FODMAP이란?

What is the FODMAP?

Article information

서 론

기능성 위장관 질환은 기질적인 원인 없이 복통 등의 증상의 악화와 호전이 반복되는 질환으로 과민성장증후군이 대표적인 예이다. 아직까지 원인과 치료법이 다양하고, 증상의 호전을 위한 노력은 꾸준히 계속되어 왔다. 최근 증상과 관련된 식이와 증상호전을 위한 음식의 선택에 대한 관심은 점점 더 증가하고[1], 증상의 유발과 호전에 관계된 다양한 음식에 대한 연구가 전 세계적으로 진행되고 있으나 각 나라의 식이습관이 다양하여 국내에서 쉽게 적용하기에는 어려운 실정이다.

Fermentable, Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides and Polyols(FODMAPs)에 대한 연구는 1991년 호주 멜버른의 Monash 대학의 소화기 내과의사 Gibson 박사와 당시 같은 대학에 근무하던 영양학자 Shepherd 박사에 의해서 연구가 시작된 이후로 저FODMAP식이(low FODMAP diet)에 대한 지속적인 연구 덕분에 현재는 FODMAPs의 섭취와 관련한 병태생리기전이 밝혀지고, 이중맹검 무작위 교차실험의 연구성과를 발표하고, 꾸준히 환자-의사-식이전문가 단체 교육의 성과를 내고 있다[2].

본 논문에서는 FODMAPs의 정의, 전반적 특성, 병태생리, 구성, 다양한 연구성과, 장기처방의 문제점에 대하여 알아보고, 나아가 저FODMAP식이의 국내적용의 가능성과 제한점에 대하여 살펴보고자 한다.

본 론

FODMAPs?

FODMAPs는 Fermentable, Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides and Polyols의 첫 글자의 약자로, 장내에서 발효되기 쉬운 올리고당(oligosaccharides), 이당류(disaccharides), 단당류(monosaccharides), 그리고 폴리올(polyol)을 뜻하는 약자이다. 언급된 짧은 사슬 탄수화물은 사람의 장내에서는 쉽게 흡수되지 않아서 삼투압을 증가시키는 역할을 하지만 장내세균에 의해서 쉽게 분해되어 가스를 발생시키는 성질을 가지고 있다.

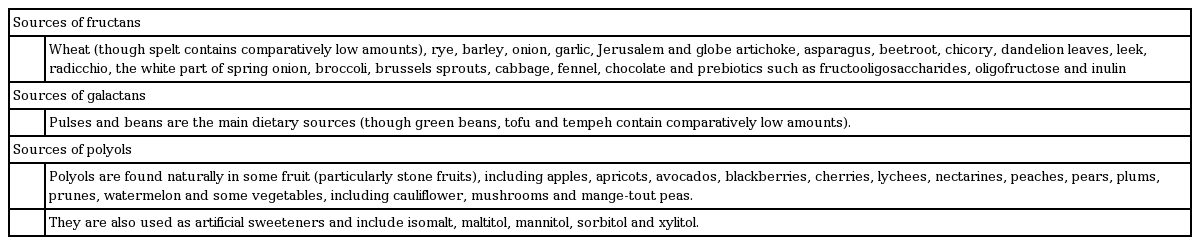

올리고당류는 포도당(glucose), 과당(fructose), 갈락토스(galactose)와 같은 단당이 3-10개 정도 결합한 짧은 형태의 당으로 설탕 단맛의 20-40% 정도를 내지만, 실제로 소장의 소화효소에 의해서 분해되지 않으므로 인체에서 거의 흡수되지 않아 다이어트 식품으로도 자주 이용된다. 올리고당에는 프룩탄(fructan)과 갈락탄(galactan)이 포함되며, 프룩탄은 다수의 과당이 포함되어 있어서 fructo-oligosaccharides라고도 하고, 갈락탄은 다수의 갈락토스가 포함되어 galacto-oligosaccharides라고도 하는 짧은 사슬 탄수화물이다. 이들은 많은 종류의 식물(Table 1), 예를 들면 양파, 콩, 파, 아리초(artichoke), 아스파라거스, 병아리콩, 돼지감자 등에 다량 포함되어 있다. 이러한 자연에 포함된 올리고당 이외에도 전분을 세균 또는 효소로 분해하여 짧은 사슬 탄수화물로 만든 합성 올리고당인 말토덱스트란(maltodextrans)과 셀로덱스트란(cellodextrans)이 있다[3].

이당류는 두 개의 단당류가 결합된 형태로 존재하며, 락토오스(lactose), 말토오스(maltose), 슈크로스(sucrose) 등이 해당된다. 락토오스(젖당)는 포도당과 갈락토스, 슈크로스(설탕)는 포도당과 과당, 말토오스(맥아당)는 포도당과 포도당이 결합하고 있다. 이들은 가수분해에 의해서 단당류로 분해될 수 있다. 주로 우유, 요거트, 아이스크림, 커스터드 크림, 치즈 등에 흔히 존재한다[3].

단당류는 탄수화물의 가장 기본적인 단위로 당분의 가장 단순한 형태이다. 대표적으로 포도당, 과당, 갈락토스가 있으며, 주로 과당이 FODMAPs에 해당한다. 사과, 포도, 수박, 서양배, 감, 코코아, 인스턴트 커피, 양파, 마늘가루, 꿀에 많이 존재한다[3].

폴리올은 다수의 알코올기를 가지는 합성당이며, 소르비톨(sorbitol), 만니톨(mannitol), 자일리톨(xylitol), 말타톨(maltitol)이 포함되며, 주로 식품감미료에 많이 포함되어 단맛을 낸다(Table 1). 다수의 탄산음료와 과일쥬스, 사탕, 껌, 합성 감미료 등에 포함되어 있다[3].

FODMAPs의 병태 생리

FODMAPs의 병태 생리는 첫째, FODMAPs에 해당하는 짧은 사슬 탄수화물이 소장에서 거의 흡수되지 않거나 매우 천천히 흡수된다는 점이다. 소장에서 흡수되는 정도는 사람마다 다양한 차이를 보이며, 락토오스 분해효소를 가지고 있지 않은 경우는 분해되지 않은 lactose가 모두 대장으로 이동한다. Polyol의 경우는 개인적인 차이가 심하게 나타나는 당류이다[4,5].

둘째, FODMAPs은 적은 양이면서도 삼투압에 의한 수분량 변화를 유발하기에 충분하다는 것이다. 그러므로 우리 몸에서는 이러한 FODMAPs을 희석시킬 목적으로, 장관내 수분 분비가 증가하고 장관 내 수분흡수가 감소되어 장관 내 수분량이 증가하고 위장관 운동이 빨라져 설사를 유발한다. 또한, 빠르게 발효되는 탄수화물은 장내의 삼투압을 높인다. 한 연구에서 슈크로스, 폴리올 등이 포함된 용액을 섭취하면 장내 수분이 2배 이상 증가하고 이로 인하여 분변의 무게가 증가하였다[6]. 정상인에서도 17.5 g의 만니톨 용액을 섭취하였을 때 같은 정도의 포도당을 섭취하였을 때보다 40분 후에 소장의 수분이 10배 증가하였다[7].

셋째, FODMAPs은 대장에 살고 있는 장내세균에게는 매우 이용하기 좋은 물질로, FODMAPs의 섭취가 증가할수록 이를 이용하는 장내세균의 발효작용이 증가하고 결과적으로 가스(수소, 메탄, 이산화탄소)가 발생하게 된다. 이렇게 증가한 가스는 복통, 복부 팽만감, 더부룩증(bloating)을 유발한다. 호기 검사를 통해 수소와 메탄을 측정하여 대장 내 발효 가스를 측정할 수 있으며, 발효가능한 탄수화물의 투여 후 약 0-5시간 사이에 정상인과 과민성장증후군이 있는 환자군 모두에서 가스형성이 증가하였고, 교차투여 실험에서도 기준식이를 하였을 때에 비해 다양한 짧은 사슬 탄수화물을 투여하였을 때 급격히 수소가스가 정상인과 환자군 모두에서 증가하였고, 프룩탄의 섭취 후 더 많은 양의 수소가 발생하고, 조기에 감소하였다[8].

넷째, 올리고당은 소화되어 흡수되지는 않지만 장내세균이 충분히 이용 가능한 에너지원이 되어 프리바이오틱스(prebiotics)로 작용할 수 있다. 실제로 3주 동안 FODMAPs의 섭취를 줄인 경우, 전체적인 장내세균의 양은 감소하였지만 장내에 유익한 부틸레이트(butylate)를 생산하는 Clostridium cluster XIVa와 점막에 유용한 Akkermansia muciniphila는 증가하였고, 점막에 좋지 못한 Ruminococcus torques는 감소하였다[4].

정상인의 경우, FODMAPs에 의해서 발생한 장내 수분증가와 가스 발생으로 인한 증상은 거의 발생하지 않는 반면, 기능성 위장관 질환 특히 과민성장증후군 환자의 경우는 내장 과민성(visceral hypersensitivity)이나 뇌-장축(brain-gut axis)에 문제가 있는 경우가 흔하므로, 이렇게 발생한 가스와 수분에 의해 충분히 증상이 유발된다(Fig. 1) [2,5,9-17]. 또한 장기간 FODMAPs 섭취를 제한한 경우, 증상이 있는 환자에서 다양한 이로운 효과가 있었다[4].

저FODMAP식이의 구성

실제 임상에서 식단표와 식이를 결정하기 위해 단순히 피해야 할 음식이나 권해야 할 음식으로 구분하여 교육하는 것은 부적절하며, 식이 전문가의 도움을 받는 것이 필요하다. 식이의 구성 중 평소 식사량을 유지하는 것은 중요하며, 식사량의 감소는 오히려 식이 조절이 필요한 대상환자의 의지를 감소시킬 수 있다. 또한 장기간 저FODMAP식이를 위해서는 충분한 칼로리를 제공해야 하고 균형 잡힌 식단이 필요하다. 식단에는 다섯 가지 식품군(유제품, 육류과 육가공품, 과일, 채소, 곡물)이 모두 충분히 제공되어야 한다. 기본적인 개념은 식사량과 열량을 그대로 유지하면서 FODMAPs이 많이 포함된 식재료를 FODMAPs이 적게 포함된 것으로 대처한다는 것이다[18,19].

성공적인 치료를 위해서는 대상환자에게 기능성 질환에 대한 개념과 식이의 중요성을 인식시키고, 저FODMAP식이의 개념과 식이 방법, 식단의 결정, 요리방법의 선정 등을 잘 이해할 수 있도록 지속적인 교육이 필수적이다. 이를 위해서는 환자-의사-식이전문가의 상호작용이 중요하며, 환자의 교육에는 개인별 치료도 효과가 있지만 의사-식이전문가-환자집단과 같은 그룹교육도 개인별 치료만큼이나 효과 있다[20]. 지속적인 증상호전을 위해서는 환자에게 식이전문가가 작성한 처방식이 식단으로 2-6주간 시행하고, 환자를 재교육 후 환자로 하여금 식단을 작성하도록 하고 식단의 문제점을 피드백해 주어야 하며, 환자가 저FODMAPs식이에 대하여 완전히 이해하고 일상생활에 잘 적응할 수 있을 때까지 근접 모니터링을 해주는 것이 필요하다. 식이 전문가의 역할은 섭취해야 할 식품과 회피해야 할 식품에 대한 교육뿐만 아니라 식단으로 정한 음식에서 FODMAPs을 제거하고 좀 더 맛있게 만드는 방법을 가르치고, 나아가서는 환자가 식품구성표를 보고 새로운 식단을 개발할 수 있는 정도까지 발전시켜 성공적인 치료를 보장할 수 있도록 도움을 주는 것이다.

식단의 결정이나 음료수의 선택에 있어서 음식에 포함된 FODMAPs의 정도에 대한 지식은 매우 중요하다. 인터넷과 책자를 통해 제공된 자료는 불완전하고 정확하지 않은 경우도 있으며, 일상생활에서 간편하게 확인할 수 없다. FODMAPs에 대한 가장 활발한 연구가 이루어지고 있는 호주의 Monash 대학에서는 스마트폰용 어플리케이션[21]과 책자[22]를 통하여 정보를 제공하고 있어 쉽게 확인이 가능하고 유용하게 이용할 수 있다(Fig. 2).

저FODMAP식이의 임상적 유용성

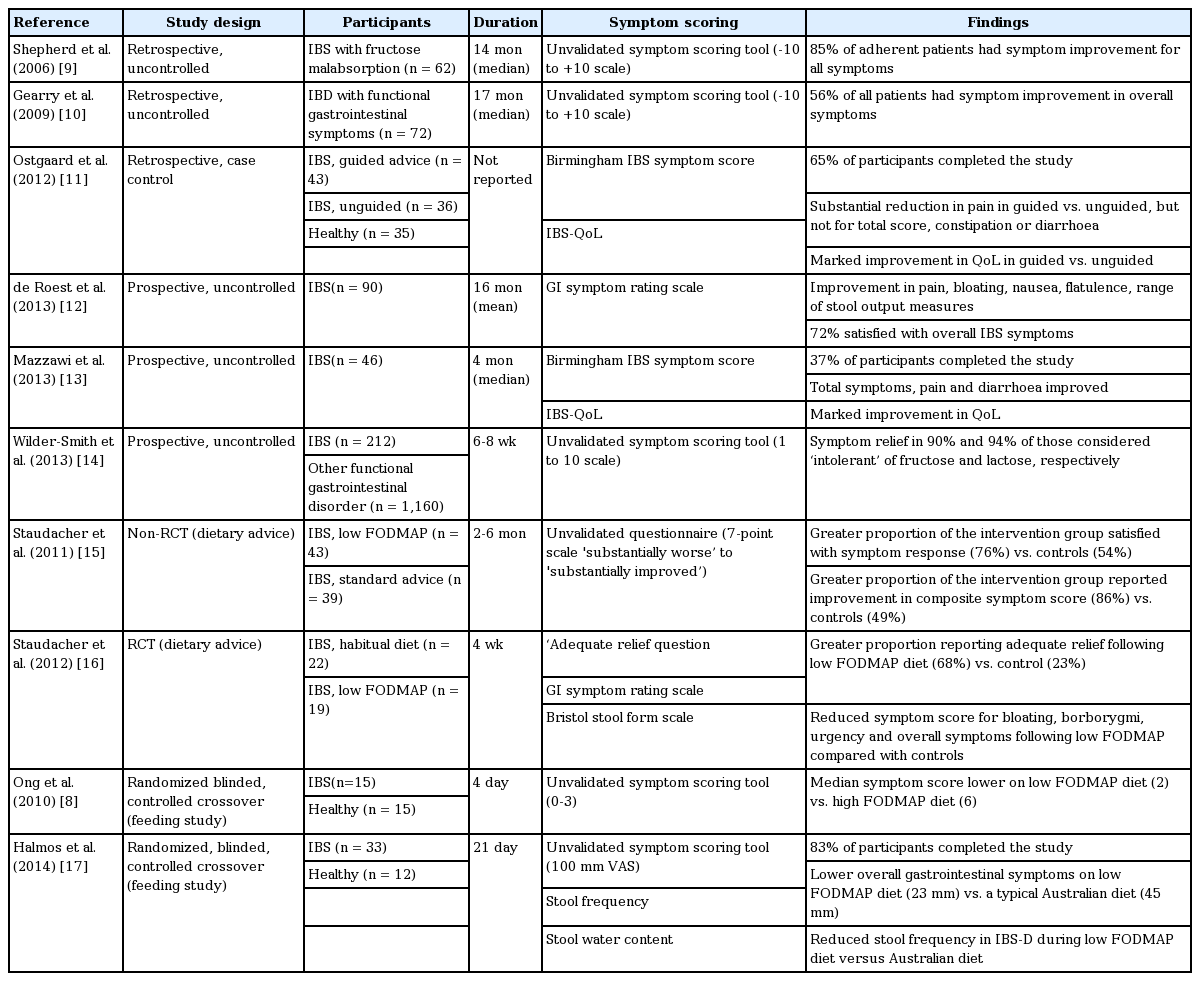

지난 10년간의 연구를 살펴보면, 주된 대상은 과민성장증후군이며, 식이전문가의 도움을 받아 표준화된 식단을 작성하고 대조군과 환자군에서 증상의 변화를 확인하는 연구에서 시작하여, 점차로 무작위 이중맹검 교차실험으로 발전하였다(Table 2). 지역도 호주에서 시작하여 뉴질랜드, 북미로 전파된 이후 서유럽과 북유럽의 여러 나라에서도 참여하고 있다. 최근에는 동아시아지역에서도 연구가 시작되고 있고, 우리나라에서도 많은 관심을 가지고 연구를 준비하고 있다.

표준화 연구[17]에서 정상인과 과민성장증후군 환자를 대상으로 21일 동안 저FODMAP식이/전형적인 오스트레일리아식 음식을 제공 후 교차실험을 시행하여 각각의 식이에 따른 증상의 변화를 비교하였으며, 정상인에서는 어떠한 종류의 식사에도 증상 변화가 없었으나, 과민성장증후군 환자에서는 저FODMAP식이 후 증상이 확연히 호전됨을 확인하였다(Fig. 3).

종합하면, 저FODMAP식이와 연관된 대부분의 연구들에서 70% 이상의 과민성장증후군 환자가 식이의 변화로 증상의 호전을 경험하였다(Table 2). 전반적인 증상의 호전은 저FODMAP식이를 시작하고 7일 이내에 시작되었고, 호전된 증상은 저FODMAP식이를 지속하는 동안 잘 유지되었으며, 일부에서는 연구기간 이후에도 상당 기간 동안 지속되었다[12-17]. 증상 호전의 이유는 앞서 병태생리에서 설명된 내용과 동일하다. 연구 기간 동안 중대한 부작용은 발생하지 않았다.

이와 같은 연구 결과를 바탕으로 저FODMAP식이를 과민성장증후군 환자의 일차치료로 적용해야 한다고 주장하는 학자들이 늘어나고 있다. 많은 연구가 진행되었지만 아직까지 정확한 비교연구가 부족하고, 연구의 대부분이 임상적 접근이 아닌 새로운 식이를 시도하는 연구이므로 실제임상 적용과는 차이가 있을 수 있고, 장기간 연구 자료가 부족하고, 소아 또는 염증성장질환 등의 다른 질환에도 적용 가능한지 등의 문제점이 있다.

한국에서의 저FODMAP식이

한국에서의 FODMAPs에 대한 연구는 아직 활발하지 않다. 그 이유로는 첫째, 아직 우리나라에서는 식품, 식자재에 포함되어 있는 FODMAPs의 성분표시가 의무화되어 있지 않아 FODMAPs의 포함 정도를 확인하기 어렵다. 외국 연구에서 도움을 받을 수 있으나 각 나라별 선호하는 식품에 차이가 있고, 같은 식품에서도 나라마다 함유량이 달라 외국의 자료를 인용하는 데에는 제한점이 있다. 둘째, 질환에 대한 인식의 차이가 있다. 우리나라에서의 전통적인 과민성장증후군의 치료는 환자의 증상 호전과 삶의 질 향상에 초점이 맞추어져 있고, 약제의 처방이 주된 역할로 인식되어 있다. 식이/음식은 의사의 영역과 차이가 있다고 생각하는 경향이 있어, 이에 대한 인식의 변화가 시급하다. 셋째, 다학제 치료에 대한 경험의 부족과 지원체계의 부재가 문제가 될 수 있다. 저FODMAP식이는 환자-식이전문가-의사가 다학제적 접근이 필요한 부분이지만 이에 대한 경험과 지원이 부족하다. 하지만 많은 의사들이 점차 이에 대한 필요성과 중요성을 인식하고 있고, 학회와 심포지엄을 통해 중요성을 강조하고 있다.

서양에서는 저FODMAP식이의 조리법과 식단이 이미 잘 정리되어 있지만, 우리나라에서는 아직 마련되지 않았다. 한국 먹거리의 중요한 부분인 김치의 경우, 재료인 배추 이외에 부재료로 분류되는 마늘, 무, 파, 고추, 첨가제 등이 모두 FODMAPs의 함량이 높다. 또한 김치 이외에 된장, 고추장, 쌈장 등도 콩의 함량이 높아 모두 FODMAPs의 함량이 높은 음식으로 분류된다. 만두나 딤섬의 경우도 만두소에 들어 있는 양파, 파, 양배추, 마늘 등에 FODMAPs의 함량이 높다. 카레의 경우에도 양파, 마늘, 버섯, 양배추 등으로 인하여 FODMAPs이 높은 음식으로 분류된다. 중국 음식에서도 사용하는 버섯, 양배추, 마늘, 콩으로 만든 춘장, 꿀, 각종 소스 등에 FODMAPs의 함량이 높으나, 쌀국수, 면요리, 중국빵 등에는 FODMAPs의 함량이 낮다. 이와 같이 우리나라에서 흔히 먹는 다수의 음식에서 FODMAPs가 많이 포함되어 있어 식단과 조리법에 대한 연구는 반드시 필요하다.

결 론

FODMAPs은 장관내 수분 증가(과당, 폴리올)와 장내 가스 발생 증가(과당, 갈락탄)로 인하여 과민성장증후군과 같은 기능성 위장관 질환의 증상을 유발하거나 악화시킬 수 있다. 다양한 연구에서 저FODMAP식이는 과민성장증후군의 증상(복통, 복부팽만감, 복부가스)을 전반적으로(> 70%) 호전시켰다. 성공적인 저FODMAP식이를 위해서는 환자-식이전문가-의사의 다학제적 접근법이 필요하다. 한국의 김치, 된장, 고추장, 쌈장 등은 FODMAPs의 함유량이 높아서 한국의 과민성장증후군 환자에서 저FODMAP식이는 효과가 있을 것으로 판단되며, 이에 대한 더 많은 연구가 필요하다.