면역 능력이 있는 성인에서의 장폐색을 동반한 단일 공장 결핵 1예

Solitary Jejunal Tuberculosis with Intestinal Obstruction in an Immunocompetent Patient

Article information

Trans Abstract

Intestinal tuberculosis is an infection of the gastrointestinal tract by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. To the best of our knowledge, solitary intestinal tuberculosis accompanied by intestinal obstruction, particularly in the middle of the small intestine, is extremely rare. We report a case of solitary jejunal tuberculosis in a 49-year-old man with no underlying disease. He was admitted a few days after the onset of diffuse abdominal discomfort. Upon evaluation, we initially considered a malignancy of the distal jejunum with ileus due to the presence of a mass. Therefore, he underwent laparoscopic resection of the small bowel. Unexpectedly, the histologic specimen showed a chronic caseating granulomatous lesion with acid-fast bacilli. Ultimately, he was diagnosed with solitary jejunal tuberculosis. He was successfully treated with anti-tuberculosis drugs without any complications.

INTRODUCTION

There are numerous ailments such as cancer, complications from of a previous operation, hernia, inflammatory bowel disease, or infectious disease that can cause intestinal obstruction [1]. Although a number of methods have been developed to distinguish between such ailments, differential diagnosis remains challenging [2]. Any decision to perform a surgical intervention, in particular, needs to be made in a timely manner, but such an intervention can leave some patients with an unnecessary scar [1]. Here, we report a case of solitary jejunal tuberculosis (TB) that was misdiagnosed as jejunal cancer with intestinal obstruction and present a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old man was admitted due to diffuse abdominal discomfort for a few days. He had abdominal colicky pain especially in his right lower quadrant, sometimes accompanied by squeezing pain lasting for less than 5 minutes. He had poor oral intake due to abdominal discomfort but no weight loss. He had no medical history, operation history, or family history. He was not a heavy drinker and had a smoking history of only 10 pack-years.

His vital signs included a blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg, heart rate of 72 beats/min, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and a body temperature of 36.5℃. He had no cervical lymphadenopathy, and heart and lung examinations were unremarkable. His abdomen was soft and flat, with hypoactive bowel sounds, and there was no organomegaly or palpable mass. There was tenderness over his right lower quadrant. Laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell count of 14,630/mm3 (neutrophil 84.9%, lymphocyte 8.7%, and monocyte 5.2%), hemoglobin of 16.2 g/dL, platelet of 233,000/mm3, blood urea nitrogen of 12.9 mg/dL, creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL, aspartate transaminase of 19 IU/L, alanine transaminase of 15 IU/L, sodium of 145 mmol/L, potassium of 5.1 mmol/L, albumin of 4.7 g/dL, C-reactive protein of 0.44 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase of 337 IU/L, carcinoembryonic antigen of 1.55 ng/mL, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 of 5.40 U/mL. Chest radiography identified an old TB scar in the left upper lung, which was the same as previous chest images for routine medical checkup. Erect abdominal radiography showed a small bowel ileus (Fig. 1A).

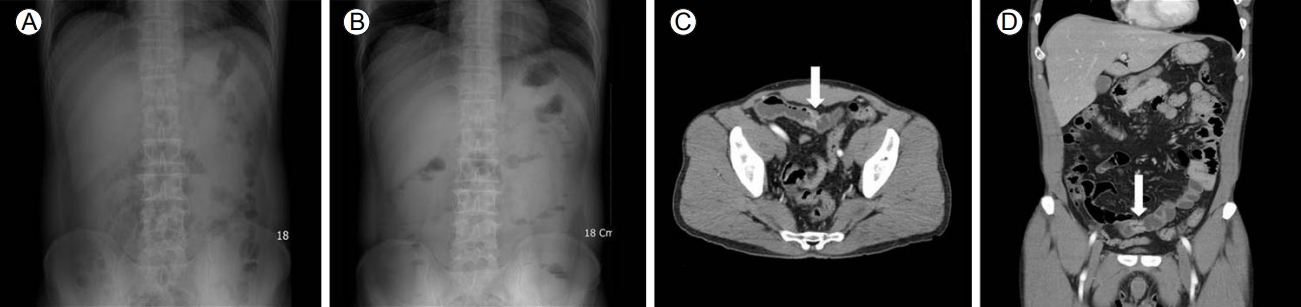

Erect abdominal radiography on the day of admission (A) and the day before admission (B), showing the progression of small bowel dilation over 1 day. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography, axial (C) and coronal (D) views, both showing focal circumferential enhancing wall thickening and luminal narrowing at the jejunum, with proximal dilation (arrows).

The patient had, in fact, visited one day before his admission. At that time, his bowel sounds were hyperactive and erect abdominal radiography did not reveal obstructive pattern (Fig. 1B). However, on his second visit, we were unable to completely rule out intestinal obstruction. This was because his symptoms had become aggravated over the previous day, his bowel sounds became hypoactive, and abdominal radiography showed progression of small bowel dilation (Fig. 1A and 1B). Thus, we obtained abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) instead of endoscopy and colonoscopy. In CT, there was a focal circumferential enhancing wall thickening and luminal narrowing at the distal jejunum, with proximal dilation (Fig. 1C and 1D). However, there were no other findings such as organomegaly or lymph node enlargement.

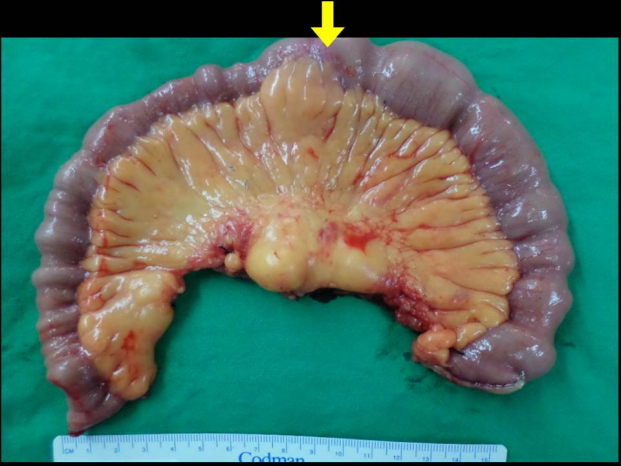

Our initial impression was cancer of the distal jejunum with intestinal obstruction, and he therefore underwent laparoscopic resection of the small bowel. From the gross specimen, we identified a single jejunal obstructive mass with distal narrowing, consistent with our original thoughts (Fig. 2). Upon opening the specimen, several mesenteric lymph nodes showing transmural ulceration through all layers of the tissue were found. Microscopic findings demonstrated a chronic caseating granulomatous lesion in the submucosa and proper muscle layer with multinucleated Langhans-type giant cells and epithelioid cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, acid-fast bacilli in Ziehl-Neelsen staining were found (Fig. 3B).

Gross specimen of laparoscopic-assisted small bowel resection. The specimen consists of a segment of small intestine, from the distal jejunum to the proximal ileum, measuring 34.0 cm in length and 5.5 cm in maximum circumferential diameter. There is a small bowel stricture with obstruction in the distal jejunum. The noted area (arrow) is located 18.0 cm and 20.0 cm from both resection margins.

Pathologic findings of the distal jejunum. (A) Chronic caseating granulomatous lesion in the submucosa and proper muscle layer with multinucleated Langhans-type giant cells and epithelioid cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400). (B) An acid-fast bacillus (arrow; Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1,000).

He was ultimately diagnosed with solitary jejunal TB and began treatment with anti-TB drugs. For the initial 2 months, he took 400 mg isoniazid, 600 mg rifampin, 1,200 mg ethambutol, and 1,500 mg pyrazinamide once daily. For the next 4 months, he continued taking 400 mg isoniazid, 600 mg rifampin, and 800 mg ethambutol once daily, and finished the treatment without any complications.

He was followed at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 6 months after taking the medications. He had no adverse reactions during the treatment period. His laboratory findings were all normal at each visit.

His last visit was 1 month after finishing the anti-TB treatment. He underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. His laboratory and endoscopic findings were all normal.

DISCUSSION

According to the World Health Organization’s Global Tuberculosis Report 2015, the global incidence of TB has decreased by 1.5% every year since 2000 [3]. Similarly, the total annual cases of newly diagnosed TB in Korea have decreased since 2011 [4]. However, the percentage of extrapulmonary TB in Korea has increased from 15% to 20% in the last few years [4].

Intestinal TB is the third most common extrapulmonary TB in Korea, after pleura and lymph node TB [5]. The incidence of intestinal TB was only 8% of extrapulmonary TB in 2008, but this rose slowly but steadily to 18% by 2015 [4]. The possible modes of infection include mucosal infection through food or sputum, hematogenous spread, or direct extension from adjacent tuberculous lesions [2]. The most common sites of the gastrointestinal tract are the ileocecal and jejunoileal areas [6]. The jejunoileal area refers to a continuous lesion arising from the primary ileal region [2,6-8].

Because of the vague clinical symptoms and nonspecific laboratory findings, the early diagnosis of intestinal TB is extremely difficult [2,6]. A high index of clinical suspicion, although essential and important, is often insufficient for diagnosis, and surgery is often required for diagnosis and the management of complications [5-7]. Treatment of intestinal TB is the same as that of pulmonary TB, and the treatment response is quite dramatic [7]. There remains controversy in terms of the treatment duration, but recent studies have reported that a treatment duration of 6 months for intestinal TB is as effective as that of 9 months [5,8]. Most intestinal TB patients soon feel comfortable and symptoms usually subside in 2 weeks to 2 months after starting medication [5,6]. Moreover, Choy et al. [7] suggested that surgery should be initially withheld in intestinal TB patients with complications, as long as their lives are not at risk.

There are two notable points to emphasize regarding our case. First point is the location of TB. So far, only one case of solitary jejunal TB mimicking a tumor has been reported in Korea. Son et al. [9] reported a case of solitary small bowel TB that was misdiagnosed as small bowel cancer. There are also some reported cases of colonic TB. Colonic TB is common because the location of the ileum is adjacent to the cecum and appendix, which are vestigial lymphoid tissues. However, because of the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, not much food remains in the small intestine, which location makes difficult to be the main target of bacteria. Second point is the immunocompetancy of the patient in this case. So far, there are only two reported cases of an immunocompetent patient who acquired a TB infection in the gastrointestinal tract [9,10]. This includes the case described above [9] and a case by Chung et al. [10] who had synchronous intestinal TB involving both the stomach and distal ileum. In a review of literature, we found that 9 out of 10 articles emphasized the relationship between extrapulmonary TB and immunosuppression [2-10]. Like this case, extrapulmonary TB can occur in immunocompetent patients.

We regret that the patient would have been able to avoid surgery if endoscopy was done prior to surgery. However, on the other hand, surgery was needed in the patient who was having progressive obstructive signs and symptoms. We would like to emphasize that solitary jejunal TB can occur anywhere, even in immunocompetent patients.