축성 척추관절염을 가진 한국인 환자의 운동: 설문지 기반 연구

Exercise in Korean Patients with Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Questionnaire-Based Study

Article information

Abstract

목적

운동은 축성 척추관절염 환자의 증상 완화와 강직증 예방을 위하여 널리 권장된다. 그러나 일상생활에서의 운동에 대한 정량적 연구는 부족하다. 본 연구에서는 설문지를 사용하여 이들 환자의 운동 빈도와 지속 시간을 평가하는 것을 목표로 하였다.

방법

2014년 9월부터 2016년 3월까지 류마티스 클리닉을 방문하고 설문 조사에 동의한 축성 척추관절염 환자를 대상으로 조사를 수행하였다. 설문지는 고강도 운동, 중강도 운동, 근력 운동, 걷기 등의 운동 유형을 다루었다. 질병 활성도와 기능적 능력은 각각 배스 강직성 척추염 질환 활동 지수(Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index, BASDAI)와 배스 강직성 척추염 기능 지수(Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index, BASFI)를 사용하여 측정하였다.

결과

조사 대상 환자 645명 중 25.1%가 고강도 운동을, 36.0%가 중강도 운동을, 81.2%가 걷기 운동을, 32.8%가 근력 운동을 하고 있었다. 고강도 운동, 중강도 운동, 걷기 및 근력 운동의 주간 빈도 중앙값은 각각 3.0회(IQR, 2.0-4.0), 3.0회(IQR, 2.0-5.0), 5.5회(IQR, 4.0-7.0), 3.0회(IQR, 2.0-5.0)였다. 고강도 운동, 중강도 운동, 걷기, 근력 운동의 일일 평균 소요 시간은 각각 60분(IQR, 60-120), 60분(IQR, 30-90), 30분(IQR, 20-60), 30분(IQR, 20-60)이었다. 질병 활성도에 따른 운동 비교에서는 BASFI 점수가 BASDAI 점수보다 운동 항목에서 더 많은 차이를 보였다.

결론

축성 척추관절염 환자는 걷기와 같은 저강도 활동을 짧은 시간 동안 선호하는 경향이 있다. 축성 척추관절염 환자에게는 개인별 맞춤 운동 교육이 필요하다.

Trans Abstract

Background/Aims

Exercise is a key component of the management of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), providing symptomatic relief and helping prevent ankylosis. However, there is a lack of quantitative studies evaluating daily exercise patterns in patients with axSpA. This study assessed the types, frequency, and duration of exercises performed by these patients through a structured questionnaire.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included radiographic axSpA patients who visited a rheumatology clinic between September 2014 and March 2016 and provided informed consent to participate. The survey captured information on four types of exercise: high-intensity exercise, moderate-intensity exercise, strength training, and walking. Disease activity and functional status were evaluated using the Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI) and the Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index (BASFI), respectively.

Results

A total of 645 patients participated in the study. Among them, 25.1% engaged in high-intensity exercise, 36.0% in moderate-intensity exercise, 81.2% in walking, and 32.8% in strength training. The median weekly exercise frequency was 3.0 days (interquartile range [IQR], 2.0-4.0) for high-intensity exercise, 3.0 days (IQR, 2.0-5.0) for moderate-intensity exercise, 5.5 days (IQR, 4.0-7.0) for walking, and 3.0 days (IQR, 2.0-5.0) for strength training. The median daily exercise duration was 60 minutes (IQR, 60-120) for high-intensity exercise, 60 minutes (IQR, 30-90) for moderate-intensity exercise, 30 minutes (IQR, 20-60) for walking, and 30 minutes (IQR, 20-60) for strength training. Comparisons by disease activity showed that BASFI scores were more strongly associated with differences in exercise patterns than BASDAI scores.

Conclusion

Radiographic axSpA patients predominantly engaged in low-intensity activities, particularly walking, typically for short durations. Given the observed variations in exercise patterns based on disease activity, personalized exercise education and guidance should be prioritized in clinical practice to optimize axSpA management.

INTRODUCTION

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory condition primarily affecting the spinal and sacroiliac joints, leading to persistent joint pain and a range of extra-musculoskeletal manifestations [1,2]. As the disease progresses, ankylosis of the spine can develop, resulting in significant pain and functional disability, ultimately impairing the quality of life of affected individuals. Consequently, current treatment guidelines for axSpA emphasize the importance of controlling inflammation, alleviating symptoms, and preventing structural damage to optimize patient outcomes.

Management strategies for axSpA include non-pharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches. Non-pharmacological interventions, including patient education, regular exercise, physiotherapy, and smoking cessation, are integral components of axSpA care [2,3]. Among these, regular exercise has been shown to reduce disease activity, alleviate pain, and improve both physical function and spinal mobility in patients with axSpA. However, the therapeutic impact of exercise tends to be modest, and conducting robust clinical trials to evaluate its efficacy presents challenges, particularly due to the inherent difficulty of double-blinding exercise interventions [4]. Despite these limitations, exercise is consistently a key recommendation in various axSpA treatment guidelines [2,3,5,6].

The degree of joint activity and function in axSpA patients can vary considerably, depending on disease severity and the extent of radiographic changes in the spine [7]. Recognizing this variability, the type, frequency, and duration of exercise are likely to differ based on individual patient characteristics and their unique socioeconomic contexts. In Korea, healthcare accessibility and social environment may influence patient behavior, and understanding exercise habits in this population is essential for tailoring clinical recommendations [2].

This study investigated the exercise patterns of Korean patients with radiographic axSpA through a structured survey, aiming to provide practical insights for healthcare professionals to enhance patient management by promoting more individualized and effective exercise regimens in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with radiographic axSpA who visited the rheumatology outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital between September 2015 and December 2015 were recruited to this study. All participants were diagnosed with radiographic axSpA according to the modified New York criteria. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (HYUH 2015-05-016). Given that the study utilized an anonymized survey with minimal risk to participants, formal written consent was not required.

Data collection

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire that included basic epidemiological information, such as age, sex, comorbidities, disease activity status, and the current treatment regimen. Disease activity and functional status were assessed using the Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI) and the Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index (BASFI), respectively.

The survey also included questions about exercise habits, categorized into four types of physical activity: high-intensity exercise, moderate-intensity exercise, walking, and strength training. High-intensity exercise was defined as vigorous activities, such as running or sprinting, which cause a significant increase in heart rate. Moderate-intensity exercise referred to activities such as brisk walking, cycling, or light jogging, which moderately elevate the heart rate. Patients were asked to indicate whether they participated in each type of exercise, and to report their exercise frequency (days per week) and daily duration (minutes per session) for each category.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, and the results were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and were expressed as frequencies and percentages. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Differences in exercise patterns between male and female participants were examined using basic epidemiological data. The frequency of participation in each of the four exercise categories was visualized using histograms. Additionally, to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and disease activity, participants were stratified based on their BASDAI scores (≥ 4 vs. < 4) and BASFI scores (≥ 3 vs. < 3), and comparisons were made for each group [8].

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 3.6.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 645 radiographic axSpA patients completed the survey (Table 1). The median age of the participants was 37.0 years (IQR, 31.0-45.0), with a predominance of males (553 males, 85.7%; 92 females, 14.3%). Among the surveyed patients, 336 (53.1%) were receiving biological agents, and their disease activity levels were generally low, with median BASDAI and BASFI scores of 2.8 (IQR, 1.7-4.4) and 1.1 (IQR, 0.1-2.8), respectively.

Walking was the most commonly reported form of exercise, with 81.2% of the patients participating therein. This was followed by moderate-intensity exercise (36.0%), strength training (32.8%), and high-intensity exercise (25.1%). Walking was also the most frequent exercise type, with a median frequency of 5.5 days per week (IQR, 4.0-7.0). The median duration of daily exercise was 60.0 minutes for both high- and moderate-intensity exercises, with ranges of 60.0-120.0 minutes and 30.0-90.0 minutes, respectively.

Significant sex-based differences were observed in several variables. Males had a higher body mass index and higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and hypertension compared to females. In contrast, females exhibited significantly higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates and BASDAI scores. Regarding exercise patterns, the prevalence of high-intensity exercise and strength training was significantly higher in males than in females (26.8% vs. 15.2%, p= 0.025 and 35.0% vs. 20.2%, p= 0.009, respectively). Furthermore, males reported longer daily durations of high-intensity exercise and more frequent weekly walking compared to females (60.0 minutes [IQR, 60.0-120.0] vs. 50.0 minutes [IQR, 30.0-60.0], p= 0.013 and 6.0 days [IQR, 4.0-7.0] vs. 5.0 days [IQR, 3.0-7.0], p= 0.029, respectively).

Exercise frequency and duration

The types of exercises performed by patients with radiographic axSpA are shown in Fig. 1. Walking was the most commonly reported exercise among both males and females, with 596 participants reporting regular participation.

Distribution of participation in high- and moderate-intensity exercises, strength training, and walking, categorized by sex. The bars represent the number of males and females participating or not participating in each type of exercise. Walking demonstrated the highest participation rate of all exercise types.

The frequency of exercise per week is shown in Fig. 2. For high-intensity exercise, moderate-intensity exercise, and strength training, more than half of the participants reported exercising for 3 days or fewer per week. In contrast, walking had the highest weekly frequency, with many patients reporting daily engagement (7 days per week).

Frequency of exercise per week (in days). The frequency of participation in high-intensity exercise, moderate-intensity exercise, strength training, and walking, stratified by sex, is presented. Walking showed the highest frequency of participation across all exercise types.

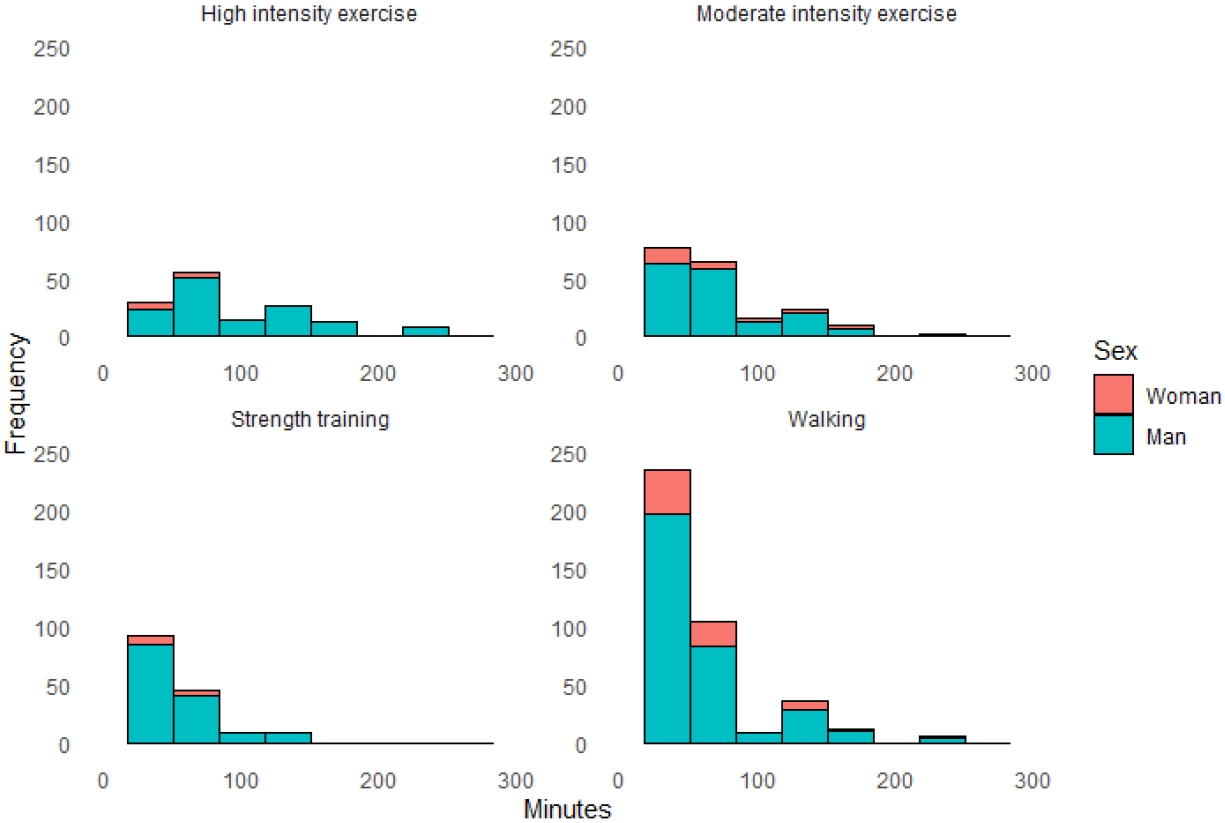

Daily exercise durations are presented in Fig. 3. The majority of participants exercised for < 100 minutes per day across all exercise categories. Walking durations were predominantly < 100 minutes. Males tended to report longer durations of high-intensity exercise and strength training, whereas females exhibited slightly higher participation in moderate-intensity activities.

Distribution of daily exercise duration. Males generally reported longer exercise durations for high-intensity and strength-training exercises. Females showed slightly higher participation in moderate-intensity activities. Walking, despite its high participation rate, was mostly concentrated in shorter daily durations.

Exercise differences according to disease activity

Table 2 presents the differences in exercise frequency and duration based on disease activity levels. Patients with a BASDAI score < 4 were more likely to engage in strength training compared to those with a BASDAI score ≥ 4 (37.1% vs. 26.7%, p= 0.023). Among walking participants, individuals with a BASDAI score ≥ 4 reported longer daily walking durations than those with a BASDAI score < 4 (median, 40.0 minutes [IQR, 20.0-60.0] vs. 30.0 minutes [IQR, 20.0-60.0], p= 0.025).

Moderate-intensity exercise and strength training were more frequently performed by patients with a BASFI score < 3 compared to those with a BASFI score ≥ 3 (40.3% vs. 29.6%, p= 0.041 and 37.1% vs. 23.0%, p= 0.005, respectively). Additionally, patients with a BASFI score < 3 engaged in walking more frequently per week than those with a BASFI score ≥ 3 (median, 6.0 days [IQR, 4.0-7.0] vs. 5.0 days [IQR, 3.0-7.0], p= 0.019). However, the duration of daily walking was longer in patients with a BASFI score ≥ 3 compared to those with a BASFI score < 3 (median, 40.0 minutes [IQR, 20.0-60.0] vs. 30.0 minutes [IQR, 20.0-60.0], p= 0.049).

DISCUSSION

Patients with radiographic axSpA predominantly favored walking, typically at high frequencies but for short durations. This study demonstrated that variations in exercise type and frequency were associated with differences in BASDAI and BASFI scores. To our knowledge, this was the first study in Korea to explore the types and quantities of exercise among patients with radiographic axSpA, emphasizing the need for improved patient education on the role of exercise in disease management.

In a single-blind, randomized controlled pilot study, maintaining high-intensity exercises, such as endurance and strength training, for 12 weeks in active axSpA patients resulted in reduced disease activity and cardiovascular risk [9]. Despite these benefits, the proportion of patients in our study who engaged in strength training or high-intensity exercises was low. While walking is a common low-intensity activity, its ability to improve disease activity in axSpA remains uncertain. Encouraging patients to incorporate strength training or high-intensity exercises into their routines should be a clinical priority.

The enthesis, a key site affected in axSpA, experiences significant mechanical stress, with inflammation and new bone formation contributing to disease pathology [10-12]. During recovery from microdamage, immune cell migration and the secretion of cytokines and prostaglandins may exacerbate the disease. Previous studies have highlighted osteoimmunological interactions triggered by mechanical stress at entheseal sites [10,13]. Accordingly, physical therapy and exercise have been recommended to enhance tendon elasticity, alleviate range of motion limitations, and improve muscle tone, ultimately reducing disability [14-16].

Exercise plays an important role in axSpA management. Meta-analyses of physical activity have demonstrated that exercise and physical therapy interventions are effective components of disease management [4,17,18]. However, excessive mechanical stress can worsen the condition. This paradox - balancing the benefits and harms of physical activity - has introduced the concept of the Goldilocks zone in axSpA [15]. Due to genetic and immunological factors, the Goldilocks zone for axSpA may be narrower than that of healthy individuals, increasing the risk of adhesions, tendon damage, and bone injury. Thus, exercise regimens must be carefully tailored to each patient’s disease condition [16].

Our findings suggested that disease activity influences specific exercise types and durations. Patients with lower BASDAI and BASFI scores were more likely to engage in strength training, whereas those with higher scores tended to spend more time walking daily. Patients with elevated disease activity appeared to favor simpler exercises. Furthermore, BASFI scores showed a stronger association with exercise patterns than BASDAI scores, suggesting that functional limitations play a significant role in shaping exercise habits. Given the influence of disease activity on exercise preferences, future research should focus on determining the optimal types and amounts of exercise for individual patients. Studies are also needed to establish effective exercise programs tailored to patients’ capabilities and disease stages.

This study had several limitations. First, the survey data were collected some time ago, potentially limiting its relevance to current exercise trends. Second, the diverse lifestyles of patients posed challenges in formulating generalized exercise recommendations. Third, the subjective nature and difficulty of quantifying exercise intensity complicated the accurate assessment of exercise habits. Fourth, the survey included numerous missing items, limiting the comprehensive evaluation of different exercise modalities. Lastly, as the study was conducted at a single tertiary hospital, the cohort likely consisted of patients with more advanced disease stages, which may not be representative of the broader axSpA population.

In conclusion, Korean patients with radiographic axSpA predominantly engage in low-intensity activities, such as walking, often for short durations. This study highlighted the need to design personalized, active exercise programs that align with the needs and functional capabilities of axSpA patients. spondyloarthritis.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

BSK has been an editorial board member since May 2022, but has no role in the decision to publish this article.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2021R1C1C1009815).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

THK had full access to all of the data used in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data, study supervision, and accuracy of its analysis.

Concept and design: THK.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: BSK, JHS.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

Statistical analysis: BSK.

Obtained funding: BSK.

Administrative, technical, or material support: JHS, THK.

Supervision: THK.

Acknowledgements

None.