비결핵 항산균 폐질환의 진단과 치료

Diagnosis and Treatment of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease

Article information

Trans Abstract

The incidence of chronic pulmonary disease caused by nontuberculus mycobacteria (NTM) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patients has been increasing worldwide. In Korea, the common etiologic pathogens for this disease are Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium abscessus. Most NTM pulmonary diseases present one of two forms such as fibrocavitary or nodular bronchiectatic disease according to their radiographic features. However they also present hypersensitivity like diseases and solitary pulmonary nodules. NTM pulmonary disease has specific diagnostic criteria including repeated isolations of organisms because they are ubiquitous environmental organisms and NTM isolation can be a result of specimen contamination. However diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease does not mean the need for immediate treatment. Also since it needs multiple antibiotics for a long time, treatment is expensive and has significant side effects. Therefore treating NTM lung diseases can be extremely difficult and factors such as patient’s age, comorbid conditions, and progression rates of symptoms and disease should be considered in the decision of treatment. (Korean J Med 2012;82:274-283)

서 론

결핵과 나병과 유사한 미생물이 자연환경에 널리 존재한다는 것은 1800년 후반부터 알려지게 되었다. 이런 미생물을"atypical", "anonymous", "mycobacteria other than tuberculosis", "environmental", "environmental opportunistic" 등과 같이 여러가지 용어로 사용하였고 비결핵 항산균(nontuberculous mycobacteria, NTM)을 가장 많이 사용하고 있다[1].

NTM은 폐질환, 림프절염, 피부 질환, 파종성 질환 등을일으키고 이 중 폐질환은 NTM에 의한 질환 중 90% 이상을 차지한다[1,2]. NTM 폐질환은 공기를 통한 균의 흡인으로발생하는 것으로 생각되며 결핵과는 달리 NTM은 동물에서 사람으로 또는 사람 간에 전염을 시키지 않는 것으로 알려져 있어 감염된 환자라도 격리가 필요하지 않다[3]. 최근 많은 산업화된 국가들에서 결핵 유병률의 감소와 함께 NTM 폐질환의 증가로 NTM 폐질환이 폐결핵보다 더 높은 유병률을 보이고 있다[4]. 최근 국내에서도 임상 검체에서 NTM의 분리 비율과 NTM 폐질환의 진단 및 치료가 증가하고 있다[5-8]. 따라서 일선 임상의사들의 NTM 폐질환에 대한 관심이 증가할 것으로 추측할 수 있다. 본 종설에서는 최근 증가하는 NTM 폐질환의 임상양상과 치료에 대해서 2007년 개정된 미국흉부학회와 미국감염학회의 진료지침[2]을 중심으로 살펴보고자 한다.

역 학

우리나라에서 NTM 폐질환은 1981년 Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) 폐질환 1예[9]를 보고한 것을 처음으로 최근에 급격한 증가를 보이고 있다. NTM 폐질환의 증가는 실제 최근 환자의 증가일 수도 있으나 항산균 연구의 기술적 발전과 NTM 폐질환에 대한 의료진의 인식의 증가도 한 원인이 될 수 있다. 그러나 전염성 질병이 아닌 NTM 폐질환은 발생률과 유병률 파악이 힘들다. 국내에서는 일부 병원에서 임상 검체의 항산균 배양 중 NTM이 20-30%까지 보고하고 있어 적지 않은 비율로 분리되고 있음을 알 수 있다[10,11].

NTM 폐질환을 일으키는 원인균은 국가에 따라 그리고 국가 내에서도 지역에 따라 다양한 분포를 보이고 있다. 미국과 일본에서는 MAC이 가장 흔하며, Mycobacterium kansasii (M. kansasii)가 두 번째로 흔한 원인균이고, 영국에서는 지역마다 달라서 England와 Wales에서는 M. kansasii가 가장 흔하고, Scotland에서는 M. malmoense가 가장 흔하며, England의 동남부에서는 M. xenopi가 가장 흔하다[2,12-14]. 우리나라에서는 MAC이 50% 이상 차지하여 가장 흔하고 다른 나라와 달리 M. abscessus가 두 번째로 흔하며 미국과 일본에서 두 번째로 흔한 M. kansasii는 드물게 발견되는 것으로 되어 있으나 대부분의 국내연구들이 일부 지역의 단일 기관의 연구이며 검체 및 대상 환자 수가 많지 않아 정확한 빈도는 불확실하다[8,11,15].

검사실 검사법

NTM의 진단에 미생물학적 진단기준이 중요하고 원인균의 동정은 치료에 중요하기 때문에 NTM 감염에서 검사실 검사법은 매우 중요하다. 결핵의 진단을 위한 항산균 도말 및 배양 검사를 NTM에서도 동일하게 사용할 수 있다.

검체를 받을 경우 NTM은 수돗물을 포함한 주변 환경에 존재하기 때문에 이곳으로부터 오염되는 것에 주의해야 한다. Macrolide와 quinolone는 임상에서 많이 사용하는 항생제로 NTM 분리에 영향을 줄 수 있어 NTM 감염이 의심되는 환자에서 가능한 항생제 사용은 자제하는 것이 좋다.

항산균 도말 검사는 일반적인 결핵에서 사용하는 방법과 동일하며 도말 검사로는 결핵균과 NTM이 구별되지 않는다. 따라서 국내에서도 NTM 분리 비율이 증가하고 있어 항산균 도말 검사 양성인 경우 NTM 감염도 고려해야 한다. NTM 배양은 결핵과 동일하며 고체배지인 Ogawa와 Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube 960 (MGIT, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA)과 같은 액체배지(broth media)를 사용한다. 배양 양성률을 높이기 위해 두 배지에서 모두 배양할 것을 권유하고 있다. 특히 고체배지와 비교하여 액체배지에서 NTM 배양 양성이 크게 높은 것으로 알려져 있다[16]. 고체배지는 NTM의 배양 모양과 성장 속도 및 배양 정도의 정량 검사가 가능하고 액체배지가 오염된 경우 대체할 수 있는 장점이 있다[2].

배양된 NTM은 결핵균과 구별 후 NTM의 세부 균 종까지 구별이 필요하다. M. avium과 M. Intracellulare는 임상적 차이가 아직 밝혀지지 않아 구별이 필요하지 않으나 가능한 모든 균에서 세부 균 종의 구별이 필요하며 특히 rapidly grwoing micobacteria (RGM)에서는 M. Chelonae/abscessus group과 같이 군으로 구별하는 것은 권하지 않으며 DNA sequencing 또는 PCR restriction endonuclease assay와 같은 적절한 방법으로 세부 균 종의 구별을 권유하고 있다. 따라서 분리된 NTM의 동정 검사의 범위와 분리된 균의 중요성을 결정하기 위해 임상의사와 진단검사의사와의 소통이 필요하다[2].

결핵 치료 중 NTM이 배양된 경우 이에 대한 임상적 중요성에 대해 고민을 할 수 있다. 이에 대한 연구는 드물고 국내에서 시행한 한 연구에서 958명의 배양양성 결핵 환자 치료 중 NTM 배양은 전체 배양된 결핵의 7% 정도이고 2%만이 2회 이상 NTM이 배양되었으며 단 2명(0.2%)만 결핵 치료 중 M. abscessus가 지속 배양되어, 임상적으로 의미 있는 NTM 폐질환이 있는 것으로 확인되었다[17]. 따라서 결핵 치료 중 배양되는 NTM균은 임상적 의미가 크지 않을 것으로 추정된다.

동일한 환자에서 서로 다른 NTM균이 배양되는 경우에 대한 임상적 해석 또한 어렵다. M. abscessus 폐질환에서 MAC가 동정될 수 있고 결절 기관지확장증형 MAC에서도 M. abscessus가 동정될 수 있다[18,19]. 최근에 시행된 국내 연구에서는 NTM 폐질환 환자의 28%에서 동일한 환자에서 서로 다른 종류의 NTM이 동정되어 적지 않은 수에서 서로 다른 균이 동정될 수 있음을 보였다[20]. 그러나 이에 대한 임상적 의미에 대해서는 불확실하다.

결핵과는 다르게 NTM 감염에서 약제 내성 검사가 임상적 의미를 가지는지에 대해서는 논란이 많다. MAC 감염에서 macrolide 내성 여부는 치료 반응과 관계가 있어 초치료 또는 재치료 MAC 감염에서 clarithromycin 내성 검사를 권유하고 있다[2]. Azithromycin은 clarithromycin과 교차 내성이 있어 감수성 검사를 추가로 할 필요는 없다. 국내에서 두 번째로 흔한 M. abscessus 경우 amikacin, doxycycline, imipenem, quinolones, sulfonamide, cefoxitin, clarithromycin에 대한 약제 감수성 검사를 권유하고 있으나 이에 대한 임상적 중요성에 대한 연구는 거의 없다. 국내에서 시행한 한 연구에서 M. abscessus에서 clarithromycin 내성이 확인된 경우 치료 실패가 많은 것으로 보고하였다[21]. M. kansasii 내성 검사는 치료실패와 연관성이 있는 rifampin에 대해서만 필요하다. 치료 중 isoniazid와 ethambutol에 획득 내성이 있을 수 있으나 이는 주로 rifampin 내성과 관련이 있다[22]. 따라서 과거 치료한 적이 없는 M. kansasii 감염의 경우는 rifampin 내성 검사만 권유하고 rifampin 내성이 보고된 경우는 rifabutin, ethambutol, isoniazid, clarithromycin, fluoroquinolones, amikacin, sulfonamide와 같은 2차 약에 대한 내성 검사를 권유한다[2].

국내에서는 결핵연구원에서 NTM의 여러 균 종에 대한 약제 감수성 검사를 시행하고 있고 이를 이용할 수 있다.

임상적 특징

NTM 폐질환은 특징적인 증상이 없다. 대부분의 환자들이 만성 재발성 기침을 하며 객담, 피로와 권태감, 호흡곤란, 열, 객혈, 흉통, 체중감소 등의 증상을 호소할 수 있다. 증상은 보통 질병이 진행하면서 심해지지만 기관지확장증, 만성폐쇄성폐질환, 낭성섬유증, 진폐증 등과 같은 동반된 다른 폐질환에 영향을 많이 받는다. 신체 검사에서 나타나는 소견 또한 대부분 비특이적이다[2].

전세계적으로 NTM 폐질환의 가장 흔한 원인균인 MAC 폐질환은 “상엽 공동형(upper lobe cavitary form)”과 “결절 기관지확장증형(nodular bronchiectatic form)”의 두 가지 서로 다른 임상상을 가지고 있다[2,23] (Fig. 1). 상엽 공동형은 오래 전부터 잘 알려진 질환으로 주로 40대에서 50대의 중년남성에서 오랜 기간의 흡연력과 음주력이 있는 경우에 잘 발생하고 대부분 만성폐쇄성폐질환과 기존의 폐결핵 등 기저 질환을 가지고 있다. 흉부방사선촬영에서는 폐결핵과 유사한 상엽의 공동과 섬유화를 보이는 병변이 관찰된다. 그러나 폐결핵과의 차이는 폐실질에 둘러싸인 얇은 벽을 가진 공동과 기관지를 통한 병변의 전파보다는 접촉성 전파가 더 뚜렷하고 흉막을 더 현저히 침범하는 특징을 가지고 있다. 이러한 형태의 MAC 폐질환은 치료를 하지 않으면 1-2년 이내에 광범위한 폐 실질의 파괴와 호흡부전으로 사망에 이르게 된다[2,23].

Different forms of Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Nodular bronchiectatic forms in 56 years old woman with Mycobacterium avium infection (A, C). Chest radiograph shows a multiple patchy distribution of small nodules in both lungs with right predominance (A). Chest CT scan shows small centrilobular nodules and bronchiectasis in the both lungs (C). Chest radiograph and CT scan of upper lobe cavitary forms in 55 years old man with Mycobacterium intracellulare infection show thin-walled cavity in the left upper lobe (B, D).

MAC 폐질환의 두 번째 형태인 결절 기관지확장증형은 1980년대 후반에서야 알려진 질병으로 기저 질환이 없는 중년 이상의 비흡연자 여성에서 주로 발견되어 “Lady Windermere syndrome”으로 불려지기도 한다[24]. 이 질환은 특징적인 고해상도 전산화단층촬영 소견을 가지는데 중심부에 다발성 기관지 확장증과 주변의 작은 결절과 침윤이 주로 우중엽과 좌상엽의 설상엽에서 관찰된다. 이러한 방사선학적 병변은 병리학적으로 기관지주위의 광범위한 육아종성 병변을 나타내는 것으로 MAC가 집락균으로 존재하는 것이 아니라 폐조직을 침범하였다는 것을 의미한다[25-27]. 결절 기관지확장증형의 MAC 폐질환은 상엽 공동형 MAC 폐질환에 비해 진행속도가 매우 느려서, 장기간의 추적 관찰이 필요하다[2].

M. abscessus는 외국에서는 드문 원인균으로 M. abscessus 폐질환은 중년 이상의 비흡연자 여성에서 흔히 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다. 이전의 마이코박테리아 감염, 낭포섬유화증, 만성적인 구토를 동반한 위식도 질환 등의 동반 질환을 가진 환자가 40% 정도에서 관찰되고 기저 질환을 가지고 있지 않은 경우에는 병의 진행이 매우 느려, 증상발생부터 진단까지 평균 2년 이상이 소요된다[18]. M. abscessus 폐질환의 전산화단층촬영 소견은 MAC 폐질환과 유사하게 상엽 공동형과 결절 기관지확장증형이 관찰되고 있다[28-30].

NTM 폐질환은 위의 특징적 임상상 이외에 과민성 폐렴과 유사한 형태로도 나타날 수 있다. NTM이 오염된 온수욕조에 노출되어 발생한 경우가 보고되어 hot tub lung이라고도 불리고 있고 온수욕조 이외에 직업적 노출에서도 발생할 수 있다[2,31]. 또한 NTM 폐질환은 고립성 폐결절 형태로 나타날 수 있다[32-34] (Fig. 2). 결핵과 NTM에 의해 발생하는 육아종은 구별이 힘들기 때문에 고립성 폐결절의 조직 검사에서 육아종이 보이는 경우 NTM 폐질환의 가능성 또한 생각해야 하며 NTM에 의한 고립성 폐결절은 대부분은 MAC에 의한 감염으로 알려져 있다[32,33].

Atypical forms of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Contrast-enhanced chest CT scan of 45-year-old woman with Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease shows a solitary pulmonary nodule in the right upper lobe which contains the necrotic low-attenuation portions and tiny calcifications within the nodule (A). Chest CT scan of 54 years old man with hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to Mycobacterium terrae shows diffuse patchy and geographic area of ground-glass attenuation and air-trapping and mixed, ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass attenuated nodules (B) [31].

진 단

NTM은 자연환경에 널리 분포하고 있어 객담과 기관지세척액 등의 호흡기 검체에서 NTM이 분리되었다고 해서 이것이 NTM 폐질환의 증거라고 할 수 없다. 따라서 진단을 위한 특별한 기준이 필요하다. 미국흉부학회와 감염학회(American Thoracic Society and Infectious Disease Society of America) [2]에서 제시한 진단기준을 요약하면, 임상적으로 첫째, 호흡기 증상이 있고 흉부방사선촬영에서 결절과 공동 또는 흉부전산화단층촬영에서 다발성 기관지확장증과 다발성 소결절이 있고 둘째, 다른 질환이 배제되어야 한다. 미생물학적으로는 첫째, 적어도 2개 이상의 별도의 객담에서 NTM이 배양되거나 둘째, 적어도 1개 이상의 기관지세척액 또는 기관지폐포세척액에서 NTM이 배양되거나 셋째, 기관지 폐생검 또는 기타 폐조직 검사에서 육아종성 염증이나 항산균 도말 양성 등의 병리학적 증거가 있으면서 조직배양에서 NTM이 확인되거나 1회 이상의 객담 또는 기관지 세척액에서 NTM이 배양되어야 한다(Table 1). 최근의 진단기준은 1997년 미국흉부학회의 진단기준[23]보다 미생물학적 진단기준에서 상당히 완화된 것으로 2007년 개정된 진단기준을 사용한 경우 1997년 진단기준을 사용한 경우에 비해 NTM 폐질환의 진단율이 높고 더 빠른 진단을 할 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[35]. 그러나 위 진단기준은 잘 알려진 병원균인 MAC, M. kansasii, M. abscessus에 적합하게 만들어졌으며 기타 흔하지 않은 균이 동정된 경우는 위 진단기준이 적절하지 않을 수 있다. 병원성이 낮은 M. fortuitum이나 오염균일 가능성이 높은 M. gordonae, M. terrae 등이 동정된 경우는 오랜 시간을 두고 반복적인 배양 검사가 필요하며 원인균으로 판정하는 데는 주의가 필요하며 전문가의 자문을 구하는 것이 좋다. NTM 폐질환의 진단기준의 제한점과 NTM 폐질환이 대부분 느리게 진행하는 것을 고려하고 불필요한 치료를 막기 위해서는 진단 및 원인균을 판정하기 위해서 오랜 시간의 충분한 추적 관찰과 충분한 검체를 통한 미생물학적 진단이 필요하다.

치 료

NTM 폐질환의 치료에서 가장 힘든 것 중 하나는 언제 치료를 시작해야 하는가일 것이다. 미국흉부학회의 가이드라인에서 제시하듯이 NTM 폐질환의 진단이 즉각적인 치료를 의미하는 것은 아니다. NTM 치료는 장기간의 항생제 치료가 필요하기 때문에 부작용과 얻을 수 있는 이득을 고려해서 신중히 결정해야 한다. 또한 결절 기관지확장증형 MAC와 M. abscessus 폐질환은 오랜 기간을 두고 서서히 진행하는 질병으로 경우에 따라서 오랜 기간 동안 병의 악화가 없을 수 있다[2,36,37]. 따라서 전문가들은 증상과 영상 소견상 폐 손상이 심하지 않는 경우는 일정기간 증상과 영상의 변화를 관찰 후 치료를 결정할 것을 권유하고 있다[36-38]. 치료시작에는 환자의 연령과 동반 질환들 또한 고려해야 한다.

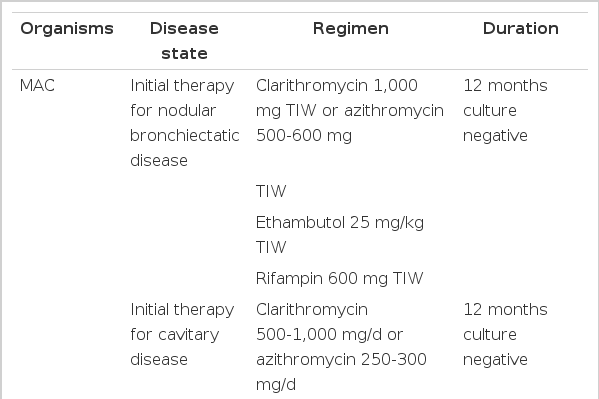

NTM의 치료는 MAC의 경우 clarithromycin, azithromycin 등 macrolide 계열의 항생제가 가장 중요하며, clarithromycin 시험관내 감수성 결과와 임상경과의 관련성이 높다. 1997년 미국흉부학회는 MAC 폐질환의 치료에 clarithromycin (1,000 mg) 또는 azithromycin (250 mg), rifampin (600 mg) 또는 rifabutin (300 mg) 그리고 ethambutol (초기 2개월은 25 mg/kg, 이후 15 mg/kg) 등 최소한 세 가지 약제를 매일 병합 투여하고 객담 도말 양성 또는 공동을 동반하는 등 진행된 폐질환을 가진 환자는 초기 2개월 동안 streptomycin 근육주사를 고려하도록 하였다[23]. 2007년 미국흉부학회와 감염학회에서 발표한 새로운 진료지침에서는 환자의 개별 상태에 따라 치료약제 선택을 달리 할 것을 권장하였다[2]. 결절 기관지확장증형의 대부분의 환자에서는 (1) clarithromycin 1,000 mg 혹은 azithromycin 500-600 mg, (2) ethambutol 25 mg/kg, (3) rifampin 600 mg을 1주일에 3회 투여하는 간헐치료를 하고 섬유공동형 또는 심한 결절 기관지확장증형의 환자는 (1) clarithromycin 1,000 mg 1일 1회(또는 500 mg 1일 2회) 혹은 azithromycin 250 mg, (2) ethambutol 15 mg/kg, (3) rifampin 10 mg/kg (최대 600 mg)을 매일 투여한다. 심하고 광범위한 병변을 가진 환자 그리고 재치료 환자는 초기 2-3개월간 amikacin 혹은 streptomycin 주사제 투여를 고려한다(Table 2). 공동이 없는 대부분의 결절 기관지확장증형의 MAC 폐질환에서 주 3회 항생제를 투여하는 간헐치료를 권장하는 이유는 치료효과는 유지하면서 부작용은 감소시킬 수 있기 때문이다[39]. MAC 치료의 가장 중요한 macrolide의 경우 최근 국내에서도 clarithromycin과 azithromycin 모두 보험급여가 인정되어 사용할 수 있다. 그러나 이둘 중 어떤 약이 치료효과와 내성 발생에 더 우월한지에 대한 비교 임상연구는 없다. MAC 치료에 가장 많이 사용하는 clarithromycin은 소화기계 부작용과 간독성 등으로 고령의 환자들에게 장기간 사용하는 것이 쉽지 않다. 따라서 미국흉부학회와 감염학회의 지침은 고령 또는 체중이 적은 환자에게는 500 mg으로 감량을 고려할 수 있다고 하였다. 하지만 clarithromycin 용량을 일일 500 mg으로 낮추어 투여해도 일일 1,000 mg 투여하는 것과 치료효율이 같은지는 불확실하며, 최근의 국내외 보고는 낮은 용량에서 치료효율이 떨어질 가능성을 시사하고 있다[40-42]. Rifamycin 중 rifampin과 rifabutin 중 어떤 약이 MAC 폐질환에 더 효과적인가에 대해서는 알려진 바가 없다. 단지 rifabutin에 의한 부작용이 빈발하여 전문가들은 rifampin을 추천하고 국내에서는 rifabutin은 보험급여가 인정되지 않고 있다[2]. Ethambutol에 의한 시신경염은 장기간의 사용이 필요한 MAC 폐질환치료에서 결핵치료보다 더 많이 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있고 간헐치료보다는 매일 치료에서 더 많이 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다[43]. Aminoglycoside 주사 치료는 광범위한 MAC 폐질환의 치료 초기 사용을 권유하고 있다. 일본에서 시행한 비교 임상실험에서는 치료약제에 streptomycin이 포함된 환자들에서 객담배양 음전율이 높았다[44]. Amikacin과 streptomycin 중 어떤 약이 더 우월한지는 알려져 있지 않고 하루 여러 번 정맥 주사가 필요한 amikacin보다는 하루 한 번의 근육주사가 가능한 streptomycin을 더 많이 사용하고 있다. MAC 폐질환의 치료에는 여러 가지 항생제의 장기간 사용이 필요하여 많은 부작용이 발생할 수 있다. 이런 부작용으로 치료한 환자들의 20% 정도가 치료를 견디지 못하고 투약 중단하는 것으로 알려져 있다[45]. 따라서 MAC 폐질환의 치료에서 부작용 발생의 주의 깊은 관찰과 이에 대한 적절한 조치는 중요할 것으로 생각된다.

MAC 치료 성적은 새로운 macrolide의 도입으로 성공률이 크게 증가하였으나 이에 대한 연구가 많지 않고 대부분의 연구들에서 대상 환자 수가 적으며, 치료에 사용된 약의 종류 또한 다양하고, 치료 성공률에 포함한 대상 환자군 또한 다양해서 치료 성공률의 차이가 크고 해석에 주의가 필요하다. Field 등[45]이 1990년 이후 12개 임상연구들에서 치료 시작한 모든 환자들을 대상 환자로 분석했는데 치료 성공률이 56% 정도였다. 최근 국내에서 미국 흉부학회와 감염학회의 진료지침에 따른 표준치료의 성공률에 대한 연구가 2개 발표되었고 macrolide 포함한 표준 치료법으로 균 음전율이 80% 가까이 높게 보고되어 표준 치료법이 MAC 폐질환에 효과적이라고 보고하였다[38,40]. 그러나 이 연구들은 후향적 연구이고 치료 중인 환자들이 포함되어 있으며 치료 종료 후 충분한 추적기간이 없어 재발 환자들에 대한 분석이 불충분한 단점이 있다.

MAC 폐질환에서 치료 성공에 영향을 주는 인자에 관해서는 macrolide 내성, 과거 6개월 이상의 치료력, 치료시작 시 도말 양성인 경우, 공동이 있는 경우 등이다[38-40,45,46]. 공동이 치료에 영향을 주는지에 대해서 상반된 결과를 보이지만 macorolide 내성과 과거 6개월 이상의 치료력이 있는 환자는 치료가 매우 어려운 것으로 보고되고 있다. Griffith 등[46]이 macrolide 내성 MAC 폐질환 환자 51명의 치료에 대한 연구 결과를 보면 경구용 약으로 치료 한 경우는 37명 중에서는 불과 2명(5%)만이 균음전에 성공할 정도로 치료 성공률이 낮았다.

M. abscessus는 일반적인 항결핵제뿐만 아니라 많은 항생제에 내성을 보인다. M. abscessus는 약제감수성 검사에서 clarithromycin, amikacin, cefoxitin 등에 대해서만 감수성을 보이고 미국흉부학회와 미국감염학회는 clarithromycin 혹은 azithromycin을 amikacin, cefoxitin, imipenem 등의 주사 항생제와 함께 사용할 것을 권장하고 있다(Table 2). 또한 감수성검사 결과가 다양하기 때문에 진단된 환자에서 모두 약제감수성 검사를 시행을 권유하고 있다[2]. 새로운 macrolide인 clarithromycin과 azithromycin은 M. abscessus에 효과가 있는 거의 유일한 경구용 항생제로 최근 연구에서 macrolide 내성 M. abscessus에서 치료실패가 높은 것으로 나타났다[21]. Amikacin은 가장 효과적인 주사 항생제이고 치료 초기에는 고용량의 cefoxitin과 함께 사용하도록 권유하고 있다. Cefoxitin의 부작용이 발생한 경우 등으로 사용할 수 없는 경우에는 imipenem으로 대체할 수 있다. 주사 항생제의 사용기간에 대해서는 1997년 진료지침에서는 2-4주, 2007년 진료지침에서는 2-4개월을 추천하고 있으나 근거가 부족하다[2,23]. 진료지침에 따른 M. abscessus 치료 효과에 대한 임상연구는 거의 없다. 최근 국내에서 시행된 연구에서 진료지침에 다른 치료를 한 경우 58%에서 균음전을 보였으나 주사 항생제 치료를 위해 장기간의 입원이 필요하고 부작용으로 중성구 감소증과 혈소판 감소증이 각각 51%와 3%에서 발생하였고 간독성이 15%에서 발생하여 치료가 쉽지 않음을 알 수 있다[21]. 따라서 M. abscessus 폐질환의 경우 주사용 항생제를 포함한 내과적 치료만으로는 객담 균음전을 이루기는 매우 어려워 병변이 국한된 경우는 폐절제술을 적극적으로 고려해야 한다. M. abscessus는 M. abscessus, M. massiliense 그리고 M. bolletii라는 세 가지 다른 균으로 이루어져 있다는 것이 최근 밝혀졌다[47,48]. 각 균 종의 분포는 나라에 따라 다르며, 국내에서는 M. abscessus와 M. massiliense이 각각 50% 내외를 차지하며 M. bolletii는 매우 드물다[49]. M. abscessus는 clarithromycin에 노출되면, erm 유전자가 발현되어 clarithromycin에 대한 유도내성이 발현된다[50]. 따라서 약제감수성 검사에서 clarithromycin 감수성을 보이더라도 실제 환자에게 투여하면 효과가 소실될 수 있다. 이와 달리 M. massiliense는 이러한 clarithromycin 유도내성이 발견되지 않아, 항생제 치료 성적이 M. abscessus에 비해 매우 높다고 최근 보고되었다[51]. 외국에 비해 국내에서 상대적으로 흔히 발생하는 M. abscessus와 M. massiliense 폐질환의 적절한 항생제 치료에 대해서는 향후 지속적인 연구가 필요하다.

M. kansasii 폐질환은 미국과 일본에서는 MAC에 이어 두 번째로 흔한 균이지만 우리나라에서는 상대적으로 드문 균이다. 임상 증상과 영상 소견이 결핵과 유사하다. 치료는 rifampin이 사용 가능하면서 성공률이 급증하여 치료 후 4개월째 균음전율이 100%에 달하고 치료 후 재발도 거의 없는 것으로 알려져 있다. 치료는 isoniazid (300 mg), rifampin (600 mg, 체중 50 kg 이하는 450 mg), ethambutol (15 mg/kg) 매일 투약을 권유하고 치료 기간은 균음전 이후 12개월 동안 유지할 것을 권유한다(Table 2).

결 론

NTM은 자연환경에 널리 분포하여 일상생활에 노출이 자연스럽게 일어나지만 NTM 폐질환은 일부의 환자들에서 발생하고 진행이 느려 과거 결핵의 유병률이 높은 때는 질병에 대한 관심이 높지 않았다. 최근 결핵의 유병률이 낮아지고 NTM 폐질환의 유병률이 높아지면서 임상의사의 관심이 높아지고 있다. 그러나 NTM 폐질환에 진단 및 치료에 대해서는 아직 제한점이 많아 진료지침을 따르더라도 적절한 임상의사의 판단이 필요할 때가 많다. 진단과 원인균이 불확실 한 경우는 이를 정확히 하기 위해 충분한 시간을 두고 미생물학적 검사가 필요하다. 또한 NTM 폐질환의 진단이 곧 치료를 의미하는 것이 아니고 질병의 악화 속도 환자의 연령과 기저 질환, 장기간의 항생제 사용에 따른 부작용 등을 고려하여 치료를 결정해야 한다. 치료를 시작한 경우는 치료 효과 확인과 더불어 부작용 발생의 주의 깊은 관찰 및 치료가 필요하다.