hori M, Tanahashi N, John Camm A. Special considerations for therapeutic choice of nonŌĆōvitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for Japanese patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Clin Cardiol 2017;40:126ŌĆō131.

34. Diener HC, Aisenberg J, Ansell J, et al. Choosing a particular oral anticoagulant and dose for stroke prevention in individual patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: part 2. Eur Heart J 2016;38:860ŌĆō868.

35. Diener HC, Aisenberg J, Ansell J, et al. Choosing a particular oral anticoagulant and dose for stroke prevention in individual patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: part 1. Eur Heart J 2016;38:852ŌĆō859.

36. Lane DA, Barker RV, Lip GY. Best practice for atrial fibrillation patient education. Curr Pharm Des 2015;21:533ŌĆō543.

37. Lane DA, Wood K. Cardiology patient page. Patient guide for taking the non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2015;131:e412ŌĆōe415.

38. Camm AJ, Accetta G, Ambrosio G, et al. Evolving antithrombotic treatment patterns for patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Heart 2017;103:307ŌĆō314.

39. Huisman MV, Rothman KJ, Paquette M, et al. The changing landscape for stroke prevention in AF: findings from the GLORIA-AF Registry Phase 2. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:777ŌĆō785.

40. Steffel J, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients at risk of falling: ENGAGE AFŌĆōTIMI 48 analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1169ŌĆō1178.

41. Romero-Ortuno R, Walsh CD, Lawlor BA, Kenny RA. A frailty instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). BMC Geriatr 2010;10:57.

42. Chao TF, Lip GY, Liu CJ, et al. Relationship of aging and incident comorbidities to stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:122ŌĆō132.

43. Lip GY, Skj├Ėth F, Nielsen PB, Kj├”ldgaard JN, Larsen TB. The HAS-BLED, ATRIA, and ORBIT bleeding scores in atrial fibrillation patients using non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Am J Med 131;574:e513ŌĆō574. e527

44. Guo Y, Zhu H, Chen Y, Lip GY. Comparing bleeding risk assessment focused on modifiable risk factors only versus validated bleeding risk scores in atrial fibrillation. Am J Med 2018;131:185ŌĆō192.

45. Esteve-Pastor MA, Rivera-Caravaca JM, Shantsila A, Rold├Īn V, Lip GY, Mar├Łn F. Assessing bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation patients: comparing a bleeding risk score based only on modifiable bleeding risk factors against the HAS-BLED score. The AMADEUS trial. Thromb Haemost 2017;117:2261ŌĆō2266.

46. Chao TF, Lip GYH, Lin YJ, et al. Major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage risk prediction in patients with atrial fibrillation: attention to modifiable bleeding risk factors or use of a bleeding risk stratification score? A nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol 2018;254:157ŌĆō161.

47. O'Brien EC, Simon DN, Thomas LE, et al. The ORBIT bleeding score: a simple bedside score to assess bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015;36:3258ŌĆō3264.

48. Lip GY, Lane DA. Bleeding risk assessment in atrial fibrillation: observations on the use and misuse of bleeding risk scores. J Thromb Haemost 2016;14:1711ŌĆō1714.

49. Raparelli V, Proietti M, Cangemi R, Lip GY, Lane DA, Basili S. Adherence to oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Focus on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Thromb Haemost 2017;117:209ŌĆō218.

50. Labovitz DL, Shafner L, Reyes Gil M, Virmani D, Hanina A. Using artificial intelligence to reduce the risk of nonadherence in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Stroke 2017;48:1416ŌĆō1419.

51. Beyer-Westendorf J, Ehlken B, Evers T. Real-world persistence and adherence to oral anticoagulation for stroke risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2016;18:1150ŌĆō1157.

52. Shore S, Carey EP, Turakhia MP, et al. Adherence to dabigatran therapy and longitudinal patient outcomes: insights from the veterans health administration. Am Heart J 2014;167:810ŌĆō817.

53. Gorst-Rasmussen A, Skj├Ėth F, Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Lip GY, Lane DA. Dabigatran adherence in atrial fibrillation patients during the first year after diagnosis: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:495ŌĆō504.

54. McHorney CA, Crivera C, Lalibert├® F, et al. Adherence to non-vitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulant medications based on the pharmacy quality alliance measure. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:2167ŌĆō2173.

55. Crivera C, Nelson WW, Bookhart B, et al. Pharmacy quality alliance measure: adherence to non-warfarin oral anticoagulant medications. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:1889ŌĆō1895.

56. Coleman CI, Tangirala M, Evers T. Medication adherence to rivaroxaban and dabigatran for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Int J Cardiol 2016;212:171ŌĆō173.

57. McHorney CA, Peterson ED, Lalibert├® F, et al. Comparison of adherence to rivaroxaban versus apixaban among patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Ther 2016;38:2477ŌĆō2488.

58. Brown JD, Shewale AR, Talbert JC. Adherence to rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban for stroke prevention in incident, treatment-na├»ve nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22:1319ŌĆō1329.

59. Zhou M, Chang HY, Segal JB, Alexander GC, Singh S. Adherence to a novel oral anticoagulant among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21:1054ŌĆō1062.

60. Manzoor BS, Lee TA, Sharp LK, Walton SM, Galanter WL, Nutescu EA. Real-world adherence and persistence with direct oral anticoagulants in adults with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacotherapy 2017;37:1221ŌĆō1230.

61. Cutler TW, Chuang A, Huynh TD, et al. A retrospective descriptive analysis of patient adherence to dabigatran at a large academic medical center. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:1028ŌĆō1034.

62. Graham DJ, Reichman ME, Wernecke M, et al. Cardiovascular, bleeding, and mortality risks in elderly medicare patients treated with dabigatran or warfarin for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2015;131:157ŌĆō164.

63. Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Skj├Ėth F, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate and warfarin in "real-world" patients with atrial fibrillation: a prospective nationwide cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2264ŌĆō2273.

64. Lip GY, Keshishian A, Kamble S, et al. Real-world comparison of major bleeding risk among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients initiated on apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. A propensity score matched analysis. Thromb Haemost 2016;116:975ŌĆō986.

65. Adeboyeje G, Sylwestrzak G, Barron JJ, et al. Major bleeding risk during anticoagulation with warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2017;23:968ŌĆō978.

66. Bai Y, Deng H, Shantsila A, Lip GY. Rivaroxaban versus dabigatran or warfarin in real-world studies of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2017;48:970ŌĆō976.

67. Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Saba S. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin in newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1813ŌĆō1819.

68. Bai Y, Shi XB, Ma CS, Lip GYH. Meta-analysis of effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation with focus on apixaban. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1689ŌĆō1695.

69. Staerk L, Fosb├Ėl EL, Lip GY, et al. Ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke associated with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin use in patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J 2017;38:907ŌĆō915.

70. Beyer-Westendorf J, Camm AJ, Coleman CI, Tamayo S. Rivaroxaban real-world evidence: validating safety and effectiveness in clinical practice. Thromb Haemost 2016;116(Suppl 2):S13ŌĆōS23.

71. Potpara TS, Lip GY. Postapproval observational studies of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2017;317:1115ŌĆō1116.

72. Friberg L, Oldgren J. Efficacy and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Open Heart 2017;4:e000682.

73. Ntaios G, Papavasileiou V, Makaritsis K, Vemmos K, Michel P, Lip GYH. Real-world setting comparison of non-vitamin-k antagonist oral anticoagulants versus vitamin-K antagonists for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2017;48:2494ŌĆō2503.

74. Larsen TB, Skj├Ėth F, Nielsen PB, Kj├”ldgaard JN, Lip GY. Comparative effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2016;353:i3189.

75. Halvorsen S, Ghanima W, Fride Tvete I, et al. A nationwide registry study to compare bleeding rates in patients with atrial fibrillation being prescribed oral anticoagulants. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017;3:28ŌĆō36.

76. Nielsen PB, Skj├Ėth F, S├Ėgaard M, Kj├”ldgaard JN, Lip GY, Larsen TB. Effectiveness and safety of reduced dose non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: propensity weighted nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2017;356:j510.

77. Hohnloser SH, Basic E, Nabauer M. Comparative risk of major bleeding with new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and phenprocoumon in patients with atrial fibrillation: a post-marketing surveillance study. Clin Res Cardiol 2017;106:618ŌĆō628.

78. Lamberts M, Staerk L, Olesen JB, et al. Major bleeding complications and persistence with oral anticoagulation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: contemporary findings in real-life danish patients. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e004517.

79. Coleman CI, Antz M. Real-world evidence with apixaban for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in Germany: a retrospective study (REASSESS). Intern Emerg Med 2017;12:419ŌĆō422.

80. Li XS, Deitelzweig S, Keshishian A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of apixaban versus warfarin in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients in "real-world" clinical practice. A propensity-matched analysis of 76,940 patients. Thromb Haemost 2017;117:1072ŌĆō1082.

81. Deitelzweig S, Farmer C, Luo X, et al. Comparison of major bleeding risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation receiving direct oral anticoagulants in the real-world setting: a network meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin 2018;34:487ŌĆō498.

82. Obamiro KO, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR. A summary of the literature evaluating adherence and persistence with oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2016;16:349ŌĆō363.

83. Martinez C, Katholing A, Wallenhorst C, Freedman SB. Therapy persistence in newly diagnosed non-valvular atrial fibrillation treated with warfarin or NOAC. A cohort study. Thromb Haemost 2016;115:31ŌĆō39.

84. Nelson WW, Song X, Coleman CI, et al. Medication persistence and discontinuation of rivaroxaban versus warfarin among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:2461ŌĆō2469.

85. Lalibert├® F, Cloutier M, Nelson WW, et al. Real-world comparative effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban and warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:1317ŌĆō1325.

86. Zalesak M, Siu K, Francis K, et al. Higher persistence in newly diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients treated with dabigatran versus warfarin. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:567ŌĆō574.

87. Beyer-Westendorf J, F├Črster K, Ebertz F, et al. Drug persistence with rivaroxaban therapy in atrial fibrillation patients-results from the Dresden non-interventional oral anticoagulation registry. Europace 2015;17:530ŌĆō538.

88. Jackevicius CA, Tsadok MA, Essebag V, et al. Early non-persistence with dabigatran and rivaroxaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2017;103:1331ŌĆō1338.

89. Paquette M, Riou Fran├¦a L, Teutsch C, et al. Persistence with dabigatran therapy at 2 years in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1573ŌĆō1583.

90. Desteghe L, Engelhard L, Raymaekers Z, et al. Knowledge gaps in patients with atrial fibrillation revealed by a new validated knowledge questionnaire. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:906ŌĆō914.

91. Vinereanu D, Lopes RD, Bahit MC, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment with oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation (IMPACT-AF): an international, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2017;390:1737ŌĆō1746.

92. Shore S, Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner A, et al. Site-level variation in and practices associated with dabigatran adherence. JAMA 2015;313:1443ŌĆō1450.

93. Guo Y, Chen Y, Lane DA, Liu L, Wang Y, Lip GYH. Mobile health technology for atrial fibrillation management integrating decision support, education, and patient involvement: mAF app trial. Am J Med 2017;130:1388ŌĆō1396; e1386.

94. Bae JP, Dobesh PP, Klepser DG, et al. Adherence and dosing frequency of common medications for cardiovascular patients. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:139ŌĆō146.

95. Weeda ER, Coleman CI, McHorney CA, Crivera C, Schein JR, Sobieraj DM. Impact of once- or twice-daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic cardiovascular disease medications: a meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016;216:104ŌĆō109.

96. Lalibert├® F, Nelson WW, Lefebvre P, Schein JR, Rondeau-Leclaire J, Duh MS. Impact of daily dosing frequency on adherence to chronic medications among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Adv Ther 2012;29:675ŌĆō690.

97. Coleman CI, Roberts MS, Sobieraj DM, Lee S, Alam T, Kaur R. Effect of dosing frequency on chronic cardiovascular disease medication adherence. Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:669ŌĆō680.

98. S├Ėrensen R, Jamie Nielsen B, Langtved Pallisgaard J, Ji-Young Lee C, Torp-Pedersen C. Adherence with oral anticoagulation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a comparison of vitamin K antagonists and non-vitamin K antagonists. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017;3:151ŌĆō156.

99. Forslund T, Wettermark B, Hjemdahl P. Comparison of treatment persistence with different oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:329ŌĆō338.

100. Andrade JG, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, Purdham D, Ciaccia A, Connors S. Values and preferences of physicians and patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who receive oral anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:747ŌĆō753.

101. Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, McBane RD, Shah ND. Direct comparison of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban for effectiveness and safety in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Chest 2016;150:1302ŌĆō1312.

102. Al-Khalili F, Lindstr├Čm C, Benson L. The safety and persistence of non-vitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients treated in a well structured atrial fibrillation clinic. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:779ŌĆō785.

104. Deshpande CG, Kogut S, Willey C. Real-world health care costs based on medication adherence and risk of stroke and bleeding in patients treated with novel anticoagulant therapy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;24:430ŌĆō439.

105. Vrijens B, Heidbuchel H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: considerations on once- vs. twice-daily regimens and their potential impact on medication adherence. Europace 2015;17:514ŌĆō523.

106. Kreutz R, Persson PB, Kubitza D, et al. Dissociation between the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of once-daily rivaroxaban and twice-daily apixaban: a randomized crossover study. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15:2017ŌĆō2028.

107. Desteghe L, Vijgen J, Koopman P, et al. Telemonitoring-based feedback improves adherence to non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants intake in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2018;39:1394ŌĆō1403.

108. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Transition of patients from blinded study drug to open-label anticoagulation: the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:576ŌĆō584.

109. Patel MR, Hellkamp AS, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Outcomes of discontinuing rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: analysis from the ROCKET AF trial (Rivaroxaban Once-Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:651ŌĆō658.

110. Granger CB, Lopes RD, Hanna M, et al. Clinical events after transitioning from apixaban versus warfarin to warfarin at the end of the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial. Am Heart J 2015;169:25ŌĆō30.

111. Gnoth MJ, Buetehorn U, Muenster U, Schwarz T, Sandmann S. In vitro and in vivo P-glycoprotein transport characteristics of rivaroxaban. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2011;338:372ŌĆō380.

112. Mueck W, Kubitza D, Becka M. Co-administration of rivaroxaban with drugs that share its elimination pathways: pharmacokinetic effects in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:455ŌĆō466.

113. Wang L, Zhang D, Raghavan N, et al. In vitro assessment of metabolic drug-drug interaction potential of apixaban through cytochrome P450 phenotyping, inhibition, and induction studies. Drug Metab Dispos 2010;38:448ŌĆō458.

114. LaHaye SA, Gibbens SL, Ball DG, Day AG, Olesen JB, Skanes AC. A clinical decision aid for the selection of antithrombotic therapy for the prevention of stroke due to atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2163ŌĆō2171.

115. Reilly PA, Lehr T, Haertter S, et al. The effect of dabigatran plasma concentrations and patient characteristics on the frequency of ischemic stroke and major bleeding in atrial fibrillation patients: the RE-LY trial (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:321ŌĆō328.

116. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Association between edoxaban dose, concentration, anti-Factor Xa activity, and outcomes: an analysis of data from the randomised, double-blind ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Lancet 2015;385:2288ŌĆō2295.

117. Lip GY, Clemens A, Noack H, Ferreira J, Connolly SJ, Yusuf S. Patient outcomes using the European label for dabigatran. A post-hoc analysis from the RE-LY database. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:933ŌĆō942.

118. Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation 2011;123:2363ŌĆō2372.

119. Hori M, Matsumoto M, Tanahashi N, et al. Rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation - the J-ROCKET AF study. Circ J 2012;76:2104ŌĆō2111.

120. Alexander JH, Andersson U, Lopes RD, et al. Apixaban 5 mg twice daily and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced age, low body weight, or high creatinine: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:673ŌĆō681.

121. Blech S, Ebner T, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Stangier J, Roth W. The metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos 2008;36:386ŌĆō399.

122. Stangier J, St├żhle H, Rathgen K, Fuhr R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the direct oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet 2008;47:47ŌĆō59.

123. Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, Mueck W. Effect of food, an antacid, and the H2 antagonist ranitidine on the absorption of BAY 59-7939 (rivaroxaban), an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2006;46:549ŌĆō558.

124. Mendell J, Tachibana M, Shi M, Kunitada S. Effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2011;51:687ŌĆō694.

125. Upreti VV, Song Y, Wang J, et al. Effect of famotidine on the pharmacokinetics of apixaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol 2013;5:59ŌĆō66.

126. Song Y, Chang M, Suzuki A, et al. Evaluation of crushed tablet for oral administration and the effect of food on apixaban pharmacokinetics in healthy adults. Clin Ther 2016;38:1674ŌĆō1685; e1671.

127. Duchin K, Duggal A, Atiee GJ, et al. An open-label crossover study of the pharmacokinetics of the 60-mg edoxaban tablet crushed and administered either by a nasogastric tube or in apple puree in healthy adults. Clin Pharmacokinet 2018;57:221ŌĆō228.

128. Moore KT, Krook MA, Vaidyanathan S, Sarich TC, Damaraju CV, Fields LE. Rivaroxaban crushed tablet suspension characteristics and relative bioavailability in healthy adults when administered orally or via nasogastric tube. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2014;3:321ŌĆō327.

129. Liesenfeld KH, Lehr T, Dansirikul C, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation from the RE-LY trial. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:2168ŌĆō2175.

130. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, et al. Evaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: design and rationale for the Effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next GEneration in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48). Am Heart J 2010;160:635ŌĆō641.

131. Frost CE, Byon W, Song Y, et al. Effect of ketoconazole and diltiazem on the pharmacokinetics of apixaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79:838ŌĆō846.

132. Salazar DE, Mendell J, Kastrissios H, et al. Modelling and simulation of edoxaban exposure and response relationships in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost 2012;107:925ŌĆō936.

133. Steffel J, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation on amiodarone: a subgroup analysis of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2239ŌĆō2245.

134. Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Heidbuchel H. The significance of drug-drug and drug-food interactions of oral anticoagulation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2018;7:55ŌĆō61.

135. Godier A, Dincq AS, Martin AC, et al. Predictors of pre-procedural concentrations of direct oral anticoagulants: a prospective multicentre study. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2431ŌĆō2439.

136. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after pci in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1513ŌĆō1524.

137. Ruschitzka F, Meier PJ, Turina M, L├╝scher TF, Noll G. Acute heart transplant rejection due to Saint John's wort. Lancet 2000;355:548ŌĆō549.

138. Dans AL, Connolly SJ, Wallentin L, et al. Concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy with dabigatran or warfarin in the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation 2013;127:634ŌĆō640.

139. Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012;366:9ŌĆō19.

140. APPRAISE Steering Committee and Investigators, Alexander JH, Becker RC, et al. Apixaban, an oral, direct, selective factor Xa inhibitor, in combination with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: results of the Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic and Safety Events (APPRAISE) trial. Circulation 2009;119:2877ŌĆō2885.

141. Proietti M, Raparelli V, Olshansky B, Lip GY. Polypharmacy and major adverse events in atrial fibrillation: observations from the AFFIRM trial. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:412ŌĆō420.

142. Piccini JP, Hellkamp AS, Washam JB, et al. Polypharmacy and the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus warfarin in the prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2016;133:352ŌĆō360.

143. Jaspers Focks J, Brouwer MA, Wojdyla DM, et al. Polypharmacy and effects of apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: post hoc analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial. BMJ 2016;353:i2868.

144. Bansal N, Zelnick LR, Alonso A, et al. eGFR and albuminuria in relation to risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of the jackson heart study, the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis, and the cardiovascular health study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1386ŌĆō1398.

145. Go AS, Fang MC, Udaltsova N, et al. Impact of proteinuria and glomerular filtration rate on risk of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Circulation 2009;119:1363ŌĆō1369.

146. Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Go AS, et al. Chronic kidney disease and prevalent atrial fibrillation: the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC). Am Heart J 2010;159:1102ŌĆō1107.

147. Watanabe H, Watanabe T, Sasaki S, Nagai K, Roden DM, Aizawa Y. Close bidirectional relationship between chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation: the Niigata preventive medicine study. Am Heart J 2009;158:629ŌĆō636.

148. Reinecke H, Brand E, Mesters R, et al. Dilemmas in the management of atrial fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:705ŌĆō711.

149. Steffel J, Hindricks G. Apixaban in renal insufficiency: successful navigation between the Scylla and Charybdis. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2766ŌĆō2768.

150. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604ŌĆō612.

151. Lindner SM, Fordyce CB, Hellkamp AS, et al. Treatment consistency across levels of baseline renal function with rivaroxaban or warfarin: A ROCKET AF (Rivaroxaban Once-Daily, Oral, Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) analysis. Circulation 2017;135:1001ŌĆō1003.

152. Fanikos J, Burnett AE, Mahan CE, Dobesh PP. Renal function considerations for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am J Med 2017;130:1015ŌĆō1023.

153. Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, et al. Impact of renal function on outcomes with edoxaban in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Circulation 2016;134:24ŌĆō36.

154. Bonde AN, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Net clinical benefit of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: a nationwide observational cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2471ŌĆō2482.

155. Friberg L, Benson L, Lip GY. Balancing stroke and bleeding risks in patients with atrial fibrillation and renal failure: the Swedish Atrial Fibrillation Cohort study. Eur Heart J 2015;36:297ŌĆō306.

156. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Asinger RW, Herzog CA. Warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients with moderate chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:2599ŌĆō2604.

157. Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:625ŌĆō635.

158. Fox KA, Piccini JP, Wojdyla D, et al. Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2387ŌĆō2394.

159. Hijazi Z, Hohnloser SH, Andersson U, et al. Efficacy and safety of apixaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in relation to renal function over time: insights From the ARISTOTLE Randomized Clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:451ŌĆō460.

160. Hijazi Z, Hohnloser SH, Oldgren J, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin in relation to baseline renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: a RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial analysis. Circulation 2014;129:961ŌĆō970.

161. Hohnloser SH, Hijazi Z, Thomas L, et al. Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2821ŌĆō2830.

162. Yao X, Shah ND, Sangaralingham LR, Gersh BJ, Noseworthy PA. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant dosing in patients with atrial fibrillation and renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:2779ŌĆō2790.

163. Galloway PA, El-Damanawi R, Bardsley V, et al. Vitamin K antagonists predispose to calciphylaxis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephron 2015;129:197ŌĆō201.

164. Hayashi M, Takamatsu I, Kanno Y, et al. A case-control study of calciphylaxis in Japanese end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:1580ŌĆō1584.

165. Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2011;80:572ŌĆō586.

166. Chan KE, Edelman ER, Wenger JB, Thadhani RI, Maddux FW. Dabigatran and rivaroxaban use in atrial fibrillation patients on hemodialysis. Circulation 2015;131:972ŌĆō979.

167. Mavrakanas TA, Samer CF, Nessim SJ, Frisch G, Lipman ML. Apixaban pharmacokinetics at steady state in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:2241ŌĆō2248.

168. Siontis KC, Zhang X, Eckard A, et al. Outcomes associated with apixaban use in end-stage kidney disease patients with atrial fibrillation in the united states. Circulation 2018;138:1519ŌĆō1529.

169. De Vriese AS, Caluw├® R, Bailleul E, et al. Dose-finding study of rivaroxaban in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66:91ŌĆō98.

170. Koretsune Y, Yamashita T, Kimura T, Fukuzawa M, Abe K, Yasaka M. Short-term safety and plasma concentrations of edoxaban in japanese patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and severe renal impairment. Circ J 2015;79:1486ŌĆō1495.

171. Khoury T, Ayman AR, Cohen J, Daher S, Shmuel C, Mizrahi M. The complex role of anticoagulation in cirrhosis: an updated review of where we are and where we are going. Digestion 2016;93:149ŌĆō159.

172. Lauschke VM, Ingelman-Sundberg M. The importance of patient-specific factors for hepatic drug response and toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1714.

173. Efird LM, Mishkin DS, Berlowitz DR, et al. Stratifying the risks of oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:461ŌĆō467.

174. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981ŌĆō992.

175. Kubitza D, Roth A, Becka M, et al. Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a single dose of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;76:89ŌĆō98.

176. Keisu M, Andersson TB. Drug-induced liver injury in humans: the case of ximelagatran. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2010;(196):407ŌĆō418.

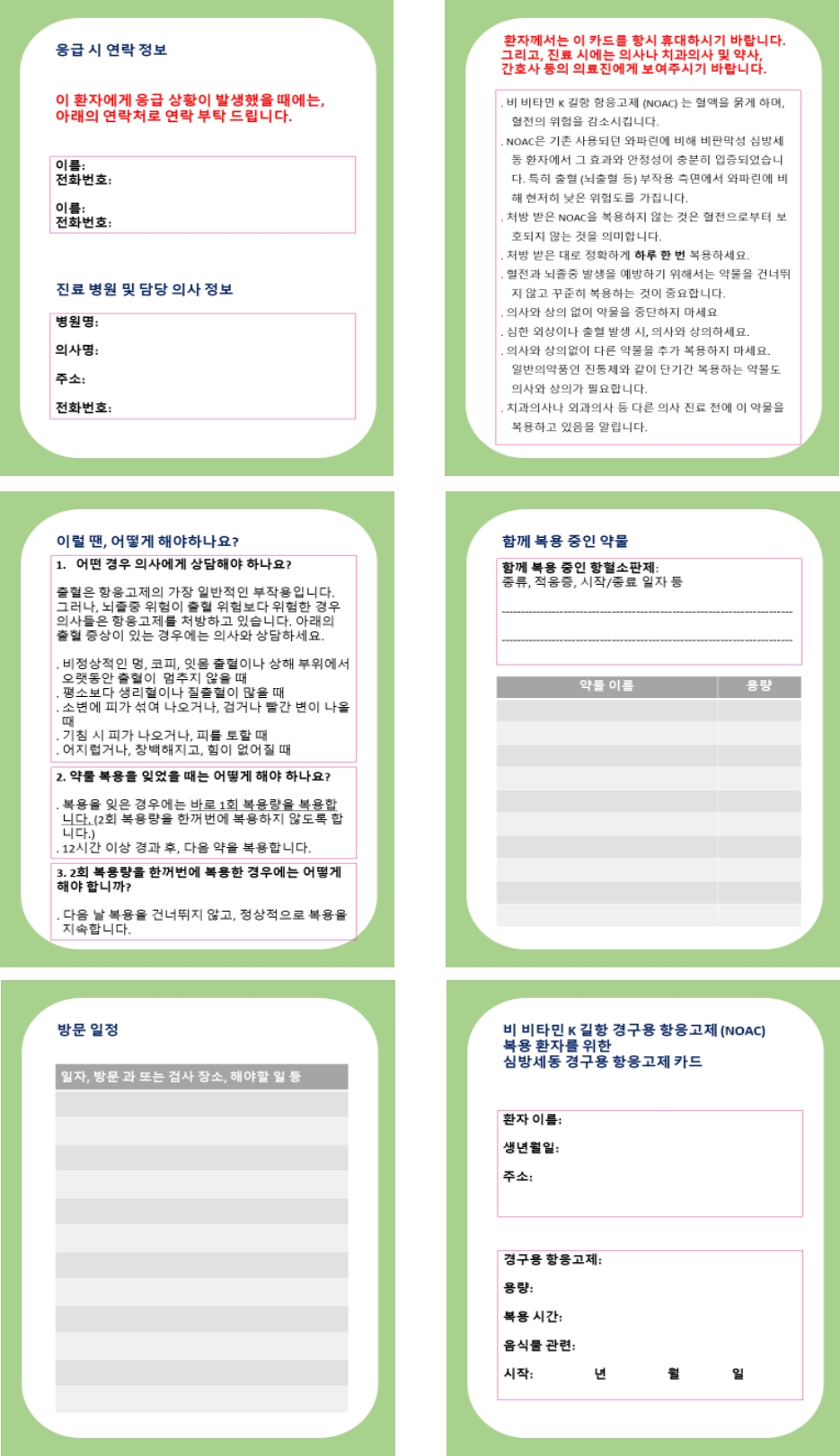

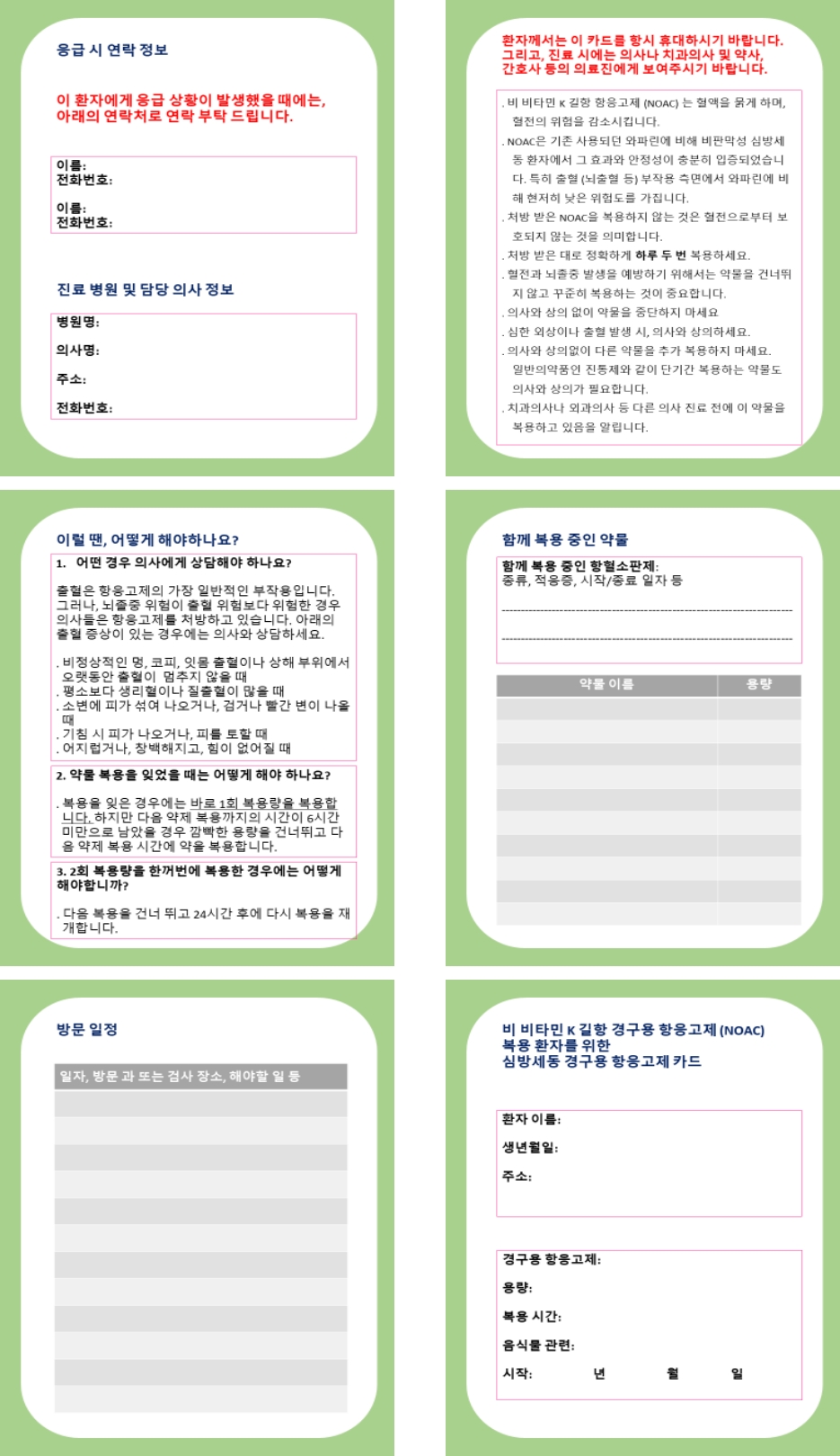

Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) card for patient taking xarelto or lixiana.

Figure┬Ā1.

Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) card for patient taking dabigartran or apixaban.

Figure┬Ā2.

Follow-up for patients treated with NOAC. NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Figure┬Ā3.

Switching from warfarin to NOAC. NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; INR, international normalized ratio.

Figure┬Ā4.

Switching from NOAC to warfarin. NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; INR, international normalized ratio.

Figure┬Ā5.