진행성 악성 흑색종(Malignant Melanoma)의 새로운 내과적 치료

New Systemic Treatment for Malignant Melanoma

Article information

Trans Abstract

Although early stage melanoma can be cured by complete resection, the prognosis of the patients with unresectable or metastatic disease is dismal with the overall survival less than 1 year based on resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Dacarbazine as either a single agent or in combination regimens with other cytotoxic agents has still remained as a standard in Korea for more than three decades although it has not been associated with any survival benefit for metastatic melanoma. Recently, according to advances in molecular science and immunology, the mechanisms responsible for biology of melanoma have been elucidated and then new agents targeting these mechanisms have been introduced leading survival benefit in patients with metastatic melanoma. Unfortunately, however, it is still difficult to give those new drugs to these patients in Korea because of the health insurance guidelines still defining dacarbazine as a front line regimen and moreover high cost and unavailability in the practice. Therefore, amendment of current guidelines and an in-depth discussion with the government for the earlier use of the novel drugs are strongly needed for the patients’ sake. (Korean J Med 2013;85:357-363)

서 론

악성 흑색종(malignant melanoma)은 주로 표피의 기저층에 산재해 있는 멜라닌세포에서 발생하는 악성 종양을 말하며 멜라닌 세포가 존재하는 곳에는 어느 부위에나 발생할 수 있지만 피부에 발생하는 경우가 가장 많고 피부암 중에는 악성도가 가장 높다. 악성 흑색종은 현재 빠르게 증가하고 있는 추세이며 피부암으로 인한 사망의 65%를 차지할 정도로 악성도가 높은 종양 중의 하나로 알려져 있다[1]. 악성 흑색종의 발생 기전은 확실치 않으나 유전적 요인과 환경적 요인으로 나눌 수 있다. 원인 및 위험인자로는 인종적인 차이가 있는데 백인이 유색인종보다 발병률이 높고 자외선 노출에 의한 광 과민성, 악성 흑색종의 가족력, 멜라닌 세포성 모반, 비정형 색소모반 등이 알려져 있으며 20-50%의 흑색종은 기존의 색소모반에서 발생한다. 또한 태양열에 의한 화상이나 간헐적인 태양광 노출이 발병 위험도를 높일 수 있다[2]. 2012년에 발표된 중앙 암 등록본부 자료에 의하면 2010년에 우리나라에서는 연 202,053건의 암이 발생되었는데, 그 중 악성 흑색종이 연 428건으로 전체 암 발생의 0.2%를 차지하였다. 남녀의 성비는 0.88:1로 여자에게 더 많이 발생하였으며 연령대별로는 70대가 25%로 가장 많고 60대가 21.5%, 50대가 18.4%의 순이다.

임상적으로 흑색종이 의심되면 진단과 예후 판정을 위해 조직검사가 필수적이다. 임상적으로 의심이 되는 환자는 1-3 mm 경계를 두고 절제생검(excisional biopsy)을 시행한다. 조직학적 검사상 종양의 침윤깊이가 1 mm를 초과하거나 1 mm 미만이더라도 궤양이 있거나 mitotic rate ≥ 1 mitosis/mm2인 경우에는 감시 림프절 생검(sentinel lymph node biopsy)이 필요하다. 악성 흑색종은 조직학적으로 표재 확장성 흑색종(superficial spreading melanoma), 결절성 흑색종(nodular melanoma), 악성 흑자성 흑색종(lentigo Maligna melanoma), 말단 흑색점 흑색종(acral lentiginous melanoma)으로 분류할 수 있다. 표재 확장성 흑색종이 70% 이상을 차지하는 서구와는 달리 국내에서는 말단 흑색점 흑색종이 60% 이상 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 악성 흑색종의 예후인자로는 침윤 정도, mitotic rate, 궤양의 유무, lymphatic involvement, distant metastasis 여부 등이 있으며 이외에도 age, gender, anatomic location, pathologic factors (growth pattern, lymphatic invasion) 등도 예후에 영향을 줄 수 있다.

악성 흑색종의 치료 원칙은 조기 발견하여 충분한 수술 절제연을 두고 광범위 절제술을 시행하는 것이며 대부분은 광범위 절제술만으로 완치가 된다. 고위험군의 악성 흑색종(T4N0 and T (any)N+)의 경우 수술 후 보조 요법으로 1년간 고용량의 인터페론알파를 이용한 면역요법을 시행하는 것이 표준요법이다. 그러나 전이성 또는 완전절제를 할 수 없는 경우에는 평균 생존율이 1년 미만이며 대부분의 항암제에 내성을 보인다[3]. 과거 임상연구에서 생존율 향상의 효과를 보이지 못하였음에도 dacarbazine이 유일한 항암제로 수십년 동안 사용되어 왔으며 다른 항암제나 면역치료제와의 병합요법이 치료 반응률을 증가시키지만 생존율을 개선시키지는 못하였다[4,5]. 최근 분자생물학 및 면역학의 발달로 흑색종의 증식․진행에 관계된 다양한 signal pathway가 밝혀짐에 따라 전이성 흑색종을 가진 환자의 생존율 향상을 보인 새로운 면역치료제 및 표적치료제가 개발됨으로써 이들 환자들에서 새로운 희망과 기대를 가질 수 있게 되었다.

본 문

진행성 및 전이성 흑색종으로 수술적 접근이 어려운 경우에는 dacarbazine, paclitaxel, temozolomide 등의 항암제를 이용한 약물요법을 고려할 수 있으나 치료효과는 대부분 미미하며 악성 흑색종은 항암치료에 내성을 보이는 대표적인 질환으로 인식되었다[4,5]. 한편 CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cell(Treg)의 활성화 및 종양에서 발현되는 PD-L1과 같은 표면단백에 의한 종양세포에 대한 면역억제가 종양의 발생과 진행에 중요한 역할을 한다고 알려져 있다[6,7]. 전이성 악성 흑색종에 대한 면역치료로 고용량의 interleukin-2 (IL-2)가 16%반응율과 5-10%의 완전관해를 보고하였으며 완전관해를 보인 환자의 60%에서 장기간 재발하지 않아 1998년 미FDA의 승인을 획득하였으며 악성 흑색종의 표준치료로 사용되어왔다[8]. 그러나 고용량 IL-2는 드물지 않게 부정맥, 저혈압 등 치명적인 부작용을 동반할 수 있어 임상에서 사용하기에 제한이 많으며 IL-2는 항암제와 병합요법에서는 어떠한 임상적 이득도 보이지 않았다[9]. 최근에는 gp100 peptide vaccine과의 병용요법으로 반응률을 향상시킬 수 있다는 연구결과가 발표되었지만(RR 16% vs. 6%, p = 0.03) 생존율에는 차이를 보이지는 못하였다[10]. 그러나 분자생물학의 발달로 최근 몇 년 사이에 다양한 표적치료제가 도입되면서 전이성 악성 흑색종의 치료가 새롭게 조명되고 있다.

전이성 악성 흑색종에 대한 NCCN guideline (NCCN guideline for metastatic melanoma)

NCCN guideline은 전이성 악성 흑색종의 치료에 있어 전이부위의 완전절제 가능 여부에 따라 세분화하였으며 완전절제 가능한 전이병소의 경우 완전 절제 후 보조치료로 인터페론 알파(interferon alpha)를 투여 또는 보조치료 없이 짧은 주기로 경과관찰을 하거나 추가적인 치료에 대한 임상 연구에 참여하기를 권고하고 있다. 완전절제가 불가능한 전이성 악성 흑색종의 경우에는 ipilimumab 또는 고용량 IL-2를 사용하고 BRAF 유전자 돌연변이를 가지는 경우 vemurafenib을 사용하는 것을 표준요법으로 정의하였다. 환자나 국가적 여건상 이러한 약제의 사용이 어려운 경우 dacarbazine, temozolomide, paclitaxel의 단독 또는 병합요법을 사용할 수 있으며 c-Kit 돌연변이를 보이는 경우 imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®)을 사용해 볼 수도 있다(Fig. 1).

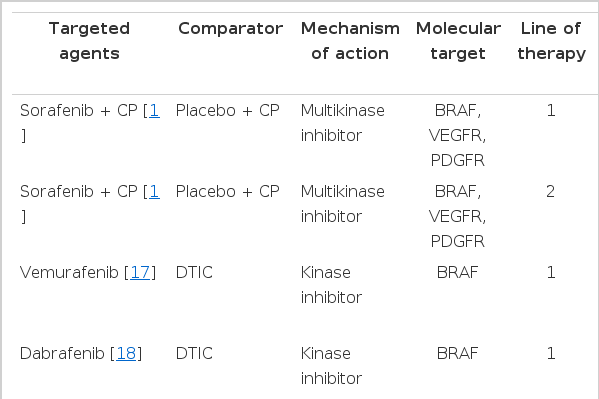

최근 개발된 표적치료제(newly developed targeted agents for metastatic melanoma)

기초과학의 발달로 흑색종의 발생과 진행에 관여하는 BRAF, NRAS 및 CKIT와 관계된 주요한 분자기전(molecular mechanism)이 밝혀졌다. 이들은 주로 MAPK 신호전달기전을 활성화시키며 NRAS 및 CKIT는 PI3K/AKT/mTOR도 활성화시킨다[11]. 또한 면역세포의 종양세포에 대한 면역회피(immune escape)에 관여하는 CTLA4, PD1, PD-L1과 같은 중요한 분자물질의 발견으로 최근 이들을 표적으로 하는 표적치료제가 다양한 임상시험을 통하여 그 효능을 입증함으로써 악성 흑색종의 치료에 새로운 역사를 이루게 되었다(Table 1).

BRAF inhibitor

BRAF 단백질은 정상세포의 증식과 생존에 관여하는 ‘MAP kinase/ERKs signaling pathway’의 중요한 구성요소로 BRAF 단백질이 활성화된 상태로 지속되게 하는 유전자 변이가 생기면 이 전달계가 과도하게 활발해져 세포의 과잉증식이 일어나게 된다. 이러한 BRAF 단백질의 유전자 변이는 전체 흑색종의 절반 그리고 고형 종양 전체의 8% 정도에서 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다.

BRAF를 포함하여 다양한 tyrosine kinase를 차단하는 약제인 sorafenib은 1상 및 2상에서 무진행 생존율을 향상시킴을 보고하여 악성 흑색종의 새로운 치료제로 기대를 모았다[12-14]. 그러나 phase III randomized controlled trial (RCT)에서는 1차 또는 2차 약제로 항암제(paclitaxel + carboplatin)와 함께 사용하였을 때 어떠한 임상적 효과도 보이지 못하였다[15,16]. 이후에 개발된 Vemurafenib (Zelboraf®)은 BRAF specific inhibitor로 BRAF V600E 변이가 확인된, 수술이 불가능하거나 전이성인 흑색종 환자를 위한 단독 요법으로 사용된다. 기존의 dacarbazine과 비교한 Phase III RCT에서 반응률이 48% vs. 5%, 전체 생존율이 13.2 vs. 9.6개월(HR = 0.37; 95%CI = 0.26-0.55; p < 0.001) 및 6개월 생존율이 84% vs. 64%로 vemurafenib군에서 유의하게 향상됨을 보여주었다[17]. 가장 흔하게 관찰된 3등급 이상반응들은 피부부작용과 관련이 있었으며 그 중에는 피부 편평상피세포암(squamous cell carcinoma)도 포함되어 있었다. 더불어 일부 환자들 사이에서는 간 효소 수치가 대체로 경미하면서 회복 가능한 수준으로 증가하는 현상이 관찰되었다. 가장 많이 보고된 Vemurafenib의 이상반응으로는 관절통, 피로감, 발진, 광 과민반응, 구토, 탈모, 가려움증 등이 있었다[17]. 또 다른 BRAF inhibitor인 Dabrafenib(TafinlarⓇ)은 기존의 항암치료인 dacarbazine과 비교한 3상 연구(BREAK study)에서 250명의 BRAF V600E 전이성 흑색종 환자를 대상으로 dabrafenib 군에서 의미 있게 무진행 생존율(progression free survival, PFS)을 향상시킨다는 것이 보고되었다(PFS 5.1 vs. 2.7 months; p < 0.0001) [18]. 3등급 이상의 이상반응으로는 피부 편평상피세포암, 발열, 신부전, 고혈당 등이 보고되었으며 가장 흔한 이상반응으로는 두통, 관절통, 탈모, 수족증후군 등이 있었다.

MEK inhibitor

Trametinib (Mekinist®)은 강력한 MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor이다. Phase III RCT에서 BRAF V600E/K 변이가 있는 진행성 혹은 전이성 흑색종 환자에서 기존의 항암치료제인 dacarbazine(1,000 mg/m2) 혹은 paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) 3주요법과 비교하여 유의하게 생존율을 향상시킴을 보여주었다(HR 0.47 95% CI: 0.34-0.65; p < 0.0001) [19]. 가장 많이 보고된 trametinib의 이상반응으로는 발진, 설사, 부종 등이 있었다. BRAF inhibitor에서 관찰될 수 있는 심각한 부작용중의 하나인 피부 편평상피세포암은 보고되지 않았다. BRAF inhibitor의 약제 내성 기전의 하나로 MAPK pathway의 reactivation이 있다. 그러므로 BRAF의 downstream pathway인 MEK을 같이 차단함으로써 약제 저항성의 지연을 기대해 볼 수 있다. 이에 근거하여 BRAF inhibitor인 dabrafenib과 MEK inhibitor인 trametinib을 병용 투여하는 phase I/II trial이 시행되었다[20]. 이 연구에서 dabrafenib 단독요법에 비해 병용요법을 시행한 군에서 무진행 생존기간이 4개월 이상 지연되었고, 발열 이외에 부작용의 증가는 관찰되지 않았다.

Anti-CTLA4 antibodies

Ipilimumab (Yervoy®)은 T 세포가 발현하는 CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4)의 inhibitory signal을 억제하여 T-cell을 활성화시키는 역할을 한다. IL-2 치료에 실패한 진행성 및 전이성 악성 흑색종 환자를 대상으로 한 Phase III RCT에서 ipilimumab 단독 또는 gp100 vaccine 병합치료가 gp100 vaccine 단독치료에 비하여 사망률을 각각 34%, 32% 감소시킴을 확인하였다. 또한 치료받지 않은 흑색종 환자를 대상으로 dacarbazine과 병용한 Phase III RCT에서 dacarbazine 단독군에 비하여 중앙생존기간이 11.2 vs. 9.1개월로 ipilimumab + dacarbazine 병용군에서 유의하게 향상됨을 보여주었다(HR 0.72, p < 0.001) [22]. 이에 미 FDA에서는 전이성 악성 흑색종의 1차 치료로서 ipilimumab+DTIC를 ipilimumab 단독요법을 2차 치료로 2011년 승인하였고 유럽에서도 2차 치료로서 ipilimumab을 승인하였다. 또 다른 anti-CTLA4 항체인 tremelimumab은 제2상 임상연구에서 9% 반응률과 29-33%의 6개월 무진행률 보고하였으나 DTIC 또는 temozolomide와 비고한 제3상 임상연구에서 표준항암치료군에 비하여 무진행생존율은 의미 있게 높았으나 전체 생존율의 차이를 보이지는 못하였다(12.6 vs. 10.7; HR = 0.88; p = 0.127) [23]. 그러나 본 연구에서는 ipilimumab 연구와 달리 3개월 간격으로 투여하여 상대적으로 효과가 낮았고 임상에서 ipilimumab이 사용 가능해짐에 따라 control 군의 피험자들의 16%가 병의 진행 후 ipilimumab을 투여받았기 때문에 전체 생존율의 차이를 보이지 못했을 가능성이 있다.

Anti-PD1 및 anti-PD-L1 antibodies

PD1은 활성화된 T 세포에 발현되며 종양세포에 대한 면역도피(immune escape)에 관여하고 PD-L1 또한 종양 및 종 양주위 다양한 세포에서 발현되어 면역도피를 촉진시킨다. 특히 anti-PD1 antibody는 135명의 진행성 악성 흑색종 환자에 투여하여 38%의 반응률을 보였으며 치료 반응이 있었던 환자의 81%에서 11개월 이상 효과가 유지되었다[24]. 현재 다양한 anti-PD1 및 PD-L1 inhibitor가 개발되었으며 아직 대규모 3상 연구 결과는 없으나 추후의 임상결과를 주목할 필요가 있다.

Targeted agents for melanoma with c-kit mutation

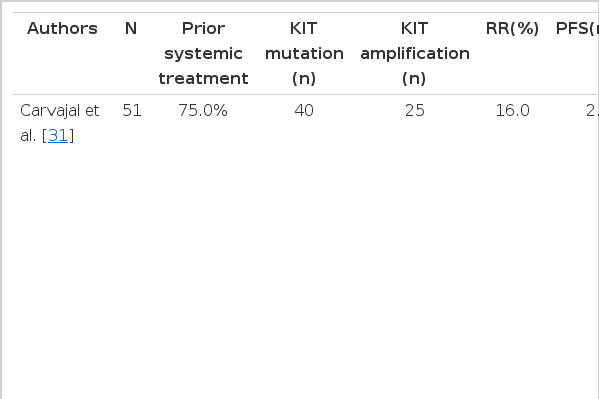

국내에서 호발하는 mucosal 혹은 acral melanoma에서는 KIT mutation이 약 10-20%에서 detection 된다고 알려져 있다. KIT는 type III transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase로 ligand가 KIT 수용체에 결합하게 되면 세포 내 signaling pathway를 활성화시켜 종양세포의 성장, 증식, 침윤, 전이에 관여한다[25]. 또한 KIT 연관 pathway는 정상 melanocyte의 발현에도 관여를 하는 것이 잘 알려져 있다[26,27]. 악성 흑색종에서는 KIT gene amplification 또는 활성화 돌연변이(activating mutation)이 드물지 않게 확인되어 KIT 유전자 변이를 보이는 악성 흑색종의 새로운 표적으로 생각하게 되었다. 그러나 KIT를 포함한 다수의 tyrosine kinase를 차단할 수 있는 imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®)을 이용한 초기의 임상연구에서는 전이성 악성 흑색종에 대하여 의미 있는 효과를 확인할 수 없었으나[28-30] 이들 연구에서는 KIT mutation이나 amplification을 가진 종양만을 선택하지 않은 한계가 있다. 최근의 Phase II 임상연구에서는 imatinib mesylate가 KIT mutation이 있는 전이성 악성 흑색종에서 두드러진 효과를 보임을 확인하였으며, GIST 임상연구에서와 같이 악성 흑색종에 있어서도 V654A, D820Y mutation을 가지는 종양의 경우 imatinib에 내성을 보이므로 이러한 imatinib-저항성 KIT mutation을 제외한 환자를 대상으로 한 Phase III 임상연구가 imatinib의 효과를 증명해 줄 것으로 기대할 수 있다(Table 2) [31,32].

결 론

현재까지의 결과를 종합해 볼 때 악성 흑색종의 치료는 근치적 절제이다. 수술적 치료가 불가능한 전이성 흑색종의 경우 최근 다양한 표적치료제 및 면역요법의 임상 결과가 발표되면서 생존율의 향상을 가져왔다. 최근의 분자생물학의 발전으로 악성 흑색종을 분자생물학적․유전적 특성에 따라 세분화하여 이에 따른 적절한 표적치료제의 사용으로 이제까지 예후가 아주 불량한 것으로 여겨왔던 악성 흑색종에서도 환자의 생명연장을 기대할 수 있게 되었다. 다만 국내에서는 dacarbazine 단독 또는 병합요법이 여전히 1차 약제로 규정하고 있으며 새로이 개발된 표적치료제가 국내에 시판되어 있지 않거나 고가이어서 임상에서 사용하는 데 여전히 제한점이 많이 있다. 최근의 대규모 3상 임상시험 결과를 바탕으로 한 국내 보험 규정의 수정과 의료행정을 담당하는 정부부처와의 긴밀한 토의를 통하여 가능한 빠른 시일 안에 흑색종 환자들이 치료의 혜택을 받을 수 있도록 하는 노력이 절실히 필요하다.