만성 B형간염 치료의 최신 지견: 2018 대한간학회 진료 가이드라인을 중심으로

Updated Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B

Article information

Trans Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea. The prevalence of HBV infection is gradually decreasing in Korea, but 3.0% of the total population still suffers from HBV- related chronic liver diseases. In this review, we summarize the updated clinical practice guideline for management of chronic hepatitis B, as revised by the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver in 2018.

서 론

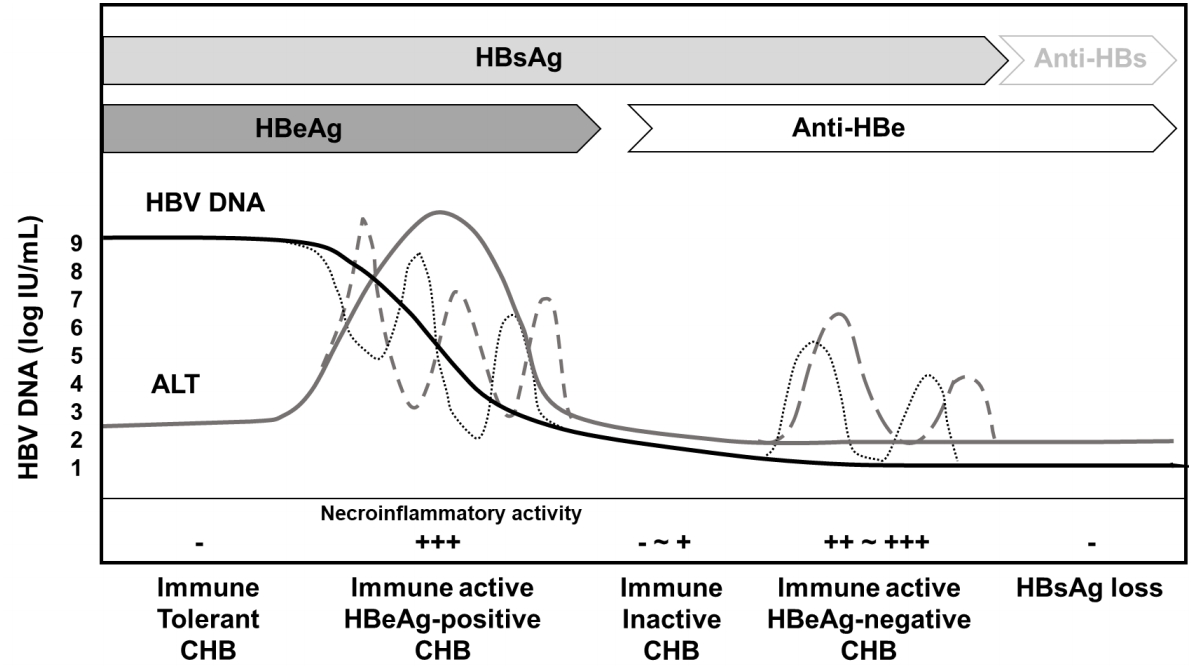

B형간염은 전 세계적으로 3억 5천만 명의 만성 감염자가 있고 매년 60만 명 이상이 관련 질환으로 사망하는 중요한 질환이다[1]. 우리나라에서는 1980년대에는 B형간염 바이러스(hepatitis B virus, HBV) 감염률이 8-10%의 높은 수준으로 국민 보건의 중요한 질환으로 인식되어 1991년 신생아 예방접종 사업, 1995년 국가 예방접종 사업, 2002년 주산기 감염예방사업이 시작되면서 HBV 감염률은 점차 감소하였다. 그럼에도 불구하고 2008년 이후에는 꾸준히 3.0% 수준을 유지하고 있다. 특히 우리나라 만성 간염 및 간경변증 환자의 약 70% [2], 간세포암종 환자의 약 65-75%에서 hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)이 검출되는 점을 고려하면[3], 아직도 만성 B형간염이 우리나라 국민 건강에 미치는 영향은 매우 크다. 만성 B형간염은 감염 후 면역학적 자연경과에서 다양한 소견으로 나타나기에 단 1회의 검사를 통하여 해당되는 임상 단계를 단정짓거나 항바이러스 치료 시작을 결정하는 것이 부적절한 경우가 많다(Fig. 1) [4]. 특히 다른 바이러스에 의한 중복감염, 음주력, 약물 복용력 및 HBV 감염과 간세포암종의 가족력 등에 중점을 둔 병력 청취와 신체 검사가 매우 중요하기에 임상의는 B형간염 치료에 대하여 충분히 숙지하고 진료에 임해야 한다. 본고에서는 2018년 개정된 대한간학회 진료 가이드라인[5]을 중심으로 치료의 목적과 대상, 치료 약제, 약제 내성과 그에 대한 치료 전략에 대하여 기술하겠으며 그간 축적된 연구들을 바탕으로 특정 상황에서의 치료 중 특히 간세포암종 환자, 신기능 이상 또는 골대사 질환자, 면역억제제 또는 항암화학요법 치료 환자, 임산부 또는 임신을 준비 중인 환자의 치료에 대해서 간략하게 소개하고자 한다.

The natural course of chronic hepatitis B. Reproduced from reference [5] with permission. HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; CHB, chronic hepatitis B.

본 론

치료 목적 및 목표

만성 B형간염의 궁극적인 치료 목적은 HBV 증식을 억제하여 염증을 완화시키고 섬유화를 방지하여 간경변증과 간세포암종의 발생을 예방함으로써 간 질환에 의한 사망률을 낮추고 생존율을 향상시키는 것에 있다[6-12]. 그러나 현재까지의 항바이러스 치료제는 치료에도 불구하고 핵내의 covalently closed circular DNA가 지속되기 때문에 HBV의 완전 퇴치를 기대하기가 어려우므로 바이러스 반응을 장기간 유지하는 것이 중요하다[13]. 이와 같이 치료 목적을 달성하기 위한 임상에서의 목표는 ALT의 정상화, 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) 혈청소실 및 전환, HBsAg 혈청소실 및 전환이다. 특히 HBsAg 혈청소실 및 전환은 B형 간염 치료의 이상적인 목표이다.

치료 대상

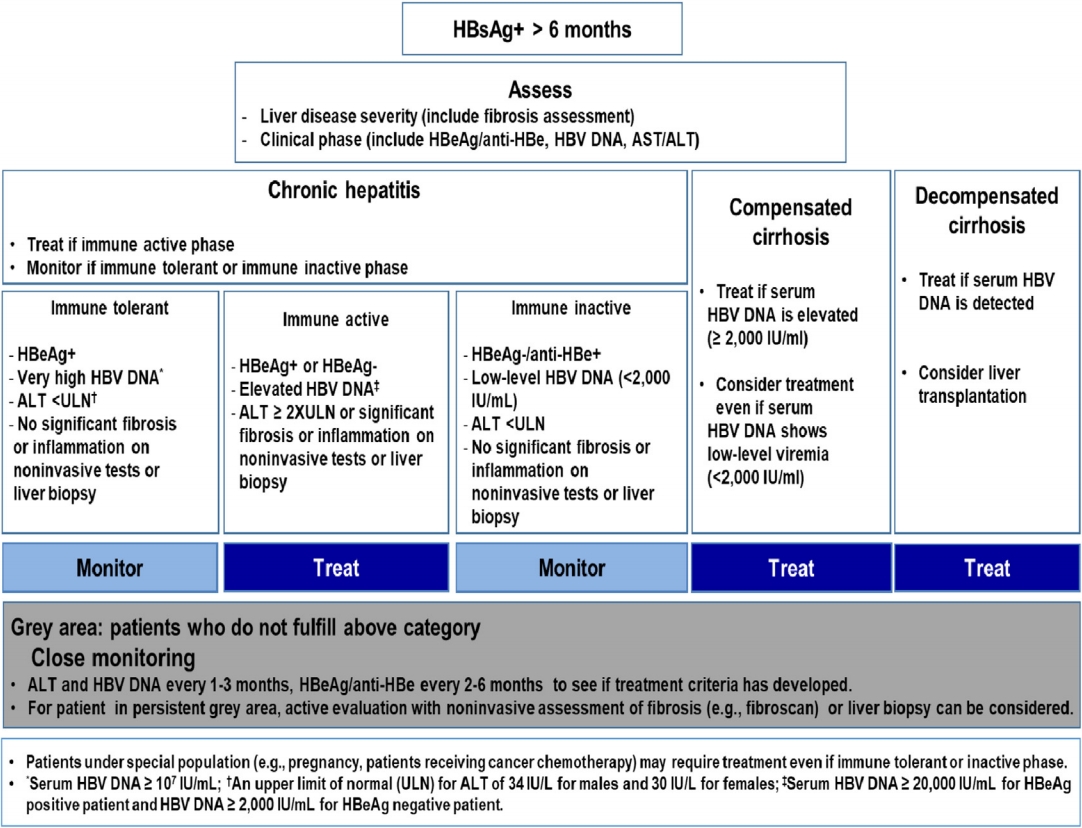

항바이러스 치료 시작을 결정하는 데에는 크게 1) 간 질환의 진행 정도, 2) HBV의 증식 정도, 3) 간손상의 동반 여부와 같은 요소들을 고려한다(Fig. 2). 간 질환의 진행 정도는 대상성 또는 비대상성 간경변증 여부를 판단하여야 하며 HBV의 증식 정도는 혈청 HBV DNA polymerase chain reaction 검사를 통하여 확인할 수 있다. 간손상의 동반 여부는 혈청 ALT가 주로 활용되며, 그 외에도 간생검을 통해서 염증 괴사 동반 여부를 확인할 수 있다.

Algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Reproduced from reference [5] with permission. HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus, ULN, upper limit of normal.

면역관용기

면역관용기는 HBeAg 양성이고, 혈청 HBV DNA값이 대개 107 IU/mL 이상으로 매우 높지만 ALT가 지속적으로 정상 범위를 보이는 특징을 보이며, 간조직 소견에서 염증이 없거나 매우 경미하고 섬유화도 없는 상태이다(Table 1). 이 시기에는 치료 없이 경과를 관찰하여도 예후가 양호하다[14-16]. 이 경우 항바이러스제의 치료 대상이 되지 않는다. 그러나 진료 현장에서는 간생검 시행이 제한적이므로 임상적인 소견만을 조합하여 면역관용기로 추정하여 경과 관찰하는 경우 간세포암종 및 간경변증 합병증이 발생할 수 있는 상당수의 환자가 포함될 수 있어 주의를 요한다[17]. 따라서 연령이 30-40세 이상이거나, 혈청 HBV DNA < 107 IU/mL이거나, 비침습적 검사에서 임상적으로 유의한 간섬유화를 시사하는 소견이 있거나, ALT가 정상 상한치의 경계에 있는 경우에는 간생검을 시행하여 치료 여부를 결정할 수 있다.

면역활동기

만성 B형간염 환자 중 바이러스의 활동적 증식과 함께 중등도 이상의 염증과 2단계 이상의 의미 있는 섬유화를 보이는 경우 면역활동기로 평가한다. 면역활동기의 경우 메타분석에서 항바이러스 치료는 간경변증의 위험, 비대상성 간경변증의 위험, 간세포암종의 위험을 낮추는 것이 확인되어[18], 항바이러스 치료의 대상이 된다. 바이러스의 활동적 증식은 HBeAg 양성의 경우에는 2,000-20,000 IU/mL 이상, HBeAg 음성의 경우에는 2,000 IU/mL 이상인 경우로 정의한다. 간의 염증과 섬유화 소견은 간생검을 통하여 확인할 수 있으나 간생검의 침습적인 특징으로 널리 활용하기 어려워 혈청 ALT를 간손상을 반영하는 간편한 지표로 활용하고 있다. 그러나 ALT의 증가 정도와 조직학적인 간손상의 정도는 항상 일치하는 것이 아니며 음주, 약물, 지방간 등 다른 원인에 의한 ALT 상승일 수도 있음을 유의해야 한다. 다른 원인에 의한 ALT 상승이 아니라면 ALT가 정상 상한치의 두 배 이상으로 상승한 경우 B형간염의 항바이러스 치료를 시작한다. 혈청 ALT가 정상 상한치 이내인 경우에 비하여 정상 상한치보다 약간 상승한 경우 간경변증 및 간세포암종의 발생 위험이 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있고[19,20], ALT의 정상 상한치에 대해서는 연구마다 다양하게 보고되고 있어[21-23] ALT가 정상 상한치의 1-2배인 경우 치료를 시작해야 하는지 판단할 수 있는 근거가 부족하다. 다만 지속적으로 정상 상한치의 1-2배인 경우에는 집중 모니터링을 하고, 간섬유화 정도를 비침습적으로 확인하거나 간생검을 시행하여 치료 여부를 결정할 수 있다. 국내 만성 HBV 보유자 1만 2천여 명을 대상으로 분석한 연구에서 간 질환 관련 사망률을 예측할 수 있는 한계치로 남성은 34 IU/L, 여성은 30 IU/L를 제시한 바 있다[24]. 이는 후향 연구이지만 다양한 연령군의 국내 환자들을 분석한 결과이며 경한 지방간 질환이 배제되지 않아 현실적인 수치를 반영함과 동시에 간 질환 관련 예후 예측이라는 실질적인 요구를 반영한 자료로서 향후 전향적인 검토가 이루어질 때까지 만성 B형간염 환자에서의 정상 상한치로 수용하는 것이 타당할 것이라고 판단된다.

면역비활동기

면역비활동기는 HBeAg 음성, anti-HBe 양성, 지속적인 정상 ALT, 그리고 HBV DNA가 불검출되거나, 낮은 농도(< 2,000 IU/mL)로 지속되는 시기이다. 진행된 간섬유화의 증거가 없는 경우 치료 없이 경과 관찰하여도 좋은 예후를 보이는 반면[25], 진행된 간섬유화가 동반된 경우에는 간세포암종 등 합병증 발생 위험이 증가하는 것으로 보고되고 있다[26]. 따라서 면역비활동기는 치료 대상이 되지 않지만 간섬유화 정도에 대한 평가가 필요하며, 혈청 ALT, HBV DNA 등을 정기적으로 검사하여 HBeAg 음성 간염 및 HBeAg 양성 간염으로 재활성화가 되지 않는지 지속적으로 관찰하고 감시해야 한다.

대상성 간경변증

메타분석을 포함한 여러 연구에서 항바이러스 치료는 대상성 간경변증 환자에서 간 질환의 진행과 간세포암종 발생 위험을 낮출 수 있는 것이 확인되었으며[18], 간경변증이 동반된 경우에는 ALT가 높지 않은 경우가 흔하여, 혈청 HBV DNA ≥ 2,000 IU/mL인 대상성 간경변증의 경우에는 ALT에 관계없이 항바이러스 치료를 시작한다. 혈청 HBV DNA < 2,000 IU/mL로 낮은 혈청 HBV DNA 농도를 보이는 대상성 간경변증 환자인 경우 높은 근거 수준의 연구는 없으나 항바이러스 치료를 하여 HBV DNA 불검출을 유지한 경우에 비하여 낮은 농도의 바이러스라도 간세포암종의 발생[27], 사망 및 간 관련 합병증 위험도 높았다고 보고되어[28], ALT에 관계없이 항바이러스 치료를 고려한다.

비대상성 간경변증

비대상성 간경변증 환자들은 HBV의 재활성화 시에 간부전 위험이 매우 높으며 경구용 항바이러스제 사용은 간기능을 개선시키고 이식의 필요성을 경감시키며 자연경과를 개선시킨다[11,29]. 따라서 비대상성 간경변증의 경우 바이러스 증식의 정도에 무관하게 혈청 HBV DNA가 검출되면, ALT와 관계없이 경구용 항바이러스제 치료를 시작한다. 항바이러스제를 투여하더라도 바이러스 반응을 획득하고 임상적으로 회복을 보이는 데까지는 시간이 필요하므로, 항바이러스제 투여에도 불구하고 간부전 증상이 진행되는 경우에는 간이식을 고려해야 한다[30].

치료 약제

2017년부터 국내에서 테노포비어 알라페나마이드 푸마르산(tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, 이하 테노포비어 AF)과 베시포비어 디피복실 말레산(besifovir dipivoxil maleate, 이하 베시포비어)이 성인에서 만성 B형간염 치료제로 승인됨에 따라 총 8가지의 항바이러스제를 사용할 수 있다. 약제들은 크게 주사용 항바이러스제인 페그인터페론 알파와 경구용 항바이러스제로 나눌 수 있으며 경구용 항바이러스제는 내성 발현의 유전자 장벽에 따라 크게 두 부류로 나뉜다. 엔테카비어, 테노포비어 DF, 테노포비어 AF, 베시포비어는 유전자 장벽이 높아 HBeAg 양성 및 음성 만성 B형간염 환자의 1차 치료 약제로 권고된다. 특히 엔테카비어와 테노포비어 DF는 효과와 장기간의 안전성이 검증되었으나 테노포비어 AF와 베시포비어는 장기 추적 데이터가 조금 더 필요하다.

테노포비어 AF

테노포비어 AF는 생체에서 이용되는 테노포비어의 전구약제로, 테노포비어 DF보다 혈장에서 더 안정적이고 반감기가 길어, 테노포비어 DF보다 더 적은 용량으로 유사한 항바이러스 효과를 나타내면서 전신 노출을 감소시켜, 결과적으로 신장과 골대사에 대한 독성을 감소시킨다. 테노포비어 AF는 HBeAg 양성 환자군에서 96주 치료 관찰시 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출률 73%, HBeAg 혈청소실률 22%, HBsAg 혈청소실률 1%로 테노포비어 DF군과 유사한 결과를 보였다. 96주의 ALT 정상화율은 테노포비어 AF군이 더 높은 정상화율을 보였다[31]. HBeAg 음성 환자군에서 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출률은 90%였으며 HBsAg 혈청 소실은 1% 미만으로 테노포비어 DF군과 유사하였으며 ALT 정상화율은 테노포비어 AF군이 더 높았다[31]. 앞서 언급한 임상 연구에서 간경변증 환자는 HBeAg 양성 만성 B형간염 환자 중 7.4% [32], HBeAg 음성 만성 B형간염 환자 중 9.8% [33]에서 포함되어 있었으나 하위분석을 시행하지는 않았으며 비대상성 간경변증 환자는 연구에서 제외되어 아직 결과가 보고된 바는 없다. 테노포비어 AF는 테노포비어 DF와 동일한 유전자 장벽을 보일 것으로 기대하나[4,34], 향후 임상자료의 축적이 필요하다. 만성 신부전이 동반되었거나 낮은 사구체 여과율을 보이는 환자, 골감소/골다공증을 보이는 고령 환자에서는 테노포비어 DF의 사용은 신중해야 하며 같은 경우에 있어 치료제를 결정할 때에는 엔테카비어 또는 테노포비어 AF가 추천된다.

베시포비어

베시포비어는 뉴클레오티드 유사체로서 3상 다기관 임상 연구에서 베시포비어 96주 투여시 HBeAg 양성 환자의 경우 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출률 81.1%, 혈청 ALT 정상화율 64.2%, HBeAg 혈청전환률 7.7%였으며 HBeAg 음성 환자의 경우 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출률 97.0%, 혈청 ALT 정상화율 87.9%였다. HBsAg 혈청소실은 모두 관찰되지 않았다[35]. 대상성 간경변증 환자의 결과는 제한적이며, 비대상성 간경변증 환자는 포함되어 있지 않으므로 추가적인 연구가 필요하다. 베시포비어-베시포비어 치료(86명)와 테노포비어 DF-베시포비어(84명) 교체 투약을 총 96주 동안 지속한 공개군 연장 연구에서 베시포비어-베시포비어군에서는 2명(2.3%), 테노포비어 DF-베시포비어군에서는 11명(13.1%)에서 바이러스 돌파 현상이 관찰되었지만 모든 환자에서 내성 변이는 관찰되지 않았다[35]. 베시포비어 2상 임상시험 중 가장 흔히 보고된 부작용은 L-카르니틴의 감소로 하루 660 mg씩 L-카르니틴 보충제를 투약한 경우 2년 임상시험 종료까지 혈청 L-카르니틴의 농도는 정상적으로 유지되었으며 결핍으로 인한 합병증은 관찰되지 않았다[36,37].

항바이러스 내성

HBV의 경구용 항바이러스제로 사용되는 핵산유사체는 크게 L-뉴클레오시드 유사체 계열(라미부딘, 텔비부딘, 클레부딘)과 cylopentane 계열(엔테카비어), 뉴클레오티드 유사체인 acyclic phosphonate 계열(아데포비어, 테노포비어, 베시포비어)로 분류할 수 있다[38]. 테노포비어 DF의 경우 과거에 rtA194T가 rtL180M + rtM204V와 같이 발생할 경우 6.9-10배 이상 테노포비어에 대한 감수성이 감소하는 것으로 보고되었다[39-41]. 최근 국내에서는 rtS106C + rtH126Y + rtD134E + rtL269I일 경우 테노포비어에 대한 저항성이 15.3배 증가함을 확인하였다[42]. 베시포비어의 경우 다기관 임상 연구에서 약제 순응도가 떨어진 환자에서 바이러스 돌파 현상이 관찰되었지만 내성과 관련된 바이러스 변이는 관찰되지 않았다[37,43].

약제 내성의 치료

라미부딘, 텔비부딘, 클레부딘, 엔테카비어 등 뉴클레오시드 계열의 약제 내성에 대해서는 테노포비어 단독 치료로 변경하는 것이 가능하다[44-46]. 하지만 내성 치료 전 고바이러스혈증(HBV DNA > 4 log)에서는 테노포비어 DF/엔테카비어 병합요법이 테노포비어 DF 단독요법에 비하여 바이러스 반응이 더 우월하였다[45].

뉴클레오티드 계열인 아데포비어 내성 만성 B형간염에 대해서 테노포비어 단독 치료로 전환하거나 테노포비어/엔테카비어 병합 치료로 전환을 추천한다. 최근 국내 전향적 무작위 연구에서 아데포비어 내성이 확인된 경우 테노포비어 DF 단독 치료와 테노포비어 DF/엔테카비어 병합 치료에서 유사한 치료 효과를 보였다[47]. 이들 환자를 3년간 추적관찰하였을 때 약제 조합 간 혈청 HBV DNA 불검출률에서는 차이가 없으나 소그룹 분석에서 rtN236T와 rtA181T/V 변이를 동시에 가지고 있는 경우가 단독 변이를 가지고 있는 경우보다 바이러스 반응이 의미 있게 낮아 추후 이에 대한 장기간 추적 연구가 필요하다[48]. 따라서 이전에 아데포비어에 노출력이 있거나 내성이 발생한 환자에서 테노포비어 단독 치료를 할 경우 면밀한 모니터링이 필요하다.

뉴클레오시드/뉴클레오티드 계열의 두 가지 이상의 약제에 대한 내성변이를 경험한 다약제 내성의 경우 테노포비어/엔테카비어 병합 치료 또는 테노포비어 단독 치료로 전환한다. 하지만 최근 국내에서 테노포비어 내성 환자가 보고된 점[42]과 다약제 내성을 보이는 환자에서 약 1/4의 환자에서는 치료 3년째까지 바이러스 반응에 도달하지 못하였던 점[48], 특히 아데포비어 내성 환자에서는 그 효과가 감소하는 점 등에서 다약제 내성을 보이는 환자에서 테노포비어 단독 치료가 가지는 장기간 효과에 대하여 검증이 필요하다.

간세포암종 환자

HBV 양성 간세포암종 환자에서 항바이러스 치료는 우선적으로 HBV 증식을 억제하여 간 질환의 진행을 막고 간세포암종에 대한 적극적인 치료를 가능하게 하기 위함이며, 또한 근치적 치료를 받은 환자라면 간세포암종의 재발 위험을 줄이기 위함이다. 수술적 절제 후 항바이러스제를 사용한 경우 간세포암종의 재발 위험성을 줄이고(hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% 신뢰구간, 0.32-0.70), 간세포암종 관련 사망의 위험성도 줄였다(HR, 0.26; 95% 신뢰구간, 0.14-0.50) [49]. 혈청 HBV DNA가 2,000 IU/mL 이하로 상대적으로 낮은 환자들을 대상으로 한 무작위 배정 연구에서도 항바이러스 치료가 근치적 수술 후 무재발 생존 기간과 총 생존 기간을 유의하게 증가시키는 것으로 보고되었다[50]. 고주파열치료술 또는 수술적 치료와 같은 근치적 치료가 아니더라도 경동맥화학색전술의 경우 약 4-40% [51,52], 간동맥주입 화학요법 후 24-67% [53], 세포독성 화학요법 후 30-60% [53,54], 체외 방사선 치료 후 ~22% [55], 소라페닙 사용 후 0-36% [56]의 다양한 재활성화가 보고되므로 B형간염 관련 간세포암종 환자에서 혈청 HBV DNA가 불검출이더라도 간세포암종 치료 시에는 경구용 항바이러스제를 이용한 예방적 항바이러스 치료를 고려한다. 한편 니볼루맙, 펨브롤리주맙 등 면역관문억제제는 그 자체가 체내 면역력을 증가시키는 역할을 하므로 역으로 HBV에 대한 면역 반응을 증가시켜 심한 급성 악화를 보일 수 있다. 따라서 면역관문억제제를 사용하기 전에 항바이러스제를 사용하여 HBV의 증식을 억제해 놓을 필요가 있다[57].

신기능 이상 또는 골대사 질환자의 치료

B형간염 치료 약제 자체가 신기능이나 골밀도에 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로 신기능 감소가 있거나 골대사 질환 또는 골대사 질환의 위험이 있는 경우 초치료 경구용 항바이러스제를 결정할 때 테노포비어 DF보다는 엔테카비어, 테노포비어 AF [31-33,58,59], 베시포비어[36]가 우선 추천된다. 테노포비어 DF를 복용하고 있는 환자에서 신기능 감소나 골밀도의 감소를 보이거나 또는 그 위험성이 있는 경우 치료 기왕력에 따라 테노포비어 AF [31-33,58], 베시포비어[35] 또는 엔테카비어로 전환할 수 있다. 모든 약제는 크레아티닌 청소율에 따라 적절히 용량을 조절해야 하며, 테노포비어 AF는 크레아티닌 청소율 15 mL/min 미만인 경우, 베시포비어는 크레아티닌 청소율 50 mL/min 미만인 경우, 테노포비어 DF는 크레아티닌 청소율 10 mL/min 미만이면서 신대체요법을 시행하지 않는 경우 추천되지 않는다.

면역억제제 또는 항암화학요법 치료 환자의 치료

만성 B형간염의 경과는 면역억제 치료 혹은 항암화학요법 등에 의하여 면역능이 저해될 경우 재활성화의 위험이 증가한다[60]. 만성 B형간염의 재활성화는 만성 B형간염의 악화(exacerbation of chronic HBV infection)와 HBsAg 음성이면서 antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) 양성인 경우인 과거 B형간염의 재발(relapse of past HBV infection) 두 가지 상황으로 나눌 수 있다. 만성 B형간염의 악화는 HBsAg 양성이면서 혈청 HBV DNA가 기저치에 비하여 100배 이상 증가하는 경우로 정의하고, 과거 B형간염의 재발은 HBsAg 음성에서 양성으로 나타나거나, 혈청 HBV DNA가 불검출에서 검출로 나타나는 경우로 정의한다. 혈청 ALT 수치가 기저 수치에 비하여 3배 이상 혹은 100 IU/L 이상 증가하는 경우를 활동성 간염으로 정의한다[61,62]. 2018년 개정된 대한 간학회의 만성 B형간염 가이드라인에서는 B형간염 재활성의 위험도를 고위험군(10% 이상), 중간위험군(1-10%), 혹은 저위험군(1% 미만)으로 분류하고 이에 따른 치료 전략을 제시하고 있다[57,63]. 일단 B형간염이 재활성화될 경우 간부전 및 사망의 위험까지 있으므로 예방을 위하여 HBV 감염 여부가 확인되지 않은 경우 면역억제/항암화학요법을 시작하기 전에 HBsAg 및 anti-HBc를 검사하고, 둘 중 하나 이상 양성인 경우 혈청 HBV DNA를 검사한다. HBsAg 양성이거나 HBV DNA가 검출되는 경우 면역억제/항암화학요법 시행과 함께 혹은 시행 전에 예방적 항바이러스 치료를 시작한다. 항바이러스제는 혈청 HBV DNA, 면역억제/항암화학요법의 강도 및 기간, 경제적 측면 등을 종합적으로 고려하여 선택하되, 초기 혈청 HBV DNA가 높거나 장기간 치료가 예상될 경우 테노포비어 또는 엔테카비어를 우선적으로 사용한다[64]. HBsAg 음성 및 HBV DNA 불검출이고 anti-HBc가 양성인 경우 고위험군에서는 면역억제/항암화학요법 치료 중에 혈청 HBsAg와 HBV DNA를 모니터링하며, HBV 재활성화가 발생할 경우 항바이러스 치료를 시행한다. 특히 리툭시맙을 사용하는 경우에는 약제 투여와 동시에 항바이러스 치료를 시작할 수 있다. 예방적 항바이러스제 종료는 면역억제/항암화학요법 종료 후 최소 6개월간 지속하고[65], 리툭시맙을 사용하는 경우 치료 종료 후 최소 12개월간 사용한다[66,67]. 예방적 항바이러스 치료 중 및 치료 후 혈청 HBV DNA를 정기적으로 모니터링한다.

임산부 또는 임신을 준비 중인 환자에서 치료

일반적으로 임신 기간 중에는 호르몬 변화 또는 면역학적 변화에 의하여 면역관용기에 해당하는 경우가 많다[68,69]. 그러나 임신 후반기와 출산 후에는 모체 면역 반응이 원상복귀되면서 혈청 HBV DNA 감소와 ALT 상승으로 이어질 수 있어 이 기간 중 주의 깊은 관찰이 필요하다[70,71]. 임산부 또는 임신을 준비 중인 환자에서 경구용 항바이러스제의 투약은 일반적인 치료 원칙에 기반하되 임산부와 태아에게 미칠 수 있는 장단기적 영향을 고려하여 신중하게 결정해야 하며 약제 중 테노포비어 DF를 권장한다[72,73]. 테노포비어 AF는 아직 연구 결과가 더 필요하다. 페그인터페론 알파는 치료 기간 중 임신은 금기이며 임산부에서도 사용하지 않아야 한다. 테노포비어 DF 이외의 경구용 항바이러스제 복용중 임신 사실을 알게 되었을 경우에는 임산부와 태아에 비교적 안전한 테노포비어 DF로 변경을 권장하며[74,75], 출산 후 모유 수유시에도 약제의 사용을 제한하지 않는다[76-79]. 항바이러스 치료를 받지 않는 만성 B형간염 임산부에서 출산 후 모유 수유는 제한하지 않는다[80]. 혈청 HBV DNA가 200,000 IU/mL 이상인 임산부의 경우 태아의 수직감염을 예방하기 위하여 테노포비어 DF 투여가 권장된다[81,82]. 시기는 임신 24-32주에 시작하여 출산 이후 2-12주까지 투여가 권장된다.

결 론

대한간학회에서는 그간 국내외로 축적된 연구 결과를 반영하고 새로이 사용 가능하게 된 만성 B형간염 항바이러스제의 정보를 추가하여 2018년 만성 B형간염 가이드라인을 개정하여 최신 지침을 정리하여 제시하였다. 다만 환자 진료에서 최선의 선택은 경우에 따라 다를 수 있으므로 치료는 제반 상황을 고려하여 개별화되어야 한다.

Acknowledgements

가이드라인 개정에 힘을 아끼지 않으신 대한간학회 이사회 및 개정위원회, 자문위원회 선생님들께 깊은 감사의 뜻을 전합니다.