헬리코박터 파일로리 감염의 진단 및 내시경 소견

Endoscopic Features According to Helicobacter pylori Infection Status

Article information

Trans Abstract

It is important to evaluate Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection based on endoscopic results because numerous studies have shown a link between H. pylori infection and upper gastrointestinal conditions, such as gastric cancer. The association between H. pylori infection and gastritis is fully described in the Kyoto classification of gastritis. Typical endoscopic findings in the absence of H. pylori infection are a regular arrangement of collecting venules, fundic gland polyps, red streaks, and other similar features. By contrast, typical endoscopic findings in individuals with active H. pylori infection include diffuse mucosal erythema, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, inflated or tortuous folds, discharge of sticky mucus, mucosal nodularity, foveolar hyperplastic polyps, and/or xanthomas. Patchy mucosal redness and map-like mucosal redness are typical endoscopic findings in previously infected people. Because of its straightforward application in standard clinical practice, this categorization can reflect the risk of stomach cancer and be useful for both primary care physicians and experienced endoscopists.

서 론

헬리코박터 파일로리(Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori)는 40년 전 처음 그 존재가 알려진 이후로 소화성 궤양, 위점막 연관 림프종, 위암 등 다양한 위장 질환과 연관이 있다는 것이 밝혀졌고[1-4], 특히 위암과의 연관성이 증명되어 세계보건기구에서는 H. pylori를 제1군 발암물질로 규정하였다[5]. 이에 위암을 유발하는 H. pylori 감염의 정확한 진단이 이전보다 중요한 의미를 가지게 되면서 H. pylori를 진단하기 위한 검사 방법들이 개발되었고, 최근에는 내시경 검사 여부에 따라 비침습적 검사 방법과 침습적 검사 방법으로 나누어 임상에서 시행되고 있다. 내시경을 시행하지 않는 비침습적 방법에는 요소 호기 검사, 대변 항원 검사, 혈청 IgG 항체 검사가 있고, 침습적 검사 방법에는 급속 요소분해효소 검사, 조직 검사, 배양 검사 등이 있다. 그러나 혈청 검사는 제균 치료를 받더라도 수년 동안 양성으로 나타날 수 있기 때문에 현재의 활동성 감염과 과거의 감염을 구분하기 어렵고[6,7], 요소 호기 검사 및 급속 요소분해효소 검사는 항생제 또는 양성자펌프억제제를 사용 중인 환자나 위장관 출혈이 있는 환자 및 순응도가 떨어지는 환자에서는 검사의 정확도가 떨어질 수 있다[8,9].

최근 내시경 기기의 해상도가 좋아지고 기술이 발전하면서 narrow-band imaging (NBI), 영상 강화 내시경(image-enhanced endoscopy) 등을 통해 위점막 및 혈관상의 세밀한 부분까지 관찰하고 분류하는 것이 가능해졌고, 이를 이용하여 H. pylori의 미감염(naïve), 현감염(infected) 혹은 기감염(eradicated states)과 위점막의 특정 소견과의 연관성에 대해 다양한 연구들이 진행 중이다[10-13]. 이에 여러 가지 검사들을 통해서 진단했던 H. pylori의 감염 소견을 내시경 사진만으로 예측할 수 있게 되었고, 2013년 H. pylori 감염 상태와 위암에 대한 위험성을 채점하는 위염의 Kyoto 분류(Kyoto classification of gastritis and gastric cancer)가 제안되면서 기존의 H. pylori 관련 위염에 대한 여러 연구들이 객관화되었다. 그리고 위점막 상태를 내시경적 소견에 따라 H. pylori 미감염 점막(nongastritis), H. pylori 현감염 점막(active gastritis)과 H. pylori 기감염(inactive gastritis) 점막으로 분류할 수 있게 되었다[11,14,15].

본 론

H. pylori 감염 여부에 따른 내시경 소견

Kyoto 분류에 따르면 위점막을 다음과 같은 객관적인 내시경 소견으로 나타낼 수 있다[11]: 1) 위축(atrophy), 2) 선와상피-과형성성 용종(foveolar-hyperplastic polyp), 3) 황색종(xanthoma), 4) 장상피화생(intestinal metaplasia), 5) 점상 발적(spotty redness), 6) 결절성 변화(nodularity), 7) 미만성 발적(diffuse redness), 8) 점막 부종(mucosal swelling), 9) 위체부 주름의 종대(enlarged fold), 10) 반상 발적(patchy redness), 11) 융기형 미란(raised erosion), 12) 헤마틴(hematin), 13) 선상 발적(red streak), 14) 다발성의 백색 편평 융기(multiple white and flat elevated lesions), 15) 지도상 발적(map-like redness), 16) 위저선 용종(fundic gland polyp), 17) 균일한 혈관상(regular arrangement of collecting venules, RAC). 위의 소견들을 이용하여 H. pylori 감염 상태를 미감염, 현감염, 기감염 상태로 분류할 수 있다.

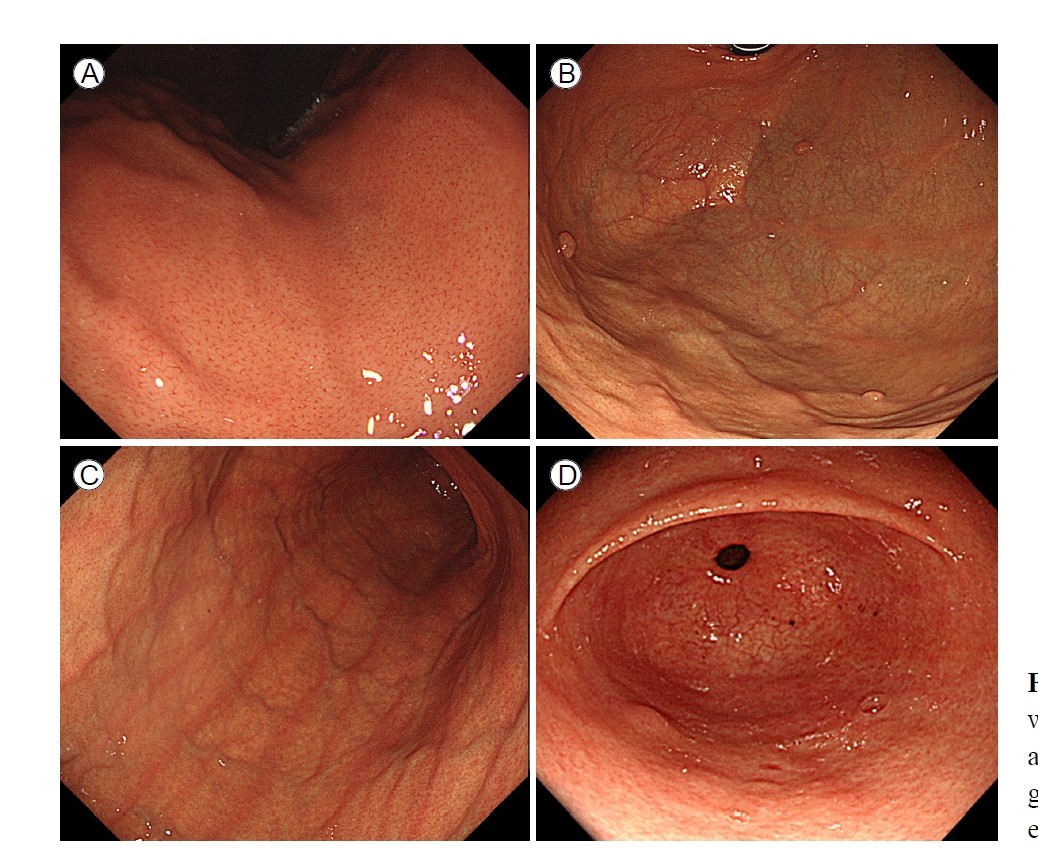

H. pylori 미감염 내시경 소견

H. pylori에 감염된 적이 없는 위의 위저선 점막에는 규칙적으로 배열하는 새 발자국 모양의 미세한 붉은 혈관상들이 관찰되는데, 이를 균일한 혈관상이라고 한다. 일반적으로 위저선 점막에 보이는 선관 구조의 배열과 주위에 분포하는 미세 혈관들은 벌집 모양 구조를 형성하고 있는데, 이러한 혈관들이 융합되면 집합 세정맥(collecting venule)이 되고, 이는 점막 하층의 정맥으로 이어진다. 집합 세정맥이 점막에 투영되는 형태가 균일한 혈관상으로, 이렇게 전정부 근위부와 위체부에서 균일한 혈관상이 관찰되면 H. pylori 미감염의 높은 민감도, 특이도를 보이며, 90% 이상의 음성 예측률을 나타낸다[10,11].

하지만 균일한 혈관상은 H. pylori 감염이 없어도 나이가 증가함에 따라 희미해질 수 있기 때문에 내시경 소견 해석에 주의를 기울여야 한다[16,17]. 그 외에 H. pylori 미감염과 관련된 내시경 소견으로는 위저선 용종, 헤마틴, 선상 발적, 융기형 미란 등이 있다[11]. 하지만 융기형 미란은 H. pylori 감염과도 연관이 있다고 밝혀진 바 있으며, H. pylori 감염뿐 아니라 non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 복용 등과도 관련이 있을 수 있어[15,18] 내시경 검사 시 나이, 약제 복용력, 과거 H. pylori 감염력 등 여러 상황을 고려하여 판단해야 한다(Fig. 1).

H. pylori 현감염 내시경 소견

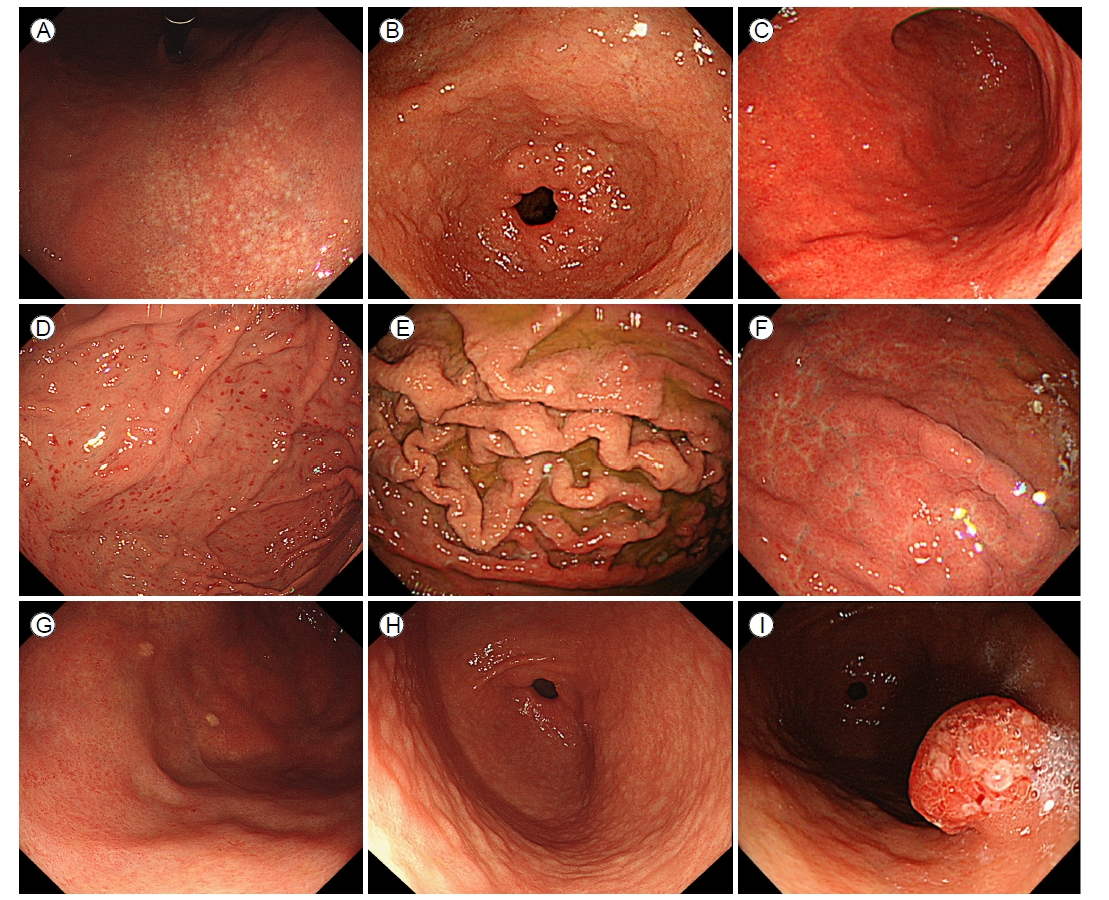

H. pylori 감염과 연관된 내시경 소견은 주로 전정부보다 체부(corpus)에서 뚜렷하게 나타난다(Fig. 2) [19]. 현감염 소견의 가장 대표적인 것으로 미만성 발적과 균일한 혈관상의 소실이 있다. H. pylori로 인한 염증을 동반한 위점막에서는 점막 표층에 존재하는 모세혈관의 울혈 및 확장에 의하여 점막 전체가 붉은 발적을 뛰게 되는데, 이를 미만성 발적이라고 하며, 1 mm 미만의 다발성 점상 출혈부터 위체부에 광범위하게 나타나는 발적까지 보일 수 있다[12]. 이전 연구에서 Kato 등[10]은 미만성 발적이 H. pylori 감염을 보는데 진단적으로 유용한 소견이라 보고하였고, 이 외에도 미만성 발적 소견은 점막의 발적의 정도를 객관적으로 보여주는 척도인 헤모글로빈 인덱스(hemoglobin index)와도 연관성이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[20].

Endoscopic images of an individual with Helicobacter pylori infection. (A) Atrophy. (B) Intestinal metaplasia. (C) Diffuse redness. (D) Spotty redness. (E) Enlarged folds. (F) Mucosal edema. (G) Xanthoma. (H) Mucosal nodularity. (I) Foveolar hyperplastic polyp.

미만성 발적이 진행되면서 더 깊은 곳에 위치한 집합 세정맥이 점막 표면에서 관찰되지 않게 되는 소견이 균일한 혈관상의 소실인데, H. pylori 감염이 장기간 지속되는 경우 고유 위선의 감소로 인한 위축성 변화가 나타나기 시작하며, 이는 내시경 소견에서 점막 주름의 위축 및 점막하층에 존재하는 혈관상이 salt-and-pepper 모양으로 투영되어 관찰될 수 있다. 내시경 검사 시 위축의 정도와 범위는 Kimura-Takemoto 분류를 이용하여 유문부부터 체부까지의 확장 범위에 따라 C-1, C-2, C-3, O-1, O-2, O-3의 6단계로 구분할 수 있다. C는 close를, O는 open을 의미하며, 분문부부터 유문부까지 위축이 연결되지 않은 경우를 close type, 연결된 경우를 open type으로 분류한다[21]. 전정부에 국한된 점막의 위축 역시 H. pylori 감염 없이도 노화 현상으로 나타날 수 있다[22].

위축이 진행됨에 따라 장상피화생이 나타나며, 이는 내시경 검사에서 회백색조의 편평 융기가 다발성으로 관찰되는 소견으로 관찰된다. 장상피화생의 정확한 진단을 위해서 methylene blue 염색을 하여 장상피화생 부분이 청색으로 변하는 소견을 관찰하기도 하지만, 임상에서 많이 사용되지는 않는다. 최근에는 영상 강화 내시경을 이용하여 light blue crest (LBC)가 보이거나 NBI에서 점막 상피에 백색 물질이 부착되어 있는 white opaque substance (WOS) 소견, indigo carmine 색소 내시경에서 위소구의 크기와 모양이 불규칙한 소견 등이 있는 경우 장상피화생을 추정할 수 있다[23].

그 외 H. pylori 감염과 관련된 내시경 소견으로는 점막 부종(mucosal edema), 위체부 주름의 종대(enlarged fold)와 사행(tortuous fold), 위저선 영역의 점상 발적(spotty redness), 백탁 점액(sticky mucus), 황색종(xanthoma), 닭살 모양의 결절성 변화(nodularity), 선와상피-과형성성 용종(foveolar-hyperplastic polyp) 등이 있다. 결정성 변화는 림프소구성 증식의 결과로, 나이가 증가함에 따라 위축성 변화로 진행될 수 있으며, 여성에서 많은 빈도로 관찰되고, 높은 혈청 H. pylori 항체 수치와 연관이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[24-29]. 황색종은 약 1-5 mm 크기의 노란색 판으로, 지질을 포함하는 거품성 조직구(foam histiocytes)로 구성되며 풍부한 액포 세포질을 가지고 있다[30]. 이런 황색종은 H. pylori 감염 소견을 시사하나 제균 치료를 해도 호전되지 않으므로 H. pylori 감염의 영구적인 흔적으로 볼 수 있다[31].

H. pylori 기감염 내시경 소견

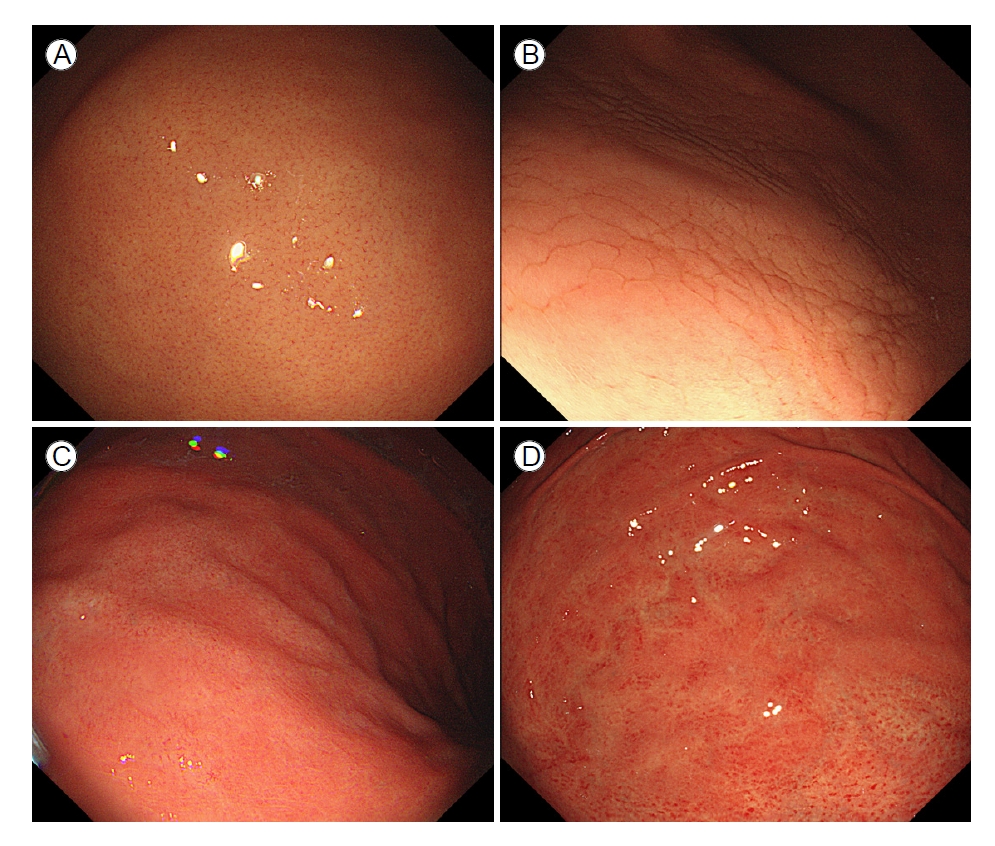

H. pylori 제균 치료 후 위점막의 내시경 소견이 호전되는데, 이는 만성적인 염증이 줄어들면서 보이는 변화이며, 조직학적으로는 다핵구 침윤과 단핵구 침윤이 호전된다. 이러한 염증 반응의 호전은 제균 치료 직후부터 몇 년간에 걸친 장기간의 변화를 보이므로, 제균 치료 후의 내시경적 관찰 시기에 따라서 H. pylori 현감염 소견과 기감염 소견들이 동반되어 발견될 수 있다. 기감염에서 대표적으로 보이는 소견들로는 지도상발적(map-like erythema)과 다발성 백색 편평 융기(multiple white and flat elevated mucosal lesions)가 있으며, 황색종의 경우 현감염 당시에 생기면 사라지지 않고 지속되므로 기감염 환자에게서도 관찰될 수 있다. 이 중 지도상 발적은 기감염에 매우 높은 특이도를 보이는 대표적인 소견으로, 조직학적으로는 장상피화생에 해당한다[32-34]. 지도상 발적이 나타나는 기전은 성공적인 제균 치료 이후 미만성 발적이 소실되고, 비위축성 점막과 위축성 점막의 대비(contrast)가 강화됨에 따라 생기는 것으로 설명할 수 있다[35]. 제균 치료 성공 후 점상 발적, 미만성 발적, 점막 종창, 위주름 종대 및 백탁 점액은 호전되는 경우가 많으며, 제균 치료 이후 배경 점막에 균일한 혈관상이 다시 보이는 소견과 위축의 경계가 불분명해지는 소견이 과거 감염을 나타낸다는 보고도 있다(Fig. 3) [22,36].

제균 치료 성공률과 연관이 있는 위점막 소견

이전 Kato 등[12]이 시행한 다기관 후향적 연구에서 126명의 환자의 제균 치료 전 후 내시경적 소견을 분석하였을 때, 위액의 혼탁, 미만성 발적, 주름의 종대, 점상 발적, 편평 미란과 헤모글로빈 인덱스가 제균 성공 그룹과 실패 그룹 간 유의하게 다른 소견을 보였다. 본 연구진이 시행한 연구에서 228명의 H. pylori 양성 환자를 대상으로 제균 치료 시행하기 전 위 내시경 소견 분석 시제균 치료 실패 환자들에서 성공한 환자들보다 미만성 발적과 백탁 점액의 비율이 유의하게 높은 결과를 보였다(66.7% vs. 43.9%, p= 0.033 and 46.7% vs. 26.8%, p= 0.044) (unpublished data).

근접 점막 패턴을 이용한 H. pylori 위염의 예측

내시경 선단부를 위 체부의 점막에 근접하여 점막의 패턴을 분석 및 분류하여 H. pylori 감염 상태를 예측하는 국내 전향적 연구에서 점막 패턴은 1) 정상 혈관상, 2) 모자이크 패턴의 점막(type A), 미만성 균질성 발적(type B), 비정형 패턴 (type C)으로 나누었다[37]. 정상 혈관상을 보이는 점막에서는 H. pylori가 9.4%만 나온 반면, type A 점막에서는 87.7%, type B 점막에서는 98.1%, type C 점막에서는 90.9% 비율로 H. pylori 양성이 나왔으며, H. pylori 예측 정확도 역시 91.6% 로 나타났다. 조직학적 소견에서 type B 점막에서 조직학적 위축의 정도가 심하였으며, type A 점막과 type B 점막에서 장상피화생이 유의미하게 높은 비율로 관찰되었다(Fig. 4).

Normal mucosal pattern and three types of abnormal mucosal patterns in the gastric corpus within a distance of ≤ 10 mm from the scope tip to the mucosa. (A) Normal, regular arrangement of collecting venules. (B) Mosaic-like appearance (type A). (C) Diffuse homogenous redness (type B). (D) Untypical pattern (type C).

NBI endoscopy를 활용한 H. pylori 위염의 예측

내시경 해상도의 발전과 더불어 기존의 white-light endoscopy (WLE)가 아닌 NBI 기술을 이용하여 점막 패턴을 분석하는 시도들이 있었다. 2011년 Alaboudy 등[38]은 NBI를 이용하여 위점막을 다음의 4가지 형태로 분류하였다: 1) type 1: regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) present, 2) type 2: cone-shaped gastric pits, 3) type 3: ground-glass appearance, 4) type 4: dark brown patches with bluish margins and irregular borders. 이후에 미국과 유럽에서 시행한 전향적 연구 결과, H. pylori gastritis를 WLE와 NBI를 이용하여 진단 시 NBI가 WLE보다 조금 높은 민감도와 특이도를 보였지만 통계적 유의성을 보이지 못하였고, WLE와 NBI의 정확도 역시 73%와 74%로 큰 차이를 보이지 못하였다[39].

2021년 확대 내시경 및 NBI를 이용한 국내 연구에서 체부 점막의 미세한 핏 패턴 관찰을 통해 H. pylori 감염을 예측하였고, NBI 및 확대 내시경은 H. pylori 위염 진단 시 96.3%의 민감도와 95.6%의 특이도 및 96.1%의 정확도를 보여 WLE를 이용한 H. pylori 진단보다 뛰어난 성적을 보여주었다. 이 연구에서는 핏의 모양을 이용한 4가지 분류 체계를 다음과 같이 분류하였다: 1) 정상 혈관상과 정상 핏을 보여주는 정상 패턴, 2) 다각형의 홈이 있는 규칙적인 핏을 보여주는 패턴(type Z-1), 3) 홈이 없고 확장되고 선형의 핏을 보여주는 패턴(type Z-2), 4) 코일형 미세 혈관과 소실된 핏을 보여주는 패턴(type Z-3) [40]. 정상 패턴의 점막에서는 6.5%에서 H. pylori가 양성이었던 반면에 type Z-1, Z-2, Z-3에서는 각각 97.6%, 96.3%, 100%의 확률로 H. pylori가 양성이 나와 우수한 예측력을 보여주었다[40].

Blue laser imaging과 linked-color imaging

최근 내시경 영상 기술의 또 다른 발전으로 FUJIFILM (Tokyo, Japan)에서 개발된 blue laser imaging (BLI)과 linked-color imaging (LCI)이 있다. LCI와 BLI는 각각 410 nm의 청자색과 450 nm의 청색의 단파장에서 위점막의 미세구조를 명확하게 묘사할 수 있는데, Dohi 등[41]이 2016년에 시행한 첫 번째 H. pylori 진단 연구에서 H. pylori 양성은 85.8%의 정확도를 보였다. 이후 Nishikawa 등[42]이 441명의 환자를 대상으로 한 BLI 연구에서, 위점막의 패턴을 “점상(spotty)”, “균열된(cracked)”, “얼룩진(mottled)”으로 분류하였고, 이 중 H. pylori 감염과 점상 점막 패턴과의 연관성 및 균열된 점막과 제균 후의 점막 변화, 얼룩진 점막과 장상피화생과의 연관들을 밝혀내었다.

인공지능을 통한 H. pylori 감염의 진단

최근 딥러닝 기술이 발전되고 특히 컨볼루션 신경망(convolutional neural network, CNN) 기술이 도입됨에 따라 영상 자료를 다루는 기계학습 분야에서 패러다임의 전환이 일어났다. CNN은 영상으로부터 패턴 인식을 하는 데 이용되는 알고리즘으로, feature 추출부터 분류까지의 전체 과정을 하나의 모델로 가능하게 하였다. 즉 원하는 영상과 분류해 내고자 하는 output 데이터만 있으면 쉽게 좋은 분류 성능을 갖는 프로그램을 얻을 수 있게 하는 것이다. CNN은 단순한 영상 분류 문제를 넘어 검출(detection)과 분할(segmentation) 문제 등으로 응용될 수 있어 의료 영상을 다루는 다양한 딥러닝 연구에서 필수적인 기술이 되었다. 최근에는 이런 CNN 기술을 이용하여 만든 소프트웨어를 통해 H. pylori 감염 상태를 진단하는 연구가 활발히 이루어지고 있다.

이 중 대부분의 연구는 백색광 내시경 이미지를 이용하여 이루어지는데, H. pylori 감염이 있는 위 내시경 사진과 정상 위 내시경 사진을 이용하여 모델을 training시킨 후 testing하는 형식으로 연구가 진행되었다. 최근 발표된 메타분석 연구에 따르면 H. pylori 감염을 예측하는 CNN 기술의 정확도는 87.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 81.8-91.1), 민감도 86.3% (95% CI, 80.4-90.6), 특이도 87.1% (95% CI, 80.5-91.7)를 보이고 있다. 이에 반해 내시경 의사들이 시행한 H. pylori 진단의 visual accuracy는 82.9% (95% CI, 76.7-87.7), 민감도 79.6% (95% CI, 68.1-87.7), 특이도 83.8% (95% CI, 72-91.3)로, CNN 기술을 이용한 인공지능 모델이 H. pylori 진단에 도움이 될 수 있는 가능성을 보여주었다[43].

하지만 아직까지 CNN 기술을 이용하여 H. pylori 감염 여부를 예측하는 연구들은 실제 임상이 아닌 연구실에서 이루어졌으며, 전향적 연구는 보고된 바가 없고, 대부분의 연구가 백색광 내시경 이미지를 이용하여 진행되었다는 한계가 있다. 그러나 최근 H. pylori 감염 여부를 진단하기 위한 다양한 연구들이 활발하게 진행되고 있어, 가까운 미래에는 실제 임상에서 인공지능 모델이 사용될 것으로 기대되고 있다.

결 론

내시경 해상도 및 화질의 개선으로 인해 위점막의 자세한 관찰이 가능해짐에 따라, 내시경 소견으로 H. pylori의 감염 상태를 어느 정도 파악하는 것이 가능해졌다. 위암 발병률이 높은 한국이나 일본에서 이러한 H. pylori 감염 여부에 따른 위 내시경 소견 연구가 활발히 이루어지고 있으며, 특히 전 국민의 50% 정도가 H. pylori에 감염되어 있는 우리나라에서 내시경 소견을 통해서 H. pylori의 감염 여부를 파악하는 것이 다른 진단 방법과 함께 동반된다면, H. pylori 감염의 진단 정확도를 높일 수 있을 것이다. 이에 현재 알려진 H. pylori 감염 의심 소견 외에도, 여러 가지 내시경 소견 및 관련 요인들에 대한 더욱 자세하고 세밀한 연구가 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Drafting the article: Jun-young Seo

Critical revision for intellectual content: Ji Yong Ahn

Acknowledgements

None.