2018 대한부정맥학회 NOAC 사용 지침: 특별한 상황에서의 약물 복용(관상동맥질환, 용량 혼동시, 심율동 전환, 뇌졸중 발생, 악성종양) 및 기타

2018 Korean Heart Rhythm Society Guidelines for Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants

Article information

Trans Abstract

Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are an alternative to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and have emerged as the treatment of choice in Korea. However, several questions remain regarding the optimal use of these agents in specific clinical situations. In this paper we discuss 1) patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and coronary artery disease, 2) avoiding confusion with NOAC dosing across indications, 3) cardioversion in a patient treated with a NOAC, 4) AF patients who present with acute stroke while on NOACs, 5) NOACs in special situations, 6) anticoagulation in AF patients with a malignancy, and 7) optimizing VKA dose adjustments.

서 론

심방세동 환자에서 혈전색전증을 예방하기 위해서는 항응고 치료가 필수적이다. 비-비타민 K 길항 항응고제(non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, NOAC)는 비타민 K 길항제를 대신하여 사용할 수 있으며 한국에서 우선시되는 약제로 대두되었다. 최근에는 임상 진료시 의사와 환자 모두 NOAC에 많이 익숙해졌다. 하지만 특별한 임상 상황에서 이 약제의 적절한 사용에 대하여 해결되지 않는 경우들이 있다. 대한부정맥학회는 특별한 임상 상황에서의 NOAC의 처방에 대한 적절한 진료 지침을 제시하고자 한다.

본 론

관상동맥질환이 동반된 심방세동 환자

관상동맥질환과 심방세동이 같이 있는 경우는 항혈소판 약제와 항응고제(NOAC 혹은 와파린)를 사용해야 하는 복잡한 임상 상황으로 높은 유병률과 사망률이 관련되어 있다[1,2]. 경구용 항응고제에 아스피린 또는 P2Y12 억제제를 추가하는 것을 ‘2제 요법’으로 정의하고, 아스피린과 P2Y12 억제제를 모두 추가하는 것을 ‘3제 요법’으로 정의한다. 경구용 항응고제에 아스피린이나 P2Y12 억제제와 같은 항혈소판약제를 추가하는 것은 불가피하게 출혈의 위험성을 증가시키므로[3-6] 장기간의 3제 요법은 피해야 한다[7-9].

아스피린과 P2Y12 억제제 동시 투약은 스텐트 혈전증을 예방하기 위하여 필요하나[10] 뇌줄중 예방에는 충분하지 않으며, 반대로 항응고제는 뇌졸중 예방에 필요하나 새로운 관상동맥 사건을 예방하기에는 적당하지 않다[11]. 최근 심방세동[11], ST분절 상승 심근경색[12], 항혈소판약제 사용[13]의 유럽학회 지침에 따르면 급성 심장 사건 또는 경피적 관상동맥 스텐트 삽입술을 한 이후 12개월까지 경구용 항응고제에 적어도 하나 이상의 항혈소판약제 추가가 권고되고 있다.

지금까지 경피적 관상동맥 시술 후 경구용 항응고제의 사용에 대한 전향적 연구들은 많지 않다. 최근 무작위 임상연구들에서 경피적 관상동맥 시술 후 3제 요법(경구용 항응고제, 아스피린, P2Y12 억제제)에 비하여 2제 요법(아스피린 또는 P2Y12 억제제와 경구용 항응고제)으로 치료한 심방세동 환자들에서 출혈의 위험성이 50% 정도 감소하였다[14]. 또한 진행 중인 2개의 연구인 apixaban versus vitamin K antagonist in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome and/or percutaneous coronary intervention (AUGUSTUS)과 edoxaban treatment versus vitamin K antagonist in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (ENTRUST-AF PCI) [15]에서 3제 요법을 어떻게 얼마나 오래 사용할 것인지에 더 많은 정보를 제공할 것으로 기대한다.

지침에 따르면 경구용 항응고제를 사용 중인 심방세동 환자에서 경피적 관상동맥 시술을 하는 경우 계획된 또는 응급경피적 관상동맥 시술 동안 비타민 K 길항제를 유지하도록 권고하고 있으나, NOAC는 예정된 시술이나 조기 관상동맥조영술의 시행이 예상되는 비-ST분절 상승 관상동맥 증후군에서는 잠시 중단한다. 반면 비침습적으로 치료하는 급성 관상동맥 증후군 환자에서는 지속되어야 한다. NOAC 사용 중에 경피적 관상동맥 시술을 시행할 때는 비타민 K 길항제를 사용하는 경우와 여러 가지 이유로 다르다. 마지막 복용 시기와 복용력을 확인해야 하며, 항응고제 정도의 불확실성, 시술 중 추가적인 항응고제 사용의 불확실성, 신기능의 다양성 등을 고려해야 한다. 2016년 유럽학회 심방세동 지침에서 3제 요법을 위한 ticagrelor 또는 prasugrel의 사용은 권장되지 않고 있다(class Ⅲ, level of evidence C). 그러나 NOAC와 ticagrelor 또는 prasugrel의 2제 요법과 NOAC와 아스피린, clopidogrel의 3제 요법에 대해서는 언급이 없었다[11,16]. 이는 혈전 고위험성, 급성 관상동맥 증후군, 이전의 스텐트 혈전증의 특수한 상황에서는 NOAC와 새로운 P2Y12 억제제들 중 하나와 사용할 수 있는 기회를 남겨두었다. Randomized evaluation of dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran versus triple therapy with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoin percutaneous coronary intervention (REDUAL-PCI) 연구에서 ticagrelor는 2제 요법의 경우 안전하며 효과적이었다[17]. 반면에 새로운 P2Y12 억제제를 포함한 3제 요법은 경피적 관상동맥 시술 첫날을 제외하고는 권장하지 않고 있다.

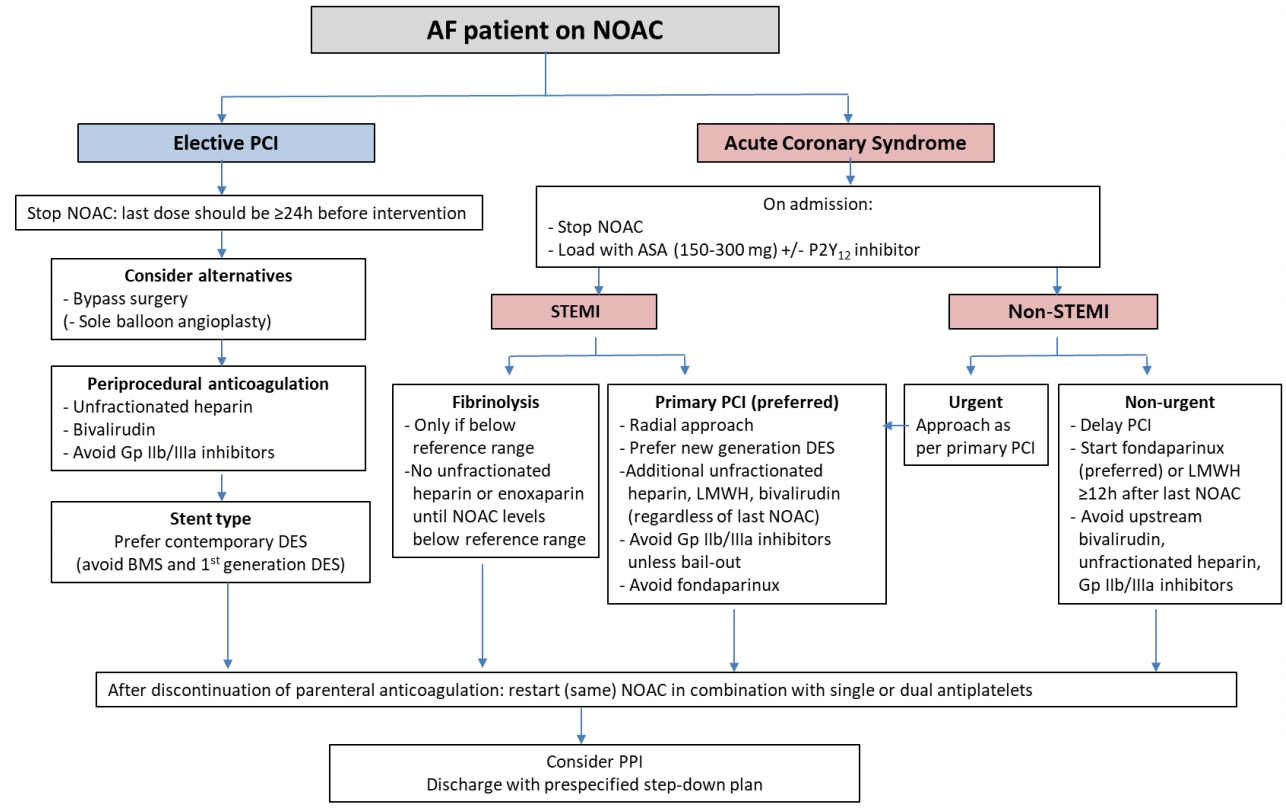

입원 중 치료는 그림 1에서 설명하고 있다. 안정형 협심증 환자에서 계획된 관상동맥 시술을 하는 경우에는 시술 후 2제 또는 3제 요법의 기간을 짧게 하기 위하여 약물 방출 스텐트가 선호된다. 풍선 확장술만 하거나 관상동맥우회로술은 장기간의 2제 또는 3제 요법의 필요성이 줄어들기 때문에 장기적인 항응고제 사용이 필요한 환자에서 치료 전략이 될 수 있다. 계획된 경피적 관상동맥 시술 후 NOAC를 비타민 K 길항제로 바꿀 이유는 없으며 NOAC를 다시 시작하는 것과 비교하여 출혈과 혈전색전증의 위험성을 증가시킬 수 있다. NOAC는 시술 전에 중지되어야 하며 시술은 적어도 마지막 복용 후 12-24시간에 시행되어야 한다. 시술 중 항응고제는 사용되어야 하는데 enoxaparin보다는 비분획 헤파린(70 IU/kg)이 선호된다[18]. 급성 관상동맥 증후군 환자의 경우에는 금기증이 없다면 NOAC를 복용 중인 모든 환자는 P2Y12 억제제와 아스피린(150-300 mg 추가 용량)을 복용해야 한다. 새로운 P2Y12 억제제는 불안정형 환자에서 최대 항혈전 효과에 이르는 데 시간이 걸리므로 아스피린이 없는 P2Y12 억제는 급성 상황에서는 권고되지 않는다. ST분절 상승 심근경색 환자의 경우에는 요골동맥을 통한 일차 경피적 관상동맥시술이 혈전용해제보다 강력히 권고된다. 마지막 NOAC의 복용시간에 관계 없이 추가적인 정맥용 항응고제 사용이 권고된다[19]. 긴급한 상황이 아니라면 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa 억제제 사용은 피해야 한다. 혈전용해제가 유일한 혈류 개통 치료인 경우에도 NOAC의 효과가 감소된 후(마지막 복용 후 12시간 이상 경과)에 사용할 수 있으며 이 경우 추가적인 비분획 헤파린이나 enoxaparin은 사용해서는 안된다. 비-ST분절 상승 심근경색 환자에서는 NOAC를 중지하고 이 효과가 감소되기를 기다려야 하며(마지막 복용 후 12시간 이상 경과) fondaparinux 또는 enoxaparin은 투약할 수 있다. 추가적인 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa 억제제 사용은 피하고 비분획 헤파린은 위급 상황에서만 권고된다(class IIb C) [20]. 출혈 위험성을 줄이기 위하여 요골동맥을 통한 접근이 선호된다[19].

Acute management of elective percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with NOACs. AF, atrial fibrillation; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; h, hours; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare metal stent; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

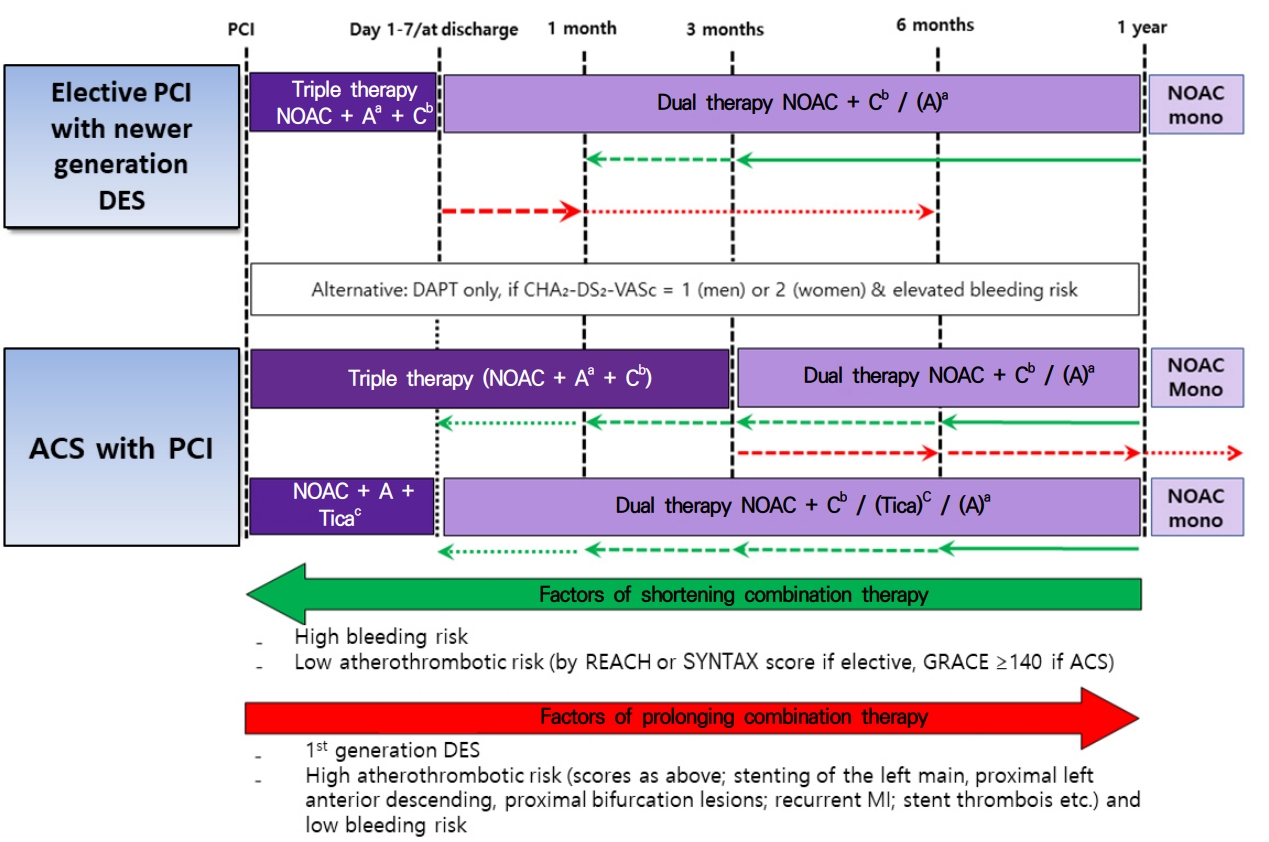

시술 후 안정된 환자에서 정맥용 항응고제가 중지된 후 경구용 항응고제는 즉시 다시 사용되어야 한다. 특히 비타민 K 길항제로의 교체는 이전에 사용한 적이 없어 적절한 용량을 모르는 경우는 출혈과 혈전색전증의 위험성을 증가시킬 수 있으므로 권고되지 않고 있다. 관상동맥우회로술을 시행받은 심방세동 환자도 똑같이 적용된다. NOAC와 항혈소판약제의 초기 복합요법뿐만 아니라 지속적인 아스피린 또는 P2Y12 억제제의 사용은 허혈과 출혈의 위험성에 따라 주의 깊게 접근해야 한다(Fig. 2). RE-DUAL PCI [17]와 an open-label, randomized, controlled, multicenter study exploring two treatment strategies of rivaroxaban and a dose-adjusted oral vitamin K antagonist treatment strategy in subjects with atrial fibrillation who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PIONEER AF-PCI) [21] 연구에서 보면 3제 요법은 가능한 짧게 유지해야 하며 급성기 후 1주일 이내에 NOAC와 P2Y12 억제제의 2제 요법으로 사용하는 것이 선택할 수 있는 대안이다. 시술 후 1년 동안 NOAC 또는 비타민 K 길항제와 하나 또는 두 가지의 항혈소판약제의 복합사용은 출혈의 위험성을 증가시킨다[1,3,5,17,21,22]. CHA2DS2-VASc와 global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE) 측도를 이용하여 뇌졸중과 허혈의 위험성을 판단해야 하며[13], 출혈 위험성을 평가하여 교정할 수 있는 출혈 위험인자를 줄이는 노력을 해야 한다[16]. 장기간의 치료를 위한 많은 복합요법들 중에 3제 요법 또는 2제 요법의 기간을 단축시키기 위한 의사의 선택이 필요하다. 양성자 펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor)는 항혈소판약제와 항응고제의 복합요법 특히 3제 요법을 하는 환자에게 권고되어야 한다. 급성 관상동맥 증후군과 같은 허혈성 고위험군 환자에서 3제 요법은 1개월에서 최대 6개월까지 사용하도록 권고되고 있으므로 그후 1년까지는 2제 요법(NOAC와 아스피린 또는 클로피도그렐)으로 바꾸어 사용해야 한다[13]. 경피적 관상동맥 시술 후 6개월 이상 3제 요법을 사용하는 것은 권고되지 않으며 더 짧게 사용해도 충분하다. 3제 요법의 기간을 단축하고 조기에 2제 요법으로 바꾸는 요인은 동맥경화 혈전증의 위험이 낮고, 출혈 위험성이 높은 경우이다. 반대로 시술 또는 구조적 요인으로 인하여 더 장기적인 3제 요법을 시행할 수도 있다. 뇌졸중 위험이 적고(남성에서 CHA2DS2-VASc 0-1 또는 여성에서 CHA2DS2-VASc 1-2인 급성 관상동맥 증후군) 출혈 위험성이 높은 환자를 대상으로 진행된 소규모 연구에서 처음부터 항응고제 없이 2제 요법으로만 치료를 시작할 수 있었다[10]. 시술 1년 후의 만성 관상동맥질환 환자에서는 2016년 심방세동에 대한 유럽학회 지침에서 항혈소판약제를 모두 중지하도록 권고하고 있으며, 단지 관상동맥 사건의 위험성이 아주 높은 경우에서만 항응고제와 하나의 항혈소판약제를 복합하여 사용하도록 권고하고 있다[13,16]. 안정형 협심증의 경우 경피적 관상동맥 시술 후 허혈의 위험성의 낮고, 출혈의 위험성이 높은 경우에 조기(6개월)에 NOAC 단독으로 교체할 수 있다.

Long-term treatment in patients receiving NOAC therapy after elective percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; DES, drug-eluting stent; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; REACH, reduction of atherothrombosis for continued health; SYNTAX, synergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with taxus and cardiac surgerey; GRACE, global registry of acute coronary events. aAspirin 75-100 mg once daily (qd). bClopidogrel 75 mg qd. cTicagrelor 90 mg twice daily (bid).

급성 관상동맥 증후군 후 1년 이내에 새로 발견된 심방세동 환자는 항응고제를 사용하여 혈전색전증을 예방해야 하는 적응증이 되며 항응고제는 즉시 시작되어야 하고 2제 요법을 지속하는 경우 증가되는 출혈의 위험성을 고려해야 한다. 급성 관상동맥 증후군 후 1년 후에 발생한 심방세동 환자는 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수에 따라 항응고제를 복용해야 한다. 항응고제 단독이 아스피린 단독보다 더 효과적이며 항응고제와 아스피린 복합요법은 더 효과적이지 않으며 출혈 위험성을 증가시킨다는 연구에 따라서 안정형협심증이 있는 심방세동 환자에서는 항혈소판약제 없이 항응고제 단독으로 사용해도 충분하다[13,23,24]. 심방세동 환자를 대상으로 진행된 4가지 NOAC의 3상 연구에서 약 1/3의 환자에서 관상동맥질환이 있었고 15-20% 환자에서 이전에 심근경색 병력이 있었다[25-28]. 얼마나 많은 환자에서 얼마나 오랫동안 항혈소판약제를 복용했는지 명확하지 않았음에도 불구하고 이전의 심근경색 병력의 유무와 효과 또는 안전성과는 연관성이 보이지 않았다. 비타민 K 길항제 대비 NOAC의 장점은 관상동맥질환이 동반된 심방세동 환자에서도 유지될 것으로 생각된다.

적응증별 NOAC 용량에 대한 혼동을 피하는 방법

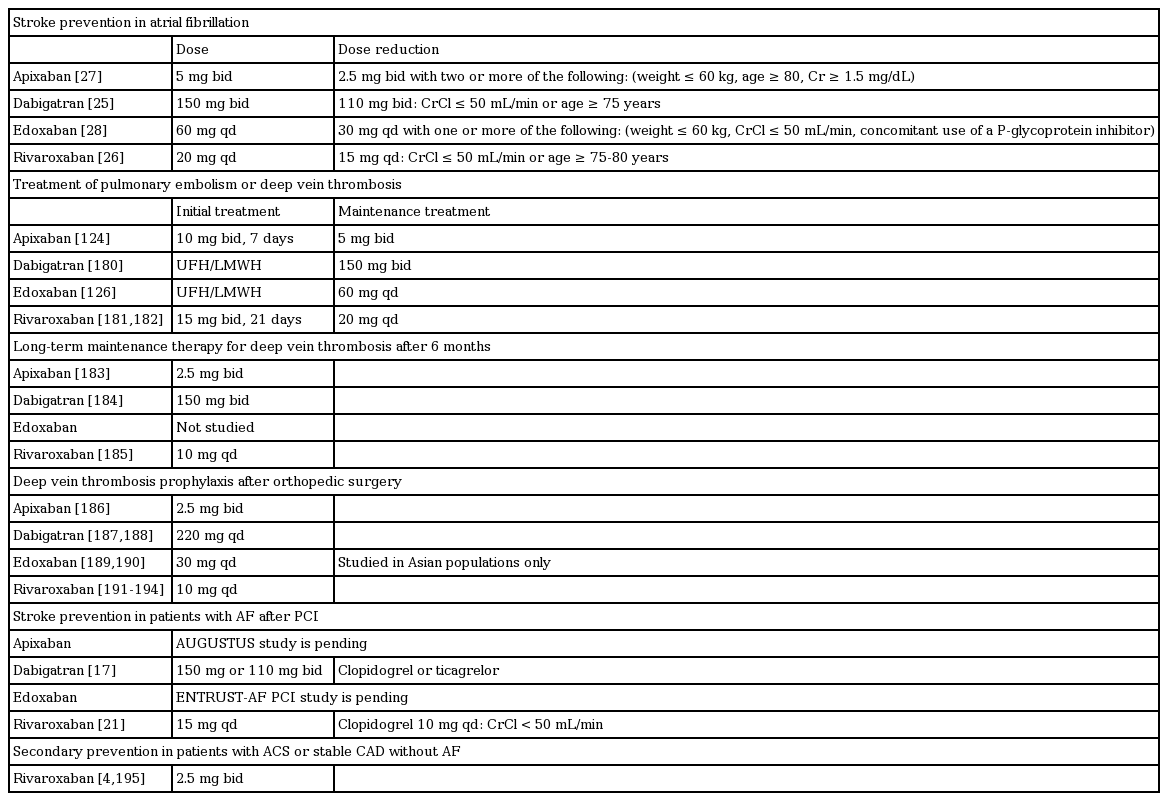

임상시험에서 증명된 NOAC의 좋은 효과를 기대하기 위하여 정확한 용량을 사용하는 것이 매우 중요하다. 네 가지의 NOAC들이 심방세동 외의 다른 적응증에서도 사용되고, 각각 용량 조절 기준이 다르기 때문에 정확한 용량을 사용하는 것이 혼동될 수 있다. 표 1에 현재 사용되는 NOAC의 적응증에 따른 용량 및 용량 조절 기준을 정리하였다.

NOAC를 사용하는 환자에서의 심율동 전환

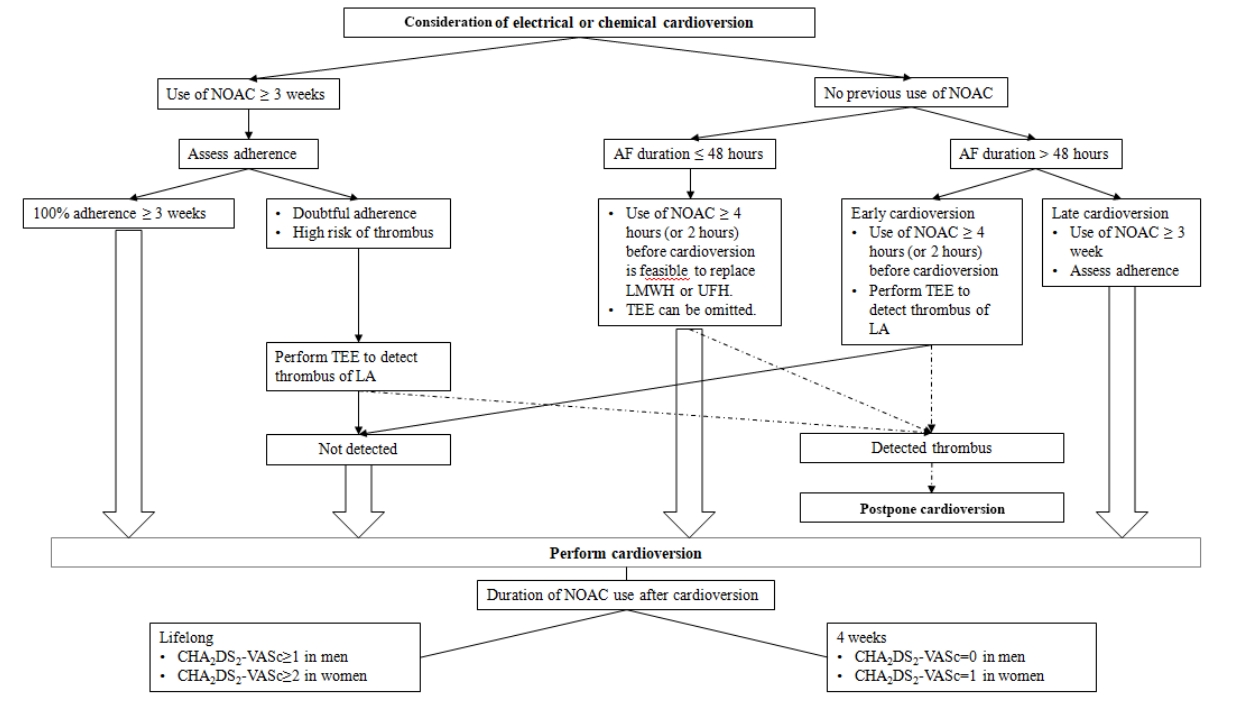

2016년 유럽 및 2014년 미국 심방세동 치료 지침에 따르면 심방세동의 지속기간이 48시간 이상이거나 분명하지 않을 때에는 심율동 전환 전 최소한 3주 이상의 경구용 항응고제를 사용하거나 경식도 초음파를 시행하여 좌심방귀 내의 혈전 유무를 확인할 필요가 있다. 심율동 전환 이후에는 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수에 관계 없이 추가적인 4주의 지속적인 항응고제 사용이 필요하다[11,29]. 심율동 전환을 고려할 때 몇 가지 상황에 따라 구분이 필요한데 지속적으로 NOAC를 복용하던 환자에서의 전기적 심율동 전환, 새로이 나타난 심방세동에 대한 즉각적인 심율동 전환, 항응고제를 복용하지 않고 있던 환자에서 새로이 진단된 심방세동에 대한 심율동 전환이 있다(Fig. 3).

Cardioversion workflow for patients with atrial fibrillation according to duration of atrial fibrillation and previous use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. AF, atrial fibrillation; NOACs, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography.

NOAC를 3주 이상 복용하던 환자에서의 심율동 전환

NOAC를 사용한 초기 무작위 연구를 분석해 보면 NOAC를 복용한 환자에서 전기적 심율동 전환은 와파린을 복용한 환자와 비슷하게 혈전 색전의 위험이 매우 낮았다[25-27]. 이후에 리바록사반, 에독사반 및 아픽사반을 사용한 전향적인 연구들[30-32]에서 NOAC를 3주 이상 사용하였을 때 심율동 전환 이후의 뇌졸중 발생이 와파린과 비교하여 매우 낮음을 확인하였다. 이러한 연구들을 종합해 볼 때 통계적으로 비열등성을 증명할 수 있을 만큼 충분한 환자를 포함하지는 않았지만 만약 심율동 전환 전 3주 동안의 NOAC 사용이 적절하게 이루어진다면 경식도초음파 없이 안전하게 심율동 전환을 할 수 있다는 것을 시사한다[11]. 지난 3주 동안 효과적으로 NOAC의 사용이 이루어졌는지에 대한 정보를 알 수 있는 응고 검사가 없기 때문에 시술 전 환자의 복용 순응도를 확인하고 이에 대한 기록이 필요하다. 만약 NOAC의 복용 순응도가 불확실하다면 심율동 전환 전 경식도초음파를 시행하여야 한다. 중요한 점은 오랜 기간 적절하게 항응고제(비타민 K 길항제 또는 NOAC)를 사용하더라도 좌심방귀에 혈전이 형성될 수 있으므로 시술 전 경식도초음파 시행 유무는 임상가의 결정에 따라야 하겠다. 이러한 결정에 참고할 내용으로 CHADS2 또는 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수가 있다. 항응고제를 사용하던 환자에서 심방세동에 대한 고주파도자절제술 시행 전 경식도초음파를 시행해 보면 1.6-2.1%의 환자에서 좌심방에서 혈전이나 찌꺼기(sludge)가 관찰되었으며 혈전 발생의 위험은 CHADS2 점수와 연관되었다(CHADS2 점수가 0-1점일 경우 0.3% 이하, CHADS2 점수가 2점 이상일 경우 0.5%) [33-35].

NOAC 비복용 환자에서 발생 48시간 이상 심방세동의 심율동 전환

리바록사반, 에독사반 및 아픽사반을 사용한 X-VeRT [30], ENSURE-AF [31] 및 edoxaban treatment versus vitamin K antagonist in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (EMANATE) 연구[32]에서는 항응고제를 사용하지 않았던 환자를 각각 57%, 27% 및 100%를 포함하였기 때문에 이를 통하여 중요한 정보를 얻을 수 있다. 심율동 전환 방법은 경식도초음파를 사용하여 조기 시행하는 방법과 경식도초음파 없이 항응고제를 3-8주 동안 사용하고 지연 시행한 방법이 있었다. 항응고제를 사용하지 않았던 환자의 경우에서 통계적으로 유의하지는 않았지만 혈전색전증의 발생 빈도가 다소 높은 경향을 보였다. 전반적으로 NOAC군과 비타민 K 길항제를 사용한 군 간에 허혈이나 출혈의 사건 발생 빈도에는 차이가 없었다. 단, 아픽사반을 사용한 군에서는 허혈 사건의 발생이 적었다. 또한 조기 또는 지연 시행한 군 간에도 차이가 없었다. EMANATE 연구에서는 약 절반에서 아픽사반을 시작용량으로 10 mg을 투여하였는데(이후 5 mg 하루 2회) 이 환자들에서 출혈 경향이 더 높아지지는 않았다. 시작 용량으로 아픽사반을 10 mg으로 투여하는 것은 현재는 공식적인 복용 방법이 아니지만 추후 변경될 수도 있다. 종합해 보면 심율동 전환시 적어도 4시간 이상 전(아픽사반의 경우 부하 용량 사용을 2시간 이상 전) NOAC를 적어도 한번 사용하고 경식도초음파로 확인 후에 시행하는 것은 안전하고 효과적인 것으로 보인다. 대안으로 만약 혈전색전의 고위험이 아니거나 복용 순응도가 낮지 않다면 적어도 3주 이상 NOAC를 사용한 후 경식도초음파 없이 심율동 전환을 시도하는 방법이 있다.

NOAC 비복용 환자에서 발생 48시간 이하 심방세동의 심율동 전환

최근에 발생한 심방세동의 지속시간이 48시간 이하인 환자에 있어서도 항응고제를 복용하지 않은 군에 비하여 사용한 군에서 혈전색전의 발생 빈도가 낮았다. 이는 특히 CHA2DS2-VASc가 2점 이상이고 심방세동의 지속시간이 12시간 이상인 경우에서 두드러졌다[36,37]. X-VeRT나 ENSURE AF에서는 48시간 이하로 지속된 심방세동 환자에서 현재 관행인 저분자량 헤파린을 한번 사용한 뒤 심율동 전환 후 4주 이상 항응고제를 유지하는 방법처럼 심율동 전환 전 적어도 한번의 NOAC 복용이 적절할지에 대한 내용은 없다. EMANATE 연구에서는 이러한 환자군이 포함되어 있으나 이에 대한 하위 분석은 아직 보고되지 않았다.

이에 대한 자료가 부족한 상황에서 헤파린/저분자량 헤파린을 사용하는 현재 관행을 따르는 것이 신중한 방법일 수도 있다. 48시간 이상 지속된 심방세동 환자에서 NOAC의 사용이 일관되게 효과적이며 안전하고 NOAC와 저분자량 헤파린의 약동학적 특성이 유사하다는 점을 감안하면 저분자량 헤파린을 대신하여 4시간 전(또는 2시간 전)에 NOAC를 한 번 복용하고 심율동 전환을 시행하는 것은 근거가 있다. 하지만, CHA2DS2-VASc가 4점 이상이거나 심방세동 발생 시기가 불분명하다면 경식도초음파를 사용하여 확인하거나 심율동 전환 최소 3주 전부터 항응고제를 사용하는 지연 시행 방법이 권유된다. 잊지 말아야 할 것은 48시간 이하와 이상만으로 구분할 것이 아니라 48시간보다 더 짧은 기간 지속하였던 심방세동도 뇌졸중 발생 위험이 있다는 것이다. 예를 들어 12시간 미만보다는 12-48시간 지속했던 심방세동에서 위험이 더 높다[38].

심율동 전환 후 항응고제 복용기간

지속적인 복용 여부는 환자 개개인의 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수에 따라 결정된다. 2점 이상인 남성과 3점 이상인 여성은 심율동 전환의 성공 유무에 관계 없이 지속적인 항응고제 사용이 필요하다[11]. 이는 폐색전증, 패혈증 또는 주요 수술 등 유발 요인을 가지고 있는 심방세동의 경우에도 마찬가지이다. 48시간 이상 지속된 심방세동의 경우 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수가 낮다면(남자 0점, 여자 1점) 심율동 전환 뒤 4주 동안 지속 복용이 필요하다. 반면에 심방세동이 12시간 미만처럼 더 짧은 경우 얼마나 항응고 요법을 지속해야 하는지는 아직 명확하지 않다. 왜냐하면 심율동 전환 시행에 관계 없이 심방세동은 수시간 또는 수일 동안 심방의 기능에 지장을 주기 때문이다[38].

좌심방귀 혈전이 발견된 환자의 조치

경식도초음파에서 좌심방귀 혈전이 발견되면 심율동 전환을 시행해서는 안 된다. 관찰 연구 및 전향적 연구 결과에서는 NOAC와 비타민 K 길항제로 치료받은 환자에서 혈전 발생 빈도는 차이가 없었다[25,30,39,40]. 아직 각각의 항응고제로 어떻게 좌심방귀 혈전을 치료하는 것이 최선인지에 대한 연구 자료는 없다. 이전의 표준 치료는 비타민 K 길항제를 사용하여 혈전이 사라질 때까지 international normalized ratio (INR)를 엄밀히 조절하는 방법이었다. 최근 전향적인 X-TRA 연구[41]에서는 리바록사반 20 mg 하루 1회를 사용한 표준 치료를 통하여 41.5% (53명의 환자 중 22명)에서 혈전이 치료되었고 이는 헤파린/비타민 K 길항제으로 치료하여 62.5% (96명 중 60명)에서 혈전이 치료되었던 후향적 연구인 CLOT-AF registry의 결과와 유사하였다[41]. 이는 EMANATE 연구에서도 아픽사반을 사용한 경우 52% (23명 중 12명)로 유사하였다[32]. 다비가트란을 사용한 resolution of left atrial appendage thrombus-effects of dabigatran in patients with atrial fibrillation (RE-LATED AF) 연구는 현재 진행 중이다. 종합해 보면 이러한 연구 결과들은 좌심방귀 혈전의 치료를 위하여 NOAC를 사용할 수 있다는 것을 시사하며 현재 이에 대한 자료는 리바록사반과 아픽사반의 경우에 있어서 유용하다. 특히 비타민 K 길항제의 사용이 어렵거나 적절하게 INR의 조절이 힘든 환자에서 선택할 수 있겠다.

NOAC 복용 중 급성 뇌졸중이 발생한 심방세동 환자

현재까지 잘 고안된 임상연구 결과를 보면, 심방세동 환자에서 항응고 요법에도 불구하고 연간 1-2%에서 허혈성뇌졸중이 발생하는 것으로 보고하고 있다. 이렇게 NOAC 치료 중인 심방세동 환자에서 뇌졸중이 발생하는 경우, 약물 복용에 대한 순응도 평가가 필요하다. 입원 당시 복용 중인 항응고제의 혈장 약물 농도 측정은 2차 뇌졸중 발생 예방을 최적화하는데 도움이 될 수도 있다[42]. 더불어, 심방세동에 의한 혈전색전증 이외의 뇌졸중 발생에 관련된 다른 원인이 있는지 평가되어야 한다.

NOAC 치료 중인 심방세동 환자에서의 급성기 뇌졸중 관리

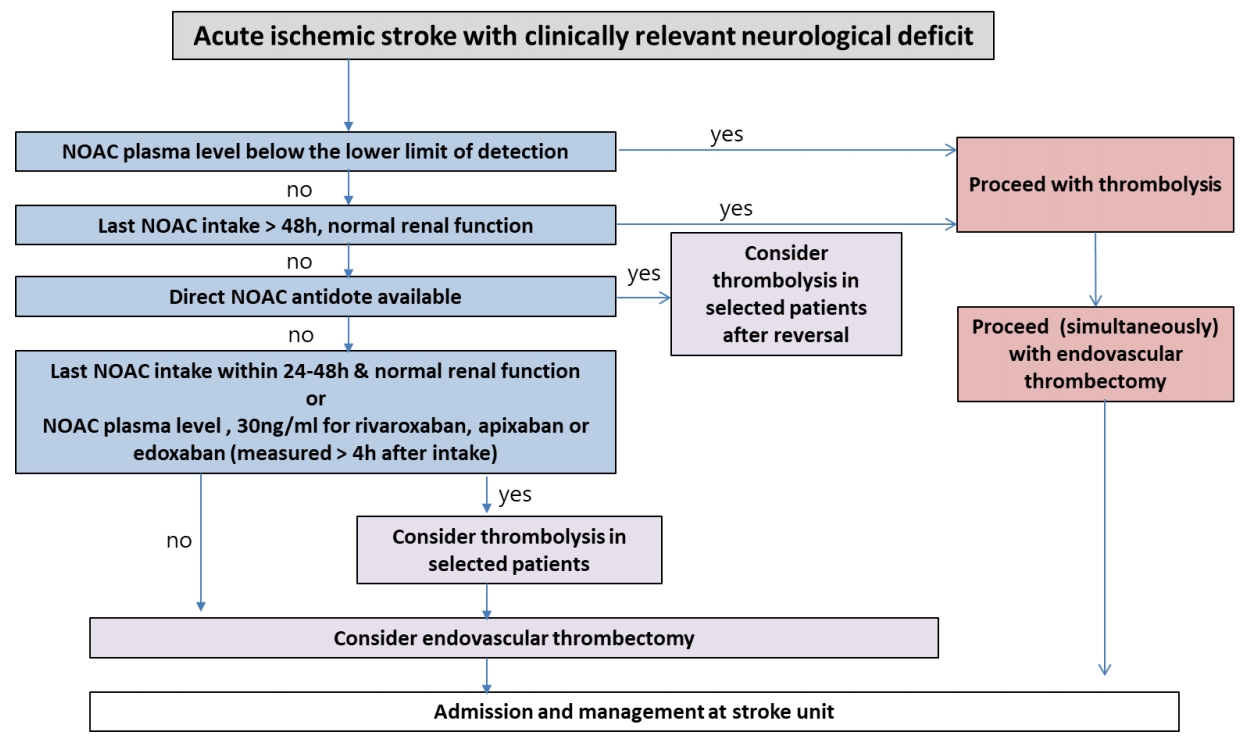

급성 허혈성뇌졸중 환자

급성 허혈성뇌졸중 환자인 경우에는 현행 치료 지침에 따르면, 뇌졸중 증상 발현 4.5시간 이내에 재조합 조직 플라스미노겐 활성인자(rt-PA)투여에 의한 혈전용해요법은 허가되어 있으나, 항응고제를 복용 중인 환자(비타민 K 길항제를 복용 중인 환자는 INR ≥ 1.7인 경우)에서는 투여해서는 안된다(Fig. 4) [43]. NOAC의 경우 혈전용해요법은 NOAC의 반감기 때문에, 마지막 약물 투여 후 24시간 이내에는 진행할 수 없으며, 신기능저하 환자, 고령 환자 또는 다른 상황들에서 반감기가 길어질 수 있다는 것을 고려해야 한다. 다비가트란의 경우에는 역전 작용을 나타내는 약물인 이다루시주맙(idarucizumab) 사용이 가능하다. 이전 증례 보고들에 따르면, 역전 가능 여부 및 응고 상태 평가 후 중등도-중증의 뇌졸중 발생 후 4.5시간 이내의 정맥내 혈전용해요법은 가능하고 안전할 것으로 보인다[44,45]. 현재까지는 이러한 치료 방식의 효과와 안전성을 확인한 무작위 배정 연구가 없기 때문에, 이러한 치료 방식의 기대 효과와 위험도를 균형 있게 판단하는 것이 중요하다. 향후 안덱사네트 알파(Andexanet alpha)의 임상 투여가 허가되면, Xa 억제제를 투여받았던 환자에 대하여 안덱사네트 알파의 역전 치료의 효과 및 안전성에 대한 연구가 필요하다.

Flow chart for the acute management of acute ischemic stroke in a patient receiving NOAC oral anticoagulants. NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; h, hours.

발표된 증례 보고들에 따르면, NOAC의 혈장 약물 농도가 낮은 환자에서는 재조합 조직 플라스미노겐 활성인자 투여가 안전하다고 보고하고 있다[46,47]. 최근까지 많은 발전에도 불구하고, 개별 NOAC에 대한 신뢰성 있고 민감하며 빠른 혈중 농도 검사는 아직까지 대부분 가능하지 않다[42,48,49]. 그러나 NOAC (리바록사반, 아픽사반, 에독사반)에 특이적 혈액 응고 평가(마지막 약물 투여 후 4시간 이상 지난 후 측정)에서 약물 농도가 30 ng/mL 미만인 경우 일부 환자에게 재조합 조직 플라스미노겐 활성인자의 정맥내 투여가 고려될 수 있는데, 이 치료 지침은 전문가의 합의만을 토대로 정해진 것이다[50]. 임상 연구에서 이 치료 방식의 효과와 안전성을 더 평가해야 하기 때문에 응급 상황에서는 사용이 용이한 검사를 실시할 것을 권장한다. 반면 항응고제 상태에 대한 불확실성이 있는 상황(실어증이 있는 경우, 마지막 NOAC 복용 시간을 모르는 경우, 혈장 약물 농도의 빠른 검사가 불가능한 경우)에서는 절대로 혈전용해요법이 권장되지 않는다.

내경동맥 원위부 또는 근위부 중간 대뇌동맥의 폐쇄가 있고, 항응고 치료를 받지 않은 일부의 환자에서는 뇌졸중 발생 7.3시간 이내에 시행한 경피적 혈관내 혈전제거술이 치료 효과가 있다고 입증된 바 있다[51]. 특히, 경피적 혈관내 혈전제거술은 내경동맥의 원위부나 근위부 중간 대뇌동맥의 폐색이 있으면서 마지막으로 증상이 관찰된 후 6-24시간 이내의 관류 불일치가 있는 특정 선별된 뇌졸중 환자에게서만 이점이 있는 것으로 보인다[52,53]. 최근 유럽 뇌졸중학회에서는 경피적 혈관내 혈전제거술을 정맥내 혈전용해요법이 금기인 환자에게서 1차 치료로 권고하고 있으나, 미국 심장학회 지침에서는 아직까지 이와 관련하여 특별한 권고 사항을 제시하고 있지 않다[43,54]. 이러한 권고의 근거가 되는 임상시험은 비타민 K 길항제나 NOAC를 사용한 환자를 제외하거나 소수만 포함하였으나 소수의 데이터는 위에 언급한 특정 환자들에게서 경피적 혈관내 혈전제거술이 안전할 수 있음을 시사하고 있다. 하지만 반드시 주목해야 할 점은 현재 NOAC가 재관류 관련 출혈 위험에 미칠 수 있는 잠재적인 영향을 고려해야 한다. 기계적 재관류를 받은 28명의 NOAC 환자를 포함한 전향적 등록연구에서는 무증상 뇌출혈전환의 빈도가 비교적 높았다[55]. 따라서 전향적 데이터가 반드시 필요하겠다.

급성 두개강내 출혈 환자

NOAC 관련 두개강내 출혈의 약 2/3는 대뇌피질 출혈이고, 약 1/3은 경막하 출혈이다[56,57]. 후향적/전향적 연구의 메타분석에 따르면, NOAC로 인한(다비가트란의 특이 역전제인 이다루시주맙을 사용하지 않았을 때) 두개강내 출혈은 비타민 K 길항제와 유사한 정도의 예후를 보였으나[58], 최근의 대규모 후향적 분석(the get with the guidelines stroke program)에서는 NOAC가 비타민 K 길항제에 비하여 좀 더 좋은 결과를 보였다[59]. 신경과/뇌졸중 전문의들은 NOAC 복용 중 두개강내 출혈이 발현한 모든 환자에 대하여 검사를 하고 신경외과의 협진을 시행하여야 한다고 권고한다.

경구용 항응고제 치료 중 발생한 두개강내 출혈의 치료에 대한 지침은 발표되었으나, NOAC 관련 두개강내 출혈의 치료 근거는 아직 낮다. 와파린 복용 중 급성 두개강내 출혈이 발생된 환자와 유사하게 NOAC 복용 중 뇌출혈이 발생된 환자에서도 약물 중단, 긴급 혈압 관리 및 혈액응고 상태의 신속한 교정이 혈종 확대를 막기 위하여 반드시 필요하다[56,60,61]. NOAC 관련 두개강내 출혈 환자에 prothrombin complex concentration의 사용이 도움이 되는지는 후향적 분석에서 혈종 확대에 중요한 이점을 입증하지 못하였기 때문에, 아직까지는 논쟁의 여지가 있다[62]. 다비가트란 관련 두개강내 출혈에 대한 증례 보고들에 따르면[45], 이다루시주맙으로 치료받은 입원 환자 12명 중 2명에서는 혈종 증가가 관찰되었다. 따라서, 현재의 권고 지침에도 불구하고 역전제 치료의 효능은 불분명하고 향후 임상연구에서 더 평가되어야 할 필요가 있다.

급성기 이후 관리

급성 허혈성뇌졸중 이후의 심방세동 환자

NOAC 치료 중 발생한 허혈성뇌졸중 환자에서 특정 NOAC가 더 선호되거나, 다른 NOAC 약제로 전환한 전향적 대조군 연구는 없다(Fig. 5). NOAC의 적정 용량 및 특이적 상황들은 환자마다 평가되어야 한다[63-65]. NOAC 관련 3상 연구에서는 뇌졸중 발생 후 7-30일 이내의 환자들은 대상군에서 제외되었기 때문에[66], 일과성 허혈 발작 또는 뇌졸중 후 NOAC의 재투여 시기에 관한 실질적인 연구는 아직까지 없다. 그러므로 현재의 지침은 의견 합의에 의한 것이며, NOAC는 비타민 K 길항제를 사용한 임상적 사용과 유사하게 재투약되어야 한다. 허혈성뇌졸중 이후 경구용 항응고제를 다시 시작하는 것은 반드시 뇌졸중 재발 위험이 2차적 출혈 위험보다 커야 한다(Fig. 5) [11,66]. 2018년 유럽 심장학회 지침에서 언급하는 것처럼[11], 일과성 허혈 발작이며 뇌 영상에서 두개강내 출혈이 아닌 것이 확인된 환자에서는 NOAC의 사용을 지속하거나 뇌졸중 발생 하루 후부터 시작한다. 만약 경증의 뇌졸중으로 뇌졸중의 크기가 잠재적으로 2차적 출혈보다 크지 않을 것으로 예상되는 환자의 경우는 경구용 항응고제를 허혈성뇌졸중 3일 이후 시작한다. 중등도의 뇌졸중의 경우는 전산화단층촬영(computed tomography, CT)이나 자기공명촬영(magnetic resonance imaging, MRI)과 같은 반복적인 뇌 영상을 통하여 2차적 출혈 위험이 없는 것을 확인하고 뇌졸중 발생 6-8일 이후, 중증의 뇌졸중의 경우는 12-14일 이후 다시 시작한다[66-68].

Timing of the (re-) initiation of anticoagulation after acute ischemic stroke. TIA, transient ischemic attack; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; h, hours; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants.

NOAC는 작용 발현 시간이 빠르므로 헤파린(저분자량 헤파린 또는 비분획 헤파린)과 병용 투여는 추천되지 않는다. 또한, 메타분석에서 허혈성뇌졸중 후 7-14일 이내에 비경구용 항응고제 투여는 두개강내 출혈을 유의하게 증가시키는 것이 확인되었다[69].

허혈성뇌졸중과 죽상경화증을 동반한 심방세동 환자

허혈성뇌졸중과 죽상경화증을 동반한 심방세동 환자에서 스타틴 치료 요법 이외에도 큰 혈관 질환이 의심되고 출혈 위험이 비교적 낮다고 판단될 경우 선택된 환자에서 NOAC에 항혈소판약제인 아스피린을 일시적으로 추가하는 것을 고려할 수 있다. 그러나 연구는 아직 부족하며, 더 많은 임상연구가 반드시 필요하다. 내경동맥에 무증상의 협착이 있는 심방세동 및 경동맥 죽상경화 환자는 안정형 관상동맥 심장 질환과 유사하게 추가로 항혈소판약제 치료 없이 스타틴 및 경구 항응고제로 치료해야 한다. 심방세동 및 증상이 있는 심한 경동맥 협착을 보이는 급성 뇌졸중 환자는 경동맥내막절제술을 받는 것이 바람직하며[70], 경피적 경동맥 스텐트 삽입술은 항응고 요법 외에 항혈소판 요법을 추가해야 하므로 결과적으로 출혈 위험이 더 커질 수 있다. 경동맥내막절제술을 받는 환자의 경우 수술 전과 수술 후 며칠 동안 아스피린을 복용하는 것이 좋다. 아스피린은 경구용 항응고제를 (재)시작한 후에는 중단해야 한다.

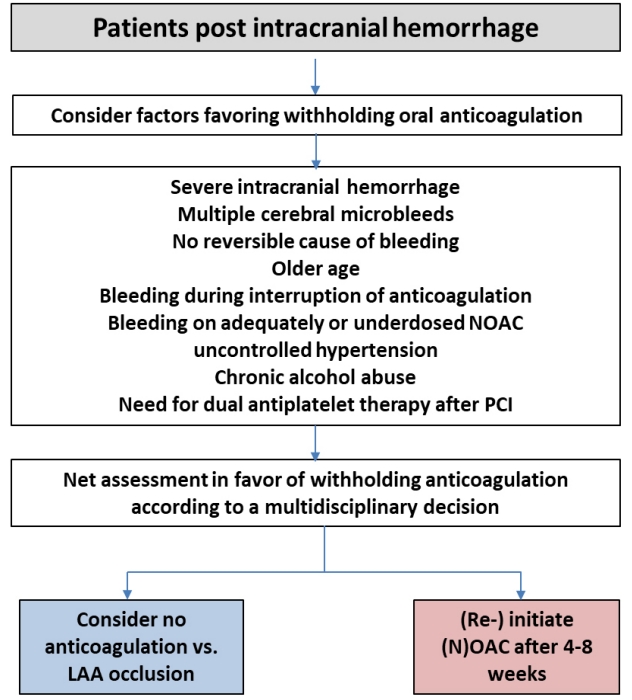

두개강내 출혈 이후의 심방세동 환자

심방세동 환자에서 두개강내 출혈이 발생한 경우에는 두개강내 출혈의 초기 예후와는 별도로, 향후 허혈성뇌졸중 및 사망률과 밀접한 관련을 보이며, 이는 부분적으로 두개강내 출혈 후 항응고제 중단으로 인한 것으로 판단된다(Fig. 6) [71-73]. 두개강내 출혈 후 NOAC 사용에 대하여 임상연구 자료를 기반으로 한 치료 지침은 현재 없다. 두개강내 출혈의 원인(조절되지 않은 고혈압, 동맥류 또는 동정맥 기형, 의학적으로 필요한 항응고 3제 요법)이 해결되지 않은 한, 비타민 K 길항제 및 NOAC의 사용은 금기이다[11]. 최근 관찰 연구들의 메타분석에 의하면, 비타민 K 길항제의 재시작은 재발성 두개강내 출혈 위험을 유의하게 증가시키지 않으면서 허혈성 뇌졸중 발생률을 유의하게 낮춘다고 한다[72]. 그러나 메타분석에서 발생될 수 있는 여러 가지 편견들을 고려해야 한다. 무작위 배정 임상연구가 없으므로, 항응고 관련 두개강내 출혈을 경험한 환자에서 어떤 유형의 항응고제를 투여할지 혹은 투여하지 않을지 여부를 사안별로 고려해야 한다(Fig. 6) [11]. 두개강내 출혈 후 모든 환자에서 적절한 혈압 조절은 가장 중요하다[60]. 또한 두개강내 출혈을 경험한 심방세동 환자에서 경피적 좌심방귀 폐색술이 장기간 항응고 요법을 효과적으로 대체할 수 있다[11]. 그러나 경피적 좌심방귀 폐색술 직후 항혈소판약제의 복용 기간이 필요하므로 두개강내 출혈의 위험도 초래될 수 있다. 현재까지 단기간 항혈소판약제 치료(또는 항응고 치료와의 병행)의 안전성 및 유효성은 알려져 있지 않다. 전반적으로 항응고제 관련 두개강내 출혈 후 경피적 좌심방귀 폐색술에 대한 무작위 배정 임상연구는 부족하다. 따라서, 향후 적절한 치료 지침을 결정하기 위해서 무작위 임상연구가 필요하다.

대뇌피질 출혈 후 심방세동 환자

대뇌피질 출혈 후 심방세동 환자는 비타민 K 길항제 관련 대뇌피질 출혈의 관리와 유사하게, 심인성 혈전색전증에 의한 뇌졸중의 위험이 높고 재발성 두개강내 출혈의 위험이 낮을 것으로 예상되는 경우 대뇌 출혈 4-8주 후 NOAC 투여를 재개할 수 있다[74]. 그러나 실제로는 허혈성뇌졸중 고위험군이나 대뇌피질 출혈 고위험군은 동일한 위험 인자들(고령, 고혈압 및 뇌졸중 기왕력 등)을 가지고 있다[61]. 따라서, 심방세동을 동반한 대뇌피질 출혈 환자에서 항응고 치료를 다시 시작할지 여부는 개별적으로 평가되어야 한다(Fig. 6) [60,75]. 아밀로이드성 뇌혈관질환이 있는 환자는 재발성 두개강내 출혈의 위험이 매우 높으므로 항응고 치료를 해서는 안 된다[73]. 최근 미국 심장학회 치료 지침에서 대엽 출혈 후에는 항응고제 사용을 중단해야 한다고 권고하고 있으나 아직까지 논란의 여지가 있고, 최근 3개의 후향적 연구에 대한 메타분석 결과는 두개강내 출혈 후 항응고제 재개는 사망률 감소와 유익한 임상 경과를 보인다고 보고하고 있다[74].

지주막하 출혈 후 심방세동 환자

지주막하 출혈 후 심방세동 환자에서 경구용 항응고제 재개에 대한 임상연구 결과는 아직까지 부족하다. 혈관조영술을 통한 적절한 평가와 더불어 동반하고 있는 동맥류 또는 동정맥 기형의 적절한 치료가 반드시 요구된다. 또한 재출혈 위험에 대한 신경학적/신경외과적 다학제 평가를 통하여 경구용 항응고제 재개에 따르는 위험과 이익의 균형을 맞추는 것은 매우 중요하다. 만약 NOAC를 복용하고 있는 심방세동 환자에게 치료 가능한 병인이 없는 데에도 지주막하 출혈이 발생했다면, 경구용 항응고제 치료를 재개하지 않는 것이 바람직하다. 현재까지 임상연구 데이터가 없으므로 경피적 좌심방귀 폐색술은 무작위 임상시험이 필요하다.

경막 외 또는 경막하 혈종 후 심방세동 환자

경막 외 또는 경막하 혈종 후 심방세동 환자는 구체적 데이터가 없음에도 불구하고 진행성(만성) 알코올 남용이나 실질적인 낙상 위험이 없는 경우, 외과적 경막 외 혈종 또는 경막하 혈종 수술 약 4주 후부터 항응고제를 재시작하는 것이 안전하다. 임상 양상 및 혈종의 확장에 따라 경구용 항응고제를 재시작하기 전에 뇌 영상 검사(CT 또는 MRI 사용)를 권장한다.

특별한 상황에서의 NOAC

취약한 고령 환자에서 NOAC

75세 이상의 환자

심방세동의 유병률은 해마다 점진적으로 증가하고 있다[76,77]. 뇌졸중의 위험 자체가 나이가 들면서 증가하기 때문에 고령 환자에서 뇌졸중 예방은 중요하다[78]. 그러나 경구용 항응고제는 고령 환자군에서 덜 사용되고 있다[79]. 경구용 항응고제를 쓰는 경우가 쓰지 않는 경우보다 더 나았고, 비타민 K 길항제보다 NOAC를 사용한 경우가 더 나았다[80-82].

총 27,000명이 넘는 심방세동 환자를 비교한 NOAC 치료에 대한 연구들에서는 연구에 따라 31-43%의 유의한 고령 환자(75세 이상)를 포함하였고 메타분석에서 나이에 따른 안전성이나 효과측면에서 유의한 상호작용은 없는 것으로 보였다[83]. 중요한 것은, 절대 위험이 높을수록 고령 환자에게 비타민 K 길항제 대신 NOAC를 사용함으로써 위험이 더 크게 감소했다[84]. 고령의 환자에서 더 많은 출혈이 있었지만 전체적으로 관찰된 출혈의 패턴(두개강내 출혈의 감소와 소화기 출혈의 증가)은 NOAC와 비타민 K 길항제 간에 차이가 없었다[83]. 비타민 K 길항제와 비교한 NOAC의 모든 연구에서 두개강내 출혈이 낮게 나오는 반면, 각각의 연구에서 나이와 출혈의 관계는 다양하였다. 다비가트란은 두 가지 용량에서 나이와 두개 외 주요 출혈 간 유의한 상호작용이 있었다[85]. 하지만 아픽사반, 에독사반, 리바록사반에서는 모두 유의한 차이가 없었다[84,86,87]. 중요한 것은 특정 동반 질환(특히 신부전)은 고령의 환자에서 더 흔하고 따라서 개개인에서 NOAC를 선택할 때 이러한 상황에 대한 고려가 필요하다. 일본인을 대상으로 표준 항응고 치료의 대상이 되지 않는 고령의 심방세동 환자에서 저용량 에독사반 사용에 대한 재미있는 연구가 현재 진행 중이다[88].

취약함과 낙상

취약함(frailty)과 취약함 전단계(pre-frailty)는 고령에서 흔하고 경구용 항응고 치료의 위험-이익에 대한 특별한 고려가 필요하다. 취약함은 표현 모습과 임상적 판단에 따라 대개 취약함 척도(frailty scale)를 통하여 정의된다(Table 2) [89-91].

취약함은 빠른 신기능 악화와 낙상의 위험인자이다. 지역사회에 거주하는 65세 이상에서 연간 1-2%의 낙상 위험이 있다. 이 중 단지 5%만이 골절과 입원을 초래한다[92]. 낙상과 경막하 출혈의 위험이 의사에게는 경구용 항응고제의 금기로 고려되어 왔다[93]. 매우 심한 취약함과 신체 활동 제한 상태 그리고 제한된 기대 여명은 아마도 경구용 항응고제의 이익을 제한할 수 있지만, Markov decision analytic 모델에서는 비타민 K 길항제를 사용하는 경우, 혈종의 위험이 항응고 치료의 이익을 능가하려면 295번 낙상해야 함을 보여주었다[94]. 비타민 K 길항제와 비교하여 NOAC를 사용할 때 혈종의 위험이 매우 낮은 것을 고려하면 NOAC를 사용할 때 그 숫자는 훨씬 더 클 것이다.

낙상의 위험을 계산할 수 있는 도구(Table 3)가 있다. 낙상의 위험이 있는 환자에서 비타민 K 길항제 대비 NOAC의 효과에 대해서는 두 개의 NOAC 연구(effective anticoagulation with factor Xa next generation in atrial fibrillation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction-48 [ENGAGE-AF TIMI 48], apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thrombotic events in atrial fibrillation [ARISTOTLE]) [95,96]에서 각각 분석되었다. NOAC의 치료 효과는 낙상의 위험이 증가된 경우와 그렇지 않은 경우 모두에서 일관되었다.

요약하면, 취약하며 고령인 환자는 뇌졸중의 위험이 높으며 경구용 항응고제로 얻는 이익이 있기 때문에 취약함 그자체로 항응고 치료를 제외해서는 안 된다. 이러한 환자군에서 비타민 K 길항제에 비하여 NOAC가 효과적임을 에독사반과 아픽사반의 3상 연구에서 증명하였다. 리바록사반의 경우 후향적 연구에서 비타민 K 길항제에 비하여 뇌졸중 및 전신색전증 발생 위험을 유의하게 낮춤을 확인하였다[97]. 상황을 개선하기 위하여 경구용 항응고제를 복용하는 모든 낙상 환자에서 추후 낙상 위험을 감소시키기 위하여 진단과 위험 그리고 교정이 가능한 병적 상태, 치료적 중재술(운동 처방, 가정 환경 평가 등) 등을 다원적으로 평가해야 한다[98-100].

치매와 항응고

치매는 고령에서 흔하다. 뇌졸중은 치매가 없는 환자에 비하여 인지기능 저하, 독립성 상실, 시설 의존성의 위험이 큰 치매 환자에게 있어서 매우 의미 있는 사건이다[101]. 그리고 심방세동 그 자체로도 치매의 위험인자이며, 경구용 항응고제가 심방세동 환자에서 치매의 위험을 감소시킬 것이라는 증거들이 있다[102,103].

그러나 치매 환자는 항응고 치료를 선택할 때 독특한 고려를 해야 하는데, 특히 환자의 의사 결정 능력, 치료의 선택 그리고 약을 안전하게 지속 복용할 수 있는 가이다. 중요한 것은 논리적인 관점에서 치매가 잘 관리된다면 치매 자체를 항응고 치료의 일반적 금기로 보지 말아야 한다는 것이다. 모든 치매 환자들은 경구용 항응고제 치료로 인한 뇌졸중과 출혈의 위험에 관한 이해 능력과 치료 결정에 대한 세심한 평가를 받아야 한다. 능력이 부족할 경우 의사는 최상의 의료 이익 원칙을 바탕으로 치료를 권하는 것이 합리적이고, 이상적으로 이는 가족 동의를 포함한다. 경구용 항응고제 복용의 준수는 치매에서 중요한 고려 사항이다. 하루 한번 복용이나 주간 약제 상자, 알림 또는 투명한 포장(blister)이 도움이 될 수 있다. 역설적으로 치매 환자를 돌보는 사람이 치매 환자에게 약을 제공하는 것이 더 높은 약물 복용 순응도를 보였다. 이러한 환자군에서 전자 모니터링이나 전화 모니터링의 이점에 대해서도 더 연구가 필요하다[104].

비만과 저체중

비만

World Health Organization은 과체중과 비만을 각각 body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 그리고 30 kg/m2 이상으로 정의한다. 1975년 이후 비만의 발생률은 3배 증가했고 2016년에 6억 5,000만 명(전세계 인구의 13.1%)의 성인이 비만이었다[105]. 많은 다른 요인들과 함께 비만도 심방세동의 위험을 높이고 성공적인 고주파 절제술 이후 재발의 위험인자이다[106-108]. 이렇듯, 체중 감량은 심방세동과 비만을 가진 환자에서 필수적이다[109].

비만은 약물의 배출뿐만 아니라 체적 분포를 포함한 약물의 약동학(특히 지방 친화성 약물)에도 영향을 준다. 실제로 신혈류와 크레아티닌 청소율은 비만 환자에서 증가되어 있고 이로 인하여 경구용 항응고제의 제거가 증가될 수 있다[110]. 비타민 K 길항제를 복용하는 비만 환자는 INR 값을 유지하기 위한 더 많은 약 용량과 투여 기간이 필요하다[111].

다비가트란 연구에서는 고령의 건강군에서 매우 비만한 환자를 포함하여 분석하지는 않았지만 체중이 약동학 변화에 영향이 없는 것으로 보고했다[112-114]. 리바록사반과 아픽사반의 약동학 데이터는 처음에는 체중에 따른 체적 분포와 반감기가 변한다고 보고하였으나 이는 임상적으로 유의하지 않는 것으로 보였다[115-117].

에독사반 데이터는 저체중이 약제 배출 감소의 인자일 것으로 보고했으나 그 반대인 경우도 가능하다[118]. 비만 환자에서 NOAC의 항응고 효과가 믿을 만 한지에 대해서는 우려가 있어 왔다[119,120]. 심방세동이나 정맥혈전색전증 환자의 NOAC 연구에서 체중은 제외 기준에 포함되지 않았다. 하지만 BMI 40 kg/m2 이상의 아주 심한 비만에서 다비가트란의 낮은 혈중 농도로 인하여 치료에 실패한 증례는 보고된 바 있다[121,122].

아픽사반은 60 kg 이상과 이하 환자에서 효능과 안전성에서 차이가 없었다[27]. 그러나 BMI 30 kg/m2 이상의 환자들은 조금 더 좋은 결과를 보였다[123]. 이것은 정맥혈전색전증에서 아픽사반 치료에 대한 연구인 apixaban for the initial management of pulmonary embolism and deep-vein thrombosis as first-line therapy (AMPLIFY)에서 비만환자 그룹의 출혈 감소와 대조되는 결과이다[124]. 비슷한 결과로 rivaroxaban once daily oral direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation (ROCKET-AF) 연구에서 BMI 35 kg/m2 이상의 비만 환자가 다른 코호트들과 비교하여 뇌졸중 위험의 감소를 보였고, BMI에 따라 리바록사반과 와파린의 효과와 안전성에 대한 상호작용이 없었다[125]. ENGAGE-AF 연구는 아직 체중에 따른 에독사반의 안전성과 효과에 대한 하위 분석 결과를 보고하지 않았다[28]. 급성 정맥혈전색전증에서 에독사반을 사용한 임상시험 데이터에서 100 kg 이상의 환자 611명을 포함한 체중별 하위 분석 결과 안전성과 효능에 차이가 없었다[126].

매우 비만한 경우에는 연구 결과가 제한적이기 때문에, BMI 40 kg/m2 이상 또는 체중이 120 kg를 초과하는 경우에는 비타민 K 길항제를 사용할 것을 권하고 있다(국제혈전지혈학회 권고와 일치) [119]. NOAC가 필요한 매우 드문 경우에서는 특정 약물의 농도를 측정하는 것을 고려해야 한다. 그러나 이는 혈액학자의 지침을 따르는 경우로 제한해야 하며 그러한 접근에 대한 명확한 임상 데이터가 존재하지 않는다는 것을 인지하고 이루어져야 한다.

저체중

저체중에 대한 통합된 정의는 없고 향후 기준도 아시아인이 더 작고 마른 경향이 있으므로 인종 특징적으로 정의할 필요가 있다. 저체중은 NOAC에 대한 노출을 증가시킬 수 있고 그러므로 출혈의 위험이 증가한다[127]. 중요한 것은 저체중 환자는 뇌졸중의 위험을 증가시키는 다른 조건 또는 동반 질환인 출혈, 고령, 취약함, 암, 신부전 등과 자주 함께 나타난다. 특히 신장 기능은 근육량이 감소했기 때문에 저체중 환자에서 과대 평가될 수 있다(특히 MDRD 공식으로 계산한 경우). 따라서 이러한 환자에서 항응고 치료할 때는 특별한 주의가 필요하다.

60 kg 이하는 에독사반뿐만 아니라 80세 이상이거나 크레아티닌 ≥ 1.5 mg/dL가 동반되었을 경우 아픽사반의 용량 감량의 기준이다. 이 약제들은 와파린과 비교하였을 때 저체중 환자에서도 효과와 안전성은 다른 코호트와 비교했을 때 일관되게 나왔다[27,28]. 따라서 두 약물은 60 kg 이하 환자에서 선호되는 선택이 될 수 있겠다.

다비가트란은 50 kg 이하 환자의 사후 분석에서도 안전성과 효능이 다른 코호트와 비교하여 일관성 있게 나타났다[25]. 그러나 다른 관찰 연구에서는 BMI 23.9 kg/m2 미만의 저체중 환자는 출혈의 독립 위험인자로 제시되었다[128]. 또한 다비가트란은 저체중 환자에서 신부전이 같이 잘 동반되므로 덜 선호하게 되었다. 리바록사반은 저체중 환자의 탐색분석에서 유사한 효과와 안전성을 보였지만 70 kg 이상과 이하의 환자군 만을 비교하였다[26]. 표준 용량을 복용하는 60 kg 또는 50 kg 이하의 환자에서는 자료가 없는 실정이다.

50 kg 이하의 매우 심한 저체중 환자는 대규모 임상연구에서 매우 적은 수였다. 따라서 체중을 기본으로 용량 감량하는 NOAC (아픽사반, 에독사반)의 경우에도 이러한 환자들에 대한 데이터가 제한적이다. 물론 저체중 환자의 비타민 K 길항제 요법은 출혈이 증가될 수 있다[128]. 만약 NOAC 치료가 이러한 개인에게 필요하다면 혈중 농도의 측정은 약물 축적 정도를 확인하기 위하여 고려될 수 있다[129].

가임기 여성

모든 경구 항응고제는 가임기 여성에게 주의하여 고려되어야 하고 적절한 검사를 하여 임신을 배제하고 약제를 시작하기 전에 피임 상담이 이루어져야 한다. 자궁 이상 출혈은 가임기 여성의 9-14%에서 발생하고 이는 경구 항응고제로 악화될 수 있다[130,131].

가임기 여성의 급성 정맥혈전색전증 치료에서 NOAC를 사용하였을 때 출혈 위험이 와파린 대비 증가됨이 보고되었다. 리바록사반은 와파린과 비교하여 좀 더 긴 월경 출혈기간(8일 이상)과 관련이 있었고(27 vs. 8.3%, p= 0.017), 월경 과다와 관련된 내과적 혹은 외과적 중재술의 필요가 증가했으며(25 vs. 7.7%, p= 0.032) 항응고 치료의 조절이 필요한 경우가 더 많았다(15 vs. 1.9%, p= 0.031) [132]. 리바록사반의 이상 자궁 출혈에 대한 경향은 enoxaparin과 비교한 연구에서도 역시 보고된 바 있다[133]. 아픽사반은 AMPLIFY 연구에서 enoxaparin/와파린 대비 질 출혈 위험도가 증가하였고(45 vs. 20%, odds ratio [OR] 3.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.8-6.7), 폐경 전 여성의 질 출혈은 주로 좀 더 긴 월경 출혈과 관련이 있었다(OR 2.3; 95% CI 0.5-11) [134]. 에독사반은 Hokusai-venous thromboembolism (VTE) 연구에서 와파린 대비 질 출혈 위험도가 증가하였다(hazard ratio [HR] 1.7, 95% CI 1.1-2.5). 에독사반은 와파린 대비 주요 질 출혈 위험도 증가(OR 2.8, 95% CI 0.8-10.8), 임상과 연관되지 않는 경증(clinically relevant non-major) 질 출혈 위험도 증가와 관련이 있었고(OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0-2.4), 75% 이상의 환자에서 항응고제 조절이 필요하였다[135]. 등록 연구에서 가임기 여성 178명에서 factor Xa inhibitor를 복용하는 경우 32% 이상 자궁 출혈이 발생하였다고 보고하였다[136]. 대부분의 경우에서 호르몬이나 항응고 치료를 변경 또는 일시적 중단하여 성공적으로 조절되었다. 일부 저자들은 심방세동이 있는 가임기 여성 환자에서 NOAC의 연구 자료가 부족하다고 우려를 표명해 왔다[137]. 어떤 경우든 NOAC를 복용하는 여성은 월경 출혈의 증가 위험에 대하여 상담받아야 하고 NOAC 복용을 시작한 이후 첫 주기 동안은 주의 깊게 관찰하여야 한다[138].

경구용 항응고제를 복용하는 동안 이상 자궁 출혈이 있는 모든 환자는 구조적 문제와 이상자궁출혈의 재발 위험을 감소시키기 위한 국소 호르몬 치료의 가능성과 수술적 치료에 대하여 산부인과적 평가가 필요하다. 중요한 것은 모유 수유뿐만 아니라 임신 시에도 NOAC는 금기이다.

운동 선수에서 NOAC

심방세동은 운동 선수에서 가장 흔한 부정맥이고, 특히 지구력 운동 선수에게 더 취약하다[139-142]. 뇌졸중에 대한 추가적인 위험인자는 이 그룹에서 흔하지 않다. 그러나 고령에서 경쟁적 또는 격렬한 운동을 하게 되는 경우가 점점 증가한다[143].

CHA2DS2-VASc 점수가 1점 이상인 남성, 2점 이상인 여성에서 현 지침에 따라 항응고 치료가 필요하다[144]. 정맥혈전색전증에 대한 항응고 치료를 하는 선수들에게 전통적인 조언은 치료를 받는 동안 접촉하는 운동을 피하라는 것이었다. 그리고 심방세동이 있는 운동 선수 집단에서 NOAC의 사용에 대하여 보고된 바는 거의 없다. 하루 한번 복용하는 약물은 연습 중 높은 수준의 약물 농도를 피하기 위하여 저녁에 약물을 복용하는 것이 선호된다. 하지만 이를 지지하는 연구는 없다. 심방세동을 가진 모든 선수는 반드시 심장학적 평가를 받아야 한다.

간질

뇌졸중이 발생한 환자의 5% 이상에서 발작의 위험이 있다고 보고되었다[145,146]. 뇌졸중 이후 특별한 원인 없는 발작은 차후 10년 이내 원인 없는 발작 발생 위험이 65%이다[147]. 경구용 항응고제 복용시 발작 중 외상으로 인한 위험이 있다. 고령 또는 뇌졸중 후 환자에서 대부분의 발작은 국소성으로 시작한다. 하지만 드물게 전신화된 무긴장 발작 환자는 두부 손상에 취약하고, 혀 깨물기에 취약하다.

항경련제의 다양한 잠재적 상호작용을 통하여 항응고제가 영향을 받는다[148]. 많은 항경련제가 추가적으로 혈소판 감소나 기능 장애를 유발할 수 있다. 이러한 약물-약물 상호작용의 유의성은 여전히 많은 부분이 알려져 있지 않고 단지 몇몇 증례만 보고되었다. 때로는 NOAC의 약물 상호작용이 매우 심하여 관련 약제가 선호되지 않을 수 있다.

악성종양이 동반된 심방세동 환자에서 항응고 치료

악성종양 환자에서 문제점

고령 환자에서 암은 심방세동처럼 드문 상황이 아니다. 한 연구에서 암환자 중 기존에 심방세동이 있는 경우는 2.4%, 새로운 심방세동은 1.8%의 빈도를 보인다고 보고하였다[149]. 암과 이에 대한 치료는 심방세동을 조장하고, 연령과 암이 모두 혈전과 출혈의 독립적인 위험인자이다.

암환자에서 심방세동의 발생률 및 빈도가 높은 것은 동반 질환(고혈압 혹은 심부전)의 존재, 직접적인 종양의 효과(탈수, 불안 혹은 통증에 따른 교감신경 톤의 변화, 전신적 염증) 혹은 암 치료의 부작용(폐암 수술 후 혹은 tyrosine kinase 억제제인 ibrutinib과 같은 특정 표적 치료의 부작용) 등의 결과일 수 있다[150-153]. 활동성 혹은 과거 암환자에서 생존율 증가는 추가적으로 심방세동의 빈도를 증가시킬 수 있다.

정맥혈전색전증의 위험도는 암이 있으면 다양한 기전으로 증가하게 된다[154]. 뇌, 췌장, 난소, 폐 혹은 혈액암뿐만 아니라 많은 암 치료(예, cisplatin, gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, 적혈구 형성 인자, 과립구 집락 자극 인자)는 특히 혈전색전위험도 증가와 연관된다[155].

반대로, 암은 간 침범을 통하여 간부전을 유발하여, 혈소판감소증 혹은 응고 장애, 출혈 위험도를 증가시킬 수 있다. 종양은 혈관을 침범할 수도 있는데, 많은 소화기 및 신장암, 전이성 흑색종 등의 고형암은 매우 혈관이 잘 발달되어 있고, 출혈이 잘 발생할 수 있다. 혈액암은 응고 장애를 유발하여서, 출혈의 위험도를 증가시킬 수 있다. 더불어서 수술, 방사선 치료, 약물 치료와 같은 모든 암 치료는 출혈을 유발할 수 있다. 국소 수술 부위 상처(수술), 조직 손상(방사선 치료), 전신적 증식 억제 치료(항암치료 및 일부 방사선 치료)는 혈소판 수 및 기능을 감소시킬 수 있다.

악성종양이 동반된 심방세동 환자에서 항응고 치료

암환자에서 보고된 무작위 임상연구인 Hokusai-VTE Cancer 연구 및 anticoagulation therapy in selected cancer patients at risk of recurrence of venous thromboembolism (SELECT)-D 연구는 정맥혈전색전증에서 각각 에독사반 또는 리바록사반과 저분자량 헤파린을 비교하였고, 심방세동 환자를 대상으로 한 것은 아니다[156,157]. 에독사반은 재발성 정맥혈전색전증 및 주요 출혈의 일차 종결점에 비열등한 결과를 보였다. 재발성 정맥혈전색전증은 에독사반이 낮은 경향, 주요 출혈은 높은 경향을 보였고, 이런 결과는 위장관 암환자에서 상부 위장관 출혈의 위험도 증가로 기인하였다. 리바록사반도 정맥혈전색전증의 재발은 상대적으로 낮으나, 임상적으로 중요하지 않은 출혈은 증가하는 결과를 보였다. 이런 결과와 유사하게, 몇몇 소규모 정맥혈전색전증 환자군을 포함한 메타분석에서 비타민 K 길항제 혹은 저분자량 헤파린과 비교시 NOAC는 정맥혈전색전증 예방에 있어서는 동일 혹은 더 좋은 효과를 보였고 주요 출혈은 높은 결과를 보였다[158,159]. 대부분의 암 환자는 일부 활동성 치료 혹은 고식적 치료만 하는 사람이 아니면 임상적으로 안정적일 수 있다. 하지만 어느 정도까지 이러한 결과가 적용될지는 추가적 연구가 필요하다.

심방세동이 있는 암환자에서 전통적으로 비타민 K 길항제 혹은 저분자량 헤파린이 NOAC보다 선호되었다. 왜냐면 이러한 약제가 모니터링이 가능하고 역전제가 있기 때문이다. 하지만 심방세동 환자에서 저분자량 헤파린이 뇌졸중 예방 효과가 있는지 증거가 부족하며, 급성 뇌졸중 상황에서 이차 예방으로 저분자량 헤파린은 금기이다[69]. 활동성 암은 대부분의 NOAC 연구에서 제외 기준이었고, 3상 심방세동 연구에서 일부 포함이 되었지만 암의 유형 및 병기에 대한 임상적 정보가 부족하다. 활동성 암 및 암 과거력을 가진 환자를 분석한 ARISTOTLE 연구에서 아픽사반은 와파린보다 우월한 효과 및 안정성을 암의 유무와 무관하게 일관적으로 보였다[160]. 리바록사반도 유사한 결과를 보였다[161]. 대규모 등록 연구에서 비타민 K 길항제 혹은 NOAC를 암 유무와 관련 없이 처방을 기준으로 조사한 결과에서 출혈, 혈전색전증의 위험도가 동일하였고, NOAC에서 둘 다 조금 낮은 경향을 보였다[162]. 최근 활동성 암으로 치료받고 있는 심방세동 환자를 대상으로 한 대규모 후향적 연구 결과에서 아픽사반은 비타민 K 길항제보다 더 적은 출혈 위험도를 보였다[163]. 국내에서도 NOAC가 비타민 K 길항제보다 우월한 효과를 보인다고 보고하였다[164]. 하지만 NOAC와 특정 항암제의 약물 상호관계는 알려져 있지 않고, 추가적 주의가 필요하다[165].

전반적으로 암을 동반한 심방세동 환자에서 항혈전 치료는 다학제적 팀 접근법이 필요하다[166]. 특히 골수 억제 약물 치료 혹은 방사선 치료가 계획된 경우 NOAC를 일시적 용량 감량 혹은 중단할지는 혈소판, 신장/간기능, 출혈의 물리적 사인 등을 고려해서 생각해야 한다. 양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor) 혹은 H2 억제제를 통한 위장 보호도 고려되어야 한다.

비타민 K 길항제의 용량 조정 최적화

심방세동 환자에서 NOAC의 선호에도 불구하고, 기계 판막 환자와 류마티스성 승모판협착증을 포함하는 특정 상황에서는 아직도 비타민 K 길항제의 사용이 필요하다[144]. 따라서 비타민 K 길항제 치료를 잘 숙지하고, 치료 범주에 유지하는 것이 중요하다.

표준 목표인 INR 2.0-3.0을 유지하는 것이 필요하며, 그 방법은 경험에 의하여 만들어졌다. 비타민 K 길항제 치료에 다양한 알고리듬이 있고[167,168], 지난 수십 년간의 경험이 다른 임상적 방법을 만들어냈다(예, 항응고 크리닉, point-of-care 장비를 이용한 자가 측정). 비타민 K 길항제 치료의 성공은 적절한 치료 항응고 범주 시간(time in therapeutic range, TTR)을 길게 유지하여 허혈 및 출혈의 위험도를 낮추는 것이다. 반대로 낮은 TTR이 지속적으로 관찰되면 치료 방법의 변경이 고려되어야 한다.

치료를 시작하는 동안의 용량

자동 용량 계산기가 있어서 최상의 치료 용량의 결정에 도움을 받을 수 있다(예, http://www.warfarindosing.org). 급성 정맥혈전색전증 환자에서 시작 용량으로 와파린 10 mg과 5 mg을 비교한 한 무작위 연구에 따르면 10 mg으로 시작하는 것이 빠르게 치료 수준의 INR에 도달하였다[169]. 하지만 메타분석에서 시작 용량으로 두 용량 간 우월성 차이는 없었다[170]. 심방세동 환자들은 정맥혈전색전증 환자에서 비하여 더욱 고령이며 취약하다. 또한 심방세동 환자는 일반적으로 급성 혈전 상황에서 투약이 시작되는 것은 아니다. 실제로 고령, 취약함, 신부전과 같은 다양한 인자를 고려하면 저용량 혹은 2 mg 정도의 아주 저용량을 시작하는 것이 적합할 수 있다. 이처럼 저용량 혹은 고용량 중 어떤 것으로 시작하는 것이 좋다는 증거가 부족하므로, 환자의 상태에 맞추어 시작하는 것이 권유되고 있다. 유전자형을 참조하는 약물 용량 조절은 근거 부족으로 권장되지 않는다[168,171].

유럽의 많은 나라에서 펜프로쿠몬(phenprocoumon)으로 항응고 치료를 할 때 반감기가 길어서 적정 항응고 수준에 빨리 도달하기 위하여 부하 용량으로 시작하는 경우가 많다[172]. 반면에 와파린 및 아세노쿠마롤(acenocoumarol)로 시작하는 경우는 어떤 용량으로 시작할지 불분명하다[173]. 비타민 K에 의존적인 항응고 단백질인 C 및 S의 감소에 따른 일시적 혈전 생성 경향의 악화를 예방하기 위하여 항응고 요법 처음에(특히 펜프로쿠몬으로 시작하는 경우) 주사제 항응고 요법을 종종 병행하기도 하지만 이러한 방법의 근거도 불분명하다.

유지 용량

환자들마다 적정 와파린 용량의 다양성은 무척 크다. 심지어 과거 안정적이었던 환자에서도 질병, 식사 변화, 투약 등으로 INR의 심한 변화가 생길 수 있다. 와파린 용량 조절 방법도 센터별 차이가 크지만, 용량 조절 알고리듬이 비타민 K 길항제 용량 및 TTR을 적절하게 하는데 유용하다[174-176]. 표 4는 randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) 연구의 와파린군에서 사용한 알고리듬이다. 개념상 중요한 점은 와파린 용량은 매일매일 용량을 결정하는 것보다는 1주일 동안 들어가는 용량을 바탕으로 용량을 조절해야 한다. INR을 최소 4주에 한번은 측정하고 적절한 INR 수준이 아니면 최소 매주 측정하는 것이 중요한 전제 조건이다. 유사한 약물 투입 계획이 반감기기 훨씬 긴 펜프로쿠몬 및 짧은 아세노쿠마롤에도 사용할 수 있다.

자주 적절한 INR 수준에서 벗어나는 환자에서는 추가적으로 비타민 K 길항제 투약의 위험 및 이득에 대한 교육이 필요하며 약물 복용의 준수, 음식-약제 및 약제-약제 간의 상호작용의 중요성을 알려주어야 한다. 전용 항응고 클리닉에서 치료를 받거나[177,178], 자가 모니터링, 자가 관리 등이 INR 조절을 향상시킬 수 있다[179]. 하지만 환자 선택이 중요한 요소이며, 모든 환자에서 적합하지는 않다.

요약하면 비타민 K 길항제 치료 환자에서는 환자의 TTR을 적절하게 하기 위하여 노력을 해야 한다. 하지만 치료 범주에 있다고 해서 출혈을 완전히 예방하는 것은 아니다. 최근의 연구에서 비록 두개강내 출혈이 INR이 3을 초과하면 증가하고, 4-5를 초과하면 명백하게 증가하지만 대부분의 발생은 치료 범주인 2-3 사이에 가장 많다[58]. 따라서 INR 2-3 사이로 치료 범주 유지는 상대적으로 효과적이며 안전하지만 절대적은 아님을 염두에 두어야 한다.

결 론

심방세동 환자에서 혈전색전증을 예방하기 위해 NOAC는 한국에서 우선시되는 약제로 대두되었다. 관상동맥질환이 동반되는 경우, 용량 혼동시, 심율동 전환시, 뇌졸중 발생시 또는 악성종양이 동반되는 경우에도 본 지침에서 제시하는 바와 같이 사용할 수 있겠다.

Acknowledgements

자료 수집에 도움을 주신 한국비엠에스 제약 채송화, 바이엘 코리아 최종원, 보령 제약 이승연, 한국 다이찌산쿄 박원님께 감사를 드립니다.