2021 대한부정맥학회 심방세동 환자의 뇌졸중 예방 관리 지침

2021 Korean Heart Rhythm Society Guidelines for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation

Article information

Trans Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a strong risk factor for ischemic stroke and systemic embolism. To prevent thromboembolic events in patients with AF, anticoagulation therapy is essential. The anticoagulant strategy is determined after stroke and bleeding risk assessments using the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, respectively; both consider clinical risk factors. Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are the sole anticoagulant option in AF patients with a prosthetic mechanical valve or moderate-severe mitral stenosis; in all other AF patients VKA or non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants are therapeutic options. However, antiplatelet therapy should not be used for stroke prevention in AF patients. Anticoagulation is not needed in AF patients with low stroke risk but strongly recommended in those with a with low bleeding risk. Left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion offers an alternative in AF patients in whom long-term anticoagulation is contraindicated. Surgical occlusion or the exclusion of LAA can be considered for stroke prevention in AF patients undergoing cardiac surgery. In this article, we review existing data for stroke prevention and suggest optimal strategies to prevent stroke in AF patients.

서 론

심방세동은 허혈성 뇌졸중과 전신색전증의 강력한 위험 인자로서, 이를 예방하기 위한 항응고 치료는 필수적이다. 항응고 치료는 환자의 기저 질환과 뇌졸중 및 출혈 위험도에 따라 결정된다. 뇌졸중과 출혈 위험도는 각각 관련 임상 위험인자를 종합한 점수제에 따라 결정되고, 항응고제로서 비타민 K길항제(vitamin K antagonist, VKA)와 비 비타민 K 길항제 항응고제(non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, NOACs)를 적응증에 따라 사용할 수 있다.

심방세동 환자에서 항응고 치료 전략은 1) 환자 기저 질환(기계판막 치환술을 시행받거나 중등도 이상의 승모판 협착), 2) 저위험군 환자 선별, 3) 고위험군 환자에서 항응고제의 선택, 4) 출혈 위험도의 최소화에 따라 시행된다. 대한부정맥학회에서는 현재까지 발표된 문헌 고찰을 통해 뇌졸중 위험도와 출혈 위험도에 사용되는 임상인자에 대한 적절성을 평가하고, 이를 종합한 위험도 점수제에 따른 적절한 항응고 치료 전략을 제시하고자 한다.

본 론

뇌졸중 위험의 평가

대체적으로 심방세동은 뇌졸중 위험을 5배 증가시키는데, 이는 항상 그런 것은 아니며 특정한 위험인자나 조정인자들에 의해 결정된다. 주요한 뇌졸중 위험인자는 20여 년 전부터 역사적인 임상 연구를 통해 확인되고 있으나 이러한 연구들이 선별 환자의 10% 이하만 포함하고 여러 주요한 위험인자들이 기록되지 않았거나 정의가 일정치 않은 문제가 있었다[1]. 이런 문제점은 기존 무작위 임상 연구에 포함되지 않은 환자들을 대상으로 한 대규모 코호트를 이용한 관찰 연구의 데이터로 보완되고 있는 상황이다. 결과적으로 여러 영상 자료나 혈액, 소변의 생체 표지자들이 뇌졸중 위험인자와 연관됨이 밝혀지고 있다(Table 1) [1,2]. 더불어 비발작성 심방세동이 발작성 심방세동에 비해 혈전/색전증의 위험도가 높았다(보정 위험도 1.38; 95% confidence interval 1.19-1.61; p<0.001) [3]. 특히 많은 심방세동 관련 합병증의 위험인자가 우연히 발견된 심방세동에서도 동일하게 적용됨을 알 수 있었다[4].

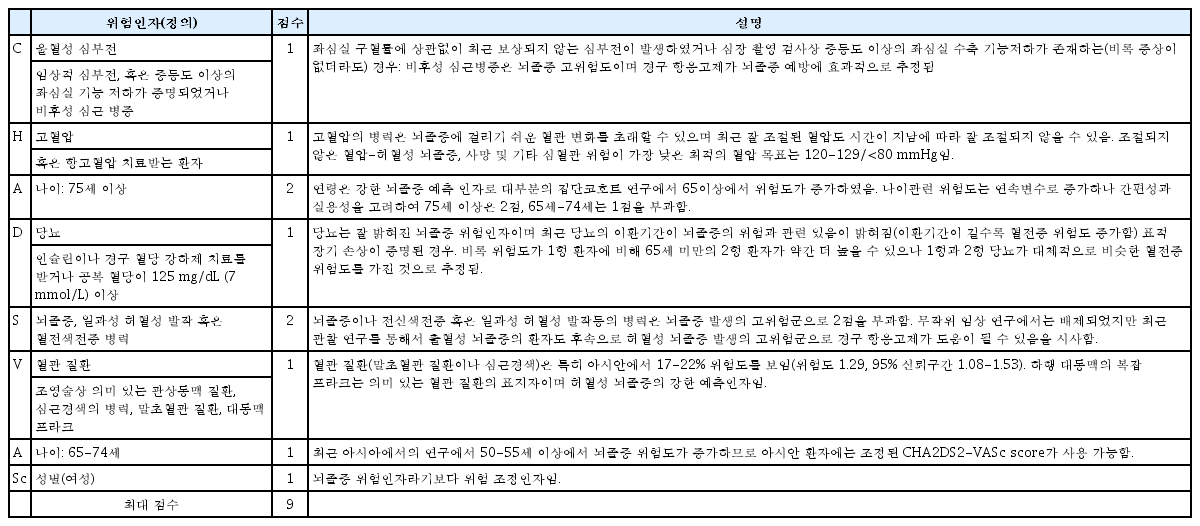

뇌졸중 위험인자는 임상 위험인자 기반 CHA2DS2-VASc (울혈성 심부전, 고혈압, 연령 75세 이상, 당뇨병, 뇌졸중, 혈관 질환, 연령 65-74세, 성별 카테고리 [여성]) 점수가 가장 많이 사용된다(Table 2) [5,6]. CHA2DS2-VASc는 혈전 색전증 발생 고위험 환자 예측은 조금 약하나, 뇌졸중 위험이 낮은 환자(CHA2DS2-VASc 0 [남성] 또는 점수 1 [여성])를 찾아내는 데 우수하다[7,8].

비후성 심근 병증의 경우 뇌졸증 위험도가 다른 질환에 비해 상대적으로 높아 2점 정도로 계산하는 것이 적정하나 현재의 CHA2DS2-VASc 체계가 복잡해져 현실적인 사용이 어려운 점이 있어 유럽 학회의 진료 지침과 마찬가지로 심부전의 일환으로 간주하여 점수를 배정하는 것으로 하였다[9]. 여성은 연령에 따른 뇌졸중 위험인자 그 자체라기보다는 위험수정인자이다[10,11]. 관찰 연구들에 따르면 여성은 다른 위험인자가 없는 경우(CHA2DS2-VASc 점수 1점) CHA2DS2-VASc 점수가 0인 남성과 유사한 낮은 뇌졸중 위험도를 가진 것으로 확인되었다[12]. 성을 고려하지 않은 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수는 초기 항응고 치료를 결정하는데 도움이 되나, 여성 심방세동 환자의 뇌졸중 위험도를 과소 평가할 수 있다[13,14]. 성별 외 뇌졸중 위험인자 1개 이상 있는 여성은 지속적으로 남성보다 훨씬 더 높은 뇌졸중 위험을 가지고 있다[15-18].

신장 장애, 수면무호흡증, 좌심방 확장 등 많은 임상 뇌졸중 위험요소는 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수와 밀접한 관련이 있지만 단독으로 뇌졸중 위험의 예측 정도를 향상시키지 않는다[12,19-23]. 흡연 또는 비만과 뇌졸중 위험의 관계도 아직 논쟁의 여지가 있다[24-27]. 트로포닌, 나트륨 이뇨 펩티드, 성장 분화 인자(growth differentiation factor, GDF)-15, von Willebrand factor 등 다양한 생체 표지자는 뇌졸중과 출혈 모두를 예측하는 인자이고[28,29], 또한 비특이적으로 다른 심질환을 반영함에도 불구하고 임상 점수에 기반한 것보다 우수한 성능을 보여주었다[28,30].

출혈 위험도 평가

항응고 치료를 시작할 때는 반드시 출혈 위험인자에 대한 평가도 동시에 수행해야 한다. 교정 가능한 인자와 함께 교정 불가능 인자 또는 부분적 교정 가능 인자가 만나게 되면 출혈 위험도는 급격히 상승한다(Table 3) [31]. 특히 낙상의 기왕력은 출혈의 위험인자가 아님을 주지해야 한다. 낙상으로 인한 출혈 위험도가 항응고제 치료로 인한 허혈성 뇌졸중 감소 효과를 상쇄하려면 연간 295번 이상 낙상해야 한다는 결과가 이를 반영해준다[32].

HAS-BLED 점수제는 출혈 저위험군(HAS-BLED 점수 0-2)을 선별하는 데 우수한 결과를 보여주었다[33]. 38개의 출혈 위험도 평가 점수제의 출혈 위험 예측 정확도를 평가한 PCORI review [34]에서 HAS-BLED 점수제가 가장 강력한 예측도를 보였고, 다른 meta-analysis 역시 HAS-BLED 점수제 예측력이 가장 좋았다[35-37]. 생체 표지자를 기본으로 제작한 ABC 출혈 위험도 평가 점수제는 나이(age), 생체 표지자(biomarker; GDF-15, cTnT-hs, hemoglobin 등), 임상 상황(clinical history; 과거 출혈)으로 구성되어 있다[38,39]. 이 점수제는 몇몇 연구에서 우수한 출혈 예측력을 보인 반면, 다른 연구들에서 HAS-BLED 점수제에 비하여 장기간 예측력은 낮았다(Table 4).

출혈 위험도 점수가 높다고 해서 항응고 치료를 중단하는 일은 없어야 한다. 항응고 치료로 얻을 수 있는 임상적 이익이 훨씬 크기 때문이다. 오히려 출혈 위험도 점수를 평가하여 점수가 높은 환자는 더 일찍, 그리고 더 자주 내원하게하여 교정 가능 위험인자를 재평가하고 관리해야 한다[31,40]. 출혈 고위험군 환자 파악은 경피적 관상동맥 중재술과 같은 특별한 심방세동 환자 그룹에서 항응고 치료를 결정하는 데도 필요하다.

항응고제 사용의 절대적 금기증

항응고제를 사용해서는 안되는 절대적 금기증은 현재 진행 중인 중증 출혈(출혈 부위는 반드시 확인하고 치료되어야 함), 중증 혈소판 감소증(혈소판 < 50/uL), 검사를 요하는 중증 빈혈, 뇌출혈과 같은 최근에 발생한 고위험 출혈 사건 등이다. 이러한 경우 약제가 아닌 다른 치료 방법을 고려해볼 수 있다.

뇌졸중 예방 치료

비타민 K 길항제

비타민 K 길항제(대부분 warfarin을 의미함)는 대조군 또는 위약군에 비하여 뇌졸중을 64%, 사망률을 26% 감소시킨다[41]. 비타민 K 길항제는 여전히 전 세계에서 많은 환자들에게 사용 중이고, 류마티스성 승모판막 질환, 인공판막 환자에서 사용할 수 있는 유일한 항응고 치료법이다.

비타민 K 길항제는 international normalized ratio (INR) 모니터링을 통하여 지속적으로 용량을 변경해야 하며, INR 수치의 좁은 치료 구간으로 인하여 사용이 제한적이다[42]. 치료 농도 유지 시간(time in therapeutic range [TTR] > 70%)를 유지하는 비타민 K 길항제 치료는 효과적이고 비교적 안전하다[43,44]. 비타민 K 길항제 적정 혈중 농도 조절(Rosendaal 방법에 의한 TTR 계산, 치료 범위 내 INR 빈도 수)은 혈전색전증 사건, 주요 출혈 사건과 반비례한다[45]. TTR 수치가 높은 경우, 비타민 K 길항제의 뇌졸중 예방효과는 NOAC과 비슷하다[46]. 반면 NOAC은 TTR에 영향을 적게 받으므로, 뇌출혈과 같은 주요 출혈 위험도는 비타민 K 길항제에 비하여 낮다. 하지만, 두 약제 사이의 출혈 위험도 발생의 절대적 차이는 작다[47,48].

유전적 요인, 동시 사용 약제 등 많은 인자들이 비타민 K 길항제의 항응고효과에 영향을 미친다. 이러한 인자 중 가장 많이 사용하는 인자를 모아서 SAMe-TT2R2 점수제를 제안하였고, 이 점수가 2점을 초과하는 경우 적절한 TTR 획득이 어렵다고 알려져 있다. 이런 경우 NOAC을 사용하거나, TTR 점수를 향상시키기 위해 INR 검사를 더 자주하거나, 환자를 더 자주 면담하는 등의 노력을 기울여야 한다[49]. SAMe-TT2R2 점수제에 포함된 인자는 Sex (female), Age (< 60세), 두 가지 이상의 동반 질환력(medical history; 고혈압, 당뇨병, 관상동맥 질환, 말초혈관 질환, 뇌졸중의 과거력, 폐질환, 간질환, 신질환), 치료약제(treatment; amiodarone과 같은 상호 작용 약제), 담배(tobacco), 인종(race, 백인이 아닌 인종)으로 구성되어 있다[50].

비 비타민 K 길항제 항응고제

아픽사반(apixaban), 다비가트란(dabigatran), 에독사반(edoxaban), 리바록사반(rivaroxaban) 각각 NOAC에 대한 무작위 전향적 연구에서 이들 약제는 와파린에 비하여 뇌졸중과 전신색전증 예방에 있어 비열등함이 증명되었다[51-54]. 이들 무작위 연구를 종합한 메타분석에서 NOAC은 와파린에 비하여 뇌졸중과 전신색전증 위험도는 19%, 출혈성 뇌졸중 위험도는 51% 감소시켰지만[55], 허혈성 뇌졸중 위험도는 비슷하였다. 하지만, 모든 원인에 의한 사망률은 NOAC 사용으로 10% 감소하였다. 주요 출혈 위험도는 14% 감소하였으나 통계적으로 차이를 보이지 않았고, 뇌출혈 위험도는 유의하게 52% 감소하였으나 위장관 출혈은 오히려 25% 위험도가 증가하였다[55].

NOAC 사용과 관련한 주요 출혈 위험도 감소는 와파린 사용에 따른 INR 관리가 좋지 못할 때(TTR < 66%) 유의하게 증가하였다. NOAC 연구를 메타분석한 연구는 표준 용량 NOAC 사용은 와파린과 비교하여 동양인에서 비동양인에 비하여 훨씬 효과적이고 안전함을 보여주었다[56,57]. 비타민 K 길항제를 사용할 수 없거나 거부하였던 심방세동 환자를 대상으로 하였던 AVERROES 연구는 아픽사반 5 mg 하루 2회 사용이 아스피린과 비교하여 유의한 뇌졸중과 전신색전증 위험도 감소와 유사한 주요 출혈 및 뇌출혈 위험도를 보여주었다[58].

아픽사반, 다비가트란, 에독사반, 리바록사반의 시판 후 관찰 연구에서 와파린과 비교한 유효성과 안전성 평가는 무작위 전향적 연구와 동일한 결과를 보였다[59-65]. 이러한 정보는 심방세동 환자에게 반드시 제공되어서 항응고 선택에 이용될 수 있게 해야 한다.

치료 지속성은 와파린 대비 NOAC 치료가 우월하다고 알려져 있다. 이는 NOAC의 우수한 약동학적 특성과 우수한 유효성과 안전성(노인, 신질환, 뇌졸중 기왕력이 있는 취약군 포함)에 기인한다[66-68]. 말기 신질환이 주요 무작위 전향적 연구에서 제외되었으나, 리바록사반, 에독사반, 아픽사반의 경우 Cockcroft-Gault equation을 이용한 사구체 여과율(creatinine clearance, CrCl) 15-30 mL/min을 보이는 중증 신질환 환자군에서 용량을 감량하여 사용해볼 수 있다[69,70]. 실제 진료 현장에서는 NOAC 용량이 부적절하게 감량되어 처방되고 있다[65,71]. 이는 뇌졸중/전신색전증 위험도 증가, 입원률 증가, 사망률 증가와 관련되고, 출혈 위험도 감소 효과는 기대할 수 없다[72-75]. 따라서, NOAC 치료는 각기 다른 환자군에서 유효성 및 안전성 인자에 따라 최적화되어야 한다(Table 5) [76].

항혈소판요법

ACTIVE W 연구에서 aspirin과 clopidogrel을 이용한 이중 항혈소판요법과 와파린을 비교하였고, 이중 항혈소판요법은 와파린보다 뇌졸중과 전신색전증, 심근경색증, 혈관성 사망(연간 발생 위험도 5.6% vs. 3.9%, p=0.003) 예방에 있어 열등하였고, 주요 출혈 위험도는 비슷하였다[77]. ACTIVE-A 연구는 항응고 치료에 적합하지 않은 환자를 대상으로 하여 aspirin 단독 요법과 aspirin과 clopidogrel을 이용한 이중 항혈소판요법을 비교하였고, 이중항혈소판요법은 아스피린 단독요법에 비하여 혈전색전증 위험도는 감소시켰지만, 주요 출혈은 유의하게 증가시켰다[78]. 아스피린 단독요법은 항응고 치료를 받지 않는 대조군과 비교하여 뇌졸중 예방에 있어서는 효과적이지 못하였고, 노인 환자에서 허혈성 뇌졸중 위험도를 증가시켰다[79].

결론적으로, 항혈소판 단독 요법은 뇌졸중 예방에 효과적이지 못하고, 오히려 해로운 효과만 증가시킨다. 이 효과는 특히 노인 환자에서 두드러진다[80,81]. 이중항혈소판 요법은 항응고 치료와 비슷한 출혈 위험도를 보인다. 따라서, 항혈소판요법은 심방세동 환자에서 뇌졸중 예방을 위해 사용해서는 안된다.

항혈소판제와 항응고제 복합 사용

항혈소판제는 심방세동이 아닌 말초혈관 질환, 관상동맥 질환, 뇌혈관 질환 등에 광범위하게 사용되고 있다. 하지만, 항혈소판제와 항응고제 복합 요법이 심방세동 환자에서 뇌졸중 예방 효과에 대한 근거는 부족하고, 뇌졸중, 심근경색증, 사망률 감소 효과 역시 근거가 부족하다. 이러한 이득 없이 오히려 주요 출혈과 뇌출혈만 증가시킨다고 보고된다[80,81].

좌심방이 폐색술과 배제술

좌심방이 폐색 기구들

오직 Watchman 기구만이 무작위 대조군 연구인 PROTECT AF (WATCHMAN Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) 연구와 PREVAIL (Watchman LAA Closure Device in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Versus Long Term Warfarin Therapy) 연구에서 비타민 K 길항제와 비교되었는데, 뇌졸중 위험도가 중등도 이상인 환자군에서 좌심방이 폐색술은 비타민 K 길항제와 비교하였을 때 열등하지 않음을 보여주었고, 장기간의 추적에서도, 출혈 위험을 감소시킬 수 있는 것으로 나타났다[82-85]. 항응고 치료의 금기증에 해당하는 환자들에서 좌심방이 폐색술은 뇌졸중 위험도도 낮추어 줄 수 있는 것으로 나타났다[83,86].

유럽에서 진행된 대규모 등록 연구에서 높은 시술 성공률(98%)을 보고하였으며, 1개월 이내의 시술 관련 합병증 발생은 4%였다[87]. 그러나 시술 과정에서 심각한 합병증이 발생할 수 있고(실제 임상 현장에서는 기업이 후원한 연구에서보다 더욱 많은 합병증의 발생을 보고하였고, 보고 편향의 가능성이 있다), 폐색 기구 관련된 혈전은 심각한 결과로 이어질 가능성이 있다[88-91]. 좌심방이 폐색술 후 항혈전 치료에 대해서는 무작위 대조군 연구에서는 다루어지지 않았으며, 역사적인 연구들을 근거로 하고 있으며 최소한 아스피린을 포함하고 있다(Table 6). 어떤 항혈소판제도 견디지 못하는 환자라면 심외막 접근법이나 흉강경을 이용한 좌심방이 클립술 선택을 고려해볼 수 있다[92,93].

주목할 만한 점은, 비타민 K 길항제와 비교하였을 때 좌심방이 폐색술의 비열등성은 대부분 출혈성 뇌졸중 발생 감소에 의한 것이며, 허혈성 뇌졸중은 증가하는 경향을 보이고 있었다는 점이다. 따라서 좌심방이 폐색술은 심방세동 관련 뇌졸중을 감소시키는 효과가 제한적일 수 있다는 것을 간과해서는 안된다는 것이다. 좌심방이 폐색술 후 경구 항응고제를 중단하는 것은 심방 심근병증과 연관된 총 뇌졸중 위험을 불충분하게 치료하는 결과가 될 수 있다.

수술적 좌심방이 폐색술 혹은 배제술

수술적 좌심방이 폐색술 혹은 배제술의 타당성과 안전성을 보여주는 여러 관찰 연구들이 있지만 잘 통제된 연구는 그 수가 매우 적다[94-96]. 좌심방이의 불완전한 폐색은 뇌졸중의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다[97]. 대부분의 기존 연구에서는 좌심방이 폐색술 혹은 배제술은 다른 개심술과 함께 시행되었으나, 최근에는 외과적인 심방세동 절제술과 함께 시행되었거나 흉강경 단독시술로 시행되었다[96,98]. 심장 수술과 함께 좌심방이 폐색술을 진행하는 대규모 무작위 대조군 연구가 진행 중이다[99].

좌심방이 폐색술/배제술의 가장 흔한 임상적 치료 근거는 높은 출혈 위험성이고, 그 다음으로 흔한 사유는 경구 항응고제의 금기증이다[87]. 그러나, 그와 같은 환자들을 대상으로 좌심방이 폐색술은 무작위 연구로 시험한 것은 없었다. 수년 전에는 경구 비타민 K 길항제를 이용한 항응고 치료에 부적절할 것으로 여겨졌던 환자들이 현재는 NOAC 치료로 잘 지내고 있는 것처럼 보인다[100-102]. 좌심방이 폐색술은 출혈 위험이 있는 환자에서 NOAC과 비교된 적이 없고, 수술적 좌심방이 폐색술 혹은 배제술과도 비교된 적이 없다. 이와 같은 환자들에서 장기적인 치료법으로는 아스피린이 흔한 치료법인데[103], 아스피린을 잘 유지할 수 있다면 NOAC이 더 좋은 치료법일지도 확인이 필요하다. 항응고 치료 중에 발생한 허혈성 뇌졸중 환자들과 항응고 치료의 상대/절대 금기증에 해당하는 환자들에서 좌심방이 폐색술/배제술과 NOAC 치료를 비교한 적절한 통계적인 검정력을 가진 연구가 필요하다. 그리고 좌심방이 폐색술 후의 적절한 항혈전 치료에 대한 연구도 필요하다.

심방세동 부담에 따른 장기적인 경구 항응고 치료

발작성 심방세동과 비교하였을 때, (오래된) 지속성 심방세동에서 허혈성 뇌졸중, 전신성 색전증의 위험이 높고, 심방세동의 진행은 많은 부작용과 관련이 있다[104,105]. 임상적으로 심방세동의 시간적인 양상(발작성, 지속성, 오래된 지속성)에 따라서 항응고 치료를 결정해서는 안되고, 뇌졸중 위험인자에 따라서 결정하여야 한다[3]. 심방빈맥사건 환자는 임상적으로 확진된 심방세동 환자보다 뇌졸중 위험도가 낮고[106], 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동과 뇌졸중 발생 사이에는 시간적인 연관성이 불분명하기 때문에[107,108], 심방빈맥사건은 뇌졸중의 위험인자라기보다는 위험 표지자로 보는 것이 적절하다[109,110]. 심방빈맥사건과 무증상 심방세동이 임상적인 심방세동과 같은 치료를 필요로 하는지는 아직까지 불분명하지만[111], 24시간 이상 지속되는 심방빈맥사건과 무증상 심방세동에서 항응고 치료의 임상적인 이득에 대해서 여러 무작위 대조군 연구가 진행 중이다[110].

특히, 무증상 심방세동/심방빈맥사건을 갖고 있는 환자들은 24시간 이상 지속되는 심방빈맥이나 임상적인 심방세동이 발생할 수 있다는 것이다. 따라서 주의 깊은 모니터링이 권장되며, 지속 시간이 긴 심방빈맥사건과 고위험군에서는 원격모니터링 사용도 고려해볼 수 있다[112]. 심방세동의 역동적인 특성과 뇌졸중 위험을 고려하였을 때, 한 번 기록된 심방빈맥사건의 지속 시간이 다음에는 똑같지 않을 수 있다.

증상 조절 치료 전략에서의 장기적인 항응고요법

증상 조절은 환자의 상태에 맞게 증상에 따라서 심박수 또는 리듬을 조절한다. 증상 조절 전략이 무엇이냐에 따라서 장기적인 항응고요법을 결정해서는 안된다. 항응고 치료는 동율동 유지 성공 여부와 무관하게 뇌졸중 위험인자에 따라서 결정되어야 한다.

항응고 치료에 따른 출혈 위험 관리

출혈 위험을 최소화하기 위한 전략

비타민 K 길항제 치료 농도 유지 시간(TTR > 70%)을 잘 유지하고 NOAC의 적정 용량(약제별 각각의 표준 용법에 따른 감량 기준)을 선택하는 것이 출혈 위험을 최소화하는 데 중요하다. 앞서 언급하였듯이, 환자가 매번 외래를 방문할 때마다 변화시킬 수 있는 출혈 위험인자를 주기적으로 확인하는 것을 포함하여, HAS-BLED 점수와 같이 정형화된 형식에 따라 출혈 위험도를 체계적으로 평가하는 것이 출혈 위험도가 높은 환자를 발굴하고 더욱 자주 추적하고 확인해야 하는지 결정하는 데 유용하다(예를 들어, 4-6개월 간격보다는 4주 간격) [40]. 항응고 치료를 받고 있는 환자에서 정기적으로 항혈소판제나 비스테로이드 소염제를 투여하는 것은 피해야만 한다. 출혈 위험은 역동적이며, 출혈 위험도가 변화하는 것을 주의 깊게 관찰함으로써 특히, 첫 3개월 간의 주요 출혈 사건 발생을 예측할 수 있다[31].

고위험군

특정 고위험 심방세동 환자군(90세 이상의 초고령 환자들, 인지 기능장애/치매, 최근이나 이전의 뇌출혈, 말기 신부전, 간기능 장애, 악성 종양 등이 동반된 환자들)은 무작위 대조군 연구에서 적게 포함되어 있다. 관찰 연구들에서는 이와 같은 환자들이 허혈성 뇌졸중과 사망의 고위험군에 속해 있으며 대부분이 항응고 치료로 이득을 본 것으로 나타났다.

간기능 장애가 동반된 환자들은 비타민 K 길항제 사용 시 출혈 위험이 높지만 NOAC 사용 시에는 출혈 위험이 낮아질 것으로 보인다. 간경변을 동반한 환자들에서의 관찰 연구 결과, 허혈성 뇌졸중의 감소의 이득이 출혈의 위험을 상회하는 것으로 나타났다[113-115].

최근의 출혈 사건이 있었던 환자들에서 출혈을 일으켰던 원인 병태가 무엇이었는지(예를 들어, 위장관 출혈의 원인이 궤양 출혈이었는지, 용종에 의한 출혈이었는지) 밝히고, 경구 항응고제를 최대한 일찍 재투여하도록 결정하는 것이 다학제적 팀 치료의 일례이다. 약제를 결정할 때 와파린과 비교해서 apixaban이나 dabigatran 중 어떤 것이 위장관 출혈 위험이 적은지 등과 같은 점들을 고려해야 한다. 경구 항응고제 투여를 재개하지 않는 것이 투여를 재개하는 것에 비해서 뇌졸중과 사망의 위험이 높다[116]. 이와 유사하게, 암환자에서 혈전 예방 치료에 대해서 심각한 출혈과 뇌졸중 감소 효과의 균형 잡힌 결정을 위해서 다학제 진료팀이 필요한데, 출혈 위험도는 암의 종류, 위치, 병기, 항암 치료 등에 따라서 결정되기 때문이다.

뇌졸중을 피하기 위한 결정

관찰 연구 코호트에서 뇌졸중과 사망은 모두 임상적으로 의미 있는 사건이다. 왜냐하면 사망 사건 중 일부는 치명적인 뇌졸중 때문에 생길 수 있기 때문이다(인구 코호트에서는 사건들을 정확하게 분석하고 판단하지 않고 사건 발생에 관한 자료를 수집할 뿐이고, 뇌영상이나 부검이 강제적이지 않기 때문이다). 경구 항응고 치료를 통해서 뇌졸중과 사망이 대조군이나 위약군에 비해서 각각 64%와 26%만큼 유의하게 감소하였기 때문에[41], 뇌졸중과 사망은 혈전 예방 치료의 적절성을 평가하기 위한 적절한 기준이다.

뇌졸중 예방과 뇌출혈의 위험 사이의 균형을 유지하면서 뇌졸중 예방을 위한 항응고 치료를 시작하는 임계점은 와파린은 1.7%/년이며, NOAC은 0.9%/년이다(dabigatran 자료를 사용한 모델 분석 결과) [117]. 평균 치료농도 유지 시간이 70%를 넘게 잘 관리된 항응고 치료 시에는 와파린의 임계점은 더욱 낮아질 수 있다[118].

임상적 위험도 평가 점수의 한계, 뇌졸중 위험도의 역동적인 특성, 성별 이외의 위험인자를 1개 이상 보유한 환자에서 뇌졸중과 사망의 위험이 높은 것, 이와 같은 환자들에서 항응고 치료의 임상적인 순이득이 있다는 것을 고려하였을 때, 전문가들은 인공적으로 정의된 고위험군에 과도하게 집중하는 접근 방법보다는 임상적인 위험인자를 기반으로 한 뇌졸중 예방을 추천한다.

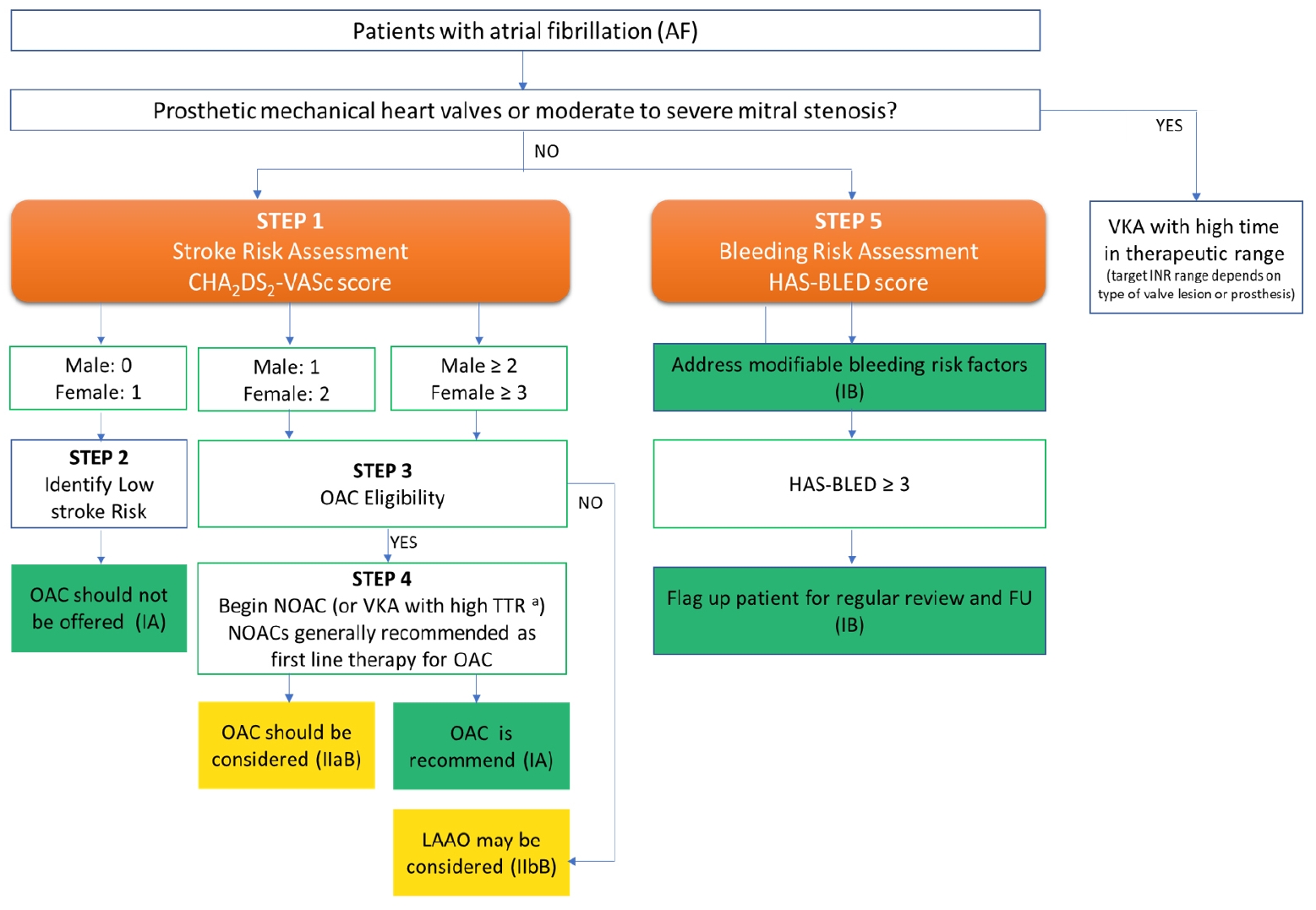

심방세동 환자에서 뇌졸중 예방을 위한 첫 번째 단계는 뇌졸중 발생 위험도를 CHA2DS2-VASc 점수를 환원주의적인 방식(위험도가 명백히 낮아서 항응고 치료가 필요치 않은 환자들을 제외한 모든 환자들을 뇌졸중 예방 치료의 대상으로 분류하는 방식)으로 적용해야 한다[119]. 두 번째 단계는 항혈전 치료가 필요 없는 저위험군 감별, 세 번째 단계는 성별을 제외한 1개 이상의 위험인자를 갖고 있는 환자들에게 장시간 항응고제 사용 가능성을 판단하는 것이다. 네 번째 단계는 경구 항응고제 사용이 가능한 환자인 경우, 경구 항응고제로서 NOAC (상대적인 효율성, 안전성, 편의성 등을 고려하여 심방세동 환자의 뇌졸중 예방을 위해서 일반적으로 1차 선택약제로 추천된다) 혹은 비타민 K 길항제(TTR > 70%) 사용을 시작하고, 경구 항응고제 사용이 불가능한 환자의 경우 좌심방이 폐색술을 고려할 수 있다. 다섯 번째 단계는 출혈위험도를 HAS-BLED 점수로 평가하고, 교정 가능한 출혈 위험인자를 파악하는 것이다. 교정 가능한 출혈 인자는 반드시 발굴하여 교정해주고, HAS-BLED 점수가 3점 이상인 환자의 경우 출혈 고위험군 환자로 분류(flag-up)하고 더 자주 추적 관찰해야 한다. 이와 같이 뇌졸중 위험도 층화와 치료 결정을 위한 ‘심방세동 5단계 환자 치료 과정’을 그림 1에 도식화하였고, 권고사항은 표 7에 정리하였다.

Anticoagulation/Avoiding Stroke Strategy in patients with atrial fibrillation. INR, international normalized ratio; LAAO, left atrial appendage occlusion; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; OAC, oral anticoagulant; SAMe-TT2R2, sex (female), age (<60 years), medical history, treatment (interacting drug[s]), tobacco use, race (non-caucasian) (score); TTR, time in therapeutic range; VKA, vitamin K antagonist. aIf a VKA being considered, calculate SAMe-TT2R2 score: if score 0-2, may consider VKA treatment (e.g. warfarin) or NOAC; if score 7gt; 2, should arrange regular review/frequent INR checks/counselling for VKA users to help good anticoagulation control, or reconsider the use of NOAC instead; TTR ideally > 70%.

결 론

심방세동 환자에서 뇌졸중을 예방하기 위한 항응고 치료는 환자 기저 질환, 뇌졸중 위험도 평가, 출혈 위험도 평가, 적절한 항응고제의 선택에 따라 결정된다. 기계판막 치환술을 시행받거나 중등도 이상의 승모판 협착을 동반한 심방세동 환자는 비타민 K 길항제만 항응고 치료제로 사용할 수 있다. 그 외 심방세동 환자는 뇌졸중 위험도에 따라 비타민 K 길항제 또는 NOAC을 사용할 수 있으며, NOAC 사용을 비타민 K 길항제보다 먼저 고려해보아야 한다. 뇌졸중 저위험군 심방세동 환자에게는 항응고 치료를 시행하지 않아도 된다. 항혈소판제는 뇌졸중 예방을 위한 항응고 치료로 추천되지 않는다. 출혈 위험도 역시 항응고 치료를 위해 고려해야 하며, 출혈 위험도를 항응고 치료 제외기준으로 사용해서는 안된다. 장기간 항응고요법을 안전하게 유지할 수 없는 환자의 경우 좌심방이 폐색술을 고려해 볼 수 있다. 결론적으로 심방세동 환자에서 바람직한 뇌졸중 예방 치료는 교정 가능한 출혈 위험을 주기적으로 확인하고 교정하여 출혈 위험은 최소화하면서 개별 환자의 특성을 종합하여 전신적인 항혈전 치료(경구 항응고제) 또는 국소적인 항혈전 치료(좌심방이 폐색술/배제술)를 적용하여 임상적인 순 이득을 최대화하기 위한 지속적이고 다학제적인 노력이다.

Acknowledgements

본 연구는 대한부정맥학회 및 보건복지부의 재원으로 환자중심 의료기술 최적화 연구사업의 지원을 받았다(과제고유번호: HC19C0130).