위식도 역류 질환의 진단과 치료에 관한 서울 진료지침 2020

2020 Seoul Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Article information

Abstract

위식도 역류 질환은 위내용물의 역류로 인하여 불편한 증상이 발생하거나 합병증이 동반되는 질병으로 임상 양상과 검사 소견 및 치료 반응성 측면에서 다양한 임상 양상을 포괄하는 것으로 받아들여지고 있다 최근 리옹 합의에서 객관적인 검사를 통하여 위식도 역류 질환이 확인된 ‘입증된 위식도 역류 질환’이라는 개념을 강조하였고, 그 진단 기준이 강화되었다. 이러한 변화에 맞추어 한국을 비롯한 아시아권에서도 위식도 역류 질환의 진단과 치료에 대한 새로운 전문가들의 합의가 필요하여 위식도 역류 질환 진단 및 치료에 관한 근거를 체계적인 검토 및 메타분석 접근 방식을 사용하여 ‘위식도 역류 질환의 진단과 치료에 관한 서울 진료지침 2020’을 개발하였다. 본 임상진료지침에서는 위식도 역류 질환과 관련된 다양한 정의와 함께 아시아인을 대상으로 한 논문의 메타분석을 통해 식도산노출시간에 대한 참조 범위 상한은 3.2%로 정하였으며, 원위부 식도의 기저 임피던스 값과 역류 후 삼킴유발 연동파 지수 등의 임피던스 검사 지표가 진단에 도움이 될 수 있음을 제시하였다. 또한 양성자펌프억제제와 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제 그리고 기타 약물과 함께 내시경적인 치료 및 항역류수술을 위식도 역류 질환 치료의 전략으로 제시하였다.

Trans Abstract

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which gastric contents regurgitate into the esophagus or beyond, resulting in either troublesome symptoms or complications. GERD is heterogeneous in terms of varied manifestations, test findings, and treatment responsiveness. GERD diagnosis can be established with symptomatology, pathology, or physiology. Recently the Lyon consensus defined the “proven GERD” with concrete evidence for reflux, including advanced grade erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles classification grades C and or D esophagitis), long-segment Barrett’s mucosa or peptic strictures on endoscopy or distal esophageal acid exposure time > 6% on 24-hour ambulatory pH-impedance monitoring. However, some Asian researchers have different opinions on whether the same standards should be applied to the Asian population. The prevalence of GERD is increasing in Asia. The present evidence-based guidelines were developed using a systematic review and meta-analysis approach. In GERD with typical symptoms, a proton pump inhibitor test can be recommended as a sensitive, cost-effective, and practical test for GERD diagnosis. Based on a meta-analysis of 19 estimated acid-exposure time values in Asians, the reference range upper limit for esophageal acid exposure time was 3.2% (95% confidence interval 2.7-3.9%) in the Asian countries. Esophageal manometry and novel impedance measurements, including mucosal impedance and a post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave, are promising in discrimination of GERD among different reflux phenotypes, thus increasing its diagnostic yield. We also propose a long-term strategy of evidence-based GERD treatment with proton pump inhibitors and other drugs.

서 론

위식도 역류 질환(gastroesophageal reflux disease)은 위내용물의 역류로 인하여 불편한 증상이 발생하거나 합병증이 동반되는 질병이다[1]. 최소 주 1회 증상이 있는 경우를 위식도 역류 질환으로 정의한 인구 기반 연구에서의 유병률은 대략 13% 정도로 흔한 질환이다[2]. 이전에는 위식도 역류 질환을 비미란성 역류 질환(non-erosive reflux disease), 미란성 역류 질환, 바렛식도와 같은 하부 질환의 스펙트럼의 질병 모델로 추정하기도 하였다[3]. 이 개념은 비미란성 역류 질환이 진행하여 미란성 역류 질환이 발생하고 식도상피의 화생인 바렛식도를 거쳐 식도 선암까지 진행한다는 가설이다. 그러나 최근 위식도 역류 질환은 위식도 접합부의 기능 저하, 하부 식도 괄약근압 저하, 식도열공탈장, 누운 자세에서 발생하는 역류, 식도산청소능 저하 등과 같은 여러 병인에 의해 유발되며 다양한 임상 양상을 포괄하는 정의로 받아들여지고 있다[4]. 또한 로마기준 IV에 의하면 식도산도검사에 따라 비미란성 역류 질환을 병적 위산 역류로 인한 ‘진성 비미란성 역류 질환(true non-erosive reflux esophagitis)’과 병적인 기준에 합당하지 않지만 역류와 증상이 연관이 있는 ‘역류 과민성(reflux hypersensitivity)’, 위식도 역류와는 무관한 ‘기능성 가슴쓰림(functional heartburn)’으로 분류하고 있다[5]. 이러한 다양한 표현형이 나타나는 이유는 위식도 역류 증상이 내시경이나 식도산도검사 결과와 일치하지 않고, 검사에서 역류의 근거가 없어도 식도과민성이나 인지 과잉(cognitive hypervigilance)이 있는 경우 역류 증상이 나타날 수 있기 때문이다. 위식도 역류 질환의 이러한 임상 표현형이 중요한 것은 그 발병 기전에 따라 다른 치료 접근이 필요하기 때문이다. 위식도 역류 질환이 만성적이고 재발이 흔하여 장기간 산분비억제제를 사용하게 되는데, 이로 인한 사회경제적 부담이 클 뿐 아니라 약제 사용과 연관된 부작용이 일부 보고되고 있으며, 불필요한 항역류 수술이 시행되는 경우가 있어 위식도 역류 질환의 임상 표현형을 이해하고 적절한 치료를 하는 것이 중요하다. 최근 리옹 합의(the Lyon consensus)에서는 객관적인 검사를 통하여 위식도 역류 질환이 확인된 ‘입증된 위식도 역류 질환(proven gastroesophageal reflux disease)’이라는 개념을 강조하였고, 그 진단 기준을 강화하였다[6]. 위식도 역류 질환의 임상 표현형에 따라 맞춤형 치료 방법의 선택은 불필요한 치료를 최소화하고 제한된 의료 자원을 효과적으로 사용할 수 있게 할 것이다. 이러한 변화에 맞추어 한국을 비롯한 아시아권에서도 위식도 역류 질환의 진단과 치료에 대한 새로운 전문가들의 합의가 필요하여 2020년 서울 합의 도출을 통하여 아시아에서 위식도 역류 질환 진단 및 치료에 관한 근거를 기반으로 한 임상진료지침을 개발하였다[7].

방 법

본 임상진료지침은 위식도 역류 질환을 가진 성인 환자를 대상으로 과학적인 근거와 전문가 합의를 거쳐 작성되었다. 본 임상진료지침은 위식도 역류 질환을 진단하고 치료하는 소화기내과 의사, 외과 의사 및 기타 일반 의사 및 간호사, 기사, 의과대학 학생, 의료 보조 인력 등 다양한 의료 관련 종사자, 환자 및 일반인 등이 사용할 수 있는 내용을 포함하였다.

본 지침의 운영위원회는 대한소화기기능성질환·운동학회(Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, KSNM)와 아시아소화관운동학회(Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association, ANMA)의 이사장과 임원으로 구성하였다. 본 지침은 한국보건의료연구원에서 시행하는 환자 중심 의료기술 최적화 연구(Grant No. HI19C0481 and HC19C0060) 와 KSNM에서 재정적 지원을 받아 개발되었으나, 지침 내용에 어떠한 영향 없이 독립적으로 개발되었다. 본 임상진료지침은 근거중심의학 방법에 기초하여 신규 직접 개발 방법(de novo method)으로 개발되었다[7].

본 지침은 2019년 5월 개발을 시작하였고, 개발 기간 동안 4회의 워크숍과 11회의 미팅이 진행되었다. 실무개발팀은 KSNM의 임상진료지침 위원회와 ANMA에서 추천 받은 임원 및 위식도 역류 질환 전문가로 구성하였다. 지침은 1) 정의와 역학, 2) 진단, 3) 치료의 소주제에 맞추어 patient, intervention, comparatives, outcomes (PICO)를 구성하였다. 지침 개발에 참여한 실무 위원은 이해상충에 대하여 사전에 작성된 문서로 제출함으로써 서약하였고, 모든 위원이 이해상충에 대한 영향이 없었음을 확인하였다. 이는 영문판 부록에 명시되어 있다[7].

환자의 선호도를 조사하기 위하여 위식도 역류 질환 관련 인터넷 커뮤니티 회원을 대상으로 2019년 8월 위식도 역류 질환과 연관된 8개의 설문조사에 총 210명이 응답하여 설문 조사를 시행하였다. 이 중 여성이 64.4%, 미란성 역류 질환 68.3%, 비미란성 역류 질환 14.6%였고, 57.6%가 장기간 유지 요법을 하고 있다고 응답하였다. 유지 요법 중 선호하는 치료 방법에 대한 설문에 대하여 76.1%가 필요할 때만 약을 복용하는 방법을 선호한다고 응답하였다. 또한 그 이유에 대한 설문에서 약제 부작용에 대한 우려가 66.3%로 가장 높았다. 이 자료에 기반하여 장기 유지 요법에서 필요 시 요법의 효과와 장기 약제 사용으로 인한 부작용에 대한 핵심 질문을 추가하였다.

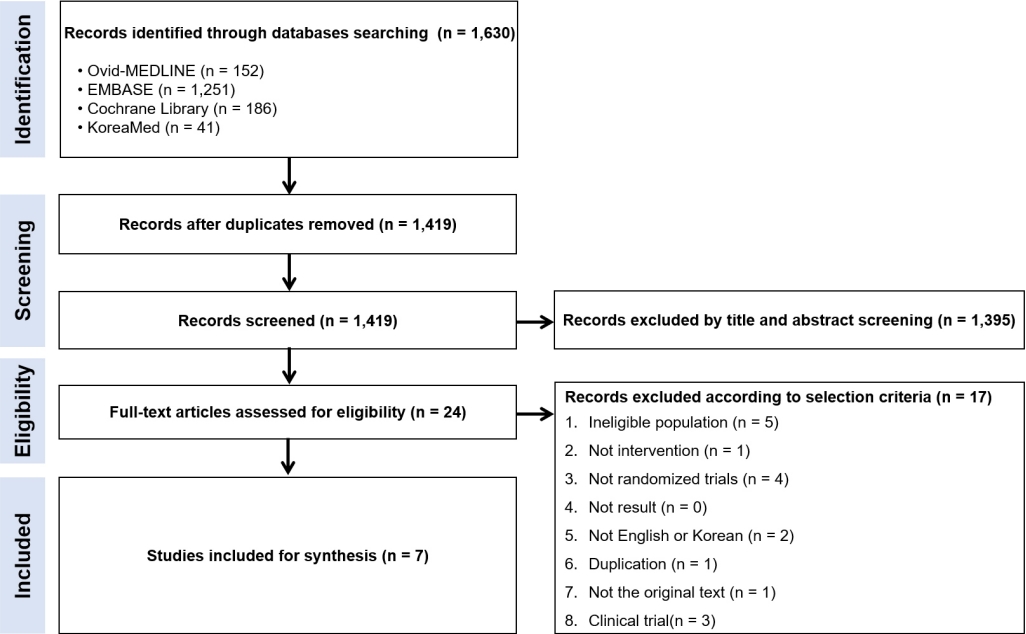

PICO는 명목집단기법으로 실무위원회에서 선정하였고, 각 PICO에 대하여 체계적 문헌 검색과 가능한 경우 메타분석을 시행하였다. 구체적인 방법론은 영문판에 명시하였고, 영문판 부록에 각 핵심 질문에 대한 핵심 단어와 검색 전략, 질 평가 결과 등을 정리하였다[7]. 두 명의 독립적인 위원이 선정된 문헌을 대상으로 각각의 선정, 제외 기준에 따라 문헌을 선정하였다(Fig. 1). 공통적인 선정기준은 1) 성인을 대상으로 한 연구, 2) 영어나 한국어로 작성된 연구, 3) 체계적 문헌고찰, 메타분석, 무작위 배정 연구 및 비무작위 연구, 4) 2000년부터 2019년 사이 진행된 관찰 연구, 5) 확실한 결과가 보고된 연구이다. 공통적인 제외 기준은 1) 유아나 청소년을 대상으로 한 연구, 2) 임상 결과가 확실히 보고되지 않은 연구, 3) 원본을 확인할 수 없는 연구, 4) 증례 보고나 전문가 의견, 지침, 근거 중심인 아닌 종설 등이었다. 메타분석을 바탕으로 grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) 방법으로 근거를 도출하였다(Table 1) [8]. GRADEpro software를 이용하여 높음, 중등도, 낮음, 매우 낮음의 4단계로 근거의 질을 평가하였고, 이를 바탕으로 권고의 강도를 결정하였다[9].

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the systematic review process of the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in patients with non-cardiac chest pain.

델파이 방식으로 전문가 합의를 진행하였다. 참여한 전문가는 KSNM과 ANMA의 참여자 및 기타 전문가로 구성하였다. 1차 평가는 위식도 역류 질환의 정의와 역학에 대한 7개의 권고안, 진단에 대한 8개의 권고안, 치료에 대한 10개의 권고안 총 25개의 권고안과 1개의 개방형 질문으로 구성된 설문을 개발한 근거와 함께 이메일을 통하여 진행하였다. 각 권고안에 대한 동의를 5단계의 리커트 척도 중 4 이상인 경우를 동의로 정의하였고, 모든 대상자의 80% 이상인 경우를 합의로 간주하였다. 1차 이메일 투표에서 양성자펌프억제제 장기 사용의 부작용, 바렛식도에서 약물 치료, 위장관운동촉 진제 및 항역류 수술에 대한 4개의 권고안이 부결되었다. 1차 투표 후 수정된 권고안과 근거에 대하여 2020년 10월 15일 ANMA 학술모임에서 발표하였고, 2차 이메일 투표를 시행하였다. 항역류 수술에 관한 수정 권고안은 통과하였으나 다른 3개의 수정 권고안은 2차 투표에서도 부결되어, 최종 확정된 권고안을 표 2에 정리하였다.

최종 작성된 지침에 대하여 세명의 전문가(Sanjiv Mahadeva [Malaysia], Myung-Gyu Choi [South Korea], Shobna Bhatia [India])가 외부 검토를 시행하여, 진료 지침을 실행하는 데 있어, 특히 생리 검사를 시행하는 데 있어 개원가 등 일차 진료에서 시행할 수 없는 제한점에 대한 극복 방법, 이득과 위해에 대한 기술, 권고안을 적용할 때 비용 효과에 대한 논의를 추가할 것을 권고 받았다.

본 임상진료지침은 영문으로 Journal of Neurogastroenterology & Motility에 게재되었고[7], KSNM 홈페이지(https://www.ksgm.org) 및 대한내과학회 홈페이지(https://www.kaim.or.kr)에서 확인이 가능하여 접근성을 높이고자 하였다. 본 임상진료지침은 새로운 과학적 근거가 축적되면 3-5년마다 갱신할 예정이다.

위식도 역류 질환의 정의와 역학

정의

위식도 역류 질환의 정의

권고안 1. 위식도 역류 질환은 위 내용물이 식도나 구강으로 역류하여 불편한 증상이나 합병증을 유발하는 질환이다.

근거 수준 및 권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(91.1%), 대체로 동의함(8.9%), 미정(0.0%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

위식도 역류 질환의 정의는 2006년 몬트리올 합의의 정의를 채택하였다[1]. 일반적으로 경도의 증상들이 일주일에 2일이상 발생하거나 중등도 이상의 증상들이 일주일에 하루 이상 발생하는 경우, 불편한 증상으로 간주한다. 역류 증상이 있지만 환자가 별로 불편하게 느끼지 않는 경우는 위식도 역류 질환으로 진단되지 않는다.

비미란성 역휴 질환의 정의

권고안 2. 비미란성 역류 질환은 내시경 검사에서 식도 점막 손상이 관찰되지 않지만, 24시간 보행성 식도 산도-임피던스 검사에서 비정상적으로 증가된 위식도 역류를 보이면서 불편한 역류 증상이 있는 경우로 정의 한다.

근거 수준 및 권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(75.6%), 대체로 동의함(22.2%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

전형적인 역류 증상이 있는 환자의 약 70%에서는 내시경 검사에서 미란성 식도염을 보이지 않는다[10,11]. 내시경 검사에서 식도점막 손상이 관찰되지 않지만, 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사에서 비정상적으로 증가된 위식도 역류를 보이면 비미란성 역류 질환으로 간주할 수 있는데, 역류 증상들이 위산 역류와 연관성을 보이는 경우나 위산분비 억제제 투여에 증상의 호전을 보이는 경우에는 더욱 가능성이 높다.

역류 과민성의 정의

권고안 3. 역류 과민성은 병적으로 증가된 위식도 역류는 없으나 생리적 역류로 인해 가슴쓰림이나 흉통이 발생하는 경우로 정의한다.

근거 수준 및 권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(62.2%), 대체로 동의함(35.6%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

역류 과민성은 로마기준 IV에서 처음으로 도입된 개념으로 생리적인 역류에 의하여 유발되는 가슴쓰림이나 흉통과 같은 증상이 있는 경우로 정의한다[5]. 위산분비억제제에 대한 반응 여부와는 상관이 없으며, 비슷한 증상을 유발할 수있는 식도의 구조적 이상, 호산구 식도염 및 주요 식도 운동 장애가 없으면서 증상은 최소한 6개월 이전에 시작되었고, 지난 3개월 동안 일주일에 2회 이상 발생해야 한다[6]. 최근 연구에서 역류 과민성은 식도 점막의 장벽 기능 및 화학적 청소능의 변화, 현미경적 식도염, 명백한 증상-역류 연관성을 고려하여 위식도 역류 질환의 스펙트럼으로 간주해야 한다는 주장이 제기되고 있다[12].

기능성 가슴쓰림의 정의

권고안 4. 기능성 가슴쓰림은 흉골 뒤쪽으로 타는 듯한 불편감이나 통증이 있으나 위식도 역류 질환이 없고 위산분비억제제에도 증상이 완화되지 않는 경우로 정의한다.

근거 수준 및 권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(46.7%), 대체로 동의함(37.8%), 미정(13.3%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(2.2%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

기능성 가슴쓰림은 식도산도검사 혹은 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사에서 위식도 역류 질환에 합당한 소견이 없고, 위산분비억제제에도 증상이 완화되지 않는 흉골 뒤쪽의 타는 듯한 불편감이나 통증으로 정의된다. 가슴쓰림을 유발할 수 있는 주요 식도 운동 장애 혹은 식도의 구조적 이상 및 호산구 식도염이 없어야 하며, 증상은 최소한 6개월 이전에 시작되었고, 지난 3개월 동안 일주일에 2회 이상 발생해야 한다.

불응성 위식도 역류 질환의 정의

권고안 5. 표준 용량의 위산분비억제제를 8주 이상 투여하였음에도 증상이 지속되는 경우를 불응성 위식도 역류 질환으로 정의한다.

근거 수준: 낮음

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(37.8%), 대체로 동의함(57.8%), 미정(4.4%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

아직까지 불응성 위식도 역류 질환(refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease)을 진단하기 위한 위산분비억제제의 투여 용량과 투약 기간, 증상 호전 정도를 평가하는 방법 등과 관련해 합의된 기준은 없는 실정이다. 이전 연구에서는 대개 양성자펌프억제제 표준 용량 또는 표준 용량의 두 배를 복용하였음에도 반응이 없거나 부족한 경우를 불응성으로 정의하며, 치료 반응을 평가하기 위한 기간은 4주에서 12주까지 다양하게 설정하였다[13-15]. 아시아에서는 표준 용량의 위산분비억제제를 8주 이상 투약하였음에도 증상이 전혀 호전되지 않거나 일부만 호전된 경우를 불응성으로 정의하였다[16].

불응성 위식도 역류 질환의 빈도는 정의와 연구 대상 집단의 특성에 따라 차이가 있으나 약 40%로 보고된다[17-20]. 불응성 위식도 역류 질환은 미란성 역류 질환보다는 비미란성 역류 질환에서 더 흔하게 발생하며[21-23], 국내 연구에서 8주간의 양성자펌프억제제 치료에 반응하지 않는 환자의 비율은 비미란성 역류 질환의 19.5%, 미란성 역류 질환의 10.2% 였다[24].

위식도 역류 질환의 식도 외 증상

권고안 6. 위식도 역류 질환은 기침, 천식, 쉰 목소리 또는 비심인성 흉통과 같은 다양한 식도 외 증상을 유발할 수 있다. 위식도 역류 질환의 식도 외 증상은 전형적인 증상을 동반하거나 동반하지 않을 수 있다.

근거 수준 및 권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(62.2%), 대체로 동의함(35.6%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

위식도 역류 질환은 식도 외 증상을 유발할 수 있으며 만성 기침, 쉰 목소리, 천식, 목 이물감, 수면 장애, 치아 미란 및 비심인성 흉통 등이 있다[21,25]. 위식도 역류 질환에 의한 만성 기침은 위 내용물의 기도 흡인에 의한 직접적인 자극과 위식도 역류에 의해 하부 식도의 미주신경이 자극되어 기관지 경련이 유발되는 간접적인 자극에 의해 모두 가능하다[26]. 인후두 역류는 성대와 주변 조직에 영향을 주어 쉰 목소리와 목 이물감 등의 증상을 유발한다[27]. 그 외에 비심인성 흉통은 심장기능이 정상인 환자에서 반복적으로 발생하는 흉골 후방의 협심증 유사 통증으로, 정상 관상동맥 조영술과 내시경 소견을 보이는 904명의 비심인성 흉통 환자를 대상으로 조사한 결과 48.2%에서 위식도 역류 질환이 확인되었다[28]. 식도 외 증상의 유병률은 연구 대상과 증상의 정의에 따라 다양하게 보고되는데, 국내에서 시행된 연구에서는 식도 외 증상의 유병률은 74.4%였으며, 목 이물감 및 비심인성 흉통 그리고 만성 기침 등이 가장 흔한 증상으로 확인되었다[29].

역학

권고안 7. 위식도 역류 질환의 유병률은 아시아 국가에서 증가하고 있다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 강도: 적용불가

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(68.9%), 대체로 동의함(31.1%), 미정(0.0%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

아시아 여러 역학 연구에서 위식도 역류 질환의 유병률은 뚜렷한 증가 추세를 보이고 있다[30]. 아시아 국가에서 시행된 연구를 메타분석 하였을 때(Supplementary Fig. 1), 위식도 역류 질환의 유병률은 2000-2009년 11.0%, 2010-2019년 15.0%로 유의하게 증가하였다(Supplementary Fig. 2). 건강검진을 받은 수검자를 대상으로 한 관찰 연구만을 보았을 때위식도 역류 질환의 유병률은 2000-2009년 6.0%, 2010-2019년 15.0%로 유의하게 증가하였다(Supplementary Fig. 3).

위식도 역류 질환의 진단

진단 설문지

권고안 8. 위식도 역류 질환에서 진단 설문지는 위식도 역류 질환을 진단하는 데 유용하다.

근거 수준: 낮음

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(20.0%), 대체로 동의함(66.7%), 미정(8.9%), 동의하지 않음 (4.4%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

정형화된 진단 설문지는 위식도 역류 질환의 진단 정확도를 높여서 위산분비억제제의 투여가 적합한 대상자를 구분하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다. 위식도 역류 질환의 진단 목적으로 유용성이 검증되고 여러 언어로 번역된 진단 설문지인 GerdQ와 Reflux Disease Questionnaire가 가장 보편적으로 사용되어 왔다[31-33]. 특히 GerdQ 점수가 8점 이상인 환자들의 내시경, 보행성 식도산도검사 및 양성자펌프억제제 투약 반응 정도를 종합한 진단 검사법으로 80%에 달하는 진단 정확도를 보인다.

양성자펌프억제제 검사

권고안 9. 전형적인 위식도 역류 질환 증상이 있는 환자에서 진단을 위해 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제제를 2주간 사용하는 검사는 위식도 역류 질환 진단에 민감하고 실용적인 방법이다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(35.6%), 대체로 동의함(60.7%), 미정(4.4%), 동의하지 않음(0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

가슴쓰림이나 신물이 올라오는 증상은 위식도 역류 질환의 전형적인 증상으로, 위식도 역류 질환을 진단하는 데 민감도 62%, 특이도 67%로 보고되고 있다. 17개 연구 결과를 메타분석 하였을 때(Supplementary Fig. 4), 양성자펌프억제제 검사의 민감도는 78% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.71-0.84), 특이도 40% (95% CI 0.31-0.48)였다(Supplementary Fig. 5). 그러나 양성 자펌프억제제의 용량(표준 용량 대 고용량)과 투여 기간(2주이내 대 2주 이상)에 따른 검사의 민감도와 특이도의 차이는 없었다(Supplementary Fig. 6). 양성자펌프억제제 검사는 비전 형적인 증상을 갖는 경우에는 반응률이 떨어지지만[34,35], 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사 장비가 없는 경우에 비용 효율적으로 쉽게 시도해 볼 수 있다는 점에서 전형적인 위식도 역류 질환이 있는 환자에서 가치가 있다고 할 수 있다.

상부위장관 내시경

권고안 10. 위식도 역류 질환을 진단하고 다른 기질적 질병을 배제하기 위해 상부위장관 내시경 및 조직 생검을 권고할 수 있다.

근거 수준: 매우 낮음

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 합의: 전적으로 동의함(53.3%), 대체로 동의함(42.2%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(2.2%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

상부위장관 내시경은 증상이 있는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 식도 점막 손상을 평가하는 데 오랫동안 사용되어 왔다. 그러나 증상의 강도와 점막 손상의 내시경적 소견의 상관관계가 높지 않아서 예측과 다른 경우도 많다. 실제 내시경 소견에서 Los Angeles (LA) classification A의 점막 손상을 보이는 환자의 1/3에서만 위식도 역류 증상을 보인다는 연구도 있다[10]. 리옹 합의에서는 내시경 소견에서 LA classification C 또는 D 수준의 미란성 역류 질환, 바렛식도 또는 소화성 협착이 보일 경우 위식도 역류 질환의 확증적 증거로 간주하고, LA classification A 또는 B의 경우는 확증적이지 않지만 경계적 소견으로 평가하였다[6]. 위식도 역류 질환의 진단을 위한 생검의 시행은 일반적으로 권장되지 않는다. 내시경 검사 시 조직생검은 소화성 협착, 식도의 악성 종양, 바렛식도 및 호산구성 식도염과 같은 기질적 질환을 감별하고 진단하는 데 사용할 수 있다.

바렛식도에 대한 상부위장관 내시경 추적 검사

권고안 11. 장분절 바렛식도는 상부위장관 내시경 추적 검사를 시행한다.

근거 수준: 매우 낮음

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(40.0%), 대체로 동의함(48.9%), 미정(6.7%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(4.4%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

바렛식도 환자에서 내시경 추적 검사를 시행하는 주된 목적은 바렛식도암으로 인한 사망을 줄이기 위함이다. 최근 발표된 메타분석 결과에 따르면, 내시경 추적 검사를 시행 받지 않은 바렛식도 환자에 비해 추적 검사를 받은 환자에서 식도 선암 사망 위험이 40% 낮았으며, 전체 사망 위험은 25% 낮았다[36-40]. 이러한 이득은 내시경 추적 검사를 통하여 식도암을 조기에 진단하여 치료할 수 있기 때문인데, 바렛식도 환자에서 내시경 추적 검사를 시행할 경우 식도암의 조기 진단율은 2.11배 증가한다[36]. 반대로, 내시경 추적 검사를 시행하는 경우에 비해 내시경 추적 검사를 시행하지 않을 경우 수술적 치료가 필요할 가능성이 47% 증가한다.

그러나 모든 바렛식도 환자에게 내시경 추적 검사를 권유해야만 하는가에 대해서는 아직 논란이 있다. 2016년에 발표된 위식도 역류 질환 치료에 대한 아시아-태평양 컨센서스에서는 이형성증이 동반되어 있지 않은 바렛식도에서 내시경 추적 검사의 이득은 입증되지 않았다고 밝히고 있다[16]. 그러나 최근 발표된 바렛식도의 진행에 관한 메타분석에서 단분절 바렛식도의 식도 선암 이행률은 연간 0.06%였던 것에 비해, 장분절 바렛식도의 식도 선암 이행률은 연간 0.31%로, 장분절 바렛식도의 식도 선암 이행률이 단분절 바렛식도보다 높았다[41]. 따라서 이형성증이 동반되어 있지 않더라도 장분절 바렛식도 환자에서는 내시경 추적 검사가 필요할 수 있다.

24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사

권고안 12. 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사는 양성자펌프억제제 치료에 반응하지 않는 위식도 역류 증상의 감별 진단에 유용하다. 항역류 수술 전 위식도 역류 질환의 진단을 위해서도 24시간 보행성 식도산도 임피던스 검사가 필요하다.

근거 수준: 매우 낮음

권고 강도: 높음

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(73.3%), 대체로 동의함(24.4%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사는 위산분비억제제 치료에 반응하지 않거나 항역류 수술을 계획하는 경우 비정상적인 위산 역류 유무 및 역류와 증상과의 상관관계를 평가하는 데 유용하다. 식도산도검사를 시행할 때는 양성자펌프억제제를 중단(off therapy)하고 검사하거나, 위식도 역류 질환이 확인되었지만 양성자펌프억제제 치료에 반응이 나쁜 경우에는 양성자펌프억제제를 유지하면서(on therapy) 검사할 수 있다[42].

24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사는 비미란성 역류 질환, 역류 과민성 또는 기능성 가슴쓰림을 감별하는 데 유용하다[43-45]. 하루 1회 이상의 양성자펌프억제제 치료에 반응하지 않는 환자의 반수 이상이 역류와 증상과의 상관관계가 없는 기능성 가슴쓰림으로 확인되어 식도산도-임피던스 검사의 필요성을 시사하였다[46].

식도산노출시간

권고안 13. 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사에서 식도산노출시간 ≥ 4%는 아시아 성인에서 병적인 산역류로 판단할 수 있다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(20.0%), 대체로 동의함(68.9%), 미정(11.1%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스 검사는 위식도 역류 질환의 진단이 확실하지 않을 때 고려되며, 역류와 증상과의 상관관계를 파악할 수 있다. 역류 모니터링 검사에서는 식도의 식도산노출시간과 역류 에피소드가 환자의 역류 정도를 나타나는 데 이용된다. 식도산도 측정에서 pH 4 이하로 감소하는 시간의 분율인 식도산노출시간은 가장 재현성이 높은 측정값으로, 약물 치료와 항역류수술의 반응을 예측하는 데 이용된다[47]. 위식도 역류 질환 진단 기준에 대해서 최근 발표된 리옹 합의에서는 식도산노출시간값 4% 이하를 생리적인 정상 수준의 역류로, 6% 이상은 병적인 산역류로 제안한 바 있다[6]. 아시아인의 식도산노출시간값의 정상수준에 대한 기준을 마련하기 위해 정상인을 대상으로 한 19개의 연구를 포함하는 메타분석을 시행한 결과 산출된 아시아인의 식도산노출시간값의 정상 상한치는 3.2% (95% CI 2.7-3.9)였다 (Supplementary Fig. 7) [48]. 따라서, 이번 지침에서는 식도산노출시간값 4% 이상을 아시아인의 비정상적인 산역류 기준으로 제안하였다. 그러나 이 수치가 생리적인 정상 범위를 벗어나는 수준이기는 하나, 위식도 역류 질환 증상을 유발하는 수준의 병적 역류의 기준인지에 대해서는 추가 연구가 필요하다.

리옹 합의에서는 24시간 동안 80회 이상의 역류 발생건수가 있을 경우 비정상으로 판단할 것을 제안하였으나, 기준 이상의 역류 발생수가 임상 진단에 어떤 추가적인 의미를 가지는지에 대해서는 명확하지 않아 총 역류 횟수는 식도산노출시간값으로 명확한 진단을 내리기 어려운 환자에서 보조적인 정보로 사용될 수 있다[6]. 총 역류 횟수 중 증상과 관련된 분율인 증상점수(symptom index)와 역류 증상 연관성 (symptom association probability)은 증상과 역류의 상관 관계를 예측하는 데 유용하다[49,50].

식도내압검사

권고안 14. 식도내압검사는 식도의 연동 기능을 평가하고 다른 식도운동질환을 감별하는 데 유용하며, 특히 항역류 수술 전에는 식도내압검사를 시행할 것을 권고한다.

근거 수준: 낮음

권고 강도: 높음

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(57.8%), 대체로 동의 (37.8%), 미정(4.4%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

식도내압검사는 위식도 역류 질환이 의심되는 환자에서 식도산도검사 전 하부식도조임근의 위치를 확인하기 위해 사용한다. 이외에도 식도 연동 기능을 평가하거나 양성자펌프억제제 투여에도 반응이 없거나 불충분한 경우 식도이완 불능증, 원위식도연축(distal esophageal spasm), 식도 고압 수축(hypercontractile esophagus) 등의 식도 운동 질환 유무를 감별하는 데 도움이 된다[51]. 또한, 항역류 수술 전 식도 운동 질환을 배제하고 항역류 수술 후 삼킴 곤란 발생 가능성을 평가하기 위한 식도 체부의 예비 연동능(peristaltic reserve)을 확인할 수 있는 검사이다[52,53].

위식도 역류 질환에서 관찰될 수 있는 고해상도 식도내압검사(high-resolution manometry) 소견으로는 낮은 하부식도조임근 압력, 식도 열공탈장, 식도 연동운동 감소(esophageal hypomotility) 등이 있다[52]. 최근 발표된 리옹 합의에서는 항역류 장벽의 기능 이상이 위식도 역류 질환의 주요 병태생리라는 점에 근거하여 위식도접합부 형태와 위식도접합부 압력 (esophagogastric junction-contractile integral)을 두 가지 주요 지표로 제안하였으며[6], 이전 연구에서 낮은 위식도접합부 압력은 역류 빈도 및 산 노출 증가와 관련이 있었다[54]. 비효율적 식도 운동(ineffective esophageal motility)은 위식도 역류 질환에서 가장 흔히 관찰되는 소견으로, 역류된 위산 또는 위 내용물의 효과적인 제거 지연과 관련이 있다[52,55]. 이외에도 분절 수축(fragmented contraction), 무수축(absent contraction) 등이 관찰될 수 있으며, 역류와 증상과의 연관성이 보고되고 있다[56,57]. 그러나 낮은 하부식도 괄약근 압력과 식도 연동운동 감소를 포함하여 이러한 소견이나 지표들은 위식도 역류 질환의 진단에 특이적이지 않으며 일부는 무증상 건강인에서도 관찰된다[42,56]. 따라서 위식도 역류 질환을 진단하는 데있어 식도내압검사 결과 및 특정 지표가 갖는 유용성을 확인하기 위해서는 추가 연구가 필요하다.

임피던스 검사 지표

권고안 15. 원위부 식도의 기저 임피던스 값과 역류 후 삼킴유발 연동파 지수 등의 임피던스 검사 지표는 위식도 역류 질환의 진단에 도움을 줄 수 있다.

근거 수준: 낮음

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(11.1%), 대체로 동의 (68.9%), 미정(20.0%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

임피던스 검사가 확대됨에 따라 위식도 역류 질환의 진단 지표로서 기저 임피던스(baseline impedance) 값과 역류 후 삼킴유발 연동파 지수(post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index)의 역할이 대두되고 있다[6,58-60]. 기저 임피던스는 식도 점막 투과능을 반영하는 지표이다. 특히, 육안으로 점막 손상이 관찰되지 않는 경우에도 치밀이음(tight junction) 및 세포간 공간 손상에 따라 변화를 보이며, 치료 후에는 정상 수준으로 회복되므로 진단뿐만 아니라 치료 반응을 예측하는 데에도 활용할 수 있다[61]. 역류 후 삼킴유발 연동파 지수는 역류된 위산 또는 위 내용물의 제거능과 연관된 지표이다. 야간 기저 임피던스의 중간값(mean nocturnal baseline impedance)과 역류 후 삼킴유발 연동파 지수는 정상 대조군 또는 기능성 가슴쓰림으로부터 위식도 역류 질환을 감별하는 데유용하다[62,63].

위식도 역류 질환의 치료

체중 감량

권고안 16. 체중 감량은 과체중 또는 비만 환자에서 위식도 역류 질환의 증상을 호전시킨다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(80.0%), 대체로 동의 (17.8%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

과체중과 비만은 복강내 압력을 증가시켜 식도 열공탈장과 위식도 역류 질환을 발생시킨다[64-66]. 기저 체질량지수가 정상인 10,545명의 여성을 대상으로 한 대규모 코호트 연구에서 체질량지수가 3.5 kg/m2 이상 증가한 군에서 체질량 지수 변화가 없는 군과 비교하여 역류 증상이 발생할 위험이 높았다(odds ratio [OR] 2.80; 95% CI 1.63-4.82) [67]. 최근 보고된 체계적 문헌고찰에서도 비만인 경우가 그렇지 않은 경우와 비교하여 위식도 역류 질환 유병률이 뚜렷하게 높았다 (OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.46-2.06) [68].

위식도 역류 질환의 치료에 있어서 체중 감량의 효과는 여러 연구에서 보고되고 있다[65,69-73]. 따라서 비만이거나 과체중인 위식도 역류 질환 환자에게는 증상 조절을 위해 체중 감량이 권고된다.

양성자펌프억제제

양성장펌프억제제를 사용한 위식도 역류 질환의 초기 치료

권고안 17. 위식도 역류 질환의 초기 치료로 4주에서 8주의 1일 1회 표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제 투여를 권고한다.

근거 수준: 높음

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(77.8%) 대체로 동의 (22.2%), 미정(0.0%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제 제를 1일 1회 투여하였을 때, 미란성 역류 질환 환자의 약 70-80%, 비미란성 역류 질환 환자의 60%에서 완전한 증상 완화를 유도할 수 있다[42]. 하지만 위식도 역류 질환의 20-40%의 환자들에서는 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제제 투여에도 증상 호전을 보이지 않았다

양성자펌프억제제와 히스타민-2 수용체길항제의 비교

미란성 역류 질환 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제 투여는 히스타민-2 수용체길항제에 비해 더 우월한 증상 조절 및 점막 치유 효과를 보였다[74]. 양성자펌프억제제와 히스타민-2 수용체길항제의 효과를 비교한 메타분석에서 양성자펌프억제제를 투여한 군에서 증상 지속의 위험도비(risk ratio, RR)는히스타민-2 수용체길항제에 비해 0.67 (95% CI 0.57-0.80)로 유의하게 낮았다. 비미란성 역류 질환 환자의 경우에도 양성자펌프억제제가 히스타민-2 수용체길항제에 비해 역류 증상 완화에 더 효과적이다. 또 다른 연구 결과에서도 비미란성 역류 질환 환자에서 역류 증상 개선에 양성자펌프억제제는 히스타민-2 수용체길항제보다 더 효과적이었다(RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62-0.97) [75].

표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제 치료에 반응하지 않는 위식도 역류 질환의 치료

표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제 요법

권고안 18. 표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제에 적절한 반응을 보이지 않는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에게 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제가 효과적일 수 있다.

근거 수준: 보통

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(42.2%) 대체로 동의 (53.3%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(2.2%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제에 대한 반응이 불충분한 경우, 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제제를 아침과 저녁 식사 전에 하루에 두 번 사용하는 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제를 투여할 수 있다. 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제와 표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제를 비교한 3편의 무작위 대조 연구들을 메타분석하였을 때, 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제군에서 4주째 증상 소실 비율은 더 높았지만 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다(RR 1.31; 95% CI 0.99-1.73) (Supplementary Fig. 8). 8주째 증상 소실은 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제군에서 유의하게 더 높았으며(RR 1.29; 95% CI 1.15-1.45) (Supplementary Fig. 9), 치료에 필요한 환자수(number needed to treat)는 5.3이었다. 세 개의 연구 중 한 연구에서 8주차에 내시경적 치유를 평가하였으며 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제군에서 77.0% (77/100)에서 치유를 보여서 표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제의 58.8% (60/102)보다 유의하게 높았다[76]. 따라서, 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제제에 충분히 반응하지 않는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 표준 용량 두 배의 양성자펌프억제제가 효과적일 수 있다.

다른 양성자펌프억제제로의 전환

표준 용량 양성자펌프억제제에 대한 반응이 충분하지 않은 경우 다른 종류의 양성자펌프억제제로의 전환은 실제 임상 현장에서 흔히 행해지지만 이에 대한 증거는 제한적이다. 초기 치료에서 다른 유형의 양성자펌프억제제 간에 효과의 차이가 거의 없는 것으로 보인다. 각 양성자펌프억제제 별로 표준 용량은 오메프라졸 20 mg, 란소프라졸 30 mg, 판토프라졸 40 mg, 라베프라졸 20 mg 및 에소메프라졸 40 mg을 의미한다. 표준 용량에서 각 종류의 양성자펌프억제제의 치료 효능은 유사한 것으로 보이지만, 미란성 위식도 역류 질환 치료에서 다른 종류의 양성자펌프억제제들과 에소메프라졸을 비교한 메타분석에서는 점막 치유 및 증상 완화에서 에소메프라졸이 다른 종류의 양성자펌프억제제에 비해 약간의 이점을 보여주었다[77]. 15 개의 무작위 대조 연구들을 메타분석한 결과 에소메프라졸 40 mg은 4주 증상 완화(RR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01-1.12) (Supplementary Fig. 10) 및 8주 내시경적 치유(RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02-1.07) (Supplementary Fig. 11)에서 다른 종류의 양성자펌프억제제보다 더 효과적이었다.

양성자펌프억제제의 장기 유지 요법으로 필요 시 요법과 지속적인 매일 투여 요법 비교

권고안 19. 비미란성 역류 질환과 경한 미란성 역류 질환의 양성자펌프억제제의 장기 유지 요법으로 필요 시 요법은 지속적인 매일 투여 요법은 비슷한 효과를 보인다.

근거 수준: 보통

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의(31.1%) 대체로 동의 (57.8%), 미정(11.1%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

위식도 역류 질환의 양성자펌프억제제의 장기 유지 요법에서 필요 시 유지 요법과 지속적인 매일 투여 요법의 효과를 직접 비교한 7편의 무작위 대조 연구를 메타분석하였을 때[78-84], 치료 실패 비율은 필요 시 유지 요법이 9.4%, 지속적인 매일 투여 요법이 6.6%로 두 군간의 차이가 관찰되지 않았다 (RR 1.46; 95% CI 0.90-2.38) (Supplementary Fig. 12). 하위집단 분석을 시행하였을 때, 비미란성 역류 질환과 경한 미란성 역류 질환에서 두 군 간의 치료 실패율은 차이를 보이지 않았지만, 미란성 역류 질환의 경우 지속적인 매일 투여 요법이 필요 시 유지 요법보다 우월한 효과를 보였다(RR 4.24; 95% CI 2.32-7.77) (Supplementary Fig. 13). 또한 필요 시 유지 요법과 지속적인 매일 투여 요법에서 환자의 만족도 역시 차이를 보이지 않았지만(RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.92-1.00) (Supplementary Fig. 14), 증상 조절을 위해 지속적인 매일 투여 요법이 더 많은 알약 수를 필요로 하므로(RR -0.46; 95% CI -0.54 to -0.38) (Supplementary Fig. 15) 더 많은 비용이 들었을 것으로 추정된다. 따라서 필요 시 유지 요법과 지속적인 매일 투여 요법은 증상 조절 면에서 비슷한 효과를 보이지만, 필요 시 유지 요법이 환자의 선호도 및 비용 효과면에서 더 우월한 것으로 보여, 비미란성 역류 질환과 경한 미란성 역류 질환의 장기 유지 요법으로 필요 시 유지 요법을 권고한다.

비심인성 흉통에서 양성자펌프억제제

권고안 20. 양성자펌프억제제는 전형적인 위식도 역류 증상을 동반하는 비심인성 흉통 환자에게 권장된다.

근거 수준: 보통

권고 강도: 강함

전문가 합의: 전적으로 동의함(46.7%), 대체로 동의함(51.1%), 미정(2.2%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

위식도 역류 질환은 비심인성 흉통의 가장 흔한 원인 중 하나이지만, 진단 검사의 민감도가 낮으며 접근성이 용이하지 않아 양성자펌프억제제 검사가 진단에 주로 활용된다. 본 지침에서는 비심인성 흉통 환자에서 양성자 펌프 억제제의 효과를 평가하기 위하여 2019년 9월까지 7개의 무작위 대조군 연구를 선택하여 메타분석을 시행하였다[85-91]. 위식도 역류 양성군을 주당 1번 이상의 전형적인 증상이 있거나, 상부내시경 또는 24시간 보행성 식도산도-임피던스에 의해 확인된 경우로 정의하였을 때, 위약군과 비교해서 위식도 역류 양성군에서 양성자펌프억제제를 사용하였을 때 비심인성 흉통의 감소에 대한 오즈비는 3.61 (95% CI 2.46-5.29) (Supplementary Fig. 16)을 보여, 전형적인 위식도 역류 증상이 있거나 위식도 역류가 확인된 비심인성 흉통 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제가 효과적임을 보여주었다. 하지만, 위식도 역류 음성군에서 비심인성 흉통은 양성자펌프억제제가 도움을 주지 못하였다(OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.70-1.42) (Supplementary Fig. 17). 따라서 전형적인 위식도 역류 증상이 동반되는 비심인성 흉통 환자에서 8주 이상의 하루 두 번 표준 용량의 양성자펌프억제제 투여는 효과적인 치료 전략으로 판단된다. 하지만 전형적인 위식도 역류 증상이 동반되지 않은 비심인성 흉통 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제 투여는 현재까지 증거가 부족하다.

바렛식도에서 양성자펌프억제제의 사용

바렛식도는 하부식도를 정상적으로 둘러싸고 있는 중층 편평상피가 원주상피화생으로 적어도 1 cm 이상 대치된 것으로 정의된다[92]. 바렛식도는 식도 선암의 위험 인자로, 바렛식도가 고등급 이형성증 혹은 선암으로 진행하는 것을 억제하기 위해 양성자펌프억제제 투여가 권고되기도 한다. 3건의 환자 대조군 연구에 대한 메타분석에서 바렛식도가 고등급 이형성증 혹은 선암으로 진행에 대해 양성자펌프억 제제 투여의 오즈비는 0.36 (95% CI 0.09-1.44)이었다[93-95]. 또한 5건의 코호트 연구에 대한 메타분석에서는 바렛식도에 대한 양성자펌프억제제 투여의 위험비가 0.33 (95% CI 0.20-0.54)이었다(Supplementary Fig. 18) [96-99]. 즉, 바렛식도 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제를 투여할 경우 고등급 이형성증 혹은 선암으로 발전할 위험성을 약 65%가량 감소시킬 수 있음을 의미한다. 그러나, ‘바렛식도 환자에게 고등급 이형성증 혹은 선암으로의 진행 위험을 낮추기 위해 양성자펌프억제제 투여가 권유된다’라는 권고안은 전문가 투표를 거쳐 기각되었다. 바렛식도 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제의 투여가 고등급 이형성증 혹은 선암 예방효과가 여러 연구에서 입증되었음에도 불구하고, 이전 연구들이 모두 미국, 유럽, 오스트레일리아와 같은 서구권 국가에서 시행되었기 때문에 기존 연구의 결과를 아시아의 바렛식도 환자에게까지 일반화하기는 어려웠기 때문이다. 또한 아시아에서는 바렛식도의 유병률이 상대적으로 낮고 대부분의 바렛식도는 단분절형으로 서양과는 차이를 보인다[16]. 따라서 아시아의 바렛식도 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제의 영향에 대해서는 향후 추가 연구가 필요하다.

양성자펌프억제제 사용의 잠재적 위험

위산분비 억제 효과 때문에 양성자펌프억제제의 사용은 비정상적인 장내 세균 증식을 유도하고 Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli 및 Clostridium difficile과 같은 세균의 감염을 증가시킬 수 있다[100]. 또한 3년간 매일 40 mg의 판토프라졸을 복용한 경우 대조군에 비해 유의한 장관감염의 증가를 보였다 (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.01-1.75) [101]. 반면 심근경색, 뇌졸중, 암, 입원, 폐렴, 골절, 만성신장질환, 치매 등 기타 이상반응의 발생률은 약제 사용군과 대조군 간에 유의한 차이가 없었다.

양성자펌프억제제와 Clostridium difficile 감염 발생 간의 연관성에 대한 16개의 코호트 연구 결과에 대한 메타분석에서 양성자펌프억제제의 사용은 Clostridium difficile 발생의 증가와 유의한 관련성이 있었다(OR 2.03; 95% CI 1.52-2.72) (Supplementary Fig. 19). 그러나 Clostridium difficile 감염 발생률은 앞서 언급된 장관 감염 발생률보다 훨씬 낮기 때문에 치료에 필요한 환자수는 장관 감염 보다는 더 클 것으로 보여, 치료 적응증에 맞게 사용한 경우 이득이 위해를 상회한다고 볼 수 있다. 종합하면, 양성자펌프억제제의 사용은 장관 감염 및 Clostridium difficile 감염의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있지만 위험의 증가는 매우 작은 것으로 생각되므로 올바른 적응증에 사용한다면 이득이 위해보다 커 보인다. 그렇지만 가능하다면 효과를 볼 수 있는 최소 용량과 기간으로 양성자 펌프억제제를 사용하는 것이 바람직할 것으로 생각된다. 양성자펌프억제제의 장관 감염 및 Clostridium difficile 감염 위험성에 대한 권고문은 1차 투표에서는 62.2%의 전문가만이 동의하였고, 2차 투표에서는 65.1%의 전문가만이 동의하여 기각되어 이와 관련된 권고안은 채택되지 않았다.

칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제

권고안 21. 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제는 양성자펌프억제제와 대등한 효과로 위식도 역류 질환의 초기 치료로 권고된다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 등급: 강함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(66.7%), 대체로 동의함(33.3%), 미정(0.0%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(0.0%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제는 양성자펌프의 칼륨 부착 부위에 경쟁적, 가역적으로 결합하여 작용을 억제하는 약물로 1980년대에 처음 개발되었다[102]. 그러나 초기의 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제는 양성자펌프억제제보다 우월한 효과를 보여주지 못하였으며 간 독성 부작용으로 개발이 중단되었다[103]. 현재까지 진행된 3편의 무작위 비열등 연구 결과, 미란성 역류 질환에서 vonoprazan의 효과는 lansoprazole과 비교하여 열등하지 않음을 보여주었다[104-106]. 또한 최근의 네트워크 메타분석에서는 vonoprazan이 rabeprazole보다 미란성 역류 질환의 치유율에서 우월한 효과를 나타냄을 보여주었다[107].

Tegoprazan은 한국에서 개발되어 현재 미란성 역류 질환과 비미란성 역류 질환에 사용되고 있으며, 최근의 3상연구에서는 tegoprazan이 esomeprazole과 대등한 효과와 안정성을 나타냄을 보여주었다[108].

Vonoprazan과 tegoprazan을 대상으로 한 4개의 무작위 대조 연구를 메타분석한 결과[104-106,109], 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비 억제제의 8주째 미란성 역류 질환의 치유율은 양성자펌프억제제와 대등한 결과를 보였으며(RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.99-1.04) (Supplementary Fig. 20), 단기간 부작용의 발생률은 차이를 보이지 않았다. 이 결과로부터 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제의 4주째와 8주째 미란성 역류 질환의 치유율은 양성자펌프억제제와 대등하므로, 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제도 위식도 역류 질환의 초기 치료로 사용될 수 있다.

LA classification C, D의 심한 미란성 역류 질환에서 vonoprazan과 양성자펌프억제제를 비교분석한 결과에서는, vonoprazan이 양성자펌프억제제보다 우월한 결과를 보여주었다[104-106]. Tegoprazan에서는 비록 환자 수가 적어 하위그룹 분석은 없었으나, 심한 미란성 역류 질환에서 100%의 높은 치유율을 보여주었다[109]. 이러한 결과들로 볼 때, 비록 근거는 부족하지만 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제가 심한 미란성 역류 질환에서 양성자펌프억제제보다 그 효과가 우월할 수 있음을 시사한다. 향후 위식도 역류 질환에서 칼륨경쟁적 위산분비억제제의 장기 유지 요법의 효과나 장기 안전성에 대한 연구가 필요하다.

야간산분비돌파 환자에서 히스타민-2 수용체길항제의 추가 요법

양성자펌프억제제를 투약하는 상황에서, 야간에 위내 산도가 4 미만으로 한 시간 이상 유지되는 현상을 야간산분비 돌파 또는 야간산분비 억제실패라고 한다[110]. 양성자펌프억제제가 짧은 반감기를 갖거나, 양성자 펌프의 재생 능력이 뛰어난 경우 아침 식전에 한번 투여하는 표준요법으로는 야간의 위산분비 억제에 한계가 있을 수 있다. 8개의 무작위 대조군 연구 결과를 메타분석한 결과, 취침 전 히스타민-2 수용체길항제의 추가 투여를 통해 야간산분비돌파의 빈도를 감소시켰다[111]. 그러나 분석에 포함된 연구 대상자 수가 제한적으로 연구의 결과를 일반화시키기엔 근거가 취약한 점이 있다. 또한 히스타민-2 수용체길항제는 일정 투여 기간 후에 효과가 감소하는 속성내성(tachyphylaxis)으로 사용에 제한점이 있다[112]. 따라서, 히스타민-2 수용체길항제를 취침 전 추가하는 것은 양성자펌프억제제의 투여에도 불구하고 야간 역류 증상이 있거나 야간 식도 역류의 객관적인 증거가 있는 일부 환자에서 선택적으로 시도해 볼 수 있겠다.

위장관운동촉진제

위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 위장관운동촉진제가 위식도 역류 질환 증상을 개선하는 데 효과적이라는 연구들이 있다[113-115]. 양성자펌프억제제 단독 요법에 비해 양성자펌프억제제에 위장관운동촉진제를 병용 투약하였을 때의 증상 개선에 대한 9편의 연구에 대한 메타분석에서 양성자펌프억제제 단독 요법의 증상 개선은 50.6%, 양성자펌프억제제에 위장관운동촉진제를 병용하였을 때 증상 개선은 63.8%로, 양성자펌프억제제에 위장관운동촉진제를 병용할 때 증상 개선이 더 효과적이었다. 그리고 위식도 역류 질환의 전반적인 증상을 줄이는 데 양성자펌프억제제와 위장관운동촉진제를 병용 투여하였을 때 통계적으로 유의한 효과가 있었다(RR 1.22; 95% CI 1.11-1.35, I2= 15%, p= 0.310) (Supplementary Fig. 21). 난치성 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 양성자펌프억제제와 위장관운동촉진제를 함께 투여하면 양성자펌프억제제 단독 요법보다 유의하게 더 나은 증상 개선을 보였다(RR 1.47; 95% CI 1.15-1.88, I2= 0%, p= 0.510) (Supplementary Fig. 22). 따라서 위식도 역류 질환 환자의 증상을 개선하기 위해 양성자펌프억제제와 위장관운동촉진제를 함께 투여할수 있다. 하지만, 각각의 메타분석에 포함된 연구들이 비교적 작은 표본 크기를 가지고 다양한 방법으로 치료 효과를 분석하여 연구 결과의 제한점이 높다. 따라서 전문가 합의는 위식도 역류 질환 환자의 증상 개선을 위해 양성자펌프억제 제에 위장관운동촉진제를 병용하는 것에 대한 합의에 도달하지 못하였다.

Baclofen

Baclofen은 γ-aminobutyric acid 수용체 작용제로, 일과성 하부식도조임근 이완과 역류 횟수를 감소시키므로 위식도 역류 질환 치료에 사용할 수 있다[116-119]. Baclofen은 식후 산역류 및 비산역류 횟수, 약간 역류와 트림 횟수를 감소시키는 데도 효과가 있다[120,121]. 하루 2회 양성자펌프억제제에도 반응이 없는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에게 baclofen 5-20 mg 하루 3회 투여를 고려해 볼 수 있다[122]. Baclofen 사용 후 어지러움, 피로, 졸음과 같은 신경학적 부작용이 보고되었으나 baclofen 사용으로 인한 심한 부작용이나 사망은 없었다. Baclofen의보고된 모든 부작용은 경도 내지 중등도 수준이었다.

Alginate

Alginate는 갈색 해조류로부터 얻을 수 있는 음이온성 고분자 물질로, 위산과 반응하여 위산 역류를 방해할 수 있는 물리적 장벽을 형성하여 위산 역류를 감소시킨다[123]. 위산 주머니(acid pocket)란 식후에 섭취한 내용물의 위쪽으로 산도가 매우 낮은 산층이 형성되는 현상으로, 식후 위산 역류를 일으키는 원인이 된다[124]. 한 연구에서는 alginate가 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 위산 주머니를 제거하거나 감소시킬 수 있다고 보고하였으며[125], 또 다른 연구에서도 alginate가 역류와 연관된 증상 개선에 효과적이며, 다른 제산제와 비교하여서도 더 나은 효과가 있음을 입증하였다[126,127]. 메타분석에서, alginate나 제산제는 위약에 비해 60% 정도 증상 개선 효과가 있음을 입증하였고[128], 한 무작위 대조군 연구에서는 비미란성 역류 질환에서 alginate와 양성자펌프억제제의 효과가 유사함을 보고하였다[129]. 따라서 alginate는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 유용하게 사용할 수 있는 약제라고 할 수 있겠다.

내시경 치료

위식도 역류 질환의 내시경 치료는 약물 요법에 반응하지 않는 환자에서 수술적 위추벽성형술 전에 시도해 볼 수 있는 최소침습치료법이다. 내시경 치료법은 1) 내시경적 위추벽 성형술(endoscopic fundoplication), 2) 내시경적 고주파 에너지 전달(endoscopic radiofrequency procedure; Stretta®), 3) 항역류 내시경 점막절제술(anti-reflux mucosectomy)의 3가지 카테고리로 분류된다. 최근 2,468명의 Stretta의 임상적 결과에 대한 메타분석 결과에서는 평균 25.4개월의 추적 기간 동안 Stretta가 건강 관련 삶의 질 점수를 개선하고, 통합 속쓰림 점수, 미란성 식도염 발생률, 식도산노출 및 양성자펌프억제제의 사용을 감소시키는 것으로 나타났다[130]. 그러나 28개의 연구 중 4개의 무작위 대조 연구에서 복강경 니센 위추벽 성형술 등의 다른 시술과 비교하지 않았다는 제한점이 있다. Stretta 전후 217명의 환자를 대상으로 한 장기 관찰 연구에서 위식도 역류 질환의 삶의 질 점수, 만족도 및 양성자펌프 억제제의 사용이 크게 개선되었고, 그 효과는 바로 나타났으며 10년까지도 지속되었다[131]. 그러나 위식도 역류 질환 환자 153명을 대상으로 한 또 다른 메타분석에서 Stretta는가짜치료(sham therapy)와 비교하여 pH < 4, 하부식도 괄약근 압력, 양성자펌프억제제 중단 또는 삶의 질을 포함한 생리적 매개변수에서 유의한 변화를 보이지 않았다[132]. 위식도 역류 질환에 대한 대부분의 내시경 치료의 장기 결과는 아직 불분명하다. 따라서 내시경 치료는 선택된 환자에서 신중하게 고려되어야 한다.

항역류수술

권고안 22. 항역류수술은 위식도 역류 질환 환자의 증상 치료 및 삶의 질 개선을 위해 양성자펌프억제제의 대체 치료로 사용할 수 있다.

근거 수준: 중등도

권고 강도: 약함

전문가 의견: 전적으로 동의함(22.2%), 대체로 동의함(60.0%), 미정(15.6%), 대체로 동의하지 않음(2.2%), 전적으로 동의하지 않음(0.0%)

항역류수술은 현재 위식도 역류 질환의 효과적인 치료 방법 중 하나로 인정받고 있다. 몇몇 전향적 연구에서 항역류수술은 양성자펌프억제제의 치료보다 낮은 식도 위산노출 및 높은 하부식도 괄약근 압력 유지를 보여주고 있다[133-135]. 항역류수술과 약물 치료의 비용 효과를 비교한 연구에서는 중장기적으로 항역류수술이 비용 효과적인 이익을 가지고 있음을 보여주기도 하였다[132]. 최근 국내의 한 연구에서도 항역류수술이 장기적으로 양성자펌프억제제 사용에 비해 비용 절감 및 효과적인 위식도 역류의 치료 결과를 가지고 있음을 보고하였다[136]. 항역류수술의 적응이 되는 적합한 환자군을 잘 선택한다면 우수한 장기 치료 효과 및 비용 효과를 볼 때 양성자펌프억제제의 대체 치료 방법으로 사용을 추천할 수 있다.

결론 및 제언

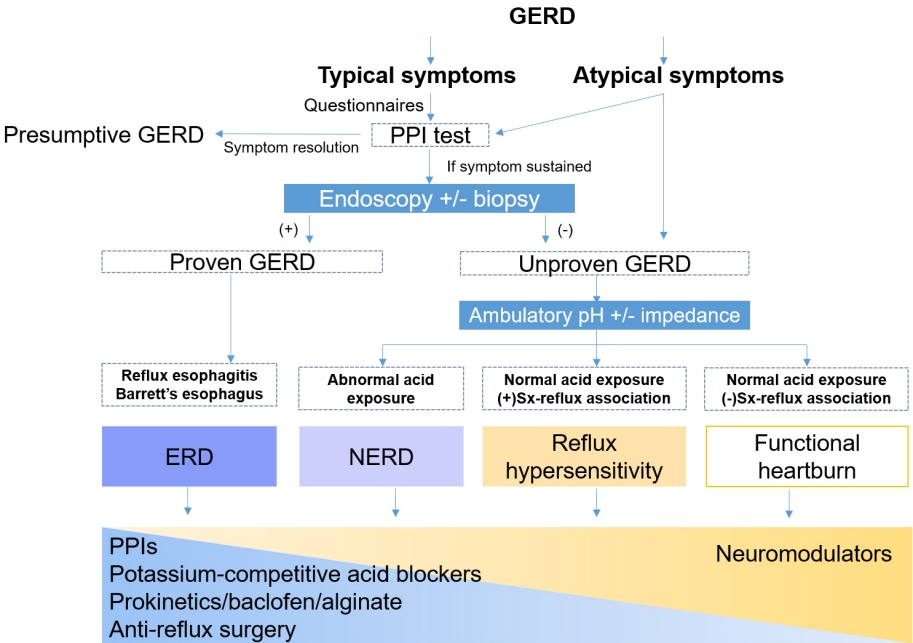

위식도 역류 질환에 관한 서울 진료지침 2020은 체계적인 문헌 검토 및 메타분석 방법을 통해 아시아 전문가와의 협업을 통해 개발되었다. 아시아에서 위식도 역류 질환의 유병률이 빠르게 증가하고 있으므로 새롭게 제시된 여러 연구자료를 바탕으로 만들어진 이번 지침이 아시아에서의 위식도 역류 질환에 대한 진단 및 치료에 새로운 표준을 제시해 줄 수 있을 것으로 기대된다(Fig. 2). 향후 위식도 역류 질환의 새로운 진단 지표들의 검증이 이루어지고, 새로운 약물들이나 비약물적 치료에 대한 연구 결과들이 더 많이 축적되면 본 진료지침의 개정이 이루어질 예정이다.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

This project was supported by the KSNM and a grant of Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI19C0481 and HC19C0060).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hye-Kyung Jung and Chung Hyun Tae have contributed in writing and editing the paper as the first authors; Mi-Young Choi helped in formulating clinical key questions, conducting relevant literatures search, and mentoring for extensive meta-analyses. Jong Kyu Park, Seung Joo Kang, Jung Min Lee, Seung Young Kim, Chan Hyuk Park, Da Hyun Jung, Joon Sung Kim, and Seung In Seo performed the meta-analysis, the extraction of recommendations, and writing the paper; Kyung Ho Song, Jeong Eun Shin, Hyun Chul Lim, Yoon Jin Choi, Beon Jin Kim, Sun Hyung Kang, Tae Hee Lee, Young Sin Cho, Eun Jeong Gong, Han Hong Lee, Kee Wook Jung, Do Hoon Kim, and Hee Seok Moon have contributed in the systematic review, the extraction of recommendations, and writing the paper; Sang Kil Lee, Suck Chei Choi, Joong Goo Kwon, Kyung Sik Park, Moo In Park participated in interpretation of data; and Hye-Kyung Jung and Kwang Jae Lee have designed the guideline development as chairman of the guideline committee and KSNM, respectively, and have revised the manuscript critically.

Supplementary Materials

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the systematic review process of the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia.

Forest plot comparison of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in population-based studies for 2 periods, 2000-2009 and 2010-2019. ES, effect size.

Forest plot comparison of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in observational studies of subjects who underwent medical check-ups in 2000-2009 and 2010-2019. ES, effect size.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the systematic review process of the diagnostic performance of empirical proton pump inhibitors in gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Forest plot of sensitivity and specificity in a trial of proton pump inhibitors.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis of dose (single versus double) and duration (< 2 weeks versus > 2 weeks) of proton pump inhibitors.

Forest plot of upper limits of normal for the acid exposure time (AET [%]) in Asian studies.

Forest plot of symptom resolution in the double and standard dose proton pump inhibitor at 4 weeks in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of symptom resolution in the double and standard dose proton pump inhibitor at 8 weeks. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of symptom relief in subjects on esomeprazole 40 mg per day and other standard dose proton pump inhibitors at 4 weeks. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of symptom relief in subjects on esomeprazole 40 mg per day and other standard dose proton pump inhibitors at 8 weeks. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of risk ratios of failure between on-demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and continuous PPI groups in long-term management. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of risk ratios of failure between on-demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and continuous PPI groups in long-term management according to each subgroup analysis. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; EE, erosive esophagitis. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of the satisfaction between the on-demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and continuous PPI groups in long-term management. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of medication use between on-demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and continuous PPI groups in long-term management.

Forest plot of the benefits from the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment in gastroesophageal reflux disease positive patients with non-cardiac chest pain. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of the benefits from the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment in gastroesophageal reflux disease negative patients with non-cardiac chest pain. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Forest plot of the odds ratio of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medication in the risk of progression into high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

Forest plot of the odds ratio of proton pump inhibitor medication in the risk of Clostridium difficile infection.

Forest plot of the risk ratio of potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) in erosive esophagitis healing rates at 8 weeks. PPI, proton pump inhibitor. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.