영양, 대사 및 감염에 미치는 프로톤펌프억제제의 영향: Unsafe 측면

The Effects on Nutrition, Metabolism and Infection by Proton Pump Inhibitors: Unsafe Perspective

Article information

Trans Abstract

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) are very effective drug used frequently in acid-related disorders. Long-term use of PPI is becoming increasingly common, often without appropriate indications. The debate had focused on the adverse effects related to long-term use of PPI during the last years. This article is a detailed review of the evidence on this topic, focusing on the adverse effects of long-term PPI use that have developed the greatest concern; vitamin B12 deficiency, iron deficiency, impaired calcium absorption, bony fracture, hypomagnesemia, increased susceptibility to pneumonia and enteric infections. Although PPIs have been used with a high margin of safety, the clinicians should consider reducing the dose of PPIs and reassessing the treatment duration to prevent adverse effects of PPIs. (Korean J Med 2011;81:17-25)

서 론

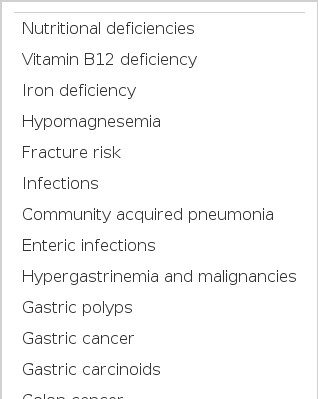

위산 분비를 적절하게 조절하면 식도, 위, 십이지장의 여러 질환에서 조기에 증상을 없애고, 질환을 치유하며 합병증을 예방할 수 있다. 위산분비억제제로는 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제와 항콜린제 등이 먼저 개발되었으나, 1979년 스웨덴에서 프로톤펌프억제제(Proton pump inhibitors, PPI)가 개발되어 1988년 omeprazole이 시판된 이후 위산의 분비 억제에 가장 효과적인 약제로 현재까지 위산 연관 소화기 질환(소화성 궤양, 출혈성 궤양, 위식도역류질환, Helicobacter pylori 제균 치료 등)에 사용되고 있다[1]. 그러나 최근 위식도역류질환의 유지요법을 포함하여 장기적인 프로톤펌프억제제 사용이 증가함에 따라[2], 약제의 안전정 문제가 주목을 받고 있으며, 이와 관련하여 약제의 부작용에 대한 여러 보고가 발표되고 있다(Table 1) [3]. 또한 몇몇 연구에서는 입원 환자의 50-60%에서 프로톤펌프억제제가 적절한 투여기준 없이 사용되고 있다고 보고하여 프로톤펌프억제제의 과다한 사용 문제를 언급하고 있다[4-6]. 프로톤펌프억제제로 인한 부작용의 원인은 위벽세포에서 산분비를 억제하는 직접적인 효과, 간의 cytochrome P450과 상호작용으로 인한 효과, 그리고 면역억제의 효과 등에 의한 것이다[7]. 본 장에서는 프로톤펌프억제제의 장기적인 복용과 관련된 부작용 중 영양, 대사 및 감염에 미치는 영향을 살펴보고자 한다.

본 론

프로톤펌프억제제의 작용기전

프로톤펌프억제제는 경구로 투여하는 경우에 근위부 소장에서 흡수된 후, 혈류를 통해 위벽세포의 기저세포막을 통과하여 벽세포 내로 들어가며, 정맥으로 투여하면 바로 혈류를 따라 벽세포에 도달한다[8]. 벽세포의 세포막을 통과한 프로톤펌프억제제는 전구약물 형태로 세포 내로 들어가 축적되며 위산에 의해 활성체인 설포나마이드(sulfonamide)로 바뀌게 된다. 이 활성체가 세포막 내에 존재하는 프로톤 펌프의 H+-K+-ATPase와 결합하여 불활성화함으로써 산분비를 억제한다[1]. 이 결합은 비가역적으로 일어나며 산분비능의 회복은 새로운 H+-K+-ATPase가 만들어진 후 가능하다. 프로톤펌프억제제의 장기적인 복용은 위산 분비 양을 감소시키고, 그 결과로 위 산도의 기저치가 증가하게 되어 위 전정부 점막에 있는 D 세포로부터 소마토스타틴(somatostatin) 분비가 억제된다[9,10]. 이로 인해 G 세포로부터의 가스트린(gastrin) 분비가 억제되지 않아 혈중 가스트린이 증가하게 된다.

비타민 B12 결핍

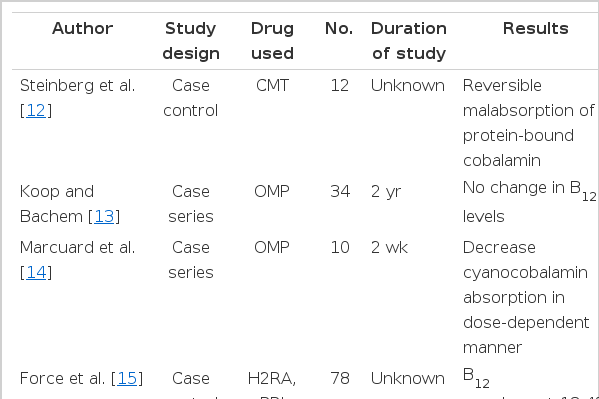

비타민 B12는 정상적으로 단백질과 결합된 상태로 섭취된다. 이 단백질과 분리되기 위해서는 위산과 펩신(pepsin)이 필요하다. 단백질과 분리된 후, 벽세포와 침샘세포에서 분비되는 R 단백(R protein)과 결합하여 십이지장으로 이동한다. 십이지장에서 췌장효소(pancreatic enzymes)가 R 단백-비타민 B12 결합체를 절단하고, 위의 벽세포에서 분비된 내인자(intrinsic factor)와 비타민 B12가 결합한다. 이 내인자-비타민 B12 결합체가 회장에서 흡수된다[11]. 위산이 감소되면 음식물 섭취 후 단백질과 비타민 B12가 분리되지 못하여, 비타민 B12의 흡수장애를 유발할 수 있으며, 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제를 사용하였을 때 단백결합 비타민 B12의 흡수가 감소되었다[12]. Omeprazole에 의한 비타민 B12 흡수장애에 대한첫 연구에서는 비타민 B12의 변화가 관찰되지 않았으나[13], 건강한 남성 10명에게 2주간 omeprazole을 투약한 후, 투약 전후에 cyanocobalamin 흡수를 확인한 결과, omeprazole 20 mg을 복용하였을 경우에는 cyanocobalamin 흡수가 3.2%에서 0.9%로 감소하였고(p= 0.031), 40 mg 복용군에서는 3.4%에서 0.4%로 감소 폭이 더욱 증가하였다(p< 0.05) [14]. 후향적 환자-대조군 연구에서도 비타민 B12 보충은 만성적인 위산 억제 치료와 연관이 있었고(p= 0.025; OR 1.82; 95% CI, 1.08-3.09), 만성적인 프로톤펌프억제제의 복용은 혈청 비타민 B12의 농도를 감소시켰다[15]. Omeprazole로 치료받은 Zollinger-Ellison 증후군 환자 110명과 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제를 사용한 환자 20명에서 각각 비타민 B12와 엽산의 수치를 측정하였을 때, 엽산은 양군에서 차이가 없었으나, 비타민 B12는 omeprazole로 치료받은 군에서 의미있게 감소되었다(p= 0.03). 이 연구에서 위산억제 치료기간은 평균 4.5년이었다. 또한, 혈청 비타민 B12의 감소 전에 오는 무증상의 변화를 평가하기 위해 methylmalonic acid와 homosysteine의 수치를 측정하였을 때, 장기간의 프로톤펌프억제제를 복용하는 환자 31%에서 무증상의 비타민 B12 결핍이 관찰되었다[16,17]. 비타민 B12 결핍은 고령에서 더 흔하게 발생되는데, 이에 대한 두 개의 후향적 연구에서 장기간의 위산 억제와 비타민 B12 결핍과의 연관성을 제시하였다[18,19]. 하지만 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용과 비타민 B12 결핍 간에 연관성이 없다는 연구결과도 있는데, 3년 이상 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 65세 이상 환자 125명을 대상으로 한 연구에서 장기간 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 환자들과 그들의 배우자 사이에 비타민 B12의 평균수치에 차이가 없었다(p= 0.73) [20].

위에서 살펴본 바와 같이 여러 연구에서 프로톤펌프억제제와 비타민 B12 결핍과의 연관성을 제시하고 있다(Table 2). 하지만 현재까지의 증거는 대개 소규모, 비무작위, 후향적 연구들을 토대로 하였으며, 향후 대규모의 전향적인 연구가 필요한 상태이다.

철분 결핍

식이성 철분은 환원 헴철(heme iron) 또는 비환원 헴철로 존재하며, 비환원 헴철의 흡수는 위산이 있는 경우에서 가장 효과적으로 이루어진다[21]. 오랜 기간 동안 위산 분비가 감소된 상태에서 임상적으로 의미 있는 철분의 흡수장애가 보고되었는데, 무산증(achlorhydria) 환자와 여러 위산 분비저하 상태(위절제, 미주신경절제, 위축성 위염)의 경우에 비환원 헴철의 흡수가 감소되었다[22,23]. 하지만 장기간 위산분비억제제를 복용한 109명의 Zollinger-Ellison 증후군 환자들을 대상으로 저장철과 철분결핍성 빈혈여부를 평가한 연구에서 6년 동안 omeprazole로 치료받았거나 10년 동안 위산분비억제제를 복용한 경우에 저장철의 감소나 철분 결핍은 관찰되지 않았다[24]. 또한, 34명의 소화성궤양 환자에서 omeprazole을 투여했을 때 철분 결핍의 위험도가 증가되지 않았다[13]. 임상 연구를 통해 확인되지는 않았지만, 이론적으로 위산분비억제제를 장기간 복용하였을 때 철분의 흡수장애가 발생할 가능성이 있으므로 장기적으로 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용하는 경우에 철분 결핍에 대한 감시를 고려할 수 있다. 프로톤펌프억제제와 철분결핍과의 연관성을 확립하기 위해서는 Zollinger-Ellison 증후군이 없는 일반 환자들을 대상으로 한 대규모 연구가 필요한 상태이다.

칼슘 흡수장애

위산은 칼슘의 흡수에 관여하는 중요한 인자이며[25], 무산증이 있는 경우에 소장에서 칼슘 흡수 장애가 생긴다[26]. 칼슘의 흡수에는 용해도가 중요한데 위장관에서 산도가 유지되어야 비용해성 칼슘염(calcium salt)으로부터 칼슘이온이 쉽게 분리된다[27]. 따라서 위와 근위부 소장에서 적절한 산도가 유지되지 않으면 칼슘이 체내로 흡수되는 과정이 방해를 받는다. 칼슘 흡수에 장애가 생기면 혈중 칼슘이온의 수치가 떨어지게 되고 이를 보상하기 위하여 이차성 부갑상선기능항진증이 발생하게 된다. 이로 인해 부갑상선호르몬의 분비가 증가하면 골 재흡수를 촉진하여 부족한 칼슘을 보충하게 된다. 이러한 부갑상선기능항진증이 지속되게 되면골밀도의 감소가 일어나고, 결국은 골절의 위험도를 증가시키게 된다[11,28].

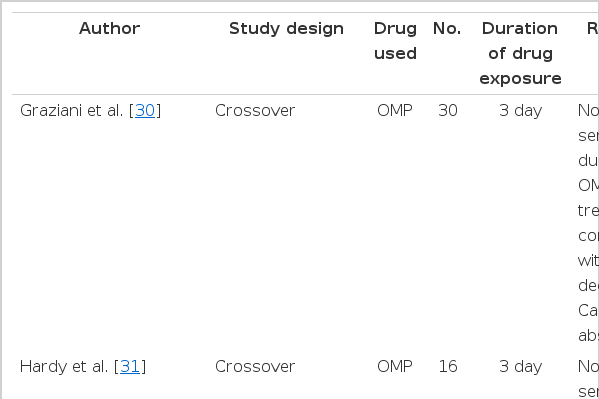

프로톤펌프억제제와 칼슘의 흡수장애에 관한 연구는 그리 많지 않은데(Table 3), 프로톤펌프억제제를 복용시킨 쥐에서 칼슘의 흡수가 감소되었다[29]. 혈액투석 환자를 대상으로 한 두 연구에서는 omeprazole을 복용한 경우와 복용하지 않는 환자에게 칼슘제를 복용시킨 후 혈액내 칼슘수치를 측정하여 칼슘의 흡수정도를 비교하였는데, omeprazole을 복용하는 환자군에서는 칼슘의 혈중 농도가 상승되지 않았다[30,31]. 건강한 남자 8명을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 칼슘의 흡수를 촉진시키기 위해 7일간 저칼슘 식이요법을 시행한 후 칼슘 1 g을 복용시켜 식후 혈중 칼슘 농도를 측정하였는데, 이 역시 위약군에서는 식후 혈중 칼슘 농도가 의미 있게 증가한 반면, omeprazole 복용군에서는 증가하지 않았다[32]. 하지만 이 연구들은 간접적으로 칼슘의 흡수 정도를 측정하였다는 단점이 있다.

현재까지 프로톤펌프억제제와 칼슘의 흡수장애에 관한 무작위 대조 연구는 두 개가 있다. O’Connell 등[33]은 45Ca 동위원소를 붙인 탄산칼슘(calcium carbonate)를 이용하여 65세 이상의 여자 환자 18명을 대상으로 omeprazole이 분획 칼슘 흡수(fractional calcium absorption)에 미치는 영향을 조사하였는데, omeprazole을 복용한 군에서 대조군에 비해 칼슘 흡수율이 평균 41% 낮았다. 이 연구는 방사선 동위원소를 이용하여 분획 칼슘 흡수를 직접 측정하여 프로톤펌프억제제와의 연관성을 확인한 첫 연구이다. 하지만 연구가 공복상태에서 진행되었고, 공복상태에서 흡수가 덜 효과적인 탄산칼슘을 사용하였다는 제한점이 있다. 다음 연구에서는 장세척 방법으로 omeprazole이 칼슘의 흡수에 미치는 효과를 평가하였다. 장세척을 먼저 시행한 후, 4시간의 휴식기를 지내고 시험 식이를 먹게 한 후 12시간 뒤에 다시 장세척 방법으로 시험 식이를 채취하여 흡수되지 않은 칼슘의 양을 측정하였다. 13명의 환자를 대상으로 omeprazole을 복용한 군(n = 5)과 대조군(n = 8)으로 나누어 연구를 진행하였는데, 이 연구에서는 양 군 간에 분획 칼슘 흡수에 차이가 없었다[34].

현재까지의 연구결과들을 살펴보면, 프로톤펌프억제제의 복용으로 인해 칼슘 흡수장애가 발생할 수 있다. 하지만 연구들마다 여러 제한점을 가지고 있는 상태이므로 칼슘 대사에 영향을 줄 수 있는 나이, 성별, 폐경 유무 등을 고려하여 잘 고안된 연구가 필요한 상태이다.

골절의 위험

위에서 살펴본 대로, 위산분비 억제는 칼슘과 비타민 B12의 흡수장애를 초래할 수 있다. 비타민 B12는 골모세포(osteoblast) 활성도 및 골형성과 관련이 있는데, 비타민 B12의 경미한 감소에도 골다공증의 위험성이 약 4.5배 증가하고, homocystinemia를 유발하여 골절을 조장할 수 있다[35]. 덴마크에서 2000년 한 해에 발생한 모든 골절 증례를 평가한 연구에서 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 경우에 골절의 위험도가 상승하였고(OR 1.18; 95% CI, 1.12-1.43), 분석범위를 고관절 골절(OR 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65)과 척추 골절(OR 1.6; 95% CI 1.25-2.04)로 제한하였을 경우에는 위험도가 더 높았다. 다른 연관된 인자로는 제산제(OR 1.33)와 비스테로이드성 소염제(OR 1.16) 사용 및 위절제(OR 1.96)가 있었다[36]. 영국에서 1985년부터 2003년 사이에 발생한 고관절 골절의 증례들을 수집하여 1년 이상 프로톤펌프억제제 또는 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제를 사용한 경우를 따로 분석하였는데, 프로톤펌프억제제와 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제를 사용한 경우 모두에서 고관절 골절의 위험도가 증가하였다(프로톤펌프억제제 OR 1.44, 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제 OR 1.23). 또한, 1년 이상 장기간 고용량을 복용한 경우에 더욱 골절 위험도가 높았다(OR 2.65) [37]. 마지막으로 1996년부터 2004년까지 고관절, 손목, 척추 골절이 발생한 50대 이상의 환자들을 대상으로 진행된 후향적, 환자-대조군 연구에서 골다공증과 연관된 골절 위험도는 프로톤펌프억제제를 7년 이상 사용한 환자들에서 더 높았다(OR 1.92, 95% CI, 1.16-3.18) [38]. 장기간의 프로톤펌프억제제 사용과 골절 위험도와의 연관성을 조사한 연구들은 아직은 수가 적고, 또한 비무작위 연구이지만, 실제 임상에서 주지하고 있어야 할 부작용 중 하나로 생각한다.

저마그네슘혈증

최근 장기간 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용하고 있는 환자에서 저마그네슘혈증이 발생한 7명의 환자가 보고되었다[39-42]. 마그네슘의 항상성은 장내흡수와 신배출(renal excretion) 사이의 균형으로 유지되는데, 마그네슘의 장내 이동과 신장내 이동에 연관되는 transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) 6와 TRPM7이라는 이온 통로(ion channel)는 장내 pH의 상승을 포함한 여러 요소들에 영향을 받는다[43,44]. 하지만 장기적인 프로톤펌프억제제의 사용으로 인해 발생한 저마그네슘혈증의 빈도와 그 기전에 대해서는 아직 명확하지 않다.

감염

위산은 섭취된 병원체에 대한 주요 방어기전으로 작용하고, 위산의 감소는 정상적으로 무균상태로 유지되는 상부위장관에서의 세균집락(colonization)과 관계된다[45]. 또한 프로톤펌프억제제는 호중구의 기능을 저해하여 세균 감염의 위험성을 조장할 수 있다[46,47]. 따라서 프로톤펌프억제제에 의해 유발된 위산의 감소는 여러 감염 질환에 관여될 수 있는데, 주로 보고되고 있는 질환으로는 호흡기 감염(지역사회성 폐렴 및 병원감염성 폐렴)과 세균성 장염, 그리고 Clostridium difficile 장염 등이 있다.

호흡기 감염

스트레스성 궤양을 예방하기 위해 중환자실의 환자들에게 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제와 프로톤펌프억제제가 많이 사용되고 있으며, 1996년 시행된 메타분석에서 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제의 사용이 위약에 비해 더욱 효과적이었다[48]. 하지만 이러한 위산분비억제제의 사용은 폐렴, 특히 기계호흡 연관성 폐렴을 증가시킬 수 있다. 기계호흡을 하는 경우에서는 분비물이 구강인두부와 설하부위로 많이 모여있게 되고, 이 분비물들이 쉽게 하부 기도로 흡인될 수 있는데, 위산분비가 억제된 상태에서는 위내 그람음성균이 증가하고, 이 병원체들이 구강인두부와 설하부위에 집락화될 가능성이 높아지기 때문에 흡인성 폐렴의 발생가능성이 증가하게 된다[49,50]. Faisy 등[51]의 연구에서는 스트레스성 궤양 예방요법이 중환자실 환자들에서 임상적으로 위장관 출혈에 영향을 주지 못하였고, 또한 스트레스성 궤양의 고위험군 환자(48시간 이상의 기계호흡, 혈액응고장애)를 287명을 대상으로 시행한 무작위, 환자-대조군 연구에서도 프로톤펌프억제제, 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제, 제산제가 위약에 비해 상부위장관 출혈 예방에 더 좋은 효과가 없었으며(p> 0.28), 병원감염성 폐렴 빈도만 증가하였다[52]. 따라서 최근에는 스트레스성 궤양에 대한 심각한 위험성이 있는 환자들에게만 제한적으로 위산분비 억제 요법이 권장되고 있다[53,54].

병원감염성 폐렴에서만이 아니라 지역사회 폐렴에 대해서도 위험성이 보고되고 있는데, 대규모 코호트 연구에서 폐렴 발생률이 위산분비 억제요법을 시행하지 않는 경우 0.6/100인년(person-year)이었고, 위산분비 억제요법을 시행한 경우에 2.45/100인년으로 상대위험도가 약 4배 높았다[55]. 다른 코호트 연구에서는 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 군에서 폐렴으로 입원할 위험도가 약 50% 증가하였다(OR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.7) [56]. 두 연구 모두에서 폐렴에 대한 정확한 진단에 부족한 점들이 있었으며 폐렴 발생과 관련된 여러 혼란 변수들에 대한 적절한 보정이 없었기 때문에 아직 결론을 내리기에는 이른 시점이나 폐렴도 프로톤펌프억제제 사용에 따라 발생 가능한 부작용의 하나로 고려해야 한다.

장내 감염

위장관 내에는 점막 상피세포와 점액층, 정상 세균총 그리고 위산과 같은 세균 감염에 대한 여러 방어기전들이 존재한다[11]. 그중 위의 산도가 감소하게 되면 정상 세균총이 변화되어 세균의 과증식(bacterial overgrowth)을 발생할 수 있다[57]. 최근 연구에서 장기간 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 환자의 50%에서 소장세균과증식(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth)이 관찰되었다[58]. 또한 장기간의 위산분비 억제요법으로 인해 위장관 감염의 발생이 증가한다는 여러 연구들이 있다. 위산분비억제제를 투여받은 소아 환자에서 급성 장염의 위험도가 증가하였다(OR 3.58; 95% CI, 1.87-6.86) [59]. Leonard 등[60]은 체계적 문헌고찰을 통해 위산분비억제제를 복용하게 되면 장내 감염의 위험도가 증가하고(OR 2.55; 95% CI, 1.53-4.26), 장내 감염과의 연관성은 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제(OR 2.03; 95% CI, 1.05-3.92)에 비해 프로톤펌프억제제(OR 3.33; 95% CI, 1.84-6.02)가 높다고 하였다. 이런 위장관 감염의 원인균은 대부분 산도에 약한 세균인 Salmonella와 Campylobacter 등이며[11], 여러 연구 결과에 따르면 위산분비 억제요법과 Salmonella 감염 사이의 위험도(OR)는 2.6-11.2였고[61-65], 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 환자들에서 Campylobacter 감염의 위험도는 1.7-11.7이었다[63,65,66].

Clostridium difficile 장염

C. difficile의 포자형태(spores)의 경우에는 상대적으로 위산에 강하지만, 증식형태(vegetative cells)의 경우에는 매우 취약하다[67]. 이에 이론적으로는 위산이 감소되게 되면, C. difficile의 감염이 증가할 것으로 생각할 수 있다. 하지만 C. difficile의 전파에 가장 중요한 형태는 포자형태이기 때문에 위산분비억제제와 C. difficile 장염 사이의 연관성에 대해서는 아직 명확한 기전을 알 수 없는 상태이다. 프로톤펌프억제제의 사용이 C. difficle 장염의 발생을 증가시킨다는 몇몇 보고들이 있는데, 입원 환자 중에서 2개월 이내 프로톤펌프억제제 사용병력이 있는 환자에서 C. difficile 연관 설사가 2.5배 더 많이 발생하였다(OR 2.5; 95% CI, 1.5-4.2) [68]. 또한 대규모의 지역사회 주민을 대상으로 한 환자-대조군 연구에서 현재 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용하는 환자에서 C. difficile 연관 설사의 위험도가 2.9배로 높았다[69]. 최근의 체계적 문헌고찰에 따르면 위산분비 억제요법이 C. difficile 감염을 증가시키고(OR 1.94; 95% CI, 1.37-2.75), 그 연관성은 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용하였을 경우(OR 1.96; 95% CI, 1.28-3.00)가 히스타민 2 수용체 차단제의 경우(OR 1.40; 95% CI, 0.85-2.29)보다 높았다[60]. 마지막으로, 입원 환자 94명을 대상으로 한 후향적, 환자-대조군 연구에서도 프로톤펌프억제제를 사용한 경우 C. difficle 감염이 증가되었다(OR 3.6; 95% CI, 1.7-8.3) [70].

결 론

장기적인 프로톤펌프억제제의 사용이 증가하면서 최근 부작용에 대한 보고가 빈번해지고 있다. 장기적인 프로톤펌프억제제 사용으로 인해 지속적으로 위산분비가 억제되어 비타민 B12, 철분, 마그네슘, 칼슘 등의 흡수장애가 발생할 수 있으며, 비타민 B12와 칼슘 대사이상으로 인해 골절의 위험도가 커지고, 호흡기 감염과 장내 감염에 대한 감수성이 증가할 수 있다. 이에 모든 위산분비억제제의 사용에 적용되겠지만, 프로톤펌프억제제는 정확한 적응증(소화성 궤양, 출혈성 궤양, 위식도역류질환, Helicobacter pylori 제균 치료 등)에서만 사용하고, 적절한 증상완화 수준을 미리 결정하여 장기적인 혹은 고용량 사용에 따른 부작용 발생을 최소화하려는 노력이 필요하다. 또한, 현재까지 프로톤펌프억제제의 부작용에 대한 연구는 대부분 교란변수 등에 취약한 관찰 연구이거나 소규모의 연구이므로 향후 그 신뢰도를 높일 수 있는 많은 연구들이 필요하다.