급성 흉통의 평가 및 감별 진단

Evaluation and Diagnosis of Acute Chest Pain

Article information

Trans Abstract

Acute chest pain is a frequent cause of visits to emergency departments. As the major etiologies of such pain include life-threatening acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism, prompt diagnosis and management are essential. After exclusion of coronary artery disease, other cardiac causes must be considered. In this review, we discuss the diagnosis of acute chest pain with a focus on clinical symptoms and the initial examination.

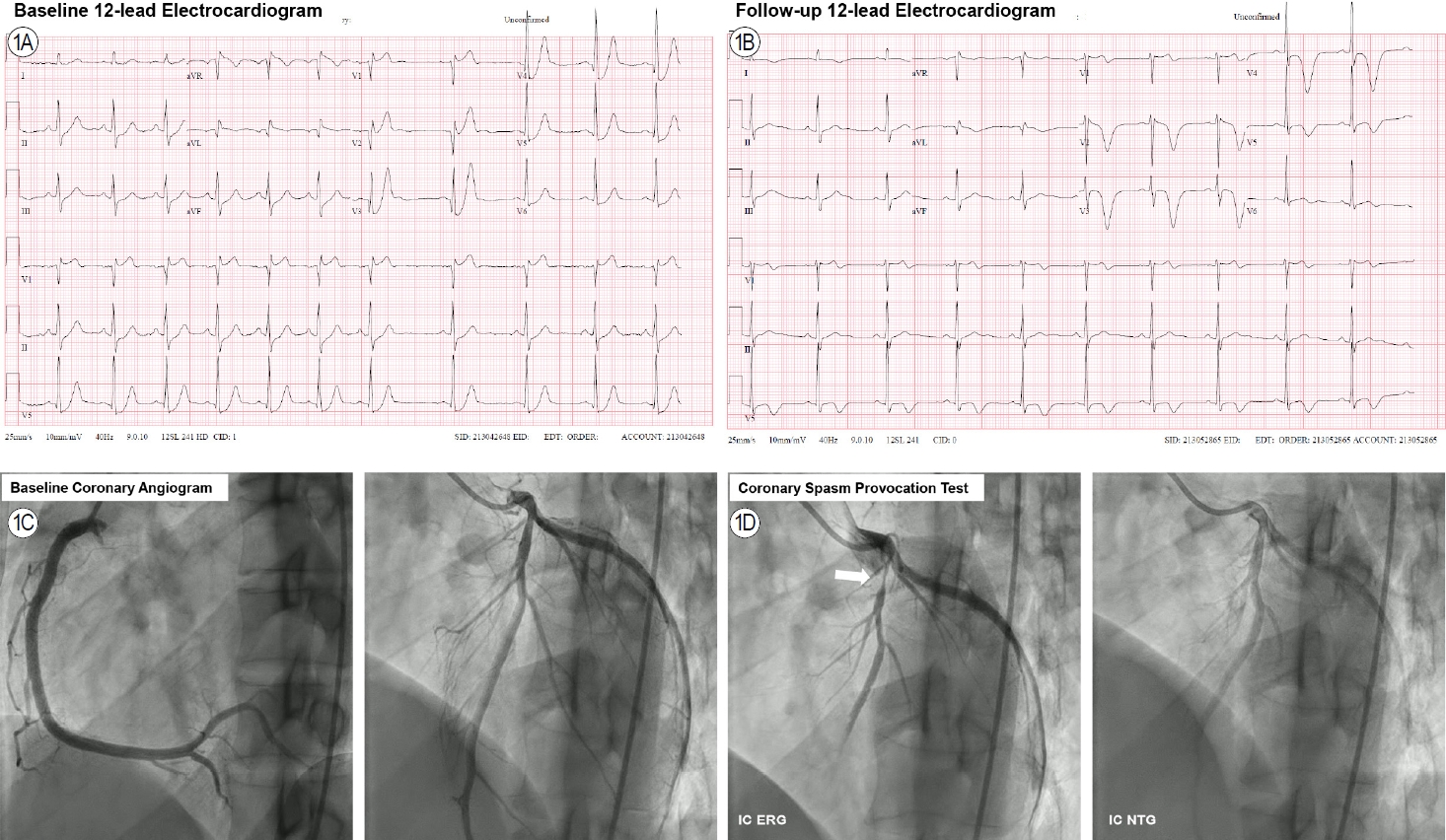

증례 1: 32세 남자가 내원 1시간 전부터 지속되는 흉통으로 새벽 6시경 응급실에 내원하였다. 흉통의 양상은 좌측 흉부에 압박감(pressure)이 지속되면서 양측 팔로 방사(radiation)되었고 식은땀(diaphoresis)을 동반하는 상태로, 응급실 내원 후 설하니트로글리세린(nitroglycerin)을 투여받은 후 1-2분 내 증상이 호전되었다. 환자는 흡연자로 10갑년의 흡연력을 가지고 있었으며, 사회적 음주자(social drinker)로 내원 1일 전 음주를 하였다. 내원 당시 활력 징후는 혈압 118/70 mmHg, 맥박 70회/분, 호흡 18회/분, 체온 36.8℃였다. 혈액 검사에서는 백혈구 9,500/mm3, C-반응 단백(C-reactive protein, CRP) 0.19 mg/dL, 고민감도 트로포닌-T (high-sensitivity troponin-T, HS Tn-T) 0.008 ng/mL, 심장형 크레아틴키나제(creatine kinase myocardial band, CK-MB) 2.55 ng/mL로 정상 범위로 확인되었다. 표준 12유도 심전도(electrocardiogram, ECG) 상에서 초기에 V2-6 유도의 저명한 ST분절의 변화가 관찰되었으며, 1시간 후 시행한 추적 ECG 검사상에서 V2-6 유도의 큰 T파 역위로의 역동적인 변화가 관찰되었다(Fig. 1). 정규(elective) 관상동맥 조영술(coronary angiography, CAG) 상에서는 좌관상동맥 및 우관상동맥에서 유의한 협착 소견이 관찰되지 않았다. 관상동맥 연축 유발 검사(coronary spasm provocation test)를 이어서 시행하였고, 관상동맥 내 에르고노빈(ergonovine)을 투여한 후 좌전하행지(left anterior descending artery, LAD) 근위부의 아전하(subtotal) 폐색이 유발되면서 관상동맥 내 혈류 저하 소견이 함께 관찰되었다(Fig. 1). 당시 환자는 응급실 내원 시와 유사한 흉통을 호소하였고, ECG 상 전흉부유도(V1-4)의 ST분절 상승 및 T파 역위가 함께 관찰되었다. 관상동맥 내 니트로글리세린을 투여한 후 기저 상태로 혈관 내경이 확장되면서 혈류가 개선되었고 환자의 증상 역시 호전되었다. 본 환자는 혈관연축성 협심증(변이형 또는 이형성 협심증)으로 진단하였고 칼슘채널차단제 등의 혈관 확장제를 투여하였다.

A 32-year-old male with chest pain. (A) Significant ST-segment depression was apparent in the baseline 12-lead electrocardiogram. (B) A follow-up electrocardiogram revealed dynamic deep T-wave inversion changes in the precordial leads. (C) The baseline coronary angiogram evidenced insignificant stenosis of both coronary arteries. (D) After intracoronary ergonovine administration, a subtotal vasospasm developed in the proximal left anterior descending artery (arrow) but was completely relieved by intracoronary nitroglycerine. ERG, ergonovine; IC, intracoronary; NTG, nitroglycerine.

증례 2: 87세 여자가 내원 1일 전부터 지속되는 흉통으로 응급실에 내원하였다. 흉통의 양상은 전흉부에 묵직한 느낌(heaviness)이 지속되면서 호흡곤란이 동반되었다. 환자는 지속적으로 고혈압 치료를 위한 약물을 복용 중이었고, 내원 13년 전 LAD에 관상동맥 스텐트 삽입술을 시행받은 후 단독 항혈소판제 요법(클로피도그렐 75 mg/day)을 유지 중이었다. 내원 2일 전 COVID-19 백신을 접종한 기왕력이 있었다. 환자는 백신 접종 이후 지속적인 전신쇠약, 피로, 근육통에 따른 수면 부족 등 비특이적인 증상을 함께 호소하였다. 내원 당시 활력 징후는 혈압 135/78 mmHg, 맥박 66회/분, 호흡 20회/분, 체온 37.0℃였다. 혈액 검사에서는 백혈구 8,500/mm3, CRP 0.34 mg/dL, HS Tn-T 0.506 ng/mL, CK-MB 11.39 ng/mL로 심근효소가 저명하게 상승되어 있었다. 12유도 ECG 상에서 우각차단 소견과 함께 V3 유도 및 V4-6 유도의 ST분절 상승과 V2-3 유도의 upright T파가 관찰되고 있다(Fig. 2). 응급(emergent) CAG 상에서 유의한 협착 소견이 관찰되지 않았다. 좌심실 조영술(left ventriculogram)에서 특징적인 좌심실 심첨부(apex)의 운동장애가 관찰되고 있었으며 좌심실 확장기 말압(left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, LVEDP)이 23 mmHg로 상승되어 있었다(Fig. 2). 정규 심장초음파 상에서도 좌심실 심첨부의 국소 벽 운동장애와 함께 경미한 좌심실 구혈률 감소(left ventricular ejection fraction, 42.3%)가 관찰되었다. 이상의 소견을 바탕으로 본 환자는 스트레스성 심근병증(stress induced cardiomyopathy)으로 진단되어 심부전 약물 치료를 시행받았다.

An 87-year-old female with chest pain. (A) A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed a right bundle branch block with an anterolateral ischemic pattern presenting as slight ST-segment elevation in lead V3, slightly more in leads V4-6, and upright T-waves in leads V2 and V3. (B) A coronary angiogram evidenced insignificant stenosis of both coronary arteries. (C) A left ventriculogram revealed akinesia of the apex (an apical ballooning pattern) during the systolic phase (arrows).

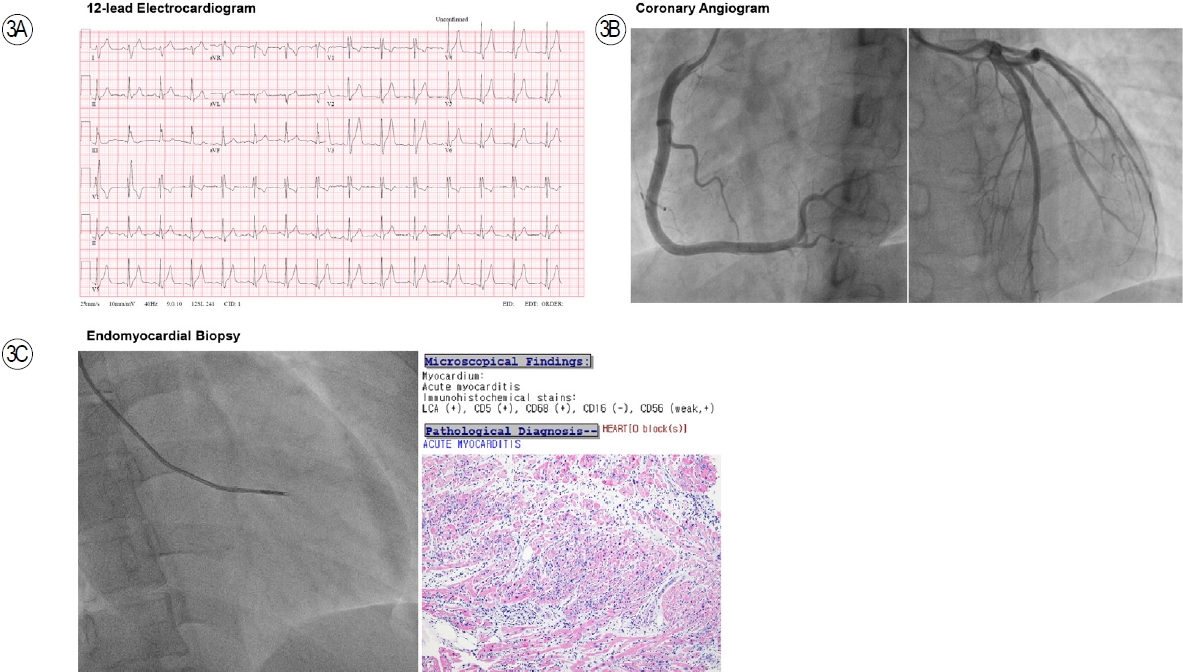

증례 3: 22세 남자가 내원 2일 전부터 지속되는 흉통으로 응급실에 내원하였다. 흉통의 양상은 전흉부에 묵직한 느낌(heaviness)이 지속되면서 호흡곤란이 동반되었다. 환자는 흡연자로 8갑년의 흡연력이 있었다. 내원 5일 전 COVID-19 백신을 접종한 기왕력이 있었다. 내원 당시 활력 징후는 혈압 100/70 mmHg, 맥박 95회/분, 호흡 22회/분, 체온 37.8℃였다. 혈액 검사에서는 백혈구 14,500/mm3, CRP 3.51 mg/dL, HS Tn-T 14.164 ng/mL, CK-MB 34.19 ng/mL로 심근효소가 저명하게 상승되어 있었다. ECG 상에서 전흉부유도(V2-6)의 ST분절 상승이 관찰되었다(Fig. 3). Emergent CAG 상에서 유의한 협착 소견이 관찰되지 않았다. 이후 심장조직 검사(endomyocardial biopsy)를 시행하였으며, 검사 결과 급성 심근염(acute myocarditis)으로 진단되었다(Fig. 3).

A 22-year-old male with chest pain. (A) A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed diffuse ST-segment elevations in the precordial leads. (B) A coronary angiogram evidenced insignificant stenosis of both coronary arteries. (C) An endomyocardial biopsy was performed, and the pathological findings were compatible with acute myocarditis.

본 론

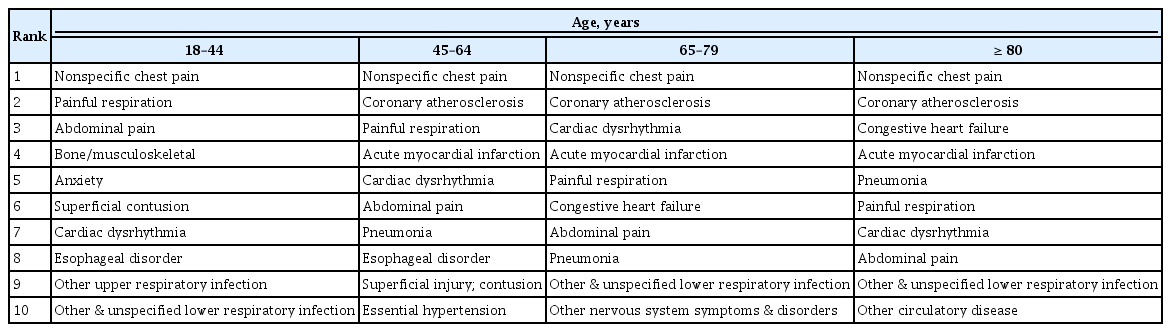

급성 흉통(acute chest pain)은 환자들이 병원을 찾는 가장 흔한 원인 중의 하나이다. 흉통 또는 가슴 통증은 환자뿐 아니라 의료진도 흔하게 사용하는 용어로 보통 앞 가슴의 불편하고 불쾌한 느낌을 포괄적으로 가리킨다. 급성 흉통을 호소하는 환자들에게는 가장 중요한 생명을 위협하는 원인 중 하나인 심혈관계 문제(cardiovascular problem)에 대한 고려가 필요하며, 특히 급성 심근경색증(acute myocardial infarction)에 대한 감별 진단이 선행되어야 한다[1]. 하지만 실제로 심혈관계 문제 외에도 다양한 원인들이 급성 흉통을 유발할 수 있기 때문에 환자의 연령에 따라 다른 비심장성(non-cardiac)원인들도 함께 고려되어야 한다(Table 1) [2]. 급성 흉통의 원인에 따라 치료나 환자의 예후가 달라지기 때문에 흉통을 정확하게 감별하여 진단하는 것은 무엇보다 중요하다.

본 논문에서는 실제 임상에서 경험하게 되는 급성 흉통의 다양한 원인을 증례 위주로 살펴보고 진단적 접근에 대하여 알아보고자 한다.

증상 양상에 따른 고려 사항

급성 흉통에 대한 진단적 접근의 시작은 자세한 병력 청취로부터 시작되는데, 무엇보다 흉통의 양상이 전형적(typical)인 심근 허혈성 통증인지 감별하는 것이 중요하다[3]. 다른 장기와 마찬가지로 심근 허혈에 의한 통증은 특징적으로 심부(deep)에서 느껴지고, 보통 미만성(diffuse)이므로 아픈 부위를 특정할(localize) 수 없다. 따라서, 환자가 호소하는 증상 양상에 따라 심근 허혈성 통증의 가능성을 짐작해 볼 수 있다. 예를 들어, 흉통의 양상이 “날카롭다(sharp)”, “옮겨 다닌다(shifting)”, “호흡에 따라 아프다(pleuritic)”, “자세의 변화로 통증이 유발된다(positional)” 등이라면 심근 허혈성 통증일 가능성이 낮다고 할 수 있다. 반대로 만약 흉통의 양상이 “압박한다(pressure)”, “묵직하다(heaviness)”, “쥐어짠다(squeezing or thightness)”, “움켜쥔다(gripping)” 등이라면 심근 허혈성 통증일 가능성이 높다고 할 수 있다. 그 밖에도 흉통의 지속 시간, 유발 또는 완화 요인, 환자의 연령, 심혈관질환 위험 인자 및 과거력 등이 진단적 접근 과정에서 반드시 고려되어야 한다. 이러한 흉통의 양상과 임상적 요소들을 고려하여 급성 심근경색증을 예측하는 flow diagram이 제시되기도 하나 실용적이지 않다는 제한점이 있다[4]. 한편, 심근 허혈성 통증의 가장 흔하고 중요한 원인은 관상동맥 질환(coronary artery disease, CAD)에 따른 급성 관상동맥 증후군(acute coronary syndrome)이지만, 심근 허혈을 야기하는 여러 다양한 질환의 가능성도 항상 염두에 두어야 한다.

우선순위에 따른 급성 흉통의 감별 진단

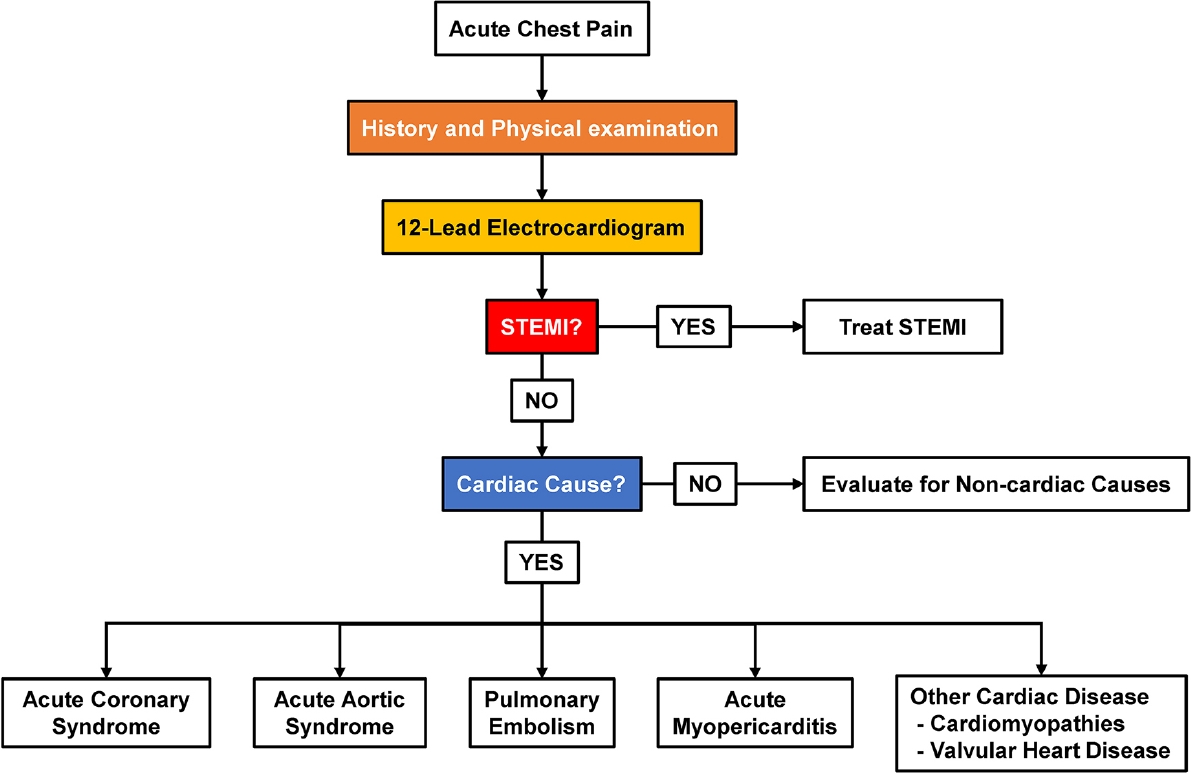

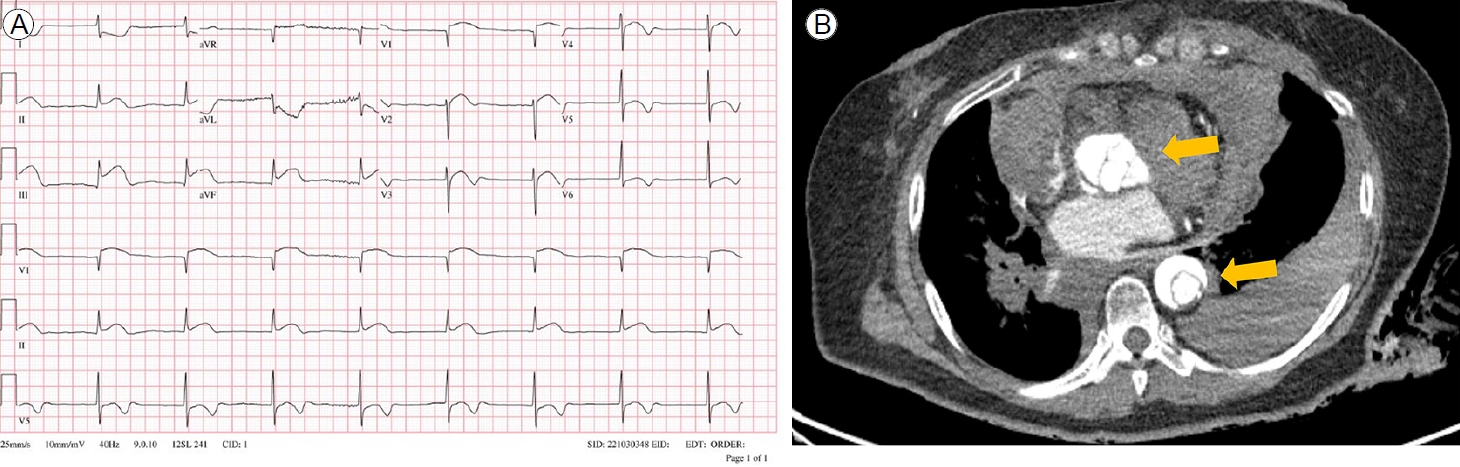

응급실에서 급성 흉통에 대한 병력 청취와 함께 반드시 고려해야 할 사안은 진단의 우선순위(priority)이다. 즉, 즉각적인 진단과 치료가 이뤄지지 않을 경우 환자의 생명을 위협하거나 중대한 손상을 야기할 수 있는 초응급 질환들에 대한 감별을 우선 고려해야 한다는 것이다. 대표적인 질환으로는 급성 심근경색증(myocardial infarction), 대동맥 박리(aortic dissection), 폐동맥 색전(pulmonary embolism) 등이 있다. 병원에 따라 이들 세 질환을 동시에 감별할 수 있는 프로토콜(protocol)을 사용하는 컴퓨터단층촬영(computed tomography, CT)이 가능하기도 하나 모든 병원에서 가능하지 않다는 것이 현실이다. 뿐만 아니라, 응급 CT 촬영을 위하여 조영제 투여가 가능한지 여부를 신장 기능(renal function)으로 신속하게 확인할 수 있는 현장진단 검사(point of care testing, POCT) 역시 모든 병원에서 사용 가능하지 않다. 이러한 의료 환경에서 가장 초기 검사 중 하나인 ECG 소견은 일견 간편하지만 중요한 검사라고 할 수 있다. ECG 소견을 통하여 일차적으로 ST분절 상승 급성 심근경색증에 대한 감별이 가능하며, ECG 소견이 특징적이지 않다면 다른 응급 질환을 염두에 두고 환자 중심으로 접근을 하여야 한다(Fig. 4). 예를 들면, 환자가 말판 증후군(Marfan syndrome) 등으로 대표되는 결합조직 질환(connective tissue disorder)의 과거력이 있거나, 갑작스럽게 발생한 심한 통증, 사지 맥박이 서로 다른 경우(환자의 약 30%), 흉부 X선상 종격동(mediastinum)의 확장이 관찰된 경우, 실신, 대동맥판 역류가 동반된 경우 등은 대동맥 박리를 우선 고려해 볼 수 있다[5,6]. 폐동맥 색전의 경우 특징적인 심전도 소견(S1Q3T3)이 관찰되거나, 빈맥, 호흡 곤란, 흡기 시 통증이 동반될 경우 우선적으로 의심해 볼 수 있다[7]. 또한 하나의 질환이 아니라 두 가지 질환이 동시에 발생하여 진단을 더 어렵게 만들고 환자의 치료가 지연되는 사례가 발생할 수 있음을 반드시 명심하여야 한다(Fig. 5).

Acute myocardial infarction caused by aortic dissection. (A) A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed significant ST-segment elevations in the inferior leads and ST depressions in the lateral leads of V4-6. (B) Computed tomography angiography of the chest showed a Stanford type A aortic dissection involving both the ascending and descending aortae (arrows). Large pericardial and right pleural effusions were also observed.

관상동맥 질환 외의 심장성 급성 흉통의 감별 진단

환자가 호소하는 급성 흉통이 병력 청취와 신체 진찰 및 초기 심전도 검사에서 심장 원인에 의한 증상으로 판단된다면, 우선적으로 CAD 유무에 대한 감별이 이루어져야 할 것이다. CAD는 응급실에서 접하게 되는 급성 흉통의 가장 흔한 원인인 동시에 진단이 지연되는 경우 환자에게 치명적일 수 있기 때문이다. 하지만 앞서 언급한 바와 같이 심근 허혈성 통증은 CAD 외에 다양한 원인에 의해 유발될 수 있으므로, CAG 등을 통하여 CAD가 배제되면 반드시 다른 가능성을 염두해야 한다.

증례 1의 경우 환자가 전형적인 심근 허혈성 통증 양상을 호소하였고, ECG 상 저명한 ST분절의 상승이 관찰되지는 않았지만 ST분절의 하강 및 T파 역위 등 역동적인 변화를 보이고 있었다. 환자의 음주력, 새벽에 발생한 흉통, 설하 니트로글리세린에 증상이 완화된 점 등을 고려하였을 때 관상동맥 연축에 의한 증상일 가능성이 반드시 고려되어야 한다. 증례 2는 고령의 환자이고 오래전 관상동맥 스텐트 삽입술을 시행받았으며 ECG 상 ST분절 및 T파 변화가 관찰되어 우선적으로 CAD 감별이 필요하다고 할 수 있다. 하지만 동시에 스트레스에 취약한 고령의 여성 환자가 최근 COVID-19 백신 접종을 받은 후 통증을 호소하였기 때문에, 스트레스성 심근병증 및 급성 심근염의 가능성 역시 염두에 두어야 한다. 환자는 발열 증상이 없었고 백혈구 및 CRP 수치도 정상이었기 때문에 임상적으로는 스트레스성 심근병증의 가능성이 더 높을 것으로 판단할 수 있었다. 반대로 증례 3은 특별한 기저 질환이 없었던 건강한 남성 환자가 최근 COVID-19 백신 접종 후 발열, 백혈구 및 CRP 수치의 상승을 동반한 흉통과 ECG 상 ST분절의 상승이 관찰되었기 때문에 급성 심근염을 우선적으로 고려할 수 있었다.

병력 청취와 신체 진찰, ECG, 흉부 X선, 혈액 검사 등의 기본 검사 외에 급성 흉통의 감별 진단에 많은 도움이 되는 또 다른 진단적 도구로는 심장 초음파(echocardiography)가 있다[8]. 심장 초음파 검사를 통해 좌심실 및 우심실 기능, 국소 벽 운동장애, 대동맥 등 심장 및 주요 혈관 구조와 기능에 대한 평가가 가능하고, 주요한 초응급 질환(심근경색증, 대동맥 박리, 폐동맥 색전)을 신속하게 감별할 수 있다[9]. 응급실에서 심장 초음파 검사가 가능한 경우에는 정확한 진단을 위한 많은 단서를 제공하여 임상적 불확실성을 줄일 수 있으므로 침습적 검사를 시행하기에 앞서 적극적으로 사용을 고려해야 할 것이다.

결 론

급성 흉통을 호소하는 환자에서 우선적으로 고려되어야 할 사항은 자세한 병력 청취와 신체 진찰을 통하여 환자의 증상이 심혈관계 원인에 의한 것인지를 확인하는 것이다. 전형적 심근 허혈성 증상을 호소하는 환자라면 급성 심근경색증, 대동맥 박리, 폐동맥 색전 등 환자의 생명을 위협하는 초응급 질환에 대하여 우선순위를 두고 신속한 진단이 이루어져야 할 것이며, 정확한 진단을 바탕으로 시기적절한 치료가 시행되어야 환자의 생명을 구할 수 있다. 만약 초응급 질환이 배제되었다면 비교적 흔하게 급성 흉통을 유발하는 관상동맥 질환 가능성을 반드시 염두에 두고, 동시에 환자 중심적 접근법으로 다른 응급 질환의 가능성을 생각하고 진단을 위한 추가적인 검사를 고려해야 한다.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: LSH, HYJ

Acquisition of data: LSH

Analysis and interpretation of data: LSH, KMC

Drafting of the manuscript: LSH

Critical revision for intellectual contents: LSH, KMC, SDS, HYJ, KJH, AY, JMH

Final approval of the manuscript: LSH, KMC, SDS, HYJ, KJH, AY, JMH

Acknowledgements

None.