2021 대한부정맥학회 심방세동의 선별 검사 및 무증상 심방세동의 관리 지침

2021 Korean Heart Rhythm Society Guidelines for Screening and Management of Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation

Article information

Trans Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a strong risk factor for embolic stroke. In patients with AF, optimal anticoagulation therapy, administered according to the stroke risk scoring system, can effectively reduce the stroke risk. However, AF episodes are frequently asymptomatic, with a significant number of them detected after a stroke event. Therefore, the early detection of subclinical AF and the subsequent administration of optimal oral anticoagulation therapy is expected to reduce the risk of stroke. However, this strategy requires more effective screening for the detection of AF in the asymptomatic stage, which accounts for the recent research interest in silent/subclinical AF. Today, the widespread use of cardiac implantable electronic devices and wearable rhythm monitors has enabled the detection of atrial high-rate episodes/subclinical AF in a substantial number of patients. The risk of stroke appears to be related to the duration of this phenomenon. Subclinical AF increases the risk of stroke, but generally not as much as clinical AF, but whether long-term anticoagulation therapy is required in patients with subclinical AF is unclear. Here we review existing data on the epidemiology, clinical significance, and suggest guidelines on management of subclinical AF and the optimal screening strategies aimed at its detection.

서 론

심방세동은 뇌경색의 강한 위험 인자로써 심방세동이 진단되면 뇌경색 위험도에 따라 적절한 항응고 치료를 통해 뇌경색을 예방할 수 있다. 그러나 상당수의 심방세동은 무증상이며, 뇌경색이 발생한 후에 비로소 심방세동이 발견되는 경우가 많다. 따라서 무증상 심방세동에 대한 체계적인 선별 검사와 적절한 항응고 치료가 필요하다. 최근에는 다양한 웨어러블 모니터링 기기와 모바일 헬스 애플리케이션들이 개발되면서 심방세동의 진단율을 향상시킬 수 있을 것으로 기대되고 있으나, 임상적 검증 및 사용 지침의 정립이 필요하다. 무증상 심방세동은 뇌경색 위험도를 증가시키지만 심전도로 진단된 임상적 심방세동에 비해서는 위험도가 낮다. 뇌경색 위험도는 무증상 심방세동의 지속시간에 따라서 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있으나, 정확히 어떠한 기준으로 항응고 치료를 시작할 지에 대해서 현재까지 확립된 지침은 없다. 대한부정맥학회에서는 심방세동을 조기에 발견하기 위한 선별 검사 전략과 무증상 심방세동 환자에게 적절한 항응고 치료는 어떠한 것인지 현재까지 발표된 증거를 바탕으로 관리지침을 제시하고자 한다.

심방세동 환자의 선별 검사

선별 검사 방법들

심방세동의 진단을 비롯한 다양한 모바일 헬스 기술들은 빠르게 발전하고 있으며, 현재 100,000개 이상의 모바일 헬스애플리케이션과 400개 이상의 웨어러블 모니터링 기기들이 사용 가능하다[1]. 그러나 아직 충분한 임상적 검증이 이루어지지 않은 기기들이 많으므로 임상적 사용에는 주의가 필요하겠다. 스마트 워치를 이용한 심방세동 진단에 대한 연구들이 발표된 이후로 심방세동 위험도가 높은 환자군을 대상으로 한 심방세동의 선별 검사가 주요 관심사로 떠오르고 있다[2,3]. 최근에는 머신 러닝, 인공지능 등을 이용해 동율동 심전도만으로도 발작성 심방세동 환자를 감별하는 연구가 발표되어 심방세동 진단의 중대한 발견으로 여겨지고 있다[4].

Apple Heart 연구[5]는 스마트 워치 애플리케이션 사용자 419,297명(평균 40세)의 자원자를 대상으로 미국에서 시행되었으며, 이 중 0.5%의 사용자에서 불규칙한 맥박이 발견되었다(40세 미만 0.15%, 65세 이상 3.2%). 이 0.5%의 환자들을 대상으로 1주일간의 패치형 심전도 감시를 진행한 결과 34%에서 심방세동이 발견되었다. Huawei Heart 연구[6]는 187,912명(평균 35세, 86.7% 남성) 중 0.23%에서 ‘심방세동 의심’ 소견이 보고되었는데, 그중 적절히 추적 관찰이 이루어진 대상자들 중 87.0%가 심방세동으로 확진 되었고, 이러한 과정에서 광용적맥파(photoplethysmography, PPG) 신호의 양성예측도가 91.6% (95% 신뢰구간 91.5-91.8%)에 달하는 것으로 보고되었다. 또한 이 연구에서 심방세동으로 확진된 대상자의 95.1%가 모바일 심방세동 애플리케이션을 이용한 심방세동의 통합적 관리 프로그램에 참여하는 결과를 도출하였다.

심전도 기록이 가능한 웨어러블 디바이스(단일유도 심전도 기기 등)에서 30초 이상의 심방세동이 의사에 의해 확인된 경우, 심방세동의 확진이 가능하다. 심방세동의 발견이 심전도에 의한 것이 아닐 경우(예: PPG를 이용한 기기의 경우)나 심전도 측정기기에서 확보된 심전도 기록의 해석이 불분명할 경우에는 확진을 위해 추가적인 심전도 기록이 필요하다(예: 12-유도 심전도, 홀터 검사 등).

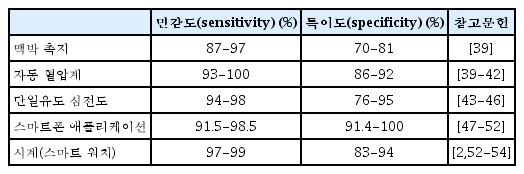

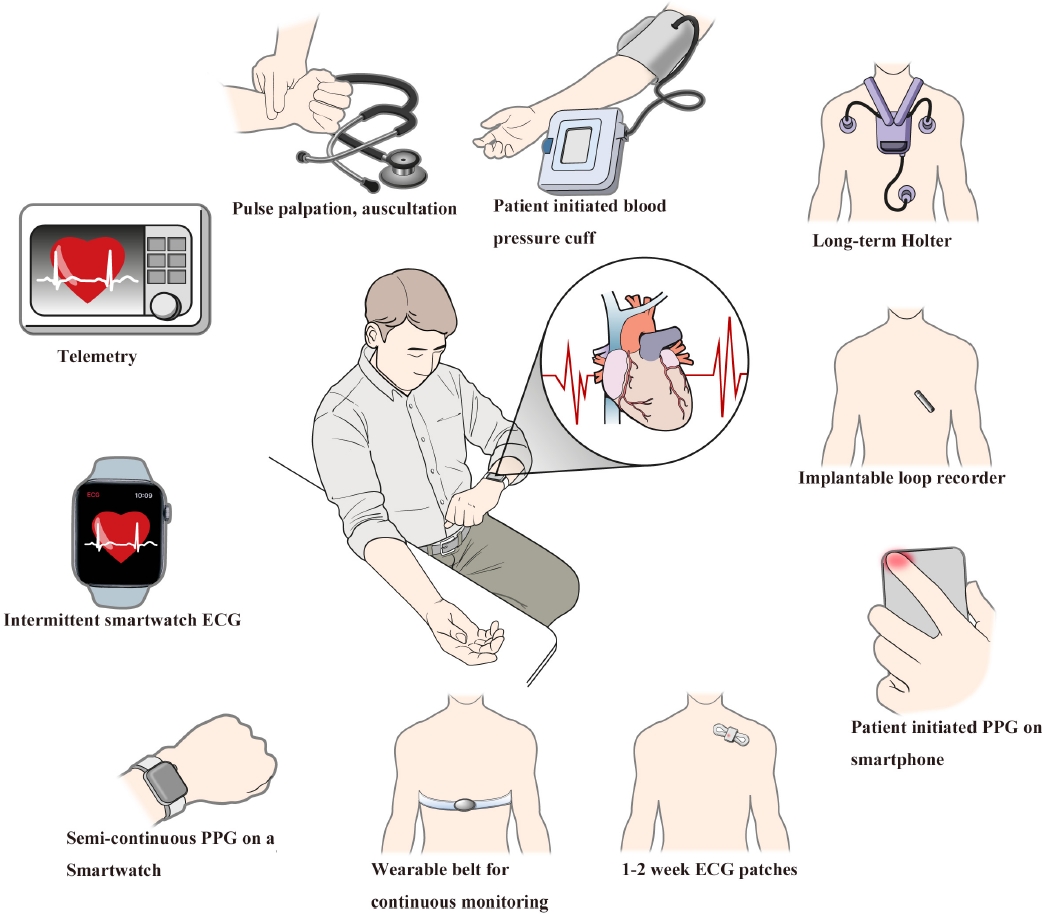

표 1에서 보고되는 민감도, 특이도 등의 수치들은 일반적으로 대부분의 연구들이 소규모의 관찰 연구에서 도출되었으며 신호의 선택에 있어 상당한 편향이 이루어졌을 가능성이 있기 때문에 해석에 신중해야 한다. 한편으로는 이미 상용화 되어 있는 기기들의 알고리즘이나 기술들 역시 지속적으로 발전하고 있기 때문에 이 역시 해석에 고려되어야 할 것이다. 최근에 발표된 2개의 메타분석 연구에서 단순 심전도만을 통한 심방세동 선별 검사는 맥박 촉지를 통한 선별 검사 대비 큰 진단율의 이득이 없다고 보고된 바 있다[7,8]. 심방세동 선별 검사에 사용되는 시스템들은 표 1 과 그림 1에 정리되어 있다.

선별 검사 방법과 전략

일반적으로 심방세동의 선별 검사에 주로 사용되는 방법으로는 기회적 선별 검사 그리고 조직적 선별 검사 방법이 있는데, 조직적 선별 검사는 주로 고령자(주로 65세 이상)를 대상으로 간헐적인 일정 시점 또는 반복적인 30초간의 심전도 기록을 2주간 반복하게 된다. 스마트폰이나 스마트 워치를 통한 모니터링을 얼마나 자주 하는 것이 적절한지에 대해서는 아직 정해진 바가 없다. 일차 의료기관, 약국 또는 특별한 행사 등을 통한 지역사회 선별 검사 등은 심방세동의 선별 검사의 좋은 예시이다[9,10]. 메타분석 연구들에서는 대체로 조직적 선별 검사와 기회적 선별 검사, 일반적 진료 시의 진단과 지역사회 선별 검사 간에 큰 차이는 보이지 않으나, 반복적인 검진이 일회성 검사보다는 확연히 나은 진단율을 보여주고 있다[7]. 선별 검사로 심방세동이 발견되었거나 의심되는 환자에 대한 의뢰를 통한 추가적 검사 진행까지의 체계가 잘 정립되는 것이 환자의 적절한 치료에 중요하다.

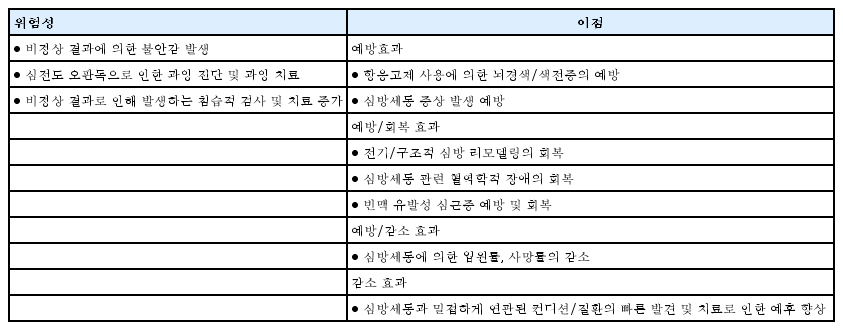

심방세동 선별 검사의 장점과 위험성

선별 검사를 통해 아직 진단되지 않은 심방세동을 진단할 때의 잠재적인 이점과 위험성은 표 2에 정리되어 있다[10]. 심방세동의 선별 검사는 진단은 이미 되었으나 충분히 관리받지 못하고 있던 심방세동 환자들을 재조명해주는 효과가 있다[11]. 간헐적인 심전도의 확인은 심방세동의 발견율을 4배 올리게 된다[11]. Remote HEArt Rhythm Sampling using the AliveCor heart monitor to screen for Atrial Fibrillation (REHEARSE-AF) 연구에서는 스마트폰이나 태블릿을 통해 단일유도 심전도를 1주일에 2회 측정하는 방식을 1년간 지속하였더니 65세 이상 환자군에서 대조군 대비 심방세동 발견율이 3.9배 증가하였다고 보고하였다[12]. 적절한 정보 제공 및 빠른 심전도 판독 결과를 제공하는 선별 검사 체계의 정립은 확진을 받지 못한 환자의 불안감을 적절히 감소시킬 수 있다. 그러나 선별 검사로 시행하는 심전도의 오판독으로 인한 과잉 진단 및 과잉 치료가 초래될 수 있는 가능성, 비정상 결과로 인한 환자의 불안감이나 침습적 검사의 증가 가능성 등, 선별 검사의 잠재적인 위험성에 대해서도 주의가 필요하다.

심방세동 선별 검사의 비용-효과

심방세동을 미처 진단 및 치료받지 못해 발생하는 의료 비용이 증가하므로 아직 진단되지 않은 심방세동 환자를 찾아 치료하는 것은 합당하다[13]. 심방세동에 대한 선별 검사는 조직적 선별 검사에 비교하여 기회적 선별 검사가 적은 비용이 든다[10]. 또한 심방세동을 선별하고자 할 때는 도구와 절차를 적절하게 선택하는 것이 중요하다[14]. 맥박 측정, 휴대용 심전도 측정 장치 그리고 스마트폰을 활용한 선별 검사가 비용면에서 효과적이었다[9]. 65세 이상의 경우 조직적 선별 검사와 기회적 선별 검사 모두 비용 대비 효과적이었으나 기회적 선별 검사가 더 비용 대비 효과적이었다[15].

고위험군에서의 선별 검사

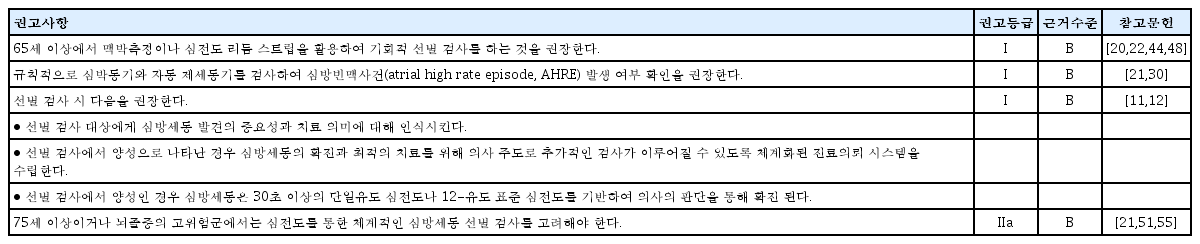

심방세동은 무증상일 수 있으며 뇌졸중 또한 고령일수록 발생 위험이 증가하므로 고령에서 심방세동을 선별 검사하는 것은 합당하다[16-18]. 65세 이상의 노인 인구 집단에서 기회적 선별 검사와 75세 및 76세에서 2주간의 휴대용 심전도 측정장치를 활용한 자가 측정은 비용 대비 효과적이었다[19,20]. 65세 이상에서 맥박 측정 후 심전도를 시행해 본 결과 심방세동의 유병률은 4.4%였으며 1.4%는 심방세동을 진단받지 않은 상태였다. 한 명의 심방세동 환자를 선별하기 위해 70명의 선별 검사가 필요하였다[21]. 뇌졸중의 위험인자가 2개 이상인 75-76세의 인구집단에서 2주간 휴대용 심전도 기록장치를 활용한 선별 검사에서는 7.4%에서 무증상의 심방세동이 확인되었다[22]. 따라서 65세 이상에서는 기회적 선별 검사를 추천하며, 75세 이상이거나 뇌졸중의 고위험군에서는 체계적인 심방세동 선별 검사를 고려해야 한다. 30초 이상의 단일유도 심전도나 12-유도 표준 심전도에서 심방세동이 발견되면 임상적 심방세동(clinical AF)을 확진할 수 있다. 심방세동 선별 검사에 대한 권고사항은 표 3에 정리되어 있다.

심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동(atrial high rate episode [AHRE]/subclinical AF)의 역학, 임상적 의미, 관리

심박동기를 가지고 있는 환자의 30-70%에서 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동이 발견되며, 일반인에서는 이보다는 더 낮을 것으로 예측된다[23]. 하루 10-20초 이하의 짧은 심방빈맥사건은 뇌경색이나 전신색전증의 위험을 높이지 않기 때문에 임상적으로 큰 의미가 없다고 간주된다[24]. 그러나 최소 5-6분 이상으로 지속되는 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동은 심방세동[25,26], 뇌경색[26,27], 주요심혈관사건[28], 심장 원인의 사망[29]과 연관성이 있다. 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동은 실제 임상적 심방세동보다는 뇌경색의 위험도가 낮다[26,27,30,31]. 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동의 발생 시간과 뇌경색의 발생이 시간적으로 별 연관이 없었으며, 따라서 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동은 뇌경색의 위험인자라기 보다는 연관된 표지자일 수 있다[32-34].

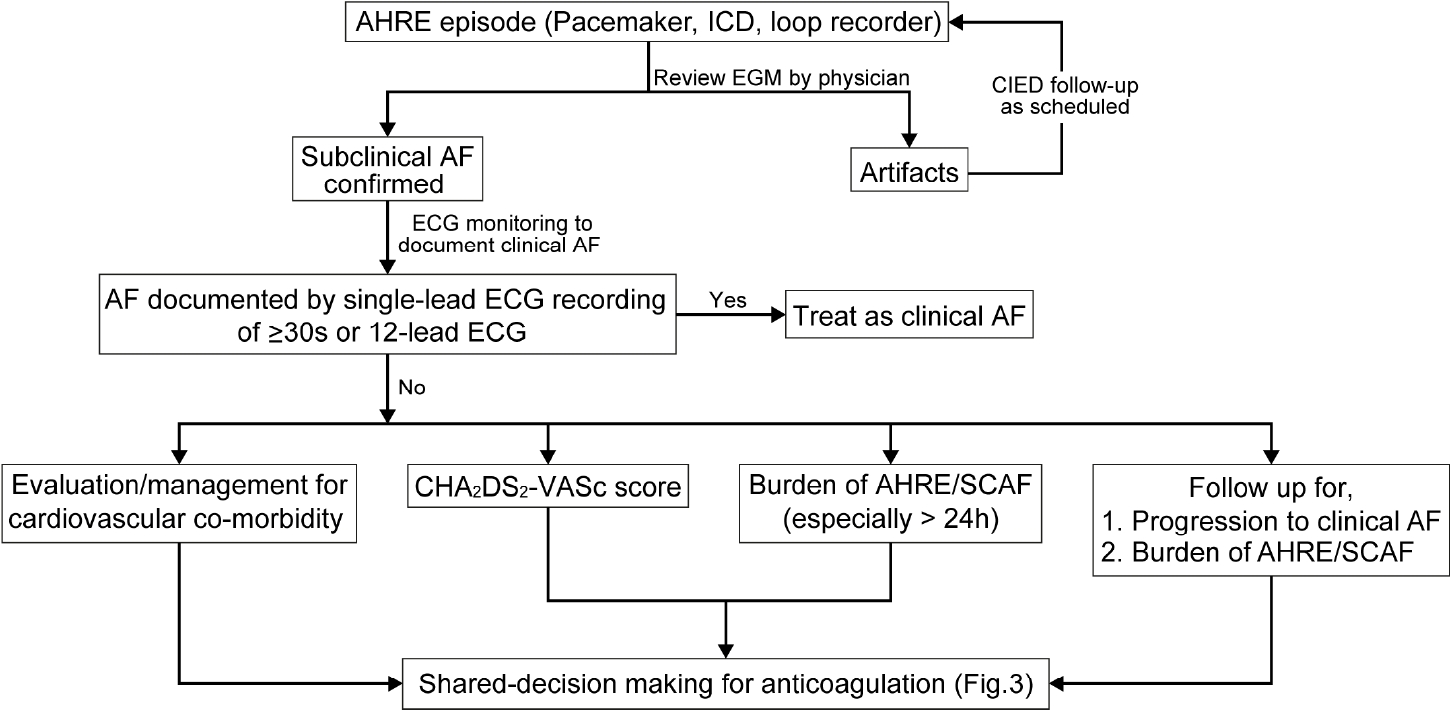

현재까지 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동에 관한 데이터는 대부분 심박동기/삽입형제세동기를 가지고 있는 환자나, 뇌경색 발생 이후의 환자들로부터 얻은 것이지만 최근에는 심전도 모니터링을 하는 다양한 환자군을 대상으로도 보고가 증가하고 있다. 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동이 발견된 환자 5-6명 중 1명은 2.5년 이내에 임상적 심방세동이 발견된다고 알려져 있다[27]. 따라서 이러한 환자들에서는 더 집중적인 추적 관찰(원격 모니터링 등)을 하는 것이 도움이 될 것이나, 어떠한 관리 방법이 최적인가에 대해서는 좀 더 연구가 필요하다. 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동의 양은 일정한 것이 아니라 매일 변동할 수 있기 때문에[25], 정기적인 재평가가 필요하다. 최초 진단 당시 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동의 양이 많은 환자일수록 추적 관찰에서 더 긴 심방빈맥사건이 발견될 확률이 높다[25]. 이전에 임상적 심방세동이 진단된 적이 없는 환자에서 심박동기/삽입형제세동기/삽입형루프기록기 등의 심장 내 전기장치로 발견된 무증상 심방빈맥사건에 대한 적절한 관리 방법은 그림 2에 나타내었다.

Management of atrial high-rate episodes/subclinical AF. AF, atrial fibrillation; AHRE, atrial high rate episode; EGM, electrogram; CIED, cardiac implantable electronic device; ECG, electrocardiography; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; SCAF, subclinical atrial fibrillation.

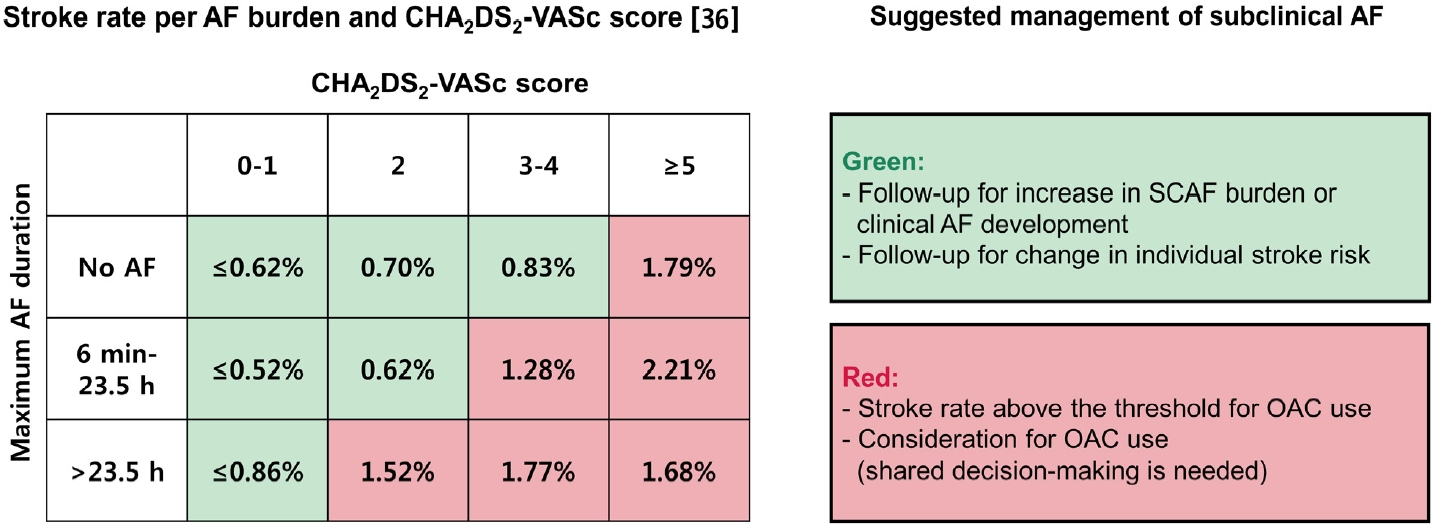

심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동 환자에서 일상적으로 경구항응고제를 사용해야 한다는 증거는 부족한 상황이나, 교정 가능한 뇌경색 위험인자는 꼭 찾아내고 관리해주어야 한다. 경구항응고제 사용을 고려하는 경우로는 오래 지속되는 심방 빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동(24시간 이상), 뇌경색의 위험인자가 높은 환자에서는 순임상적이익과 환자선호도를 고려하여 선택적으로 사용할 수 있다(Fig. 3) [33-35]. 최근 연구들에서는 뇌경색의 위험인자가 2개 이상이고 삽입형루프기록기에서 6분 이상의 심방세동이 의사에게 확진된 경우, 각각 환자의 56%, 76%에서 경구항응고제를 시작했다고 보고하였으나, 출혈사건 발생률 등은 보고하지 않았다[36,37]. 원격 모니터링 데이터를 분석한 대규모 후향 코호트 연구에서는, 경구항응고제 시작에 관하여 의사들마다 진료 패턴이 다양함을 보고하였다. 항응고제 치료를 받지 않는 환자에서 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동의 양이 증가함에 따라 뇌경색의 위험도도 증가하였으며, 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동이 24시간 이상인 환자들에서는 경구항응고제 사용이 뇌경색의 위험도 감소와 유의한 연관성이 있었다[38]. 심방빈맥사건/무증상 심방세동 관리에 관한 권고사항은 표 4에 정리되어 있다.

Risk of stroke according to the AF burden and CHA2DS2-VASc score (left), and the suggested management of subclinical AF (right). AF, atrial fibrillation; OAC, oral anticoagulation; SCAF, subclinical atrial fibrillation.

결 론

무증상 심방세동의 조기 진단을 위해 65세 이상에서 맥박 측정이나 심전도 리듬 스트립을 활용하여 기회적 선별 검사를 하는 것을 권장한다. 75세 이상이거나 뇌졸중의 고위험군에서는 심전도를 통한 체계적인 심방세동 선별 검사를 고려해야한다. 무증상 심방세동이 발견된 환자에서는 심전도, 뇌경색의 위험인자, 동반 질환 평가 등을 비롯하여 심혈관계의 면밀한 평가를 하도록 권장한다. 무증상 심방세동이 발견된 환자는 정기적으로 추적 관찰하여 임상적 심방세동으로 진행 여부, 무증상 심방세동의 양 변화(특히 24시간 이상으로 증가하는지) 및 기저 질환의 변화를 평가해야 한다. 무증상 심방세동에서 항응고 치료의 시작 여부는 무증상 심방세동의 지속 시간, CHA2DS2-VASc score를 고려하여 결정한다. 심방세동의 지속시간이 길고 CHA2DS2-VASc score가 높은 경우, 항응고 치료가 임상적으로 이득이 될 것으로 생각되나 대규모 무작위 대조 연구가 필요하다.

Acknowledgements

본 연구는 대한부정맥학회 및 보건복지부의 재원으로 환자 중심 의료기술 최적화 연구사업(과제고유번호: HC19C0130)과 범부처전주기의료기기연구개발사업(과제고유번호: 202013B14) 의 지원을 받았다.

The authors thank Medical Illustration & Design, part of the Medical Research Support Services of Yonsei University College of Medicine, for all artistic support related to this work. Dr. Choi has received research grants from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Biosense Webster, Chong Kun Dang, Daiichi-Sankyo, Samjinpharm, Sanofi-Aventis, Seers Technology, Skylabs, and Yuhan. No fees are directly received personally.